Student Politics in Urban Ternate, North Maluku Basri Amin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This PDF File

KHAIRUN ISSN Print: 2580-9016 ISSN Online: 2581-1797 Law Journal Khairun Law Journal, Vol. 3 Issue 2, March 2020 Faculty of Law, Khairun University Efektifitas Penegakan Pelanggaran Administrasi Pada Pemiluhan Umum Anggota Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah Oleh Badan Pengawas Pemilihan Umum Tahun 2019 (Studi Terhadap Tugas Badan Pengawas Pemilihan Umum Halmahera Selatan) Ismed A. Gafur Mahsiswa Program Studi Magister Ilmu Hukum Program Pascasarjana Universitas Kahirun, Email : [email protected] Nam Rumkel Dosen Program Studi Magister Ilmu Hukum Program Pascasarjana Universitas Kahirun, Email : [email protected] Abdul Aziz Hakim Dosen Fakultas Hukum Universitas Muhammadiyah Maluku Utara, Email : [email protected] ABSTRACT With the enactment of Law Number 7 of 2017 concerning General Elections, it provides an opportunity for increased democracy by taking into account the violations committed and is the main task of the Regency / City General Election Supervisory Board. The effectiveness of enforcement of administrative violations by BAWASLU South Halmahera Regency based on Article 240 Paragraph (1) Letter (k) and (m) of Law Number 7 of 2017 concerning General Election, has not been maximized in giving decisions to Candidates for DPRD Members of South Halmahera Regency Dapil II Makian Kayoa who have met the formal and material elements in the Administrative Violation Trial examination. In addition, the factors that influence the enforcement of Administrative Violations in the General Election of DPRD Members by BAWASLU South Halmahera in 2019 are the number of personnel and supporting facilities in trial examinations inadequate, between duties and operational funds are not comparable in handling cases of administrative violations. Keywords: Administrative Violations, Concurrent General Elections, District BAWASLU Tasks. -

Foertsch 2016)

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Christopher R. Foertsch for the degree of Master of Arts in Applied Anthropology presented on June 3, 2016. Title: Educational Migration in Indonesia: An Ethnography of Eastern Indonesian Students in Malang, Java. Abstract approved: ______________________________________________________ David A. McMurray This research explores the experience of the growing number of students from Eastern Indonesia who attend universities on Java. It asks key questions about the challenges these often maligned students face as ethnic, linguistic, and religious minorities exposed to the dominant culture of their republic during their years of education. Through interviews and observations conducted in Malang, Java, emergent themes about this group show their resilience and optimism despite discrimination by their Javanese hosts. Findings also reveal their use of social networks from their native islands as a strategy for support and survival. ©Copyright by Christopher R. Foertsch June 3, 2016 All Rights Reserved Educational Migration in Indonesia: An Ethnography of Eastern Indonesian Students in Malang, Java by Christopher R. Foertsch A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Presented June 3, 2016 Commencement June 2017 Master of Arts thesis of Christopher R. Foertsch presented on June 3, 2016 APPROVED: Major Professor, representing Applied Anthropology Director of the School of Language, Culture, and Society Dean of the Graduate School I understand that my thesis will become part of the permanent collection of Oregon State University libraries. My signature below authorizes release of my thesis to any reader upon request. Christopher R. Foertsch, Author ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author expresses sincere appreciation to the many people whose support, advice, and wisdom was instrumental throughout the process of preparing, researching, and writing this thesis. -

Indonesia's Exquisite Birds of Paradise

INDONESIA'S EXQUISITE BIRDS OF PARADISE Whether you are a mere nestling who is new to bird watching, a Halmehera: Standard-wing (Wallace’s) Bird-of fully-fledged birder, or a seasoned twitcher, this 10-day (9-night) ornithological adventure through the remote, rainforest-clad islands of northern Raja Ampat and North Maluku, which includes a two-night stay at the famed Weda Resort on Halmahera, is a fantastic opportunity to add some significant numbers to your life lists. No other feathered family is as beautiful, or displays such diversity of plumage, extravagant decoration, and courtship behaviour as the ostentatious Bird of Paradise. In the company of our guest expert, Dr. Kees Groeneboer, we will be in hot pursuit of as many as six or seven species of these fabled shapeshifters, which strut, dazzle and dance in costumes worthy of the stage. -Paradise, Paradise Crow. Special birds in the Weda-Forest of Raja Ampat is one of the most noteworthy ecological niches on Halmahera Moluccan Goshawk, Moluccan Scrubfowl, Bare-eyed the planet, where you can snorkel within a below-surface world Rail, Drummer Rail, Scarletbreasted Fruit-Dove, Blue-capped reminiscent of a living kaleidoscope, while marveling at Fruit-Dove, Cinnamon-bellied Imperial Pigeon, Chattering Lory, above-surface views – and birds, which are among the most White (Alba) Cockatoo, Moluccan Cuckoo, Goliath Coucal, Blue stunning that you are likely to behold in a lifetime. Meanwhile, and-white Kingfisher, Sombre Kingfisher, Azure (Purple) Halmahera, in the North Maluku province, is where some of the Dollarbird, Ivory-breasted Pitta, Halmahera Cuckooshrike, world’s rarest and least-known birds occur. -

