01C — Page 1-43 — Keeping Liberty Alive Through Covid-19 and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

01A — Page 1-21 — the SA Pink Vote (13.08.2021)

August 2021 Published by the South African Institute of Race Relations (IRR) P O Box 291722, Melville, Johannesburg, 2109 South Africa Telephone: (011) 482–7221 © South African Institute of Race Relations ISSN: 2311-7591 Members of the Media are free to reprint or report information, either in whole or in part, contained in this publication on the strict understanding that the South African Institute of Race Relations is acknowledged. Otherwise no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronical, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. While the IRR makes all reasonable efforts to publish accurate information and bona fi de expression of opinion, it does not give any warranties as to the accuracy and completeness of the information provided. The use of such information by any party shall be entirely at such party’s own risk and the IRR accepts no liability arising out of such use. Editor-in-chief: Frans Cronje Authors: Gerbrandt van Heerden Typesetter: Martin Matsokotere Cover design by Alex Weiss TABLE OF CONTENTS THE SA PINK VOTE . .4 Introduction . 4 Purpose of the study . 5 Why is it important to monitor the Pink Vote? . 5 Th e track record of South Africa’s political parties in terms of LGBTQ rights . 7 African National Congress (ANC). 7 Democratic Alliance (DA) . 10 Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) . 12 Opinion poll results . 14 Key Findings . 15 South African LGBTQ voters are highly likely to turn out at the ballot box . -

Download the Full GTC ONE Minute Brief

Equity | Currencies & Commodities | Corporate & Global Economic News | Technical Snapshot | Economic Calendar 25 June 2019 Economic and political news Key indices Former Chief Financial Officer (CFO) of the Public Investment As at 24 1 Day 1 D % WTD % MTD % Prev. month YTD % Corporation (PIC), Matshepo More, has dismissed allegations of June 2019 Chg Chg Chg Chg % Chg Chg JSE All Share impropriety and victimisation levelled against her by the PIC 58756.01 -185.46 -0.31 -0.31 5.58 -4.92 11.41 commission and PIC employees. (ZAR) Public Protector, Busisiwe Mkhwebane, has denied news reports that JSE Top 40 (ZAR) 52760.96 -141.92 -0.27 -0.27 6.40 -5.14 12.91 investigations are underway on fresh money-laundering allegations FTSE 100 (GBP) 7416.69 9.19 0.12 0.12 3.56 -3.46 10.23 against President, Cyril Ramaphosa. DAX 30 (EUR) 12274.57 -65.35 -0.53 -0.53 4.67 -5.00 16.25 Citadel Portfolio Manager, Mike van der Westhuizen, has criticised CAC 40 (EUR) 5521.71 -6.62 -0.12 -0.12 6.03 -6.78 16.72 President, Cyril Ramaphosa’s Eskom bailout plan and stated that it could S&P 500 (USD) 2945.35 -5.11 -0.17 -0.17 7.02 -6.58 17.49 pose a risk to South Africa’s fiscal debt. Nasdaq 8005.70 -26.01 -0.32 -0.32 7.41 -7.93 20.65 According to a news report, Natasha Mazzone is the front runner to Composite (USD) replace Democratic Alliance (DA) chief whip, John Steenhuisen, who is DJIA (USD) 26727.54 8.41 0.03 0.03 7.71 -6.69 14.58 MSCI Emerging set to become the party's federal executive chairperson. -

EASTERN CAPE NARL 2014 (Approved by the Federal Executive)

