Conversations with the Past: Hans Pfitzner's" Palestrina" As a Neo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zelenka I Penitenti Al Sepolchro Del Redentore, Zwv 63

ZELENKA I PENITENTI AL SEPOLCHRO DEL REDENTORE, ZWV 63 COLLEGIUM 1704 COLLEGIUM VOCALE 1704 VÁCLAV LUKS MENU TRACKLIST TEXTE EN FRANÇAIS ENGLISH TEXT DEUTSCH KOMMENTAR ALPHA COLLECTION 84 I PENITENTI AL SEPOLCHRO DEL REDENTORE, ZWV 63 JAN DISMAS ZELENKA (1679-1745) 1 SINFONIA. ADAGIO – ANDANTE – ADAGIO 7’32 2 ARIA [DAVIDDE]. SQUARCIA LE CHIOME 10’08 3 RECITATIVO SECCO [DAVIDDE]. TRAMONTATA È LA STELLA 1’09 4 RECITATIVO ACCOMPAGNATO [MADDALENA]. OIMÈ, QUASI NEL CAMPO 1’21 5 ARIA [MADDALENA]. DEL MIO AMOR, DIVINI SGUARDI 10’58 6 RECITATIVO SECCO [PIETRO]. QUAL LA DISPERSA GREGGIA 1’38 7 ARIA [PIETRO]. LINGUA PERFIDA 6’15 8 RECITATIVO SECCO [MADDALENA]. PER LA TRACCIA DEL SANGUE 0’54 4 MENU 9 ARIA [MADDALENA]. DA VIVO TRONCO APERTO 11’58 10 RECITATIVO ACCOMPAGNATO [DAVIDDE]. QUESTA CHE FU POSSENTE 1’25 11 ARIA [DAVIDDE]. LE TUE CORDE, ARPE SONORA 8’31 12 RECITATIVO SECCO [PIETRO]. TRIBUTO ACCETTO PIÙ, PIÙ GRATO DONO RECITATIVO SECCO [MADDALENA]. AL DIVIN NOSTRO AMANTE RECITATIVO SECC O [DAVIDDE]. QUAL IO SOLEVA UN TEMPO 2’34 13 CORO E ARIA [DAVIDDE]. MISERERE MIO DIO 7’07 TOTAL TIME: 71’30 5 MARIANA REWERSKI CONTRALTO MADDALENA ERIC STOKLOSSA TENOR DAVIDDE TOBIAS BERNDT BASS PIETRO COLLEGIUM 1704 HELENA ZEMANOVÁ FIRST VIOLIN SUPER SOLO MARKÉTA KNITTLOVÁ, JAN HÁDEK, EDUARDO GARCÍA, ELEONORA MACHOVÁ, ADÉLA MIŠONOVÁ VIOLIN I JANA CHYTILOVÁ, SIMONA TYDLITÁTOVÁ, PETRA ŠCEVKOVÁ, KATERINA ŠEDÁ, MAGDALENA MALÁ VIOLIN II ANDREAS TORGERSEN, MICHAL DUŠEK, LYDIE CILLEROVÁ, DAGMAR MAŠKOVÁ VIOLA LIBOR MAŠEK, HANA FLEKOVÁ CELLO ONDREJ BALCAR, ONDREJ ŠTAJNOCHR -

The Ethics of Orchestral Conducting

Theory of Conducting – Chapter 1 The Ethics of Orchestral Conducting In a changing culture and a society that adopts and discards values (or anti-values) with a speed similar to that of fashion as related to dressing or speech, each profession must find out the roots and principles that provide an unchanging point of reference, those principles to which we are obliged to go back again and again in order to maintain an adequate direction and, by carrying them out, allow oneself to be fulfilled. Orchestral Conducting is not an exception. For that reason, some ideas arise once and again all along this work. Since their immutability guarantees their continuance. It is known that Music, as an art of performance, causally interlinks three persons: first and closely interlocked: the composer and the performer; then, eventually, the listener. The composer and his piece of work require the performer and make him come into existence. When the performer plays the piece, that is to say when he makes it real, perceptive existence is granted and offers it to the comprehension and even gives the listener the possibility of enjoying it. The composer needs the performer so that, by executing the piece, his work means something for the listener. Therefore, the performer has no self-existence but he is performer due to the previous existence of the piece and the composer, to whom he owes to be a performer. There exist a communication process between the composer and the performer that, as all those processes involves a sender, a message and a receiver. -