Of Halmahera, Indonesia

Blumea 59, 2015: 215–225 www.ingentaconnect.com/content/nhn/blumea RESEARCH ARTICLE http://dx.doi.org/10.3767/000651915X689091 Nepenthes (Nepenthaceae) of Halmahera, Indonesia M. Cheek1 Key words Abstract Two new paniculate species of Nepenthes, N. halmahera and N. weda, both allied to N. danseri Jebb & Cheek, are described respectively from lowland and lower montane forest on ultramafic substrate. Nepenthes weda character state appears to be unique in the genus due to the adaxial tepal surfaces which in the distal portion are hairy and lack critically endangered nectar glands. This species is also unique among paniculate members of the genus in its forward-facing, concave mining subapical lid appendage. Both species are currently only known from the Weda Bay Nickel Project concession area ultramafic in Halmahera, Indonesia, and are assessed as Critically Endangered using the 2012 IUCN standard. Two character Weda Bay Nickel Project states are formally described and named for the first time in Nepenthes: nanophyll rosettes and multiseriate fringed pitcher wings. Stage-related heteromorphy in lid appendages is documented for the first time in the genus. Keys to the species of Nepenthes of Halmahera, and to the paniculate species of SE Asia are presented. Published on 13 August 2015 INTRODUCTION the basal grade of the genus, in the west (Jebb & Cheek 1997, Mullins & Jebb 2009). Halmahera, is the largest island in Indonesia’s Maluku Province Until 1997, just two species were known from Maluku, Nepen- (formerly Moluccas) after Seram. The islands of Maluku are thes mirabilis (Lour.) Druce the most globally widespread spe- situated between Sulawesi (formerly Celebes) to the west, and cies (from Indo-China to N Australia), and N. -

Local Languages, Local Malay, and Bahasa Indonesia a Case Study from North Maluku

PB Wacana Vol. 14 No. 2 (October 2012) JOHN BOWDENWacana, Local Vol. 14languages, No. 2 (October local Malay, 2012): and 313–332 Bahasa Indonesia 313 Local languages, local Malay, and Bahasa Indonesia A case study from North Maluku JOHN BOWDEN Abstract Many small languages from eastern Indonesia are threatened with extinction. While it is often assumed that ‘Indonesian’ is replacing the lost languages, in reality, local languages are being replaced by local Malay. In this paper I review some of the reasons for this in North Maluku. I review the directional system in North Maluku Malay and argue that features like the directionals allow those giving up local languages to retain a sense of local linguistic identity. Retaining such an identity makes it easier to abandon local languages than would be the case if people were switching to ‘standard’ Indonesian. Keywords Local Malay, language endangerment, directionals, space, linguistic identity. 1 Introduction Maluku Utara is one of Indonesia’s newest and least known provinces, centred on the island of Halmahera and located between North Sulawesi and West Papua provinces. The area is rich in linguistic diversity. According to Ethnologue (Lewis 2009), the Halmahera region is home to seven Austronesian languages, 17 non-Austronesian languages and two distinct varieties of Malay. Although Maluku Utara is something of a sleepy backwater today, it was once one of the most fabled and important parts of the Indonesian archipelago and it became the source of enormous treasure for outsiders. Its indigenous clove crop was one of the inspirations for the great European age of discovery which propelled navigators such as Christopher Columbus and Ferdinand Magellan to set forth on their epic journeys across the globe. -

