Ex-Communist Witnesses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

46 ROSENBERG GRAND JURY WITNESSES (Testimony to Be

46 ROSENBERG GRAND JURY WITNESSES (testimony to be released September 11, 2008) Government is not releasing testimony of William Danziger, Max Elichter, and David Greenglass The descriptions provided below are based on available evidence. Additional details will be added after the transcripts are reviewed. 1. Ruth Alscher Ruth Alscher was Max Elitcher’s sister‐in‐law. She was married to his brother, Morris Alscher. In interviews with the FBI, Max and Helene Elitcher said that Ruth Alscher attended a party in 1944 in New York with them that was attended by three individuals who the Bureau suspected were Soviet agents: Julius Rosenberg, Joel Barr and William Perl. She also attended parties at a Greenwich Village apartment that Barr and another Soviet agent, Alfred Sarant, shared. Ruth Alscher was a friend of Bernice Levin; Levin was identified as a Soviet agent by Elizabeth Bentley. Assistant U.S. Attorney John W. Foley confidentially told the FBI in 1951 that Ruth Alscher had asserted privileges under the Fifth Amendment when called to testify to the Rosenberg grand jury. At the time of the Rosenberg/Sobell trial, Morris Alscher had died, leaving Ruth Alscher with three small children. 2. Herman Bauch [no reference] 3. Soloman H. Bauch Lawyer for Pitt Machine Products; where Julius Rosenberg worked. On June 6, 1950, Julius authorized Bauch to empower Bernie Greenglass to sign company checks, telling him that the Rosenbergs were contemplating a trip. 4. Harry Belock One of Morton Sobell’s superior at Reeves Electronics in June 1950 when Sobell fled to Mexico. 5. Dr. George Bernhardt Bernhardt testified at the Rosenbergs trial regarding plans of the Rosenbergs and Morton Sobell to secure travel documents and flee the country, possibly to Russia. -

Freed Cold War Spy Morton Sobel!

Freed Cold War Spy Morton Sobel! QT ANDING before the bar of L' justice in Federal Court here on Thursday, April 5, 1961, a mild-looking man heard Judge Irving R. Kauf- man tell him: "I do not for a moment doubt that you were engaged in espionage activities; however, the evi- dence in the case did not point to any ac- Man tivity on your part in connec- tion with the News atom bomb proj- ect." The •subject and object of these words was Morton Sobell, and sec- onds later he was sentenced to 30 years in prison. Then the judge said, "While it might be gratuitous on my part, I also not, at this point my recommendation against United Press international parole for this defendant." More than 18 years in Then and there the stage continuous custody, was set for one of the most massive, most protracted ef- York on April 11, 1917. At forts ever made to free a Stuyvesant High School he prisoner. met Max Elitcher, who later Yesterday, nearly 18 years Was to be the chief Govern- later, Morton Sobell was ment witness against him at given his release, not because the conspiracy trial. Their of the appeals but because friendship continued through be had served his sentence, City College, where they bath with time off for good be- knew Julius Rosenberg, a havior, fellow student. At the time of his trial on Sobell was graduated from charges of conspiracy to com- City College in 1938 and in mit espionage, Sobell was a 1942 received a master's de- relatively minor figure, over- gree in electrical engineering shadowed by two of his co- from the University of Mich- defendants, Julius and Ethel igan. -

U-M·I University Microfilms International a Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road

Castro's Cuba and Stroessner's Paraguay: A comparison of the totalitarian/authoritarian taxonomy. Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Sondrol, Paul Charles. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 11:08:31 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/185284 INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photogr2,pb and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted.. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this -reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is inciuded in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Biographyelizabethbentley.Pdf

Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet 1 of 284 QUEEN RED SPY Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet 2 of 284 3 of 284 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet RED SPY QUEEN A Biography of ELIZABETH BENTLEY Kathryn S.Olmsted The University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill and London Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 4 of 284 © 2002 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet The University of North Carolina Press All rights reserved Set in Charter, Champion, and Justlefthand types by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Manufactured in the United States of America The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Olmsted, Kathryn S. Red spy queen : a biography of Elizabeth Bentley / by Kathryn S. Olmsted. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-8078-2739-8 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Bentley, Elizabeth. 2. Women communists—United States—Biography. 3. Communism—United States— 1917– 4. Intelligence service—Soviet Union. 5. Espionage—Soviet Union. 6. Informers—United States—Biography. I. Title. hx84.b384 o45 2002 327.1247073'092—dc21 2002002824 0605040302 54321 Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 5 of 284 To 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet my mother, Joane, and the memory of my father, Alvin Olmsted Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet 6 of 284 7 of 284 Contents Preface ix 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet Acknowledgments xiii Chapter 1. -

