Full Issue, Number 50, Fall 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Dakota Training in Healthcare

SOUTH DAKOTA TRAINING IN HEALTHCARE HEALTH CARE MANAGER ADDICTION STUDIES Western Dakota Technical, Rapid City The University of South Dakota, Vermillion HEALTH CARE/SERVICES ADMINISTRATOR ATHLETIC TRAINER The University of South Dakota, Vermillion Augustana University, Sioux Falls Presentation College, Aberdeen Dakota Wesleyan University, Mitchell Presentation College, Aberdeen HEALTH INFORMATION ADMINISTRATOR South Dakota State University, Brookings Dakota State University, Madison Dakota State University, Online Option AUDIOLOGIST The University of South Dakota, Vermillion HEALTH INFORMATION TECHNOLOGIST Dakota State University, Madison BIOMEDICAL ENGINEER Dakota State University, Online Option South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, Rapid City Dakota State University, University Center, Sioux Falls The University of South Dakota, Vermillion The Right Turn, Inc. (online) CERTIFIED NURSING ASSISTANT HEALTH SCIENCES Training Provided Locally. Contact your local healthcare Presentation College, Aberdeen provider. The University of South Dakota, Vermillion CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGIST INVASIVE CARDIOVASCULAR TECHNICIAN The University of South Dakota, Vermillion Southeast Technical Institute, Sioux Falls COUNSELOR MASSAGE THERAPIST South Dakota State University, Brookings Headlines Academy, Rapid City The University of South Dakota, Vermillion MEDICAL ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT/SERVICES DENTAL ASSISTANT The Right Turn, Inc. (online) Lake Area Technical Institute, Watertown Lake Area Technical Institute, E-Degree, Watertown MEDICAL ASSISTANT -

Roster of Graduates

ROSTER OF GRADUATES BACHELOR OF ARTS Aliyah Rose Abdulrahman, Worthington, MN Taylor Ann Beagle, Lead, SD Anna Elizabeth Boyens, Sioux Falls, SD Spanish, All-Grades Education Biology Biology, Spanish Magna Cum Laude Summa Cum Laude Magna Cum Laude, Civitas Honors Ayida Mohamed Abdurahman, Sioux Falls, SD Betab Belihu, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Ryan Wade Bradberry, Dallas, TX Computer Science/Software Engineering Computer Science/Software Engineering Interdisciplinary Studies Grayce Kay Adler, Lake City, MN Sarah Jane Bell, Sioux Falls, SD Caryn Elizabeth Brakke, Pierre, SD Exercise Science German, All-Grades Education Chemistry Magna Cum Laude, Civitas Honors Mason Allen Ahlers, Watertown, SD Cassondra Bramstedt, Viroqua, WI Biology Blake Jeffrey Bendt, Rapid City, SD Psychology Accounting, Business Administration Mariah Hope Aker, Chanhassen, MN Kaylee Jo Braun, Mina, SD Elementary Education Abigail Lillian Benson, Jackson, MN Biology Cum Laude Business Administration, Accounting Magna Cum Laude Madyson RaeAnn Brown, Willmar, MN Makenna Rose Allen, Mankato, MN Communication Disorders Government/International Affairs Michelle Kay Benson, Owatonna, MN Biology Tanner Sisson Brown, Sioux Falls, SD Skylar Everest Allen, Irvine, CA Magna Cum Laude Business Administration Psychology, Religion Sarah Jean Benson, Chester, SD Christopher Joseph Budde, Albany, MN Luca Rachuonyo Amayo, Nairobi, Kenya English, Secondary Education History, Secondary Education Government/International Affairs Summa Cum Laude Mintesnot Bireda, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Dagny -

CHART A: INFORMATION SOURCE Social Media 10% Faculty Or Staff 6%

After Augustana: Post-Graduation Career Outcomes Report for the Class of 2019 Billie Streufert | Student Success Center The numbers are in — and they speak for themselves. Augustana’s liberal arts degree prepares graduates for success in a variety of careers. The Student Success Center, in collaboration with the Office of Assessment, presents the following data on undergraduate alumni using standards set by the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE).1 Data includes the activities within six months of graduation of individuals who completed a baccalaureate degree in the 2018-2019 academic year (Summer 2018, Fall 2018 or Spring 2019). Augustana contacted these alumni via surveys, emails, phone calls, and social media to determine their post-graduation activities. The Success Center continues to gather information graduates self-reported to faculty, academic advisors, or coaches. Respondents select one post- graduation activity category: working full-time, working part-time, further education or study, military service, volunteering full-time (e.g., Peace Corps, AmeriCorps, mission work), other commitments (e.g., family, moving, travel, etc.), or looking for work. Augustana obtained information on 91% of these graduates, which exceeds the minimum NACE knowledge rate by 26%.2 Sources of information are identified below in Chart A. CHART A: INFORMATION SOURCE Social Media 10% Faculty or Staff 6% Survey 57% SSC Outreach 27% Outcomes Summary Data from the Class of 2019 once again demonstrates Augustana’s ability to offer an education of enduring worth. Of the respondents who provided information, 99% were employed (part-time or full-time) in their major or chosen field and 98% achieved a positive career outcome (e.g., continuing their education, working, serving in the military, or volunteering).3 Each graduate was only counted once in this aggregate statistic. -