May 2018 List

May 2018 Catalogue Issue 25 Prices valid until Wednesday 27 June 2018 unless stated otherwise 0115 982 7500 [email protected] Your Account Number: {MM:Account Number} {MM:Postcode} {MM:Address5} {MM:Address4} {MM:Address3} {MM:Address2} {MM:Address1} {MM:Name} 1 Welcome! Dear Customer, Glorious sunshine and summer temperatures prevail as this foreword is being written, but we suspect it will all be over by the time you are reading it! On the plus side, at least that means we might be able to tempt you into investing in a little more listening material before the outside weather arrives for real… We were pleasantly surprised by the number of new releases appearing late April and into May, as you may be able to tell by the slightly-longer-than-usual new release portion of this catalogue. Warner & Erato certainly have plenty to offer us, taking up a page and half of the ‘priorities’ with new recordings from Nigel Kennedy, Philippe Jaroussky, Emmanuel Pahud, David Aaron Carpenter and others, alongside some superbly compiled boxsets including a Massenet Opera Collection, performances from Joseph Keilberth (in the ICON series), and two interesting looking Debussy collections: ‘Centenary Discoveries’ and ‘His First Performers’. Rachel Podger revisits Vivaldi’s Four Seasons for Channel Classics (already garnering strong reviews), Hyperion offer us five new titles including Schubert from Marc-Andre Hamelin and Berlioz from Lawrence Power and Andrew Manze (see ‘Disc of the Month’ below), plus we have strong releases from Sandrine Piau (Alpha), the Belcea Quartet joined by Piotr Anderszewski (also Alpha), Magdalena Kozena (Supraphon), Osmo Vanska (BIS), Boris Giltberg (Naxos) and Paul McCreesh (Signum). -

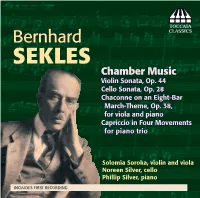

Toccata Classics TOCC0147 Notes

TOCCATA Bernhard CLASSICS SEKLES Chamber Music Violin Sonata, Op. 44 Cello Sonata, Op. 28 Chaconne on an Eight-Bar March-Theme, Op. 38, for viola and piano ℗ Capriccio in Four Movements for piano trio Solomia Soroka, violin and viola Noreen Silver, cello Phillip Silver, piano INCLUDES FIRST RECORDING REDISCOVERING BERNHARD SEKLES by Phillip Silver he present-day obscurity of Bernhard Sekles illustrates how porous is contemporary knowledge of twentieth-century music: during his lifetime Sekles was prominent as teacher, administrator and composer alike. History has accorded him footnote status in two of these areas of endeavour: as an educator with an enviable list of students, and as the Director of the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt from 923 to 933. During that period he established an opera school, much expanded the area of early-childhood music-education and, most notoriously, in 928 established the world’s irst academic class in jazz studies, a decision which unleashed a storm of controversy and protest from nationalist and fascist quarters. But Sekles was also a composer, a very good one whose music is imbued with a considerable dose of the unexpected; it is traditional without being derivative. He had the unenviable position of spending the prime of his life in a nation irst rent by war and then enmeshed in a grotesque and ultimately suicidal battle between the warring political ideologies that paved the way for the Nazi take-over of 933. he banning of his music by the Nazis and its subsequent inability to re-establish itself in the repertoire has obscured the fact that, dating back to at least 99, the integration of jazz elements in his works marks him as one of the irst European composers to use this emerging art-form within a formal classical structure. -