Cold War Era Spies

H-FedHist C-SPAN 3: Cold War Era Spies Discussion published by David Chambers on Saturday, April 26, 2014 [Ed. note: although the air dates have passed, a recording of the event is still available by following the C-SPAN link below.]"Cold War Era Spies" airs on C-SPAN 3 with papers on Whittaker Chambers, Morton Sobell, Morris Childs, and Julia Brown. Airtime Dates: Apr 27, 2014 @ 6:30pm EDT - C-SPAN 3 Apr 27, 2014 @ 10:30pm EDT - C-SPAN 3 May 03, 2014 @ 10:30am EDT - C-SPAN 3 May 04, 2014 @ 6:30am EDT - C-SPAN 3 To watch online during airtime: http://www.c-span.org/live/?channel=c-span-3 Further details: C-SPAN: http://www.c-span.org/video/?318550-2/cold-war-era-spies SHFG: 2014 Annual Conference of the Society for History in the Federal Government - http://shfg.org/shfg/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/SHFG-2014-Annual-Meeting-Program-3.pdf Program details: The Dueling Loyalties of Cold War Era Spies of the U.S. Government and the Soviet Union Katherine Sibley, Saint Joseph’s University - Chair David Chambers, Independent Historian - “Whittaker Chambers and the Global Network of Great Illegals, 1932-1935” Jason Roberts, Quincy College - “An Examination of the Rosenberg Grand Jury Transcripts” John Fox, Historian, Federal Bureau of Investigation - “The FBI’s Eyes on the Communist World: Morris Childs, Cold War Intelligence and the Sino-Soviet Spilt” Veronica Wilson, University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown - “To Tell All My People”: Race, Representation, and African-American FBI Informant Julia Brown Citation: David Chambers. -

Security and Freedom-That Is Today’S Great Challenge

SECURITYand FREEDOM the GREAT CHALLENGE Thirtieth Annual Report of the American Civil Liberties Union Dedicated to ROGER N. BALDWIN Esecntive Director 1920-1910 JOHN HAYNES HOLMES Chairman of the Board of Directors 1940- 19 T 0 EDWARD A. ROSS Chairman of the National Committee 1940-1950 with Respect, Gratitude and Affection TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION--“A FREE NATION OF FREE PEOPLE” 5 SECURITY AND CIVIL LIBERTIES .,.. 10 A. GENERAL ANTI-SEDITION LBGISLAI‘IVE EFFORTS 10 1. The McCarran Act ,. .,, 10 2. “Little McCarran” Acts 3. The Smith Act .,. ,.,..... ,.. :i 4. House Un-American Activities Committee ,........ .,............ 5. House Lobbying Committee ::, 6. State Investigations 17 B. SKIJRITY AND LOYAL’IY AMONG EMPLOYEES 17 1. Federal Program 2. The McCarthy Charges ::, 3. State and Local Programs; 4. Private Programs’ 22 C. OTHER THREATS TO FREEDOM OF OPINION 25 1. General Free Speech .,,....,,..,.... 2. Radio and Movies ., :: 3. Magazines and Books ..,. .._........... 29 4. Schools and Colleges .._.......... 5. Labor Unions .._...... 6. Aliens .._ .,..... .,.. .._ 7. Conscientious Objection __....,.._.........._.,..,,.......,,........................... D. OTHER THREATS TO DUE PROCESS OF LAW 1. Wiretapping ..,,...., .,..... 2. Bail Cases 3. Picketing of Courts 4. Grand Juries 38 THE FIRST FREEDOM .._............... 39 A. GENERAL FREE EXPRESSION .._.............................. B. LABOR ,,., . .. .. .. .. .. :; C. CENSORSHIP .,,,,.. ,.,... 40 D. RELIGION .,.. 44 DUE PROCESS OF LAW ,. 46 A. WIRETAPPING ,, ., .,,.... ..,...,_ .,, .,... .., .,.. 46 B. FAIR TRIAL .., 48 C. PUNISHMENT ,,... ,, 49 EQUALITY 49 A. MINORITIES ..~... 50 B. STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACTIVITIES .._......... .._...... 53 1. Employment and Education .._ 2. Housing and Public Accommodations :; 3. Voting and Fair Trial .,.... ,... 55 C. PRIVATE ORGANIZATIONS 56 1. Social 56 2. -

