Filling the Metaphysical Landscape Chikako Sassa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

City of Santa Clarita Transit Development Plan Report Appendix Table of Contents Appendix A: Survey Instruments ................................................. A - 1 COMMUNITY SURVEY INSTRUMENT ............................................................................. A-1 ONBOARD SURVEY INSTRUMENT ................................................................................. A-2 COMMUTER SURVEY INSTRUMENT............................................................................... A-3 DIAL-A-RIDE SURVEYINSTRUMENT ................................................................................ A-4 SUPPLEMENTAL SCHOOL DAY SURVEY INSTRUMENT .................................................... A-6 Appendix B: Survey Frequencies .................................................. B - 1 COMMUNITY SURVEY FREQUENCIES ............................................................................. B-1 ONBOARD SURVEY FREQUENCIES ................................................................................. B-35 COMMUTER SURVEY FREQUENCIES .............................................................................. B-69 DIAL-A-RIDE SURVEY FREQUENCIES .............................................................................. B-88 SUPPLEMENTAL SCHOOL DAY SURVEY FREQUENCIES .................................................... B-102 Moore & Associates, Inc. | 2019 City of Santa Clarita Transit Development Plan Report Appendix A. Survey Instruments Exhibit A.1 Community Survey Instrument A - 1 Moore & Associates, Inc. | 2019 City of Santa -

Metrolink Upgrades to Include More Double-Tracking in Saugus | 08-23-2019

10/1/2019 SCVNews.com | Metrolink Upgrades to Include More Double-Tracking in Saugus | 08-23-2019 SEARCH SUBSCRIBE ADVERTISE TV NEWS HISTORY SOCIAL CONTACT ABOUT [Sign Up Now] to Receive Our FREE Daily SCVTV-SCVNews Digest by E-Mail Search Inside Metrolink Upgrades to Include More Double-Tracking in Saugus SCV News Stephen K. Peeples | Friday, Aug 23, 2019 SCV Sports SCV Business SCV Education Arts & Culture Op-Ed / Blogs Things To Do Extras Earthquakes Weather Santa Clarita CA Mostly sunny 44°F Calendar Extending double-tracking and upgrading the Santa Clarita train station platform in Saugus are among the proposed infrastructure improvements to the Metrolink Antelope Valley Line approved by the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority on Cl July 25. Ge Th Today in The improvements include adding 1.6 miles of new track to double-track the stretch from the end of the Bouquet Junction bend N S.C.V. History northeast to Golden Oak Road, and widening Santa Clarita Station’s platform to accommodate the new two-track line. October 1 Once through the environmental impact gauntlet and the final design and funding are in place, the proposed projects would cost an 2017 - One SCV resident, John estimated $173.5 million and require two and a half years to 10 years complete, according to Metro officials. Phippen, killed and at least 9 The improvements would speed up Metrolink rail service and continue building passenger ridership on the 76.6-mile Antelope Valley others wounded Line, or AVL, which connects Lancaster in North Los Angeles County with Union Station in Downtown Los Angeles. -

COMMUTER RAIL in SUBURBAN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA a Thesis

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE THE GROWTH EFFECT: COMMUTER RAIL IN SUBURBAN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Geography By Matthew E. Nordstrom August 2015 Signature Page The thesis of Matthew Nordstrom approved: ________________________________________ _______________ Dr. James Craine Date ________________________________________ _______________ Dr. Mintesnot Woldeamanuel Date ________________________________________ _______________ Dr. Ronald Davidson, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my committee chair, Dr. Ron Davidson who has been a mentor for me since my undergraduate days. I would also like to thank my other committee members, Dr. James Craine and Mintesnot Woldeamanuel for their support. I also want to thank my wife who has given me tremendous support and has helped push me through so I can do what I need to do to chase my dreams. Lastly, I also want to thank my mother, a schoolteacher who is passionate about education and has stuck by my side throughout my schooling years, always giving me support and bringing out the best in me. iii Table of Contents Signature Page ................................................................................................................................ ii Acknowledgments.......................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables ................................................................................................................................ -