Paul Collins (Ed.), Renewal and Resistance Journal of the Society

Paul Collins (ed.), Renewal and Resistance PAUL COLLINS (ED.), RENEWAL AND RESISTANCE: CATHOLIC CHURCH MUSIC FROM THE 1850S TO VATICAN II (Bern: Peter Lang, 2010). ISBN 978-3-03911-381-1, vii+283pp, €52.50. In Renewal and Resistance: Catholic Church Music from the 1850s to Vatican II Paul Collins has assembled an impressive and informative collection of essays. Thomas Day, in the foreword, offers a summation of them in two ways. First, he suggests that they ‘could be read as a collection of facts’ that reveal a continuing cycle in the Church: ‘action followed by reaction’ (1). From this viewpoint, he contextualizes them, demonstrating how collectively they reveal an ongoing process in the Church in which ‘(1) a type of liturgical music becomes widely accepted; (2) there is a reaction to the perceived in- adequacies in this music, which is then altered or replaced by an improvement ... The improvement, after first encountering resistance, becomes widely accepted, and even- tually there is a reaction to its perceived inadequacies—and on the cycle goes’ (1). Second, he notes that they ‘pick up this recurring pattern at the point in history where Roman Catholicism reacted to the Enlightenment’ (3). He further contextualizes them, revealing how the pattern of action and reaction—or renewal and resistance—explored in this particular volume is strongly influenced by the Enlightenment, an attempt to look to the power of reason as a more beneficial guide for humanity than the authority of religion and perceived traditions (4). As the Enlightenment -

Interpreting Race and Difference in the Operas of Richard Strauss By

Interpreting Race and Difference in the Operas of Richard Strauss by Patricia Josette Prokert A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Jane F. Fulcher, Co-Chair Professor Jason D. Geary, Co-Chair, University of Maryland School of Music Professor Charles H. Garrett Professor Patricia Hall Assistant Professor Kira Thurman Patricia Josette Prokert [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-4891-5459 © Patricia Josette Prokert 2020 Dedication For my family, three down and done. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family― my mother, Dev Jeet Kaur Moss, my aunt, Josette Collins, my sister, Lura Feeney, and the kiddos, Aria, Kendrick, Elijah, and Wyatt―for their unwavering support and encouragement throughout my educational journey. Without their love and assistance, I would not have come so far. I am equally indebted to my husband, Martin Prokert, for his emotional and technical support, advice, and his invaluable help with translations. I would also like to thank my doctorial committee, especially Drs. Jane Fulcher and Jason Geary, for their guidance throughout this project. Beyond my committee, I have received guidance and support from many of my colleagues at the University of Michigan School of Music, Theater, and Dance. Without assistance from Sarah Suhadolnik, Elizabeth Scruggs, and Joy Johnson, I would not be here to complete this dissertation. In the course of completing this degree and finishing this dissertation, I have benefitted from the advice and valuable perspective of several colleagues including Sarah Suhadolnik, Anne Heminger, Meredith Juergens, and Andrew Kohler. -

Ernst Toch Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft0z09n428 No online items Ernst Toch papers, ca. 1835-1988 Finding aid prepared by UCLA Library Special Collections staff and Kendra Wittreich; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2008 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Ernst Toch papers, ca. 1835-1988 PASC-M 1 1 Title: Ernst Toch papers Collection number: PASC-M 1 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: German Physical Description: 44.0 linear ft.(88 boxes) Date (inclusive): ca. 1835-1988 Abstract: The Collection consists of materials relating to the Austrian-American composer, Ernst Toch. Included are music manuscripts and scores, books of his personal library, manuscripts, biographical material, correspondence, articles, essays, speeches, lectures, programs, clippings, photographs, sound recordings, financial records, and memorabilia. Also included are manuscripts and published works of other composers, as well as Lilly Toch's letters and lectures. Language of Materials: Materials are in English. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Creator: Toch, Ernst 1887-1964 Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. -