Integration and Conflict in Indonesia's Spice Islands

Volume 15 | Issue 11 | Number 4 | Article ID 5045 | Jun 01, 2017 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Integration and Conflict in Indonesia’s Spice Islands David Adam Stott Tucked away in a remote corner of eastern violence, in 1999 Maluku was divided into two Indonesia, between the much larger islands of provinces – Maluku and North Maluku - but this New Guinea and Sulawesi, lies Maluku, a small paper refers to both provinces combined as archipelago that over the last millennia has ‘Maluku’ unless stated otherwise. been disproportionately influential in world history. Largely unknown outside of Indonesia Given the scale of violence in Indonesia after today, Maluku is the modern name for the Suharto’s fall in May 1998, the country’s Moluccas, the fabled Spice Islands that were continuing viability as a nation state was the only place where nutmeg and cloves grew questioned. During this period, the spectre of in the fifteenth century. Christopher Columbus Balkanization was raised regularly in both had set out to find the Moluccas but mistakenly academic circles and mainstream media as the happened upon a hitherto unknown continent country struggled to cope with economic between Europe and Asia, and Moluccan spices reverse, terrorism, separatist campaigns and later became the raison d’etre for the European communal conflict in the post-Suharto presence in the Indonesian archipelago. The transition. With Yugoslavia’s violent breakup Dutch East India Company Company (VOC; fresh in memory, and not long after the demise Verenigde Oost-indische Compagnie) was of the Soviet Union, Indonesia was portrayed as established to control the lucrative spice trade, the next patchwork state that would implode. -

Local Trade Networks in Maluku in the 16Th, 17Th and 18Th Centuries

CAKALELEVOL. 2, :-f0. 2 (1991), PP. LOCAL TRADE NETWORKS IN MALUKU IN THE 16TH, 17TH, AND 18TH CENTURIES LEONARD Y. ANDAYA U:-fIVERSITY OF From an outsider's viewpoint, the diversity of language and ethnic groups scattered through numerous small and often inaccessible islands in Maluku might appear to be a major deterrent to economic contact between communities. But it was because these groups lived on small islands or in forested larger islands with limited arable land that trade with their neighbors was an economic necessity Distrust of strangers was often overcome through marriage or trade partnerships. However, the most . effective justification for cooperation among groups in Maluku was adherence to common origin myths which established familial links with societies as far west as Butung and as far east as the Papuan islands. I The records of the Dutch East India Company housed in the State Archives in The Hague offer a useful glimpse of the operation of local trading networks in Maluku. Although concerned principally with their own economic activities in the area, the Dutch found it necessary to understand something of the nature of Indigenous exchange relationships. The information, however, never formed the basis for a report, but is scattered in various documents in the form of observations or personal experiences of Dutch officials. From these pieces of information it is possible to reconstruct some of the complexity of the exchange in MaJuku in these centuries and to observe the dynamism of local groups in adapting to new economic developments in the area. In addition to the Malukans, there were two foreign groups who were essential to the successful integration of the local trade networks: the and the Chinese. -

North Maluku and Maluku Recovery Programme

NORTH MALUKU AND MALUKU RECOVERY PROGRAMME 19 September 2001 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction 4 II. North Maluku 5 A. Background 5 1. Overview of North Maluku 5 2. The Disturbances and Security Measures 6 3. Community Recovery and Reconciliation Efforts 7 B. Current Situation 12 III. Maluku 14 A. Background 14 1.Overview of Maluku 14 2. The Disturbances and Security Measures 16 3. Community Recovery and Reconciliation Efforts 18 B. Current Situation 20 IV. Reasons for UNDP Support 24 V. Programme Strategy 25 VI. Coordination, Execution, Implementation and Funding Arrangements 28 A. Governing Principles 28 B. Arrangements for Coordination 28 C. UN Agency Partnership and Coordination 29 D. Execution and Implementation Arrangements 30 E. Funding Arrangements 31 VII. Area of Programme Concentration and Target Beneficiaries 32 A. Area of Programme Concentration 32 B. Target Beneficiaries 33 VIII. Development Objective 34 IX. Immediate Objectives 35 X. Inputs 42 XI. Risks 42 XII. Programme Reviews, Reporting and Evaluation 42 XIII. Legal Context 43 XIV. Budget 44 2 Annexes I. Budget II. Terms of Reference of UNDP Trust Fund for Support to the North Maluku and Maluku Recovery Programme III. Terms of Reference: Programme Operations Manager/Team Leader – Jakarta IV. Terms of Reference: Recovery Programme Manager – Ternate and Ambon V. Chart of Reporting, Coordination and Implementation Relationships 3 NORTH MALUKU AND MALUKU RECOVERY PROGRAMME I. INTRODUCTION A. Context This programme of post-conflict recovery in North Maluku and Maluku is part of a wider UNDP effort to support post-conflict recovery and conflict prevention programmes in Indonesia. The wider programme framework for all the conflict-prone and post-conflict areas is required for several reasons. -

