Big Legal Battles Over Rights in Bands' Names by Stan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23

Case 3:17-cv-02423-VC Document 105 Filed 08/16/18 Page 1 of 6 1 2 3 4 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 5 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 6 7 CRAIG CHAQUICO, Case No. 17-cv-02423-MEJ 8 Plaintiff, ORDER RE: MOTION FOR RECONSIDERATION 9 v. Re: ECF. No. 97 10 DAVID FREIBERG, et al., 11 Defendants. 12 13 INTRODUCTION 14 On January 11, 2018, Plaintiff Craig Chaquico filed a motion to strike Defendants’1 15 counterclaim for tortious interference pursuant to California’s anti-SLAPP statute, Cal. Civ. Proc. 16 Code § 425.16. ECF No. 47. On July 10, 2018, the Court denied Chaquico’s motion. ECF No. 17 86 (“MTS Order”). Chaquico now moves for reconsideration. ECF No. 97. Defendants filed an United States District Court District United States Northern District of California District Northern 18 Opposition (ECF No. 101), and Chaquico filed a Reply (ECF No. 104). The Court finds this 19 matter suitable for disposition without oral argument and VACATES the September 6, 2018 20 hearing. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 78(b); Civ. L.R. 7-1(b). Having considered the parties’ positions, the 21 relevant legal authority, and the record in this case, the Court DENIES Chaquico’s motion for the 22 following reasons. 23 BACKGROUND 24 A more detailed factual background is set forth in the Court’s July 10 order. MTS Order at 25 1-4. Chaquico brings claims against Defendants for breach of contract and under the Lanham Act 26 27 1 Defendants and Counterclaimants are David Freiberg, Donny Baldwin, Chris Smith, Jude Gold, and Catherine Richardson. -

Bbn Brevard Business News

Brevard Business BBN News Vol. 33 No. 15 April 13, 2015 $1.00 A Weekly Space Coast Business Magazine with Publishing Roots in America since 1839 UCI marks its 20th year as provider in medical–imaging arena By Ken Datzman The American Cancer Society’s annual cancer–statistics report finds that a 22 percent drop in cancer mortality over two decades led to the avoidance of more than 1.5 million cancer deaths that would have occurred if peak rates had persisted. The information was released in two reports: “Cancer Statistics 2015,” published in “CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians,” and its companion, the consumer publication, “Cancer Facts & Figures 2015.” Each year, the ACS compiles the most recent data on cancer incidence, mortality, and survival based on incidence data from the National Cancer Institute, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the National Center for Health Statistics. Many factors have contributed to reduced cancer deaths in America, including advances in cancer prevention and early detection and treatment. Clearly, medical–imaging technol- ogy has been at the forefront of early detection and prolonging and saving lives. Various studies have linked the use of imaging examinations to longer life expect- ancy, declines in mortality, less need for exploratory surgery, fewer hospital admis- sions, and shorter lengths of hospital stays, according to research by the American College of Radiology and the Neiman Health Policy Institute, with other organizations also providing data for the report. Locally, one longtime business that special- izes in providing full medical–imaging services has seen firsthand the value of diagnostics, from both the patient and the physician perspective, and has internal data to support BBN photo — Adrienne B. -