Otto Klemperer Curriculum Vitae

Dick Bruggeman Werner Unger Otto Klemperer Curriculum vitae 1885 Born 14 May in Breslau, Germany (since 1945: Wrocław, Poland). 1889 The family moves to Hamburg, where the 9-year old Otto for the first time of his life spots Gustav Mahler (then Kapellmeister at the Municipal Theatre) out on the street. 1901 Piano studies and theory lessons at the Hoch Conservatory, Frankfurt am Main. 1902 Enters the Klindworth-Scharwenka Conservatory in Berlin. 1905 Continues piano studies at Berlin’s Stern Conservatory, besides theory also takes up conducting and composition lessons (with Hans Pfitzner). Conducts the off-stage orchestra for Mahler’s Second Symphony under Oskar Fried, meeting the composer personally for the first time during the rehearsals. 1906 Debuts as opera conductor in Max Reinhardt’s production of Offenbach’s Orpheus in der Unterwelt, substituting for Oskar Fried after the first night. Klemperer visits Mahler in Vienna armed with his piano arrangement of his Second Symphony and plays him the Scherzo (by heart). Mahler gives him a written recommendation as ‘an outstanding musician, predestined for a conductor’s career’. 1907-1910 First engagement as assistant conductor and chorus master at the Deutsches Landestheater in Prague. Debuts with Weber’s Der Freischütz. Attends the rehearsals and first performance (19 September 1908) of Mahler’s Seventh Symphony. 1910 Decides to leave the Jewish congregation (January). Attends Mahler’s rehearsals for the first performance (12 September) of his Eighth Symphony in Munich. 1910-1912 Serves as Kapellmeister (i.e., assistant conductor, together with Gustav Brecher) at Hamburg’s Stadttheater (Municipal Opera). Debuts with Wagner’s Lohengrin and conducts guest performances by Enrico Caruso (Bizet’s Carmen and Verdi’s Rigoletto). -

Lincolnshire Posy Abbig

A Historical and Analytical Research on the Development of Percy Grainger’s Wind Ensemble Masterpiece: Lincolnshire Posy Abbigail Ramsey Stephen F. Austin State University, Department of Music Graduate Research Conference 2021 Dr. David Campo, Advisor April 13, 2021 Ramsey 1 Introduction Percy Grainger’s Lincolnshire Posy has become a staple of wind ensemble repertoire and is a work most professional wind ensembles have performed. Lincolnshire Posy was composed in 1937, during a time when the wind band repertoire was not as developed as other performance media. During his travels to Lincolnshire, England during the early 20th century, Grainger became intrigued by the musical culture and was inspired to musically portray the unique qualities of the locals that shared their narrative ballads through song. While Grainger’s collection efforts occurred in the early 1900s, Lincolnshire Posy did not come to fruition until it was commissioned by the American Bandmasters Association for their 1937 convention. Grainger’s later relationship with Frederick Fennell and Fennell’s subsequent creation of the Eastman Wind Ensemble in 1952 led to the increased popularity of Lincolnshire Posy. The unique instrumentation and unprecedented performance ability of the group allowed a larger audience access to this masterwork. Fennell and his ensemble’s new approach to wind band performance allowed complex literature like Lincolnshire Posy to be properly performed and contributed to establishing wind band as a respected performance medium within the greater musical community. Percy Grainger: Biography Percy Aldridge Grainger was an Australian-born composer, pianist, ethnomusicologist, and concert band saxophone virtuoso born on July 8, 1882 in Brighton, Victoria, Australia and died February 20, 1961 in White Plains, New York.1 Grainger was the only child of John Harry Grainger, a successful traveling architect, and Rose Annie Grainger, a self-taught pianist. -

Honorary Members, Rings of Honour, the Nicolai Medal and the “Yellow” List)