INTRODUCTION Prince Nuku of Tidore Is Recognized As One Of

INTRODUCTION Prince Nuku of Tidore is recognized as one of the national heroes (pahlawan nasional) of Indonesia. He was the leader of a successful rebel- lion against the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, VOC) and its indigenous allies which lasted for more than twenty years. Born as a Tidoran prince between 1725 and 1735, he passed away as the Sultan of Tidore in 1805.1 In 1780 he fled from Tidore seek- ing refuge in East Seram, Halmahera, and the Raja Ampat from where he launched the rebellion. In 1797 he returned to Tidore with his allied forces and conquered the Sultanates of both Bacan and Tidore. During his exile, Nuku had to fight the forces of the three VOC Governments in Maluku: Ternate, Ambon, and Banda.2 Besides possessing better weapon- ry and equipment, the VOC could also mobilize its indigenous subjects from places such as Ambon and Ternate as troops. In addition, the VOC often dispatched support forces such as ships, weaponry, and soldiers to Maluku from Batavia. In 1801, in close collaboration with the English, Nuku managed to defeat the VOC in Ternate and its indigenous ally, the Ternate Sultanate. Prince Nuku and his Tidoran adherents depended to a large extent on the support they received from various groups of Malukans and Papuans and the assistance of the English. It is intriguing to see what strategies he employed to maintain support among the Tidorans at home, his adher- ents in the periphery of Tidore, and even the English. Geographical and historical setting In the early sixteenth century, Maluku—known as the Spice Islands— became the target of European traders who were competing to obtain cloves and nutmegs. -

Profil Kabupaten Halmahera Utara

I RPI2-JM I Kabupaten Halmahera Utara I 04 PROFIL KABUPATEN HALMAHERA UTARA 4.1 PROFIL GEOGRAFIS 4.1.1 LETAK ASTRONOMIS Secara ASTRONOMIS Wilayah Kabupaten Halmahera Utara berada pada posisi koordinat: 0050’00” sampai 2022’10” LU dan 127°34'50” sampai 12808'30” BT. Itu berarti Wilayah Kabupaten Halmahera Utara berada di belahan bumi bagian Utara dan belahan bumi bagian Timur. 4.1.2 LETAK GEOGRAFIS DAN ADMINISTRASI Secara Geografis & Administrasi, batas wilayah Kabupaten Halmahera Utara, adalah: Sebelah Utara, berbatasan dengan Samudera Pasifik. Sebelah Timur, berbatasan dengan Kecamatan Wasilei Kabupaten Halmahera Timur, dan Laut Halmahera. Sebelah Selatan, berbatasan dengan Kecamatan Jailolo Selatan Kabupaten Halmahera Barat. Sebelah Barat, berbatasan dengan Kecamatan: Loloda, Sahu, Ibu, dan Jailolo Kabupaten Halmahera Barat. 4.1.3 LUAS WILAYAH Berdasarkan UU No. 1/2003 Kabupaten Halmahera Utara memiliki luas wilayah + 24.983,32 km2 yang meliputi wilayah laut: 19.563,08 km2 (78 %), wilayah daratan: 5.420,24 km2 (22 %) dan berjarak 138 mil laut dari Ternate/ Ibukota Kabupaten Halmahera Utara. Dengan adanya pemekaran Kabupaten Pulau Morotai (UU No. 53/2008), luas wilayah Kabupaten Halmahera Utara ± 22.507,32 km² meliputi luas daratan 4.951,61 km² (22%) dan lautan seluas 17.555,71 km² (78%).Kabupaten Halmahera Utara yang Bantuan Teknis RPI2JM Dalam Implementasi Kebijakan Keterpaduan Program IV - 1 Bidang Cipta Karya – Provinsi Maluku Utara Tahun 2014 I RPI2-JM I Kabupaten Halmahera Utara I mencakup pulau-pulau kecil lainnya di bagian utara Pulau Halmahera, memiliki tipologi lingkungan yang khas, dimana tidak hanya memiliki alam pegunungan tetapi juga memiliki areal pesisir pantai (coastal area) dengan berbagai sumber daya alam yang prospektif untuk dikembangkan. -

