Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 36, Issue 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provider Directory Directorio De Proveedores Simply Healthcare Plans, Inc

Provider Directory Directorio de proveedores Simply Healthcare Plans, Inc. Florida Statewide Medicaid Managed Care Long-Term Care Program Gulf Coast Region Hardee, Highlands, Hillsborough, Manatee, Pasco, Pinellas and Polk Counties 1-877-440-3738 (TTY 711) www.simplyhealthcareplans.com/medicaid SFL-PD-0021-19 Simply Healthcare Plans, Inc. Provider Directory Directorio de proveedores Florida Statewide Medicaid Managed Care Long-Term Care Program Gulf Coast Region Hardee, Highlands, Hillsborough, Manatee, Pasco, Pinellas and Polk Counties 1-877-440-3738 (TTY 711) www.simplyhealthcareplans.com/medicaid SFL-PD-0021-19 Florida Statewide Medicaid Managed Care Long-Term Care Provider Directory / Cuidado a largo plazo de Medicaid Managed Care del Estado de Florida Table of Contents / Tabla de Contenido PAGE Important Information about Your Simply Health Plan/Información importante sobre su plan de salud de Simply ..................................................................................................... 1 Symbols Index/Índice de símbolos .................................................................................... 2 Description of Long-term Care services/Descripción de servicios de cuidado a largo plazo .................................................................................................................................. 6 Long Term Care Providers / Proveedores de cuidado a largo plazo ................................. 9 Transportation services/Servicios de transporte ............................................................. -

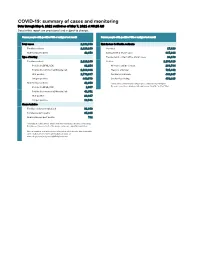

COVID-19: Summary of Cases and Monitoring Data Through Mar 23, 2021 Verified As of Mar 24, 2021 at 09:25 AM Data in This Report Are Provisional and Subject to Change

COVID-19: summary of cases and monitoring Data through Mar 23, 2021 verified as of Mar 24, 2021 at 09:25 AM Data in this report are provisional and subject to change. Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Total cases 2,021,656 Risk factors for Florida residents 1,984,274 Florida residents 1,984,274 Traveled 15,761 Non-Florida residents 37,382 Contact with a known case 778,821 Type of testing Traveled and contact with a known case 21,455 Florida residents 1,984,274 Neither 1,168,237 Positive by BPHL/CDC 72,860 No travel and no contact 234,183 Positive by commercial/hospital lab 1,911,414 Travel is unknown 671,148 PCR positive 1,602,679 Contact is unknown 438,609 Antigen positive 381,595 Contact is pending 429,882 Non-Florida residents 37,382 Travel can be unknown and contact can be unknown or pending for Positive by BPHL/CDC 890 the same case, these numbers will sum to more than the "neither" total. Positive by commercial/hospital lab 36,492 PCR positive 25,681 Antigen positive 11,701 Characteristics Florida residents hospitalized 84,006 Florida resident deaths 32,850 Non-Florida resident deaths 630 Hospitalized counts include anyone who was hospitalized at some point during their illness. It does not reflect the number of people currently hospitalized. More information on deaths identified through death certificate data is available on the National Center for Health Statistics website at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/COVID19/index.htm. -