City of Santa Clarita General Plan Circulation

City of Santa Clarita General Plan Circulation CIRCULATION ELEMENT June, 2011 PART 1: BACKGROUND AND CIRCULATION ISSUES A. Purpose and Intent of the Circulation Element The Santa Clarita Valley’s circulation system provides vital connections linking neighborhoods, services, and employment centers throughout the community and the region. A comprehensive transportation network of roadways, multi-use trails and bike paths, bus transit, and commuter rail provides mobility options to Valley residents and businesses. Planning for the ultimate location and capacity of circulation improvements will also enhance economic strength and quality of life in the Valley. The Circulation Element plans for the continued development of efficient, cost-effective and comprehensive transportation systems that are consistent with regional plans, local needs, and the Valley’s community character. The Circulation Element complements and supports the Land Use Element, insofar as a cohesive land use pattern cannot be achieved without adequate circulation. The Circulation Element identifies and promotes a variety of techniques for improving mobility that go beyond planning for construction of new streets and highways. These techniques include: development of alternative travel modes and support facilities; increased efficiency and capacity of existing systems through management strategies; and coordination of land use planning with transportation planning by promoting concentrated, mixed-use development near transit facilities. B. Background The California Government Code describes conditions and data that must be researched, analyzed, and discussed in a Circulation Element. Section 65302(b) states that the general plan shall include the general location and extent of existing and proposed major thoroughfares, transportation routes, terminals and other local public utilities and facilities. -

NOP) Is to Notify All Interested Agencies, Organizations, and Individuals That Metro Has Extended the Public Scoping Period and Scheduled a New Scoping Meeting

UPDATED NOTICE OF PREPARATION OF A DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT DATE: October 20, 2020 TO: Agencies, Organizations, and Interested Parties SUBJECT: Updated Notice of Preparation of a Draft Environmental Impact Report PROJECT TITLE: Antelope Valley Line Capacity and Service Improvements Program FROM: Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority PROJECT LOCATION AND ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING: The Antelope Valley Line (AVL) is a 76.6-mile-long commuter rail line that serves Northern Los Angeles County as part of the Metrolink system. The AVL extends from Los Angeles Union Station in the City of Los Angeles and terminates in the City of Lancaster with stations in the cities and communities of Los Angeles, Glendale, Burbank, Sun Valley, Sylmar, San Fernando, Newhall, Santa Clarita, Acton, Palmdale, and Lancaster. The Antelope Valley Line Capacity and Service Improvements Program (Proposed Project) proposes expansion of commuter rail service along the entire AVL corridor as well as three capital improvements required to facilitate the proposed service increase. The three capital improvements would be located along the AVL corridor, one of which is within the City of Santa Clarita, one in City of Los Angeles, and the third would be located in the City of Lancaster at the Lancaster Terminal (see Figure 1). These capital improvement projects together with the Brighton Street to McGinley Avenue double-track project, which has been environmentally cleared separately as part of the Brighton to Roxford Double Track Project, will enable increased commuter rail services on the railroad corridor. PROJECT INITIATION: The Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro), the Lead Agency, initiated a Draft Environmental Impact Report (EIR) and Public Scoping period on October 1, 2020 for the Proposed Project pursuant to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). -

11.0 References

11.0 REFERENCES AirNav.com L70 Agua Dulce Airport, Agua Dulce, California, http://www.airnav.com/airport/L70, Accessed on September 4, 2009. Barry, T.M. and J.A. Reagan. 1978. FHWA Highway Traffic Noise Prediction Model (FHWA-RD-77-108). California Air Resources Board. 2001. Ozone Transport: 2001 Review. California Air Resources Board. 2007. “Air Quality Maps: Estimated Cancer Risk from Air Toxics - 2001 Estimated Inhalation Cancer Risk Per Million People.” www.arb.ca.gov/toxics/cti/hlthrisk /hlthrisk.htm. California Air Resources Board. 2003. “Area Designations.” http://www.arb.ca.gov/desig/adm/Define .htm. California Air Resources Board. “California 1990 Greenhouse Gas Emissions Level and 2020 Limit.” http://www.arb.ca.gov/cc/inventory/1990level/1990level.htm. California Air Resource Board, “Low Carbon Fuel Standard Program,” http://www.arb.ca.gov/fuels/lcfs /lcfs.htm. California Building Standards Commission. 2007. California Fire Code. California Code of Regulations, Title 24, Part 9. California Climate Action Registry. 2008. General Reporting Protocol: Reporting Entity-Wide Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Version 3.0. Los Angeles: California Climate Action Registry. California Climate Action Registry. n.d. “Reporting Online Tool, Public Annual Entity Emissions.” http://www.climateregistry.org/CARROT/public/Reports.aspx. California Community Care Licensing Division. 2008. “Search for a Licensed Facility.” http://www.ccld .ca.gov/docs/ccld_search/ccld_search.aspx. California Department of Conservation Division of Land Resource Protection. 2006. Farmland Mapping and Monitoring Program. California Farmland Conversion Report 2002–2004. California Department of Conservation Division of Land Resource Protection. 2004. Farmland Mapping and Monitoring Program. California Farmland Conversion Report 2000–2002. -

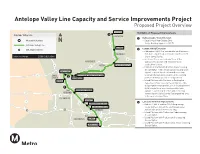

Antelope Valley Line Capacity and Service Improvements Project Proposed Project Overview