HON. HERBERT ZELENKO Ous Progress and Growth

1958 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD- HOUSE 4825 deremployment in ·certain economically· de I veterans; to the Committee on Veterans' H. R. 11519. A bill to authorize the use of pressed areas; to the Committee on Banking Affairs. naval vessels to determine the effect of and Currency. By Mr. MACHROWICZ: newly developed weapons upon such vessels; By Mr. DENT: H. R. 11507. A bill to amend section 37 of to the Committee on Armed Services. H. R. 11497. A bill to amend title n of the Internal Revenue Code of 1954 to equal By Mr. WHITENER: the Social Security Act to inClude Pennsyl ize for all taxpayers the amount which may H. R. 11520. A bill to provide that the Blue vania among the States which may obtain be taken into account in computing there Ridge Parkway shall be toll free; to the social-security coverage, under State agree tirement income credit thereunder; to the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs. ment, for State and local policemen and fire Committee on Ways and Means. By l.\4r. MOORE: men; to the Committee on Ways and Means. By Mr. MILLER of Nebraska: By Mr. FORRESTER: H. R. 11508. A b111 to provide for the con H. R. 11521. A bill to extend for 1 year H. R. 11498. A bill to amend chapter 223 version of surplus grain owned by the Com the authority of the President to enter into of title 18, United States Code, to provide for modity Credit Corporation into industrial trade agreements under section 350 of the the admission of certain evidence; to the alcohol for stockpiling purposes; to the Com Tariff Act of 1930, as amended, and for other purposes; to the Committee on Ways Committee on the Judiciary. -

Helen Sobell .Pdf

Love, Betrayal, and the Cold War: An American Story This is the Accepted version of the following publication Deery, Phillip (2017) Love, Betrayal, and the Cold War: An American Story. American Communist History, 16 (1-2). 65 - 87. ISSN 1474-3892 The publisher’s official version can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14743892.2017.1360630 Note that access to this version may require subscription. Downloaded from VU Research Repository https://vuir.vu.edu.au/34767/ Love, Betrayal and the Cold War: an American story Phillip Deery I wait for your touch to spring into life Your absence is pain and torment and strife (Helen Sobell, “Empty Hours”, 1956) 1 Shall I languish here forgotten On the perjured word of one Or will valiant men and women Cry for justice to be done? (Edith Segal, “Thirty Years: A Ballad for Morton Sobell”, 1959) Introduction This article investigates, for the first time, two decades of political activism by one woman, Helen Sobell. Using previously untapped archives, it reveals how she waged a relentless struggle on behalf of her husband, Morton Sobell. She guaranteed that he did not “languish here forgotten”. Sobell was sentenced in 1951 to thirty years imprisonment after being convicted with Julius and Ethel Rosenberg of conspiracy to commit espionage. This is a story, in part, about how their relationship unfolded through four prisons, eight Supreme Court appeals2 and nearly nineteen years of incarceration. It is also a story of harassment from the state, to which her FBI files abundantly attest. Ultimately, it is a story of political mobilization, stretching from the United States to Europe. -

Table of Contents

Vol. 3, No. 3 Fall 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITOR’S NOTE Enoch Powell’s Other Warning TOQ Editors 3 THE CLASSICS CORNER The Road to National Suicide Enoch Powell 7 ARTICLES Understanding Jewish Influence II: Zionism and the Internal Dynamics of Judaism Kevin MacDonald 15 The Reality of Red Subversion: The Recent Confirmation of Soviet Espionage in America Stephen J. Sniegoski 45 BOOK REVIEWS Mexifornia: A State of Becoming Reviewed by John Attarian 71 The South Under Siege 1830-2000: A History of the Relations between the North and the South Reviewed by William Scott 79 DNA: The Secret of Life Reviewed by Leslie Jones 87 The Scientific Study of Intelligence: Tribute to Arthur R. Jensen Reviewed by Kevin Lamb 93 Editors 100 Editorial Advisory Board 101 The Occidental Quarterly (ISSN 1539-3925), a journal of Western thought and opinion, is published by The Charles Martel Society four times annually in the Fall, Winter, Spring, and Summer. Unsolicited manuscripts from contributing authors should be submitted to the editorial department address: P.O. Box 695, Mt. Airy, MD 21771. Style sheets are available upon request. Subscriptions in the U.S. are $40 annually, $78 for two years, and $114 for three years; subscription rates for Canada $45 (first year), $88 (two years), and $129 (three years); European subscription rates: $60 (first year), $118 (two years) $174 (three years). All subscriptions including additional inquiries or subscription problems should be mailed to the subscription department: P.O. Box 3462 Augusta, GA 30914. Back issues are $10 per issue. WASHINGTON SUMMIT PUBLISHERS Classic Reprints :¤¤Contemporay Works WASHINGTON SUMMIT PUBLISHERS (WSP) now offers contemporary works and classic reprints ANTHROPOLOGY (which include recently abridged versions and texts drawn from earlier works) in the social EVOLUTION sciences with particular emphasis on anthropology, evolution and genetics, philosophy, politics and GENETICS current events, and psychology. -