Dear Augustana College (Aka University) Alum of 1977! February, 2017

Dear Augustana College (aka University) Alum of 1977! February, 2017 Hello friends! I never seem to have time to write anything when the deadline for publication is due, and here is that time again, but this time, I’m putting together some thoughts fast! Brian and I (class of 1977) have been Augustana Association representatives from Nebraska the last number of years. This is a wonderful day at Augustana the first Friday of December, as we get to see and hear firsthand the current status. We got in a little visit to the Froiland Science Complex (must-see!) and brought some treats to share with Doc and Phyl Krueger that afternoon. We’re so grateful for all those fine professors we had who taught us so very much. It’s most gratifying to be able to spend time with them today and tell them how grateful we are for their hard work and fine teaching! Augie continues to be a wonderful place where such great learning takes place, and we are most proud that such great things are happening. I would encourage each of you to find some time to visit and see for yourself. This fall will be the 40th anniversary celebration of our graduation! There are annual homecoming events to which we’ll be invited. Bob Boyce has created a Facebook Augie Class of 1977 page—40th Year Reunion, Augustana University, Sioux Falls. The main purpose is to determine a time when we can gather and enjoy fellowship together, so please check it out and share your thoughts: https://www.facebook.com/groups/1838912949660216/ Meanwhile, here are links to some highlights. -

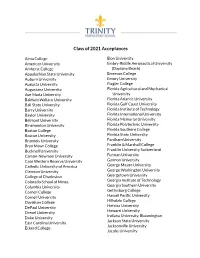

Class of 2021 Acceptances

Class of 2021 Acceptances Alma College Elon University American University Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Amherst College (Daytona Beach) Appalachian State University Emerson College Auburn University Emory University Augusta University Flagler College Augustana University Florida Agricultural and Mechanical Ave Maria University University Baldwin Wallace University Florida Atlantic University Ball State University Florida Gulf Coast University Barry University Florida Institute of Technology Baylor University Florida International University Belmont University Florida Memorial University Binghamton University Florida Polytechnic University Boston College Florida Southern College Boston University Florida State University Brandeis University Fordham University Bryn Mawr College Franklin & Marshall College Bucknell University Franklin University Switzerland Carson-Newman University Furman University Case Western Reserve University Gannon University Catholic University of America George Mason University Clemson University George Washington University College of Charleston Georgetown University Colorado School of Mines Georgia Institute of Technology Columbia University Georgia Southern University Cornell College Gettysburg College Cornell University Hawaii Pacific University Davidson College Hillsdale College DePaul University Hofstra University Howard University Drexel University Indiana University, Bloomington Duke University Jackson State University East Carolina University Jacksonville University Eckerd College Jacobs University -

Member Colleges & Universities

Bringing Colleges & Students Together SAGESholars® Member Colleges & Universities It Is Our Privilege To Partner With 427 Private Colleges & Universities April 2nd, 2021 Alabama Emmanuel College Huntington University Maryland Institute College of Art Faulkner University Morris Brown Indiana Institute of Technology Mount St. Mary’s University Stillman College Oglethorpe University Indiana Wesleyan University Stevenson University Arizona Point University Manchester University Washington Adventist University Benedictine University at Mesa Reinhardt University Marian University Massachusetts Embry-Riddle Aeronautical Savannah College of Art & Design Oakland City University Anna Maria College University - AZ Shorter University Saint Mary’s College Bentley University Grand Canyon University Toccoa Falls College Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College Clark University Prescott College Wesleyan College Taylor University Dean College Arkansas Young Harris College Trine University Eastern Nazarene College Harding University Hawaii University of Evansville Endicott College Lyon College Chaminade University of Honolulu University of Indianapolis Gordon College Ouachita Baptist University Idaho Valparaiso University Lasell University University of the Ozarks Northwest Nazarene University Wabash College Nichols College California Illinois Iowa Northeast Maritime Institute Alliant International University Benedictine University Briar Cliff University Springfield College Azusa Pacific University Blackburn College Buena Vista University Suffolk University California -