EASTERN CAPE NARL 2014 (Approved by the Federal Executive) Rank Name 1 Andrew (Andrew Whitfield) 2 Nosimo (Nosimo Balindlela) 3 Kevin (Kevin Mileham) 4 Terri Stander 5 Annette Steyn 6 Annette (Annette Lovemore) 7 Confidential Candidate 8 Yusuf (Yusuf Cassim) 9 Malcolm (Malcolm Figg) 10 Elza (Elizabeth van Lingen) 11 Gustav (Gustav Rautenbach) 12 Ntombenhle (Rulumeni Ntombenhle) 13 Petrus (Petrus Johannes de WET) 14 Bobby Cekisani 15 Advocate Tlali ( Phoka Tlali) EASTERN CAPE PLEG 2014 (Approved by the Federal Executive) Rank Name 1 Athol (Roland Trollip) 2 Vesh (Veliswa Mvenya) 3 Bobby (Robert Stevenson) 4 Edmund (Peter Edmund Van Vuuren) 5 Vicky (Vicky Knoetze) 6 Ross (Ross Purdon) 7 Lionel (Lionel Lindoor) 8 Kobus (Jacobus Petrus Johhanes Botha) 9 Celeste (Celeste Barker) 10 Dorah (Dorah Nokonwaba Matikinca) 11 Karen (Karen Smith) 12 Dacre (Dacre Haddon) 13 John (John Cupido) 14 Goniwe (Thabisa Goniwe Mafanya) 15 Rene (Rene Oosthuizen) 16 Marshall (Marshall Von Buchenroder) 17 Renaldo (Renaldo Gouws) 18 Bev (Beverley-Anne Wood) 19 Danny (Daniel Benson) 20 Zuko (Prince-Phillip Zuko Mandile) 21 Penny (Penelope Phillipa Naidoo) FREE STATE NARL 2014 (as approved by the Federal Executive) Rank Name 1 Patricia (Semakaleng Patricia Kopane) 2 Annelie Lotriet 3 Werner (Werner Horn) 4 David (David Christie Ross) 5 Nomsa (Nomsa Innocencia Tarabella Marchesi) 6 George (George Michalakis) 7 Thobeka (Veronica Ndlebe-September) 8 Darryl (Darryl Worth) 9 Hardie (Benhardus Jacobus Viviers) 10 Sandra (Sandra Botha) 11 CJ (Christian Steyl) 12 Johan (Johannes -

African National Congress NATIONAL to NATIONAL LIST 1. ZUMA Jacob

African National Congress NATIONAL TO NATIONAL LIST 1. ZUMA Jacob Gedleyihlekisa 2. MOTLANTHE Kgalema Petrus 3. MBETE Baleka 4. MANUEL Trevor Andrew 5. MANDELA Nomzamo Winfred 6. DLAMINI-ZUMA Nkosazana 7. RADEBE Jeffery Thamsanqa 8. SISULU Lindiwe Noceba 9. NZIMANDE Bonginkosi Emmanuel 10. PANDOR Grace Naledi Mandisa 11. MBALULA Fikile April 12. NQAKULA Nosiviwe Noluthando 13. SKWEYIYA Zola Sidney Themba 14. ROUTLEDGE Nozizwe Charlotte 15. MTHETHWA Nkosinathi 16. DLAMINI Bathabile Olive 17. JORDAN Zweledinga Pallo 18. MOTSHEKGA Matsie Angelina 19. GIGABA Knowledge Malusi Nkanyezi 20. HOGAN Barbara Anne 21. SHICEKA Sicelo 22. MFEKETO Nomaindiya Cathleen 23. MAKHENKESI Makhenkesi Arnold 24. TSHABALALA- MSIMANG Mantombazana Edmie 25. RAMATHLODI Ngoako Abel 26. MABUDAFHASI Thizwilondi Rejoyce 27. GODOGWANA Enoch 28. HENDRICKS Lindiwe 29. CHARLES Nqakula 30. SHABANGU Susan 31. SEXWALE Tokyo Mosima Gabriel 32. XINGWANA Lulama Marytheresa 33. NYANDA Siphiwe 34. SONJICA Buyelwa Patience 35. NDEBELE Joel Sibusiso 36. YENGENI Lumka Elizabeth 37. CRONIN Jeremy Patrick 38. NKOANA- MASHABANE Maite Emily 39. SISULU Max Vuyisile 40. VAN DER MERWE Susan Comber 41. HOLOMISA Sango Patekile 42. PETERS Elizabeth Dipuo 43. MOTSHEKGA Mathole Serofo 44. ZULU Lindiwe Daphne 45. CHABANE Ohm Collins 46. SIBIYA Noluthando Agatha 47. HANEKOM Derek Andre` 48. BOGOPANE-ZULU Hendrietta Ipeleng 49. MPAHLWA Mandisi Bongani Mabuto 50. TOBIAS Thandi Vivian 51. MOTSOALEDI Pakishe Aaron 52. MOLEWA Bomo Edana Edith 53. PHAAHLA Matume Joseph 54. PULE Dina Deliwe 55. MDLADLANA Membathisi Mphumzi Shepherd 56. DLULANE Beauty Nomvuzo 57. MANAMELA Kgwaridi Buti 58. MOLOI-MOROPA Joyce Clementine 59. EBRAHIM Ebrahim Ismail 60. MAHLANGU-NKABINDE Gwendoline Lindiwe 61. NJIKELANA Sisa James 62. HAJAIJ Fatima 63. -