Oliver Rathkolb Honours and Awards (Honorary Members, Rings of Honour, the Nicolai Medal and the “Yellow” List) A compilation of the bearers of rings of honour was produced in preparation for the Vienna Philharmonic's centennial celebrations.1 It can not currently be reconstructed when exactly the first rings were awarded. In the archive of the Vienna Philharmonic, there are clues to a ring from 19282, and it follows from an undated index “Ehrenmitglieder, Träger des Ehrenrings, Nicolai Medaillen“3 that the second ring bearer, the Kammersänger Richard Mayr, had received the ring in 1929. Below the list of the first ring bearers: (Dates of the bestowal are not explicitly noted in the original) Dr. Felix von Weingartner (honorary member) Richard Mayr (Kammersänger, honorary member) Staatsrat Dr. Wilhelm Furtwängler (honorary member) Medizinalrat Dr. Josef Neubauer (honorary member) Lotte Lehmann (Kammersängerin) Elisabeth Schumann (Kammersängerin) Generalmusikdirektor Prof. Hans Knappertsbusch (March 12, 1938 on the occasion of his 50th birthday) In the Nazi era, for the first time (apart from Medizinalrat Dr. Josef Neubauer) not only artists were distinguished, but also Gen. Feldmarschall Wilhelm List (unclear when the ring was presented), Baldur von Schirach (March 30, 1942), Dr. Arthur Seyß-Inquart (March 30, 1942). 1 Archive of the Vienna Philharmonic, Depot State Opera, folder on the centennial celebrations 1942, list of the honorary members. 2 Information Dr. Silvia Kargl, AdWPh 3 This undated booklet was discovered in the Archive of the Vienna Philharmonic during its investigation by Dr. Silvia Kargl for possibly new documents for this project in February 2013. 1 Especially the presentation of the ring to Schirach in the context of the centennial celebration was openly propagated in the newspapers. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

Johann Joseph Fux (1660-1741) 10 Sonata a 4 in G Minor, K.347 7’16 11 Omnis Terra Adoret, K.183 8’05

BIBER REQUIEM VOX LUMINIS FREIBURGER BAROCKCONSORT LIONEL MEUNIER MENU › TRACKLIST › FRANÇAIS › ENGLISH › DEUTSCH › SUNG TEXTS CHRISTOPH BERNHARD (1628-1692) 1 HERR, NUN LÄSSEST DU DEINEN DIENER 13’02 2 TRIBULARER SI NESCIREM 5’40 JOHANN MICHAEL NICOLAI (1629-1685) 3 SONATA A 6 IN A MINOR 7’36 HEINRICH BIBER (1644-1704) REQUIEM IN F MINOR, C 8 4 Introitus 3’46 5 Kyrie 1’53 6 Dies irae 8’25 7 Offertorium 4’33 8 Sanctus 4’46 9 Agnus Dei – Communio 6’58 JOHANN JOSEPH FUX (1660-1741) 10 SONATA A 4 IN G MINOR, K.347 7’16 11 OMNIS TERRA ADORET, K.183 8’05 TOTAL TIME: 72’08 VOX LUMINIS VICTORIA CASSANO, PERRINE DEVILLERS, SARA JÄGGI, CRESSIDA SHARP, ZSUZSI TÓTH, STEFANIE TRUE SOPRANOS ALEXANDER CHANCE, JAN KULLMANN ALTOS ROBERT BUCKLAND, PHILIPPE FROELIGER TENORS LIONEL MEUNIER, SEBASTIAN MYRUS BASSES FREIBURGER BAROCKCONSORT VERONIKA SKUPLIK, PETRA MülleJANS VIOLIN CHRISTA KITTEL, WERNER SALLER VIOLA HILLE PERL VIOLA DA GAMBA ANNA SCHALL, MARLEEN LEICHER CORNETTO SIMEN VAN MECHELEN ALTO TROMBONE MIGUEL TANTOS SEVILLANO TENOR TROMBONE JOOST SWINKELS BASS TROMBONE CARLES CRISTOBAL DULCIAN JAMES MUNRO VIOLONE LEE SANTANA LUTE TORSTEN JOHANN ORGAN LIONEL MEUNIER ARTISTIC DIRECTOR HERR, NUN LÄSSEST DU DEINEN DIENER Coro Primo C.S, S.J, J.K, P.F, L.M Coro Secondo P.D, V.C, A.C, R.B, S.M Gott gab herzbrennende Begier C.S, S.J Den Heiland, den verlangten Glanz J.K, P.F Ein Licht, das finstre Heidenthum S.M TRIBULARER SI NESCIREM Coro Primo S.T, V.C, A.C, R.B, L.M Coro Secondo P.D, S.J, J.K, P.F, S.M Vivo ego et nolo S.M Sed ut magis convertatur et