Annual Report 2017 Dialogue in Divided Societies

Annual Report 2017 Dialogue in Divided Societies Presented by It is a great honor for Augsburg University to be host and home to the Nobel Peace Prize Forum in Minneapolis with our many organizing partners, including the University of Minnesota. On behalf of all the student and faculty attendees, thank you for supporting us in the work of sending out into the world better informed and equipped peacemakers. — Paul C. Pribbenow, Augsburg University President GREETINGS FROM THE PROGRAM DIRECTOR reetings from the office of the Nobel Peace Prize Forum, hosted at Augsburg University. It has been a momentous year, with the return of the Forum to the Augsburg campus as we marked our transition from a college to a university. This year’s return to campus and the Cedar-Riverside community refocused on both student and community involvement, with an increased emphasis on action and engagement with ongoing peacemaking efforts. The Grepresentatives of the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet—our honored laureates this year—were gracious, wise, and good-humored. It was easy to see how they were able to bring together the fractious parties in Tunisia to foster a pluralistic democratic system during a time of serious risks of social fragmentation and violence. More than 1,700 people attended the 2017 Forum, triple the level from 2016, and this year’s participants engaged with a rich array of accomplished guests and speakers. We were pleased to host the Secretary of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, Olav Njølstad, and appreciated his willingness to participate during the busy weeks leading up to the October 6 announcement of the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize recipient. -

Class of 1971 Viking Update

ST. OLAF COLLEGE Class of 1971 – PRESENTS – The Viking Update in celebration of its 50th Reunion Autobiographies and Remembrances stolaf.edu 1520 St. Olaf Avenue, Northfield, MN 55057 Advancement Division 800-776-6523 Student Project Manager Genevieve Hoover ’22 Student Editors Teresa Fawsett ’22 Grace Klinefelter ’23 Student Designers Inna Sahakyan ’23 50th Reunion Staff Members Ellen Draeger Cattadoris ’07 Olivia Snover ’19 Cheri Floren Printing Park Printing Inc., Minneapolis, MN Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in the Viking Update are those of the individual alumni and do not reflect the official policy or position of St. Olaf College. Biographies are not fact-checked for accuracy. 4 CLASS OF 1971 REUNION COMMITTEE REUNION CO-CHAIRS Sally Olson Bracken and Ted Johnson COMMUNICATIONS GIFT COMMITTEE PROGRAM COMMITTEE COMMITTEE CO-CHAIRS CO-CHAIRS CO-CHAIRS Jane Ranzenberger Goldstein Susan Myhre Hayes Natalie Larsen Gehringer Kris Yung Walseth Gudrun Anderson Witrak Mark Hollabaugh Philip Yeagle COMMUNICATIONS GIFT COMMITTEE PROGRAM COMMITTEE COMMITTEE Jane Ranzenberger Goldstein Susan Myhre Hayes Natalie Larsen Gehringer Kris Yung Walseth Gudrun Anderson Witrak Mark Hollabaugh Philip Yeagle Mary Ellen Andersen Bonnie Ohrlund Ericson Sylvia Flo Anshus Barbara Anshus Battenberg Bob Freed Paul Burnett Beth Minear Cavert Michael Garland Robert Chamberlin Kathryn Hosmer Doutt Bob Gehringer Diane Lindgren Forsythe Ann Williams Garwick William Grimbol Dale Gasch John Hager Janice Burnham Haemig Christina Glasoe Mike Holmquist -

Event Booklet

2017 Undergraduate Research Symposium SDEPSCoR RESEARCH. EDUCATION. ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT. In partnership with Ramkota Hotel - Pierre, SD August 2-3, 2017 South Dakota Undergraduate Research Symposium Ramkota RiverCentre Conference Center Pierre, SD August 2-3, 2017 *All times are listed as Central Daylight Time Wednesday, August 2 Faculty Workshop 1:00-4:30 pm Next Generation Sequencing Workshop (Gallery D) Student Sessions 1:00-2:30 pm First Breakout Session • Ins and Outs of Medical/Health Professional Schools (Gallery E) Moderator: Dr. Mark Larson, Augustana University Panel: Dr. Paul Egland, Augustana Chief Health Professions Advisor; Dr. Charles Lamb, BHSU Chief Health Professions Advisor • Applying for Graduate School (Gallery B, C) Moderator: Dr. Brian Logue (SDSU) Panel: Dr. Mike West (SDSMT), Dr. Grant Crawford (SDSMT), Dr. Jon Kellar (SDSMT), Dr. Stan May (USD) 2:30-3:00 pm Break 3:00-4:30 pm Second Breakout Session • STEM Career Opportunities in South Dakota (Gallery B,C) Moderator: Dr. Melvin Ustad (SD GOED) Panel: Mark Anderson, SD Department of Labor; Kenna Hagan, Black Hills Energy; Pam Hilber, Avera Health; Heather Perry, Director of Policy and Special Projects, SD Bureau of Human Resources; Penny Sattgast, President, PCS Biotech Services; Matt Smart, Smart Software Solutions 4:00-5:30 pm Faculty Scientifc Sessions - BRIN Faculty (Lake Francis Case) 4:30-5:30 pm Site Visit Grad Poster Set Up (Discovery Center) 5:30—7:00 pm Dinner Keynote Presentation - Dr. Giselle Muller-Parker (NSF) (Gallery A,F,G) 7:00-8:00 pm Site Visit -