Woman Held for Filming Maid's Fall from Window

SUBSCRIPTION SATURDAY, APRIL 1, 2017 RAJAB 4, 1438 AH No: 17185 Woman held for filming maid’s fall from window Min 20º 150 Fils Employer had hired runaway maid from illegal office Max 31º By Hanan Al-Saadoun and Agencies the incident itself is not a crime, but he said the Ajmi returns to Kuwait employer could be charged with negligence and KUWAIT: Police have detained a woman for film- failure to offer help. Investigations are currently KUWAIT: Saad Al-Ajmi, former ing her Ethiopian maid falling from the seventh ongoing to determine whether the case is a suicide spokesman of the opposition Popular floor in an apparent suicide attempt without try- attempt, an accident that happened while the maid Action Movement, returned home to ing to rescue her, media and a rights group said was working, or a case of attempted homicide and Kuwait late on Thursday. Ajmi, who yesterday. The Kuwaiti woman filmed her maid libel. “The law says that any person who fails to help was deported to Saudi Arabia after land on a metal awning and survive, then posted someone else who poses a grave danger to himself his citizenship was revoked, returned the incident on social media. The criminal inves- or his possessions will be punished with a maximum through the Nuwaiseeb border outlet tigation police referred the employer to the pros- three months in jail and/or a fine,” Ruwaih said. after two years in exile. An elated ecution over failing to help the victim. The The 12-second video shows the maid hanging Ajmi thanked HH the Amir Sheikh Saad Al-Ajmi hugs his children upon Kuwait Society for Human Rights yesterday outside the building, with one hand tightly gripping Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah, his return home late on Thursday. -

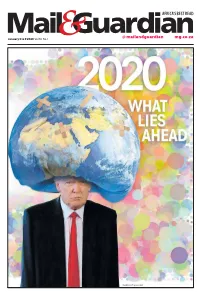

Africa's Best Read

AFRICA’S BEST READ January 3 to 9 2020 Vol 36 No 1 @ mailandguardian mg.co.za Illustration: Francois Smit 2 Mail & Guardian January 3 to 9 2020 Act or witness IN BRIEF – THE NEWS YOU MIGHT HAVE MISSED Time called on Zulu king’s trust civilisation’s fall The end appears to be nigh for the Ingonyama Trust, which controls more than three million A decade ago, it seemed that the climate hectares of land in KwaZulu-Natal on behalf crisis was something to be talked about of King Goodwill Zwelithini, after the govern- in the future tense: a problem for the next ment announced it will accept the recommen- generation. dations of the presidential high-level panel on The science was settled on what was land reform to review the trust’s operations or causing the world to heat — human emis- repeal the legislation. sions of greenhouse gases. That impact Minister of Agriculture, Land Reform and had also been largely sketched out. More Rural Development Thoko Didiza announced heat, less predictable rain and a collapse the decision to accept the recommendations in the ecosystems that support life and and deal with barriers to land ownership human activities such as agriculture. on land controlled by amakhosi as part of a But politicians had failed to join the dots package of reforms concerned with rural land and take action. In 2009, international cli- tenure. mate negotiations in Copenhagen failed. She said rural land tenure was an “immedi- Other events regarded as more important ate” challenge which “must be addressed.” were happening. -

Zuma's Cabinet Reshuffles

Zuma's cabinet reshuffles... The Star - 14 Feb 2018 Switch View: Text | Image | PDF Zuma's cabinet reshuffles... Musical chairs reach a climax with midnight shakeup LOYISO SIDIMBA [email protected] HIS FIRST CABINET OCTOBER 2010 Communications minister Siphiwe Nyanda replaced by Roy Padayachie. His deputy would be Obed Bapela. Public works minister Geoff Doidge replaced by Gwen MahlanguNkabinde. Women, children and people with disabilities minister Noluthando MayendeSibiya replaced by Lulu Xingwana. Labour minister Membathisi Mdladlana replaced by Mildred Oliphant. Water and environmental affairs minister Buyelwa Sonjica replaced by Edna Molewa. Public service and administration minister Richard Baloyi replaced by Ayanda Dlodlo. Public enterprises minister Barbara Hogan replaced by Malusi Gigaba. His deputy became Ben Martins. Sport and recreation minister Makhenkesi Stofile replaced by Fikile Mbalula. Arts and culture minister Lulu Xingwana replaced by Paul Mashatile. Social development minister Edna Molewa replaced by Bathabile Dlamini. OCTOBER 2011 Public works minister Gwen MahlanguNkabinde and her cooperative governance and traditional affairs counterpart Sicelo Shiceka are axed while national police commissioner Bheki Cele is suspended. JUNE 2012 Sbu Ndebele and Jeremy Cronin are moved from their portfolios as minister and deputy minister of transport respectively Deputy higher education and training minister Hlengiwe Mkhize becomes deputy economic development minister, replacing Enoch Godongwana. Defence minister Lindiwe Sisulu moves to the Public Service and Administration Department, replacing the late Roy Padayachie, while Nosiviwe MapisaNqakula moves to defence. Sindisiwe Chikunga appointed deputy transport minister, with Mduduzi Manana becoming deputy higher education and training minister. JULY 2013 Communications minister Dina Pule is fired and replaced with former cooperative government and traditional affairs deputy minister Yunus Carrim. -