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities Alaska Aialik Bay Alaska Highway Alcan Highway Anchorage Arctic Auk Lake Cape Prince of Wales Castle Rock Chilkoot Pass Columbia Glacier Cook Inlet Copper River Cordova Curry Dawson Denali Denali National Park Eagle Fairbanks Five Finger Rapids Gastineau Channel Glacier Bay Glenn Highway Haines Harding Gateway Homer Hoonah Hurricane Gulch Inland Passage Inside Passage Isabel Pass Juneau Katmai National Monument Kenai Kenai Lake Kenai Peninsula Kenai River Kechikan Ketchikan Creek Kodiak Kodiak Island Kotzebue Lake Atlin Lake Bennett Latouche Lynn Canal Matanuska Valley McKinley Park Mendenhall Glacier Miles Canyon Montgomery Mount Blackburn Mount Dewey Mount McKinley Mount McKinley Park Mount O’Neal Mount Sanford Muir Glacier Nome North Slope Noyes Island Nushagak Opelika Palmer Petersburg Pribilof Island Resurrection Bay Richardson Highway Rocy Point St. Michael Sawtooth Mountain Sentinal Island Seward Sitka Sitka National Park Skagway Southeastern Alaska Stikine Rier Sulzer Summit Swift Current Taku Glacier Taku Inlet Taku Lodge Tanana Tanana River Tok Tunnel Mountain Valdez White Pass Whitehorse Wrangell Wrangell Narrow Yukon Yukon River General Views—no specific location Alabama Albany Albertville Alexander City Andalusia Anniston Ashford Athens Attalla Auburn Batesville Bessemer Birmingham Blue Lake Blue Springs Boaz Bobler’s Creek Boyles Brewton Bridgeport Camden Camp Hill Camp Rucker Carbon Hill Castleberry Centerville Centre Chapman Chattahoochee Valley Cheaha State Park Choctaw County -

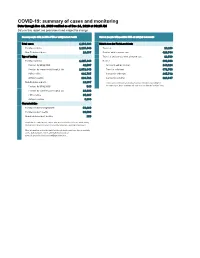

COVID-19: Summary of Cases and Monitoring Data Through May 6, 2021 Verified As of May 7, 2021 at 09:25 AM Data in This Report Are Provisional and Subject to Change

COVID-19: summary of cases and monitoring Data through May 6, 2021 verified as of May 7, 2021 at 09:25 AM Data in this report are provisional and subject to change. Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Total cases 2,262,598 Risk factors for Florida residents 2,220,240 Florida residents 2,220,240 Traveled 17,829 Non-Florida residents 42,358 Contact with a known case 887,914 Type of testing Traveled and contact with a known case 24,179 Florida residents 2,220,240 Neither 1,290,318 Positive by BPHL/CDC 81,254 No travel and no contact 268,784 Positive by commercial/hospital lab 2,138,986 Travel is unknown 725,442 PCR positive 1,770,667 Contact is unknown 493,047 Antigen positive 449,573 Contact is pending 459,315 Non-Florida residents 42,358 Travel can be unknown and contact can be unknown or pending for Positive by BPHL/CDC 1,007 the same case, these numbers will sum to more than the "neither" total. Positive by commercial/hospital lab 41,351 PCR positive 28,817 Antigen positive 13,541 Characteristics Florida residents hospitalized 91,848 Florida resident deaths 35,635 Non-Florida resident deaths 711 Hospitalized counts include anyone who was hospitalized at some point during their illness. It does not reflect the number of people currently hospitalized. More information on deaths identified through death certificate data is available on the National Center for Health Statistics website at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/COVID19/index.htm. -

COVID-19: Summary of Cases and Monitoring Data Through Dec 13, 2020 Verified As of Dec 14, 2020 at 09:25 AM Data in This Report Are Provisional and Subject to Change

COVID-19: summary of cases and monitoring Data through Dec 13, 2020 verified as of Dec 14, 2020 at 09:25 AM Data in this report are provisional and subject to change. Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Total cases 1,134,383 Risk factors for Florida residents 1,115,446 Florida residents 1,115,446 Traveled 10,103 Non-Florida residents 18,937 Contact with a known case 426,744 Type of testing Traveled and contact with a known case 12,593 Florida residents 1,115,446 Neither 666,006 Positive by BPHL/CDC 42,597 No travel and no contact 140,324 Positive by commercial/hospital lab 1,072,849 Travel is unknown 371,766 PCR positive 991,735 Contact is unknown 265,742 Antigen positive 123,711 Contact is pending 224,647 Non-Florida residents 18,937 Travel can be unknown and contact can be unknown or pending for Positive by BPHL/CDC 545 the same case, these numbers will sum to more than the "neither" total. Positive by commercial/hospital lab 18,392 PCR positive 15,107 Antigen positive 3,830 Characteristics Florida residents hospitalized 58,269 Florida resident deaths 20,003 Non-Florida resident deaths 268 Hospitalized counts include anyone who was hospitalized at some point during their illness. It does not reflect the number of people currently hospitalized. More information on deaths identified through death certificate data is available on the National Center for Health Statistics website at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/COVID19/index.htm. -