Antelope Valley Line Capacity and Service Improvements Project Proposed Project Overview LANCASTER Highlights of Proposed Improvements 3 Antelope Valley Line LANCASTER 1 Balboa Double-Track Extension Metrolink Stations > Double track from Balboa Bl to 14 Sierra Highway (approx. 6,300 ft). Antelope Valley Line PALMDALE Canyon Sliding Extension # AVL Improvements 2 > Add approx. 8,400 ft of new double track between PALMDALE Soledad Canyon Road and Golden Oak Road in the Subject to Change 22-0024 ©2021 LACMTA City of Santa Clarita. 138 > Inclusion of a second side-platform at the AGUA DULCE Santa Clarita Station and crossover track 18 138 south of the station. 5 ACTON VINCENT GRADE/ACTON 14 > Platform to Platform Pedestrian Undercrossing Design Option – This design option would provide SANTA CLARITA a grade separated pedestrian undercrossingPHELAN 126 at Santa Clarita Station to connect the existing SANTA 2 VISTA CANYON (UNDER CONSTRUCTION) CLARITA VIA PRINCESSA platform to the proposed second platform. 138 NEWHALL > Island Platform with Platform to Parking Lot Pedestrian Undercrossing Design Option - This design option would provide a new island platform 1 (with two platform faces) and would include SAN SYLMAR/SAN FERNANDO a grade-separated pedestrian undercrossing FERNANDO connecting the Santa Clarita Station parking area 118 210 to the new island platform. LOS ANGELES SUN VALLEY 23 Lancaster Terminal Improvements 170 3 BURBANK AIRPORT-NORTH > Add one 1,000-ft and two 500-ft long storage 27 BURBANK-DOWNTOWN tracks in the vicinity of the existing Lancaster 101 101 GLENDALE Station with provisions for refueling. 134 > Island Platform with Pedestrian Undercrossing 210 Design Option. -

100621 LA County Initial Study Checklist (00092018-2).DOC

Environmental Checklist Form (DRAFT Initial Study) County of Los Angeles, Department of Regional Planning Project title: Canyon View Estates/Project No. 2016-002179; Tract Map No. 74650; Conditional Use Permit No. 2016004409; Oak Tree Permit No. RPPL2017009209; and Environmental Assessment No. 20160044100 Lead agency name and address: Los Angeles County, 320 West Temple Street, Los Angeles, CA 90012 Contact Person and phone number: Marie Pavlovic (213) 974-6433 Project sponsor’s name and address: Jemstreet Properties, 1435 Reynolds Court, Thousand Oaks, CA 91362 Project location: Regionally, the Project site is situated west of Interstate 5 (I-5), north of California State Route 188 (SR-118), south of California State Route 126 (SR-126), and east of the Los Angeles-Ventura County boundary; refer to Figure 1, Regional Map. Locally, the Project site is located approximately 1,000 feet south of the intersection of Pico Canyon Road and Stevenson Ranch Parkway, immediately east of the Southern Oaks residential community (Southern Oaks community) and west of the Sunset Point residential community (Sunset Point community); refer to Figure 2, Aerial Photograph. APN: 2826-020-012, 2826-020-013 and 2826-020-061 USGS Quad: Newhall and Oat Mountain Gross Acreage: 94.38 gross acres General plan designation: N/A Community/Area wide Plan designation: RL2 – Rural Land (1 du per 2 acres) Zoning: A-2-2 Heavy Agriculture (2-acre minimum lot size); no Community Standards District Description of project: The Canyon View Estates Project (Project) proposes to develop 37 single-family residential lots, two open space lots, one public water quality basin, and five public facility lots (basins); refer to Figure 3, Tentative Tract Map. -

Existing Conditions Report

Antelope Valley Line Study Appendix I Existing Conditions Report AVL ANTELOPE VALLEY LINE STUDY Contract No. PS-2415-3024-03 APPENDIX 1 Existing Conditions Report Prepared for: Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority Prepared by: Review Copy Date Initials Originator 7/27/18 SM 444 South Flower Street Checker 8/3/18 LF Suite 800 Back Checker 8/7/18 SM Los Angeles, California 90071 Format Checker 8/8/18 SM Approved by 8/8/18 LF August 8, 2018 Contents CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION AND STUDY PURPOSE ......................................................................... 1-1 1.1 OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.2 CORRIDOR CONTEXT ........................................................................................... 1-14 1.3 Section 1 Rerefences ............................................................................................... 1-18 2 ANTELOPE VALLEY PHYSICAL AND OPERATIONAL CHARACTERISTICS ..................... 2-1 2.1 EXISTING INFRASTRUCTURE CONFIGURATION AND ASSESTS ....................... 2-1 2.2 OPERATIONS ........................................................................................................... 2-7 2.3 ROLLING STOCK ................................................................................................... 2-19 2.4 CAPITAL IMPROVEMENTS ................................................................................... 2-21 2.5 REHABILITATION NEEDS .................................................................................... -