Requests Comments & Opinions Re RV Latour Article on SL-1 Reactor

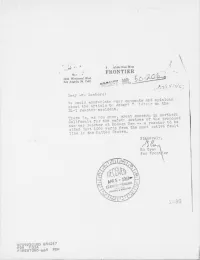

- . j . ,. - , , . ; . - - t , d ,, _,. y a 3 _ , - .- - . -. m 2. ~#- >~s ?~ '.< * i a' . q - . t , -J . : 1 .. ) | ' |I 1 l 1 q J t ., , '~ ( . f"* L. Atsenewwa.< ' ._ a " ; FRONTIER . , ~ . , . .. \ ust westwood Blvd. Los Angeles 24, Calif. M\ '' D*'}Q .i , '&ff b . * J A ,6 W o j Dear Dr. Seaborg: We would appreciate *our comments and' opinions about the article by Robert V. Latonr on the SL-1 reactor accident. ' There is, as vou know, great concern in northern l California for the safety devices of the proposed { nucl. ear reactor at Bodega Bay -- a reactoractive tofault be { sited just 1000 yards from the most i line in the United States, Si cerely, *T { ,; i Ed Gray j 'for Frontter t- to 8 0) t =S {\ = - APR3- 3 5. - tr gett=i&*3 ,n, i c sw T;tbma b h N - 2480 . , '5709230183 851217 PDR FOIA. PDR < FIRESTOBS-665 , .1 . +~ om :m m , - : nk,. _ , . - . .- .. L FRONT ER THE VOICE OF THE NEW WEST APRIL 1963 35 CENTS BERTRAND RUSSELL The Myth of American Freedom Do You Want Somebody Killed? / The Boom in Land Frauds / Hang Your Clothes on a Hickory Limb l From the New Inn to the Bear's Lair: Oxford and Berkeley - . Plus Reviews of Upton Sinclair's Autobiography and an angry James Baldwin's The Fire Next Time 4 . _ _ - _ . - - - - _ _ . _ . _ . _ . _ _ _ . _ . ,, ... _ ,__ _ i , u. _ ~ . .. ; * , . , the electior; of a Birch-cupported candi- . date as president of the organization. THIS MONTH The sensible element in the California Young Republicans was not so lucky, site. -

A Dramaturgical Analysis of the Rosenberg Case. Kenneth C

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1988 A Judicial Decision Under Pressure: A Dramaturgical Analysis of the Rosenberg Case. Kenneth C. Petress Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Petress, Kenneth C., "A Judicial Decision Under Pressure: A Dramaturgical Analysis of the Rosenberg Case." (1988). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4531. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4531 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. -

Ethel and Julius Rosenberg's Trial Atossa M

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 53 | Issue 4 2003 Government against Two: Ethel and Julius Rosenberg's Trial Atossa M. Alavi Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Atossa M. Alavi, Government against Two: Ethel and Julius Rosenberg's Trial, 53 Case W. Res. L. Rev. 1057 (2003) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol53/iss4/17 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE GOVERNMENT AGAINST Two: ETHEL AND JULIUS ROSENBERG'S TRIAL It is important that the country be protected against the nefarious plans of spies who would destroy us. It is also important that before we allow human lives to be snuffed out we be sure - emphatically sure - that we act within the law. Justice Douglas' In January 2003 as the United States was preparing to invade Iraq, the two-week trial of accused spy Brian Patrick Regan2 came to a close. Regan was arrested in August 2001 in Dulles Interna- tional Airport on charges of attempting to sell classified military data to Iraq, Libya, and China. At the time of his arrest, he was found to have hidden in his shoes encrypted coordinates of a sur- face-to-air missile site in the no-fly zone in northern Iraq where U.S.