The Paisley Directory and General Advertiser

H to FOUNDED BY SIR PETER COATS, I87O. REFERENCE DEPARTMENT P.C. xa^^o No Book to be taken out of the Room. ^i -^A 2 347137 21 Digitized by the Internet Arciiive in 2010 witin funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/paisleydirecto189900unse THE . PAISLEY DIRECTORY AKD GENERAL ADVERTISER FOR 1899-1900. INCLUDING COMPREHENSIVE AND ACCURATE DIRECTORD S RENFREV\^ BLACKSTON, en JOHNSTONE, CLIPPENS, QUARRELTON, LINWOOD, ELDERSLIE, HOWWOOD, m INKERMANN, KILBARCHAN, Etc., >- WITH AN APPENDIX, m Comprising a Copious List of the Public Boards, Institutions, Societies, connected with the various localities. < a. -,.. r PAISLEY : J. & J, COOK, "GAZETTE" BUILDINGS, 94 HIGH STREET. MDCCCXCIX. FC/S30 THE HOLM LAUNDRY, ]P -A. I S X. E "2^ (Telephone 288). THE NEWEST AND BEST IN TOWN. GRASS PARK FOR BLEACHING. FIRST-CLASS CARPET BEATER. G-OODS COIiIiUCTED and DEIiIVERED FREE. GARDNER & CO. Nothing makes HOME so CLEAN, BRIGHT, and ATTRACTIVE as a liberal use of R 1 S©np Powder. Sole Makers : ISPALE & M'CALLUM, PAISLEY. WILLIAM CURRIE, JVIONUMENTAL SeULPiTOR, BROOWILANDS STREET, PAISLEY (OPPOSITE CEMETERY GATE). MONUMENTS, in Granite, Marble, and Freestone executed to any design. MONUMENTS AND HEADSTONES CLEANED AND REPAIRED. INSCRIPTIONS CUT IN EVERY STYLE. JOBBINGS IN TOWN and COUNTRY PUNCTUALLY ATTENDED TO. DESIGNS AND ESTIMATES FREE ON APPLICATION. PREFACE. The Publishers have pleasure ia issuing the present Directory, and hope that it will be found full and accurate. After the General and Trades Directories will be found a copious Appendix, giving the present office - bearers and directorates of the various local public bodies and societies. The Publishers have pleasure in acknowledging the kind- ness of ladies and gentlemen connected with the various associations for supplying information, and also beg to thank their numerous Subscribers and Advertisers for their patronage. -

Prepared for State of Florida Department of Environmental Protection

Prepared for State of Florida Department of Environmental Protection 2020-2021 FLORIDA PUBLIC LANDS INVENTORY SUMMARIES OF GOVERNMENT AGENCIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS ORDERED BY COUNTY By The Public Lands Research Program Florida Resources and Environmental Analysis Center Florida State University Tallahassee, Florida http://www.floridapli.net January, 2021 How To Use This Summary The Report: SUMMARIES OF GOVERNMENT AGENCIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS ORDERED BY COUNTY shows the totals of property held by governmental agencies of the State and Federal Government, Municipalities, County Government, Special Districts, Volunteer Fire Departments, and Other Non-Profit entities. The report is generated in alphabetical order by county, but a governmental entity is not limited to land ownership in a particular county. There are nine columns of data relating to each government agency. Each column is described below. 1. Owner. This column list the name of the governmental agency or local government. A four-digit number precedes the name. This is the Public Lands Inventory (PLI) number used to match a parcel with a government agency. 2. Total Parcels. This is the total number of parcels for the government level. 3. Parcels AS S/D Lots. This shows the number of parcels given as subdivision lots. For these parcels, no acreage number can be obtained. 4. Parcels As Frontage. Parcels given as front foot or effective front foot. No acreage figure can be obtained. 5. Parcels With No Size Data. There is no information given regarding the size of the parcel. 6. Parcels With Acreage. The parcel size is given in acres, or was calculated to obtain an acreage figure. -