Revista No. 44. Tema: Análisis De Resultados Electorales Y

Navega sin límite desde tu casa, por $349 1 al mes con hasta 10Mbps de velocidad. Equipo Conecta el módem tú mismo a 30 MSI desde y DISFRUTA 2 $20 al mes 4FSWJDJPEJTQPOJCMFQBSBTVDPOUSBUBDJØOZVTPÞOJDBNFOUFEFOUSPEFMUFSSJUPSJPOBDJPOBM-PT.CQTDPSSFTQPOEFOBMNÈYJNPBODIPEFCBOEBEJTQPOJCMFQBSBOBWFHBS MBDVBMQPESÈWBSJBSFOGVODJØOEFB MB[POBEFDPCFSUVSBFOMBRVFTFFODVFOUSFJOTUBMBEPFMNPEFNC EFMBUFDOPMPHÓBJOTUBMBEBZEJTQPOJCMFEFOUSPEFMB[POBEFDPCFSUVSBD MBDPODFOUSBDJØOEFUSÈöDPFOFMNPNFOUPFORVF TFFODVFOUSBDPOFDUBEPBMBSFENØWJMEFEBUPTEF5FMDFME MBDFSDBOÓBDPOJONVFCMFTRVFDVFOUFODPOCMPRVFBEPSFTEFTF×BM QFOBMFTZDÈSDFMFT F MBDBOUJEBEEFFRVJQPTDPOFDUBEPTBMNJTNPUJFNQPBMNPEFN ZG MPTNBUFSJBMFTEFDPOTUSVDDJØOEFMJONVFCMFFOEPOEFTFFODVFOUSFDPOFDUBEPFMNPEFN FOUSFPUSPT"1-*$"10-¶5*$"%&640+6450%& .&("#:5&4 .# "MBHPUBSMB DVPUBEF.#FTUBCMFDJEBDPNP6TP+VTUP QPESÈTDPOUJOVBSOBWFHBOEPJMJNJUBEBNFOUFDPOVOBWFMPDJEBEUPQBEBEF.CQTIBTUBFMUÏSNJOPEFMDJDMPEFGBDUVSBDJØO-B4*.$BSETØMPQPESÈTFSVUJMJ[BEBDPOFMNPEFNQSPQPSDJPOBEPZBQSPWJTJPOBEPDPOMBMÓOFBBTJHOBEB4JMB4*.FTDPMPDBEBFOVOFRVJQPEJTUJOUP FMTFSWJDJPTFSÈTVTQFOEJEPIBTUBRVFÏTUBTFBDPMPDBEBOVFWBNFOUFFOFMNPEFN &MNPEFNEFCFSÈQFSNBOFDFSFOMBVCJDBDJØODPOöHVSBEBFOTVQSJNFSOBWFHBDJØOTFTJØOEFEBUPT4JFMNPEFNFTDBNCJBEPEFVCJDBDJØO QPESÈTBDUVBMJ[BSMBVCJDBDJØODPODPTUPEF*7"JODMVJEPPNBOUFOFSMBQSFWJBNFOUFSFHJTUSBEB&ODBTPEFNBOUFOFSMBVCJDBDJØOQSFWJBNFOUFSFHJTUSBEB MBOBWFHBDJØOTFSÈJOUFSSVNQJEBIBTUBRVFFMNPEFNTFBDPMPDBEPOVFWBNFOUFFOMB VCJDBDJØOPSJHJOBMNFOUFDPOöHVSBEB*OGPSNBDJØOFOXXXUFMDFMDPNZ$FOUSPTEF"UFODJØOB$MJFOUFT5FMDFM-044&37*$*04%&70;:%"5044&13&45"/$0/'03.&"-04&45«/%"3&4&45"#-&$*%04&/-04-*/&".*&/50426&'*+"/-04¶/%*$&4:1"3«.&5304%&$"-*%"%"26&%&#&3«/46+&5"34&-0413&45"%03&4%&-4&37*$*0.»7*-7*(&/5&43FHJTUSP1ÞCMJDPEF5FMFDPNVOJDBDJPOFT -

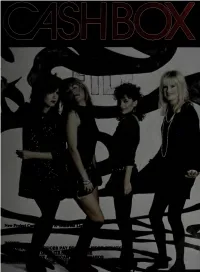

CB-1986-02-08.Pdf

- 'Jl6 CAPITOt ftECOnOS. INC. ON RECORDS AND HIGH QUALITY XOR® CASSETTES FROM CAPITOL CASH BOX THE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC / COIN MACHINE / HOME ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY VOLUME XLIX — NUMBER 34 — February 8, 1986 C4SHBO< GUEST EDITORIAL Handling Stress in Radio Records GEORGE ALBERT And President and Publisher By Dr. Keith C. Ferdinand MARK ALBERT Health is a state of mental, physical, and social well-being; it is not in your daily life is the first action to take in treating stress. If your work Vice President and General Manager merely the absence of disease. Stress may indeed be the number one cause place is impossible to deal with you may need a job change or at least SPENCE BERLAND of unhealthiness today. Americans are constantly subjected to stressful a change in schedule. Request a meeting with your boss after writing down Vice President situations; job dissatisfaction, economic insecurity, family conflict, and and outlining the problems that you see in your work place. Have available J.B. CARMICLE threats of physical attack. suggestions for possible solutions. Blowing off steam or “acting crazy" Vice President Men and women working in the communications is no substitute for a reasoned and constructive 7dAVID ADELSOli industry have a high level of work-related stress. suggestion session. This also indicates to those in Stress takes a heavy toll on the mind and body and greater authority that you have an ability to Managing Editor sometimes appears as unexplained sleep disturban- demonstrate control and maturity. If you cannot ROBERT LONG ces, headaches, loss of appetite, compulsive binge- make positive changes in your work place, consider Director Black/Urban Marketing eating, obesity, muscle tension, and a long list of other options, such as transferring to another area, JIMI FOX diseases. -