Call to Order City of Santa Clarita City Council

CITY OF SANTA CLARITA CITY COUNCIL MINUTES OF SPECIAL MEETING 6:00 P.M. MINUTES OF REGULAR MEETING 7:00 P.M. DECEMBER 10, 2002 CALL TO ORDER Mayor Ferry called to order the special meeting of the City Council at 6: 10 p.m. ROLL CALL All Councilmembers were present. NATIONAL ANTHEM Corey Ruffner sang the National Anthem. FLAG SALUTE Major Colin Smyth led the flag salute. PUBLIC PARTICIPATION Addressing the Council was Allan Cameron regarding the outgoing Mayor. REMARKS BY OUTGOING MAYOR Mayor Ferry commented on his year as Mayor and introduced his sons Nick and Jake. OUTGOING MAYOR MAKES PRESENTATION TO COUNCILMEMBERS AND STAFF Mayor Ferry presented City badges to department directors, the City Manager and Councilmembers. PRESENTATION TO OUTGOING MAYOR Addressing the Council and making comments to the outgoing Mayor was Mayor Pro-Tern Cameron Smyth; Linda Lambourne representing Congressman Buck McKean; Fred Trueblood representing State Assemblyman Keith Richman; Millie Jones representing Los Angeles County Supervisor Mike Antonovich; Patti Kelly representing State Senators Pete Knight and Tom McClintock; Rick Winsman representing SCV Chamber of Commerce; Penny Upton representing SafeRides; Bruce Fortine representing College of the Canyons; Pat Hanrion representing William S. Hart Union School District; Dr. Paul Priesz representing Valencia High School ASB; Teresa Todd representing Sulphur Springs Union Elementary School District; Rose Diaz representing Saugus Union Elementary School District; Judy Umeck representing SCV Trustees Association; -

Notice of Preparation of a Draft Environmental Impact Report

NOTICE OF PREPARATION OF A DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT DATE: October 1, 2020 TO: Agencies, Organizations, and Interested Parties SUBJECT: Notice of Preparation of a Draft Environmental Impact Report PROJECT TITLE: Antelope Valley Line Capacity and Service Improvements Program FROM: Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority PROJECT LOCATION AND ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING: The Antelope Valley Line (AVL) is a 76.6-mile-long commuter rail line that serves Northern Los Angeles County as part of the Metrolink system. The AVL extends from Los Angeles Union Station in the City of Los Angeles and terminates in the City of Lancaster with stations in the cities and communities of Los Angeles, Glendale, Burbank, Sun Valley, Sylmar, San Fernando, Newhall, Santa Clarita, Acton, Palmdale, and Lancaster. The Antelope Valley Line Capacity and Service Improvements Program (Proposed Project) proposes expansion of commuter rail service along the entire AVL corridor as well as three capital improvements required to facilitate the proposed service increase. The three capital improvements would be located along the AVL corridor, one of which is within the City of Santa Clarita, one in City of Los Angeles, and the third would be located in the City of Lancaster at the Lancaster Terminal (see Figure 1). These capital improvement projects together with the Brighton Street to McGinley Avenue double-track project, which has been environmentally cleared separately as part of the Brighton to Roxford Double Track Project, will enable increased commuter rail services on the railroad corridor. PROJECT INITIATION: The Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro), the Lead Agency, has initiated a Draft Environmental Impact Report (EIR) for the Proposed Project pursuant to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). -

Antelope Valley Line Study

Antelope Valley Line Study Final Report AVL ANTELOPE VALLEY LINE STUDY Contract No. PS-2415-3024-03 Final Report Prepared for: Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority Prepared by: 444 South Flower Street Suite 800 Review Copy Los Angeles, California 90071 Originator FNichols 9/30/19 In association with: Checker RMarcus 10/9/19 Pacific Railway Enterprises, Inc. Back Checker TLichterman 10/10/19 Rail Surveyors and Engineers, Inc. Format Checker CDavis 10/17/19 Approved by FNichols 10/18/19 October 22, 2019 Contents CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 1 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Study Purpose .............................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Objectives, Assumptions and Study Scope ................................................................ 2 1.3 Study Participants and Stakeholder/Public Engagement ........................................... 3 2 EXISTING CONDITIONS ........................................................................................................ 4 2.1 Regional Growth and Economic Development .......................................................... 4 2.2 Rail Service ................................................................................................................... 4 2.3 Rail Infrastructure, Stations,