Who's Feeding the PP Her Info? • Who's Paying For

AFRICA’S BEST READ July 26 to August 1 2019 Vol 35 No 30 @mailandguardian mg.co.za Protect us from this mess OWho’s feeding the PP her info? OWho’s paying for CR? OWho really has the power? Pages 3, 4, 5, 8 & 23 PHOTO: MADELENE CRONJÉ 2 Mail & Guardian July 26 to August 1 2019 INSIDE IN BRIEF NEWS Little red trolls stick ANC on horns of protector dilemma it to Hanekom NUMBERS OF THE WEEK One opposition party want to keep her and In a revelation that The estimated the other lose her, and the ANC is divided 3 was a shock to eve- death toll from The percentage of the ryone except former Hurricane Maria, Who breathes the worst air in SA? president Jacob South African Reserve 4which645 devastated Puerto Rico in Sep- Jo’burgers do! 6 Zuma — who sees Bank's legal fees public tember 2017. This week thousands of spies lurking every- protector Busisiwe Puerto Rican protesters took to the EFF off to court to support protector where at the best of Mkhwebane has been The party has applied to join the case 8 times — it emerged this 15% streets demanding the resignation of ordered to pay out of her past week that ANC parliamentarian and Governor Ricardo Rosselló over a tranche own pocket by the Constitutional Court Deviations dodge due process former Cabinet minister Derek Hanekom of leaked chat messages containing a The attorney general has found that plotted with the Economic Freedom Fighters joke about the dead bodies of the municipalities are making use of a process to bring down Zuma. -

Covid-19 Regulatory Update 21Apr2020

COMPILED BY LEXINFO CC Tel 082 690 8890 | 084 559 2847 Email: [email protected] Fax: 086 589 3696 PO Box 36216, Glosderry, 7702 http://www.lexinfo.co.za Covid-19 Regulatory Update 21 April 2020 Covid-19 related guidelines and regulations: https://www.gov.za/coronavirus/guidelines. Covid-19 Directives and notices relating to legal practitioners: http://www.derebus.org.za/directives-covid-19/ / https://lpc.org.za/ CONTENTS AGRICULTURE ........................................................................................................................... 2 CONFIRMED CASES .................................................................................................................. 2 CRIMINAL LAW AND PROCEDURE ........................................................................................... 2 EMPLOYMENT LAW ................................................................................................................... 3 FINANCIAL LAW ......................................................................................................................... 3 LOCKDOWN REGULATIONS ..................................................................................................... 3 PUBLIC SERVICES ..................................................................................................................... 4 SAFETY AND SECURITY ........................................................................................................... 4 STATISTICS ............................................................................................................................... -

Budget Vote Budget Vote

DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS & COOPERATION Budget BUDGET VOTE BUDGET VOTE Extracts from the Freedom Charter Contents Adopted at the Congress of the People, Kliptown, on 26 June 1955 WE, THE PEOPLE OF SOUTH AFRICA, declare for all our country and the world Address by the Minister of International Relations and Cooperation, to know: Ms Maite Nkoana-Mashabane, to the National Assembly on the occasion • that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white, and that no government can justly claim authority unless it is based on the will of all the of the Budget Vote 1 – 27 people; • that our people have been robbed of their birthright to land, liberty and peace by Reply to the Budget Vote by the Deputy Minister of International Relations a form of government founded on injustice and inequality; • that our country will never be prosperous or free until all our people live in and Cooperation, Mr Ebrahim Ismail Ebrahim, to the National Assembly 29 – 37 brotherhood, enjoying equal rights and opportunities; • that only a democratic state, based on the will of all the people, can secure to all Reply to the Budget Vote by the Deputy Minister of International Relations their birthright without distinction of colour, race, sex or belief; • And therefore, we, the people of South Africa, black and white together equals, and Cooperation, Ms Sue van der Merwe, to the National Assembly 39 – 49 countrymen and brothers adopt this Freedom Charter; • And we pledge ourselves to strive together, sparing neither strength nor courage, until the democratic changes here set out have been won. -