Monthly Permits Issue for Feb. 2021

HILLSBOROUGH COUNTY, FLORIDA RepID: HIll253A DEVELOPMENT SERVICES RunDate: 01-MAR-21 Permits Issued Report by Open Date Page 1 RunTime: 07:29 02/01/21 TO 02/28/21 ============================================================================================================================ SELECTION CRITERIA PERMIT TYPES - NCOM FCOM NCGB FCGB INTREM INTFIN SHELL FSHELL STATUS - ALL DATE SELECTION - OPEN SELECTION DATES - 02/01/21 TO 02/28/21 =========================================================================================================================== HILLSBOROUGH COUNTY, FLORIDA RepID: HIll253A DEVELOPMENT SERVICES RunDate: 01-MAR-21 Permits Issued Report by Open Date Page 2 RunTime: 07:29 02/01/21 TO 02/28/21 ============================================================================================================================ Activity: NCG21541 Type: NCGB Status: ISSUED Job Addr: 11796 EKKER RD , GIB 33534 Folio: 051425.1074 STR: Opened: 02/02/21 Valuation: $40,000.00 Sub: Lot: Block: Bldg#: Use: WB-Y/COM/INSTALL (2)SHADEPORT STRUCTURE/CONCRETE FOUDATION Liv Area: 0 Cov Area: 1000 Stories: 0 Units: 0 Contr: BREITWEISER STANLEY D Owner: PANTHER TRAILS CDD Firm: INDUSTRIAL SHADEPORTS INC Address: 6600 NW 12TH AVE, SUITE 220 Address: C/O RIZETTA & COMPANY INC Address: FORT LAUDERDALE, FL ,33309 Address: 3434 COLWELL AVE STE 200 ,33614-8390 Phone: 954-755-0661 License: CGC1525577 Activity: NCG21438 Type: NCGB Status: NOC Job Addr: 2611 E BEARSS AVE , TPA 33613 Folio: 034942.0000 STR: Opened: 02/02/21 Valuation: $60,155.00 -

City of Tampa Tree Canopy and Urban Forest Analysis 2016

City of Tampa Tree Canopy and Urban Forest Analysis 2016 City of Tampa Tree Canopy and Urban Forest Analysis 2016 Final Report to the City of Tampa March 2018 Authors Dr. Shawn M. Landry, University of South Florida Dr. Andrew K. Koeser, University of Florida Robert J. Northrop, UF/IFAS Extension, Hillsborough County Drew McLean, University of Florida Dr. Geoffrey Donovan, U.S. Forest Service Dr. Michael G. Andreu, University of Florida Deborah Hilbert, University of Florida Project Contributors Jan Allyn, University of South Florida Kathy Beck, City of Tampa Catherine Coyle, City of Tampa Rich Hammond, University of South Florida Eric Muecke, City of Tampa Jarlath O’Neil-Dunne, University of Vermont Dr. Ruiliang Pu, University of South Florida Cody Winter, University of South Florida Quiyan Yu, University of South Florida Special Thanks Fredrick Hartless, Hillsborough County Landowners and residents of the City of Tampa City of Tampa Urban Forest Management Internal Technical Working Group City of Tampa Natural Resources Advisory Committee Citation for this report: Landry S., Koeser, A., Northrop, R., McLean, D., Donovan, G., Andreu, M. & Hilbert, D. (2018). City of Tampa Tree Canopy and Urban Forest Analysis 2016. Tampa, FL: City of Tampa, Florida. Contents Executive Summary �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 9 The Benefits of Trees ................................................................................. 14 Project Methods Study Area ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������17 -