Beacher Page 102308-A.Indd

THE TM 911 Franklin Street Weekly Newspaper Michigan City, IN 46360 Volume 24, Number 42 Thursday, October 23, 2008 Paris in the Spring…Last Spring That Is by Charles McKelvy A Purposeful Posting to Paris with Wisconsin’s tem works.” Megan Maureen Wright While Meg Wright is waiting for the right word “Buffy Contre les Vampires,” pour vous? from France on her credits, let us take a fuel-free Well, if you had been with my niece, Megan trip with her across the Atlantic as she recounts her Maureen Wright, for the fabulous French adven- University of Wisconsin- ture by beginning with a Madison’s Paris, Spring quote from the immortal 2008 program, you would chanteuse Edith Piaf: “Je have sat with her and her ne regrette rien.” hosts, Patrice and Bea- Meaning that Meg trice Heran, and watched doesn’t regret a single poorly translated reruns nanosecond she spent in of what we commonly re- France and beyond this fer to as “Buffy the Vam- past spring. pire Slayer.” But why spring? A fourth-year French Well, Paris might, as and Communications Meg experienced, be cool Arts major with a cer- and rainy in the spring- tifi cate in Business, my time but, as she says: “I amazing niece Meg took chose to go in the spring off on February 18 for her because the idea of en- studies in Paris through joying a football season an American-based pro- and fall in Madison while gram center called Ac- avoiding the winter was cent, with side trips to just too good to pass up.” Italy, Germany, Ireland While she could have and the UK. -

Jefferson Starship

2008 BIOGRAPHIC INFORMATION JEFFERSON STARSHIP 2008 Bio Capsules PAUL KANTNER, along with MARTY BALIN founded JEFFERSON AIRPLANE in 1965. THE AIRPLANE were the biggest rock group in America during the 1960s and the first San Francisco band to sign a major record deal, paving the way for other legends like GRATEFUL DEAD & JANIS JOPLIN. They headlined the original WOODSTOCK FESTIVAL in 1969 and like THE BEATLES with whom they are critically compared, lasted a mere 7 years ... though their influence and impact on rock music continues well into the 21st century. In 1974 Mr. KANTNER created JEFFERSON STARSHIP and again with Mr. BALIN, enjoyed chart-topping success. PAUL, MARTY & JEFFERSON AIRPLANE were inducted into The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1996, the same year as PINK FLOYD. In 2005 they celebrated their 40th anniversary, playing 21 countries on their world tour. In 2007 they headlined “The Summer of Love 40th Anniversary Celebration” and performed at The Monterey Pop commemorative on the exact same stage as the historic landmark rock festival of 1967. JEFFERSON STARSHIP, the name created by PAUL for his 1971 solo debut “Blows Against The Empire” recording has endured 37 years as rock music’s premier “political science fiction” themed band. That recording was the first and only to ever be nominated for literary science fiction’s Hugo Award … a stellar achievement. DAVID FREIBERG is co-founder of the legendary Avalon/Carousel/Fillmore era San Francisco band who along with THE DEAD & THE AIRPLANE), often shared the bill. DAVID is an extraordinary singer, producer and multi- instrumentalist who plays guitar, bass, viola and keyboards. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23

Case 3:17-cv-02423-VC Document 25 Filed 08/11/17 Page 1 of 15 1 2 3 4 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 5 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 6 CRAIG CHAQUICO, 7 Case No. 17-cv-02423-MEJ Plaintiff, 8 ORDER RE: MOTION TO DISMISS v. 9 Re: Dkt. No. 14 DAVID FREIBERG, et al., 10 Defendants. 11 12 13 INTRODUCTION 14 Defendants David Freiberg, Donny Baldwin, Chris Smith, Jude Gold, and Catherine 15 Richardson (collectively, “Defendants”) move to dismiss Plaintiff Craig Chaquico‟s First 16 Amended Complaint (“FAC”) pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure (“Rule”) 12(b)(6). 17 Mot., Dkt. No. 14; see FAC, Dkt. No. 11. Plaintiff filed an Opposition (Dkt. No. 17) and United States District Court District United States Northern District of California District Northern 18 Defendants filed a Reply (Dkt. No. 18). The Court previously found this matter suitable for 19 disposition without oral argument. Dkt. No. 19. Having considered the parties‟ positions, the 20 relevant legal authority, and the record in this case, the Court GRANTS IN PART Defendants‟ 21 Motion for the following reasons. 22 BACKGROUND 23 In 1970, Plaintiff and nonparty Paul Kantner began recording music and performing 24 concerts with other musicians under the name “Jefferson Starship.” FAC ¶ 14. The original 25 lineup of Jefferson Starship included Chaquico, Kantner, Freiberg, and four other band members. 26 Id. ¶ 15. From its formation through 1985, Jefferson Starship released twenty platinum and gold 27 albums and reached the top of Billboard charts for multiple releases. Id. ¶ 16. Jefferson Starship‟s 28 members changed on several occasions; Chaquico was the sole member to participate in every Case 3:17-cv-02423-VC Document 25 Filed 08/11/17 Page 2 of 15 1 album, recording, music video, and tour throughout the band‟s existence. -