Initial Eligibility Contacts for Institutions Participating in the South Dakota Opportunity Scholarship Program

Initial Eligibility Contacts for Institutions Participating in the South Dakota Opportunity Scholarship Program Augustana University Black Hills State University Dakota State University Dakota Wesleyan University Tresse Evenson Taylor Phillips Jill Corbin Kristy Ehlebracht Director of Financial Aid Admissions Representative Scholarship Coordinator Associate Director of FA Augustana University Black Hills State University Dakota State University Dakota Wesleyan University 2001 S Summit Avenue 1200 University St. Unit 9502 820 N Washington Ave 1200 W. University Ave. Sioux Falls, SD 57197 Spearfish, SD 57799-9502 Madison, SD 57042 Mitchell, SD 57301 605-274-5216 605-642-6343 605-256-5307 605-995-2659 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Lake Area Technical College Mount Marty University Mitchell Technical College National American University Eric Schultz Kenneth Kocer Clayton Deuter Cheryl Bullinger Director of Enrollment Director of Financial Assistance Director of Admissions Director of Financial Aid Lake Area Technical Institute Mount Marty College Mitchell Technical Institute National American University 1201 Arrow Ave. 1105 West 8th Street 1800 East Spruce Street 321 Kansas City Street Watertown, SD 57201 Yankton, SD 57078 Mitchell, SD 57301 Rapid City, SD 57701 (605) 882-5284 Ext. 228 605-668-1589 1-800-684-1969 605-721-5213 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Northern State University Presentation College SD School of Mines & Technology South Dakota State University Becky Pribyl Amber Brockel Genene Sigler Melody Hall Director of Financial Aid Director of Financial Aid Admissions Senior Secretary Enrollment Services Center Northern State University Presentation College SD School of Mines and Tech. -

Study Group Powerpoint 2016 Provided by Creative Services AGENDA

Do not fear change | Change Fear Study Group PowerPoint 2016 Provided by Creative Services AGENDA Why #youarewelcomehere #youarewelcomehere Year 1 Impact and Statistics #youarewelcomehere Year 2 Questions /// Discussion Why #youarewelcomehere #youarewelcomehere Year 1 Impact and Statistics #youarewelcomehere Year 2 Questions /// Discussion Why Multiple factors drove creation of #youarewelcomehere Nationalism Safety Concerns (not Patriotism) (Rural vs. Urban) Immigration Campaign (ongoing debate) Fatigue Media Ignorance Fatigue (uninformed electors) 4 Starting a Movement Creation of #youarewelcomehere #I’llRideWithYou James Madison University Other Study Group Partners University of Vermont Roosevelt University Merrimack College Long Island University City College of New York 5 6 #youarewelcomehere Year 1 Why #youarewelcomehere Impact and Statistics #youarewelcomehere Year 2 Questions /// Discussion Growing #youarewelcomehere Temple University and NAFSA Jessica Sandberg, of Temple University, and NAFSA, lead the charge amongst other universities to promote use of #youarewelcomehere in photos, videos, and all social media platforms. 8 Explosion of Attention Universities /// Organizations /// Beyond Higher Education Alfred State College Alfred University American University American Harbor College 200+ Arizona State University Arkansas Tech University Augustana University Bard College Universities Bard College, The Levy Economics Institute Baruch College Bellevue College Bemidji State University Bexhill College Binghamton University Black -

Part-Time Faculty Employee Handbook

PART-TIME FACULTY EMPLOYEE HANDBOOK 2018-2019 Contents HISTORY OF AUGUSTANA UNIVERSITY ......................................................................................... 3 NOTICE TO ALL EMPLOYEES ............................................................................................................. 6 THE AUGUSTANA UNIVERSITY APPROACH .................................................................................. 7 AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT (ADA) POLICY ............................................................... 7 WORKPLACE VIOLENCE PREVENTION ........................................................................................ 31 ID CARDS ................................................................................................................................................. 32 PARKING .................................................................................................................................................. 32 SALE, SOLICITATION AND DISTRIBUTION .................................................................................. 36 ETHICAL STANDARDS ......................................................................................................................... 36 CAMPUS CONDUCT HOTLINE ........................................................................................................... 37 TITLE IX / HARRASMENT ................................................................................................................... 38 BREASTFEEDING POLICY .................................................................................................................