THE NEW CABINET: ABLE to DELIVER OR the SAME OLD SAME OLD? by Theuns Eloff: Chair, FW De Klerk Foundation Board of Advisors

THE NEW CABINET: ABLE TO DELIVER OR THE SAME OLD SAME OLD? By Theuns Eloff: Chair, FW de Klerk Foundation Board of Advisors The excitement and disappointment (in some quarters) regarding the appointment of President Cyril Ramaphosa’s Cabinet has settled. A number of articles have already been written about the Cabinet and its strong points, weak points, old members, and new recruits. The question remains: can the new Cabinet deliver on the President’s promises? It is essential to remember that the most fundamental change to the new Cabinet is the chairman. How President Ramaphosa will lead - and what he prioritises - will distinguish his Cabinet from that of its predecessor. In addition, what is new is the support he will have. It is now generally understood that the choice of Ministers and deputies was a product of intense behind-the-scenes negotiations with various stakeholders. In the end, of the 28 Ministers, only five are known-Zuma supporters (including Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, who in the recent past has actually become supportive of the Ramaphosa cause). This implies that Ramaphosa has more than 80% of his Cabinet not in opposition to him or his plans. Even though the number of Deputy Ministers was inflated beyond initial plans, it is clear that at most, 12 of the 34 deputies were products of compromise with the Zuptoid faction. This gives Ramaphosa 75% support in the entire group and even more in the actual Cabinet of 28. That is a strong start, especially when one considers the potency of various factions and stakeholders in the ANC alliance. -

Cabinet Changes 2014-18

SOUTH AFRICA EXECUTIVE 2014 – 2019 (FIFTH ADMINISTRATION) PORTFOLIO 25 MAY 2014 22 SEPT 2015 9 DEC 2015 13 DEC 2015 30 MARCH 2017 17 OCT 2017 27 FEB 2018 22 NOV 2018 Agriculture, MINISTER Mr Senzeni Mr Senzeni Mr Senzeni Mr Senzeni Mr Senzeni Mr Senzeni Mr Senzeni Mr Senzeni Forestry & Zokwana Zokwana Zokwana Zokwana Zokwana Zokwana Zokwana Zokwana Fisheries DEPUTY Mr Bheki Cele Mr Bheki Cele Mr Bheki Cele Mr Bheki Cele Mr Bheki Cele Mr Bheki Cele Mr Sfiso Mr Sfiso MINISTER Buthelezi Buthelezi Arts And MINISTER Mr Nathi Mr Nathi Mr Nathi Mr Nathi Mr Nathi Mr Nathi Mr Nathi Mr Nathi Culture Mthethwa Mthethwa Mthethwa Mthethwa Mthethwa Mthethwa Mthethwa Mthethwa DEPUTY Ms R Ms R Ms R Ms R Ms Maggie Ms Maggie Ms Maggie Ms Maggie MINISTER Mabudafhasi Mabudafhasi Mabudafhasi Mabudafhasi Sotyu Sotyu Sotyu Sotyu Basic Education MINISTER Ms Angie Ms Angie Ms Angie Ms Angie Ms Angie Ms Angie Ms Angie Ms Angie Motshekga Motshekga Motshekga Motshekga Motshekga Motshekga Motshekga Motshekga DEPUTY Mr Enver Mr Enver Mr Enver Mr Enver Mr Enver Surty Mr Enver Surty Mr Enver Mr Enver MINISTER Surty Surty Surty Surty Surty Surty Communicatio MINISTER Ms Faith Ms Faith Ms Faith Ms Faith Ms Ayanda Ms Mmamoloko Ms Nomvula Ms Stella ns Muthambi Muthambi Muthambi Muthambi Dlodlo Kubayi Mokoyane Ndabeni- Abrahams DEPUTY Ms Stella Ms Stella Ms Stella Ms Stella Ms Tandi Ms Tandi Ms Pinky Ms Pinky MINISTER Ndabeni- Ndabeni- Ndabeni- Ndabeni- Mahambehlala Mahambehlala Kekana Kekana Abrahams Abrahams Abrahams Abrahams Cooperative MINISTER Mr Pravin Mr Pravin Mr