Five Minority Members of Polity Judiciary to Quit Move Protests 'Puppet' Role, Chief Among Them by Howard Saltz Dewayne Briggins, Victoria Chevalier Ing Tonight

Cuomo Is Elected Go verno] Moynihan, Carney, Lacks, Hochbrueckner Wii -Elecin Coverae IBOtu on Page 4 All Five Minority Members Of Polity Judiciary to Quit Move Protests 'Puppet' Role, Chief Among Them By Howard Saltz DeWayne Briggins, Victoria Chevalier ing tonight. They will leave five I_ rc d 4 Lr .;;. The five minority members of the Pol- and Sharon King, will end their one- members on tne »juaiciary. s ity Judiciary will resign tonight, effec- year terms six months prematurely In a statement read by Baxter, they tive Nov. 11, to protest actions-and after the Nov. 9 Polity run-off elections, charged that the Polity Council, the ! inactions-of other Polity sectors they which the Judiciary must verify. They executive branch of the undergraduate say force them to be a "puppet made the decision Sunday, Brown said, student government, has ignored their judiciary." after "weeks" of thinking about it. decisions, and has pressured some of the Chief Justice Van Brown, and asso- The resignations are expected to be five non-minority members of the Judi- ciate justices Virginia Baxter, formally tendered at a Judiciary meet- ciary into making decisions acceptable I s~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~M= % to the Council. Four of the five also lashed out at the university administra- tion for not forcing the Council to uphold Judiciary decisions. "We are continually interrupted in our efforts to act as a proper judiciary should act," Baxter said. "If the Council wants a puppet Judiciary, let them have -_-t one. We won't be a puppet Judiciary." By removing themselves. they said, university administrators, and ulti- mately the campus populace, will have to address minority students' rights. -

Jefferson Starship Rose from the Ashes of Another Legendary San Francisco Band, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Inductees, Jefferson Airplane

Jefferson Starship rose from the ashes of another legendary San Francisco band, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Inductees, Jefferson Airplane. Founder Paul Kantner (who died in January of 2016 at age 74) knew that combining powerful creative forces, personalities and talents could create something far greater than the sum of its parts. Between 1974 and 1984, Jefferson Starship released eight gold and platinum selling albums, twenty hit singles, sold out concerts worldwide and lived out legendary rock and roll escapades. "Jefferson Starship was my creation...and it has this nice fluidity about it that allows any number of people to come in and do things with whatever Jefferson Starship is." - Paul Kantner Today's Jefferson Starship remains dedicated to breathing new life into the living catalog of the Jeffersonian legacy, going to the edge, pushing the sonic boundaries and staying true to the original spirit of the music. Featuring original and historic members David Freiberg (also a founder of San Francisco luminaries Quicksilver Messenger Service) and drummer Donny Baldwin, along with longtime members Chris Smith on keyboards and synth bass, Jude Gold on lead guitar and GRAMMY Nominee Cathy Richardson anchoring the female lead vocal spot made famous by the inimitable Grace Slick. Richardson was invited by Ms. Slick to sing in her place when Jefferson Airplane accepts their Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2016 GRAMMY Merit Awards Concert and Telecast in April. The band keeps a hectic touring schedule bolstered by several television recent appearances including My Music: 60s Pop, Rock and Soul on PBS and live with the Contemporary Youth Orchestra on AXS Network. -

September 2018 Inside This Issue President’S Article! Event Photos! Event Flyers! 2019 Caravan Information! and More!