PO Box Mail Recycling – Participating Post Offices

PO Box Mail Recycling – Participating Post Offices ZIP State City Facility Name Address 00612 PR Arecibo Arecibo Post Office 10 Ave San Patricio 00680 PR Mayaguez Mayaguez Post Office 60 Calle McKinley W 00683 PR German SAN GERMAN PO 181 Calle Luna 00693 PR Veja Baja VEGA BAJA PO A-10 Calle 2 00725 PR Caguas CAG-NORTH STA Caguas North Station, Lincoln Ctr 00725 PR Caguas CAGUAS PO 225 Calle Gautier Benitez, 00730 PR Ponce Atocha Post Office 93 Calle Atocha 00731 PR Ponce PONCE PO 2340 Eduardo Ruperte 00777 PR Juncos JUNCOS PO 1Calle Munoz Rivera 00784 PR Guayama GUAYAMA PO 151 Ashford Ave 00791 PR Humacao HUMACAO PO 122 Calle Font Martelo 00802 VI St. Thomas Charlotte Amalie Post Office 9846 Estate Thomas 00802 VI St. Thomas Veterans Drive Post Office 6500 Veterans Drive 00820 VI Christiansted Christiansted Post Office 1104 Estate Richmond 00850 VI Kingshill Kingshill Post Office 2 Estate La Reine 00882 NJ Flemington FLEMINGTON PO 15 Main St 00901 PR San Juan OLD SAN JUAN 100 PASEO DE COLON STE 1 00906 PR San Juan SJU-PUERTA DE TIERRA STA Puerta De Tierra Station 00912 PR Arecibo ARECIBO PO 10 Ave San Patricio, 00918 PR San Juan HATO REY 361 CALLE JUAN CALAF 00918 PR San Juan Hato Rey Station 361 Calle Juan Calaf 00920 PR San Juan SJU-CAPARRA HEIGHTS STA 1505 Ave FD Roosevelt Ste 4 00924 PR San Juan 65TH INFANTRY 100 CALLE ALONDRA 00925 PR San Juan RIO PIEDRAS 112 CALLE ARZUAGA STE 1 00925 PR Rio Piedras SJU-RIO PIEDRAS STA 112 Calle Arzuaga 00936 PR San Juan General Post Office (MOWS) 585 Ave FD Roosevelt Ste 202 00936 PR San Juan SAN JUAN 585 AVE FD ROOSEVELT STE 370 00949 PR Toa Baja TOA BAJA 100 AVE LUIS MUNOZ RIVERA 00949 PR Toa Baja Toa Baja Post Office 600 Ave Comerio Ste 1 00957 PR Bayamon Bayamon Gardens Station 100 Victory Shopping Center Ste 1 00959 PR Bayamon Bayamon Branch Station 100 Ave Ramon R. -

Florida Postcard Collection (ASM0299)

University of Miami Special Collections Finding Aid - Florida Postcard Collection (ASM0299) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.0 Printed: May 22, 2018 Language of description: English University of Miami Special Collections 1300 Memorial Drive Coral Gables FL United States 33146 Telephone: (305) 284-3247 Fax: (305) 284-4027 Email: [email protected] https://library.miami.edu/specialcollections/ https://atom.library.miami.edu/index.php/asm0299 Florida Postcard Collection Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Series descriptions ........................................................................................................................................... 4 - Page 2 - ASM0299 Florida Postcard Collection Summary information Repository: University of Miami Special Collections Title: Florida Postcard Collection ID: ASM0299 Date: 1920-1990 (date of creation) Physical description: Boxes Dates of creation, revision and deletion: Scope and content Florida has long been a prime tourist destination, with its tropical environment, natural beauty, and numerous attractions. -

Public Involvement Plan

Public Involvement Plan FDOT District Seven JULY 2021 56th/50th Street Corridor Study 1 Public Involvement Plan (PIP) FPID 445651-1 PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PLAN (PIP) Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 4 2. DESCRIPTION OF STUDY / STUDY GOALS ............................................................................... 4 3. CONSULTANT TEAM ................................................................................................................. 7 4. PROJECT MILESTONES & SCHEDULES ..................................................................................... 8 5. DECISION MAKING FRAMEWORK ........................................................................................ 11 6. TARGET AUDIENCE & KEY ISSUES .......................................................................................... 13 7. PUBLIC INVOVEMENT STRATEGY .......................................................................................... 14 8. MANAGING POTENTIAL CHALLENGES ................................................................................ 19 9. PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT PLAN ................................................................................. 20 10. APPENDIX A: Stakeholder Contacts ................................................................................... 21 11. APPENDIX B: Scope of Services ........................................................................................... 27 56th/50th