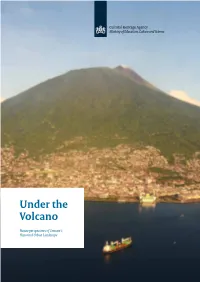

Under the Volcano

Under the Volcano Future perspectives of Ternate’s Historical Urban Landscape Under the Volcano Future perspectives of Ternate’s Historical Urban Landscape Under the Volcano Future perspectives of Ternate’s Historical Urban Landscape Report of the Ternate Conservation and Development Workshop Kota Ternate, 24-28 September 2012 Jean-Paul Corten, Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands Maulana Ibrahim, Universitas Khairun, Ternate, Indonesia Students of Universitas Khairun: Abdul Malik Pellu Arie Hendra Dessy Prawasti Ikbal Akili Irfan Jubbai Marasabessy Kodradi A.K. Sero Sero Rosmiati Hamisi Surahman Marsaoly Members of Ternate Heritage Society: Azwar Ahmad A. Fachrudin A.B. M. Diki Dabi Dabi Ridwan Ade Colophon Department: Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands Ministry of Education, Culture and Science Project name: Ternate Conservation and Development Workshop Version: 1.0 Date: July 2016 Contact: Jean-Paul Corten [email protected] Authors: Jean-Paul Corten, Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands Maulana Ibrahim, Universitas Khairun, Ternate, Indonesia Photo’s: Maulana Ibrahim Cover image: The Island of Ternate seen from the air (Maulana Ibrahim 2012) Design: En Publique, Utrecht Print: Xerox/OTB, The Hague © Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, Amersfoort 2016 Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands P.O.Box 1600 3800 BP Amersfoort the Netherlands culturalheritageagency.nl/en Content 1. Introduction 7 2. Historical Urban Landscapes 9 3. Past developments 11 4. Present situation 15 Urban quality 15 Technical condition 16 Current use 18 Strengths and weaknesses 18 5. Future perspectives 21 Development opportunities and risks 21 Restoration need 22 Participating students of the Khairun University (Maulana Ibrahim 2012) 6 — Map of Northern Maluku 1. -

Sultan Zainal Abidin Syah: from the Kingdomcontents of Tidore to the Republic of Indonesia Foreword

TAWARIKH:TAWARIKH: Journal Journal of Historicalof Historical Studies Studies,, VolumeVolume 12(1), 11(2), October April 2020 2020 Volume 11(2), April 2020 p-ISSN 2085-0980, e-ISSN 2685-2284 ABDUL HARIS FATGEHIPON & SATRIONO PRIYO UTOMO Sultan Zainal Abidin Syah: From the KingdomContents of Tidore to the Republic of Indonesia Foreword. [ii] JOHANABSTRACT: WAHYUDI This paper& M. DIEN– using MAJID, the qualitative approach, historical method, and literature review The– discussesHajj in Indonesia Zainal Abidin and Brunei Syah as Darussalam the first Governor in XIX of – WestXX AD: Irian and, at the same time, as Sultan of A ComparisonTidore in North Study Maluku,. [91-102] Indonesia. The results of this study indicate that the political process of the West Irian struggle will not have an important influence in the Indonesian revolution without the MOHAMMADfirmness of the IMAM Tidore FARISI Sultanate, & ARY namely PURWANTININGSIH Sultan Zainal Abidin, Syah. The assertion given by Sultan TheZainal September Abidin 30 Syahth Movement in rejecting and the Aftermath results of in the Indonesian KMB (Konferensi Collective Meja Memory Bundar or Round Table andConference) Revolution: in A 1949, Lesson because for the the Nation KMB. [103-128]sought to separate West Irian from Indonesian territory. The appointment of Zainal Abidin Syah as Sultan took place in Denpasar, Bali, in 1946, and his MARYcoronation O. ESERE, was carried out a year later in January 1947 in Soa Sio, Tidore. Zainal Abidin Syah was Historicalas the first Overview Governor of ofGuidance West Irian, and which Counselling was installed Practices on 23 inrd NigeriaSeptember. [129-142] 1956. Ali Sastroamidjojo’s Cabinet formed the Province of West Irian, whose capital was located in Soa Sio.