Newsletter of the Discovery Bay Corvette September 2018 Inside this Issue President’s Article! Event Photos! Event Flyers! 2019 Caravan Information! And More! Discovery Bay Corvette Club Executive Board 2018 Officers President Mark Zupan 925-366-7738 [email protected] Vice President Ed O’Brien 925-634-2634 [email protected] Treasurer Brian Enbom 925-516-7712 [email protected] Secretary Dave Peck 925-513-7532 [email protected] Events Shari Peck 925-513-7532 [email protected] Publications Laura Hardt 925-234-8430 [email protected] WSCC Rep. Dave Harris 925-437-3598 [email protected] Public Relations Danica Harris 925-516-0298 [email protected] Quartermaster Diana Cernera 925-240-5971 [email protected] Member-at-Large Lowell Onstad 510-552-1167 [email protected] Webmaster Ralph Cernera 925-240-5971 [email protected] Appointed Positions Sunshine Persons Paula Sauvadon 805-714-7877 [email protected] NCM Ambassador Dave Gatt 925- 513-1605 [email protected] Meeting Schedule: First Thursday of each month, except when otherwise noted. Next Meeting: October 4th 2018 7:30 pm Location: Discovery Bay Yacht Club Board Meeting 6:30 PM General Meeting 7:30 PM All members are urged to attend the meetings and guests are always welcome! Mailing address: PO Box 1158, Discovery Bay, CA 94505-1158 www.discoverybaycorvettelub.com 2 DBCC GENERAL MEETING MINUTES / ORDER OF BUSINESS DATE:_9-6-18 Call to Order – Time 7:33 PM by: President Mark Zupan. 30 Members present. President’s Report (Mark): Going away party in Manteca for Terry/Delia Berardy by friends in Manteca. -

Ameriserv Flood City Music Festival Some Things New for 2017

Contact: Terry Deitz [email protected] For immediate release: Press Release AmeriServ Flood City Music Festival some things new for 2017 AUGUST 4-5, 2017 Johnstown, PA (April 28, 2017) – AmeriServ, the Johnstown Area Heritage Association (JAHA), and SMG Worldwide Entertainment and Convention Venue Management (SMG) are excited to, once again, announce the Flood City Music Festival title sponsor as AmeriServ, and, to introduce a new addition to the team, SMG. AmeriServ is thrilled to continually support the festival as naming sponsor. AmeriServ first served as our title sponsor of the National Folk Festival in 1994. The organization remained the title sponsor during the relocation and renaming of the festival. In 2017, we are happy to still declare AmeriServ as the naming sponsor of the Flood City Music Festival. New this year, SMG will handle event management and talent booking duties. Also joining the coordinating efforts, we are pleased to announce Terry Deitz as the Festival Committee Chairman. These members are eager to work with us to create the ultimate experience for the community. Mark Pasquerilla, chairman on the JAHA’s Board of Directors stated, "I firmly believe that the team of SMG Johnstown and our JAHA team of volunteers, led by our Board Member and Flood City Music Fest Chair, Terry Deitz, will continue the legacy of this festival which is in its 28th year of providing a great musical weekend to our region!" "On behalf of SMG, we are excited to work alongside AmeriServ and JAHA in this venture. We are grateful for the opportunity to support this great event." said Steve St. -

STARSHIP Performs & Celebrates Music of JEFFERSON AIRPLANE’S 50Th Dedicated to PAUL KANTNER with Songs That Defined a Generation!

JEFFERSON STARSHIP Performs & Celebrates Music of JEFFERSON AIRPLANE’s 50th Dedicated to PAUL KANTNER With songs that defined a generation! San Francisco, CA (Jan. 29, 2016) — Jefferson Starship have resolved to continue the band and its astonishing musical legacy - carrying forward the 50th Anniversary of Jefferson Airplane and its co-founder Paul Kantner, as he had wished. Paul passed away yesterday in San Francisco at the age of 74. Jefferson Starship, comprised of legends David Freiberg & Donny Baldwin, and long time stalwarts Chris Smith & Jude Gold, alternate a coterie of brilliant female vocalists. This includes Darby Gould who, when the band re-formed in 1992 - assumed Grace Slick’s mantle (Grace retired in 1989); and, Cathy Richardson, who previously starred in “Love, Janis” and whose Jefferson Starship performance at Woodstock’s 40th Anniversary is legendary. David Freiberg co-founded Jefferson Starship in 1974; was also a Jefferson Airplane member, and co founded the legendary & influential Fillmore era band, Quicksilver Messenger Service in 1966. Jefferson Starship celebrated their 40th Anniversary in 2014. The band, descended from Jefferson Airplane who performed at Monterey and Woodstock, at Altamont with the Rolling Stones, and shared the bill countless times with Grateful Dead & Janis Joplin; and, whose music helped define a generation focused on civil rights, environmentalism and anti-war activism. Jefferson Starship performs their repertoire of hits spanning all eras of their existence, including “Jane,” “Somebody To Love,” “White Rabbit,” “Volunteers,” “Today,” “Embryonic Journey,” “Find Your Way Back,” “Miracles,” “Count On Me” and the hit songs of Quicksilver. .