01 089085 Schimmelfennig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Circles and Hemispheres of Integration

Circles and Hemispheres of Integration The Development of a System of Graded European Union Membership Frank Schimmelfennig, ETH Zürich, September 2014 Abstract The study of integration has focused on organizational growth and on the “deepening” and “widening” of regional organizations. By contrast, this paper analyzes organizational differentiation. It conceives of differentiation as a process, in which states either refuse to be integrated or are being refused integration by the core member states but all parties find value in creating in-between grades of membership. A particularly fine-grained system of graded membership has developed in Europe. This paper describes its development and seeks to explain the positioning and movement of states in this system. I argue that the “refusers” and the “refused” are located in different “hemispheres” of integration that cut across the “circles” of membership, and in which membership status is driven by opposite or different factors. The states of the “hemisphere of bad governance” are refused further integration because the core members are concerned about efficiency losses, redistribution, and a dilution of the EU’s democratic identity. By contrast, the states of the “hemisphere of affordable nationalism” refuse further integration because they care strongly about national identity and sovereignty and are wealthy and well-governed enough to resist. A panel analysis of European countries since the early 1990s shows that membership status among the refused countries increases with wealth, democracy, -

2505 Academic Programme

Contents Welcome Welcome messages ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… p.2 Organizing committees ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… p.4 ECPR Standing Group on the EU .. …………………………………………………………………………………………………. p.5 The University of Trento ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. p.5 Academic program Schedule of activities …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… p.6 Jo urnal of Common Market Studies Keynote Lecture ………………………………………………………………….. p.7 Plenary Roundtable ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… p.7 Other events ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… p.8 List of Sections …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. p.9 List of Panels by Section ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. p.10 List of Panels by Session time ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. p.47 Practical information Location ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. p.48 Regist ration ……………………………………………… …………………………………………………………………………………. p.48 Floor plans …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… p.49 Technology …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… p.51 Where to eat ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… p.51 Further information ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… p.5 2 List of registered participants ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… p.53 1 Welcome Welcome messages Dear Participants, it is my pleasure to welcome you to the University of Trento on the occasion of the 8th Pan-European Conference on the EU organized by the ECPR Standing Group on the European -

With 126 Panels, Nearly 500 Researc

Welcome to the 14th Biennial Conference of the European Union Studies Association in Boston! With 126 panels, nearly 500 researchers and practitioners from over 250 institutions across the world are participating in panels, plenaries and roundtables, making this one of the largest EUSA Conferences. We have a diversity of topics and disciplines represented in the program, along with key plenary sessions, followed by evening receptions open to all participants. Among the highlights of the program is an evening plenary panel on Friday: Neoliberal Policies and their Alternatives, followed by a keynote lecture by Thomas Piketty, Inequality in the Europe- and What the EU Could Do About it. Immediately thereafter, there is a reception hosted by the Journal of Common Market Studies. Two other plenaries will focus on the Future of EU Federalism, and the Future of Transatlantic Relations, the latter featuring Baroness Catherine Ashton (former High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy). A panel and discussion Honoring Lifetime Achievement in European Studies Award Recipient James Caporaso, former Chair of EUSA, will take place on Saturday during the lunch time session. A presentation of EUSA Prize Winners will be held on Thursday Evening, where we will award the Ernst Haas Fellowship, Lifetime Achievement Award, Best Book, Best Dissertation and Best Paper Prizes. This will be followed by a EUSA Reception. There are also a number of interest group business meetings listed in the program that conference participants are welcome to attend. The European Union Studies Association is grateful for a generous conference grant from the Lifelong Learning Programme of the European Commission, and logistical assistance, financial sponsorship and organizational support from the Journal of Common Market Studies, College of Europe, Fulbright Commission, Northeastern University, and the University of Pittsburgh, which supports EUSA on its campus. -

Why European Union Member States Opt out of Integration

The Choice for Differentiated Europe: Why European Union Member States Opt out of Integration Thomas Winzen and Frank Schimmelfennig Center for Comparative and International Studies, ETH Zurich, Switzerland1 Paper prepared for the 14th biennial conference of the European Union Studies Association, 5-7 March 2015, Boston, MA. Abstract Since the early 1990s, European integration has become differentiated integration. Treaty revisions and enlargements have resulted in opt-outs for countries such as Britain or Denmark, and in policy areas such as monetary union. Analysing under what conditions member states make use of the opportunity to opt- out or exclude other countries from European integration, we argue that different explanations apply to treaty and accession negotiations respectively. Threatening to block deeper integration, member states with strong national identities secure differentiations in treaty reform, particularly regarding the integration of core state powers. In enlargement, in turn, old member states fear economic disadvantages and low administrative capacity and, therefore impose differentiation on poor newcomers. A logistic regression analysis of the use of differentiation opportunities by member and candidate countries from Maastricht in 1993 to the Croatian accession in 2013 lends empirical support to these arguments. Introduction2 Since the early 1990s, European integration has become differentiated integration. This period has been characterized by a far-reaching extension of the European Union’s policy scope beyond -

Central and Eastern Europe in the European Union

This work has been published by the European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. © European University Institute 2018 Editorial matter and selection © Michał Matlak, Frank Schimmelfennig, Tomasz P. Woźniakowski, 2018 Chapters © authors individually 2018 doi:10.2870/675963 ISBN:978-92-9084-707-6 QM-06-18-198-EN-N This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Artwork: ©Shutterstock: patrice6000 The European Commission supports the EUI through the European Union budget. This publication reflects the views only of the author(s), and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. EUROPEANIZATION REVISITED: CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE IN THE EUROPEAN UNION Editors: Michał Matlak, Frank Schimmelfennig and Tomasz P. Woźniakowski In memoriam Nicky Owtram TABLE OF CONTENTS Biographies 1 Acknowledgments 4 Foreword 5 Europeanization Revisited: An Introduction Tomasz P. Woźniakowski, Frank Schimmelfennig and Michał Matlak 6 The Europeanization of Eastern Europe: the External Incentives Model Revisited Frank Schimmelfennig and Ulrich Sedelmeier 19 New -

European Integration (Theory) in Times of Crisis a Comparison of the Euro and Schengen Crises

European Integration (Theory) in Times of Crisis A comparison of the Euro and Schengen crises Frank Schimmelfennig, ETH Zürich, [email protected] Abstract The European Union has gone through major crises of its two flagship projects of the 1990s: the Euro and Schengen. Both crises had structurally similar causes and beginnings: exogenous shocks exposed the functional shortcomings of both integration projects and produced sharp distributional conflict among governments as well as an unprecedented politicization of European integration in member state societies. Yet they have resulted in significantly different outcomes: whereas the Euro crisis has brought about a major deepening of integration, the Schengen crisis has not. I put forward a neofunctionalist explanation of these different outcomes, which emphasizes variation in transnational interdependence and supranational capacity across the two policy areas. Acknowledgments For comments on previous versions of the paper, I thank audiences at an ACCESS EUROPE seminar at VU Amsterdam, the 2017 annual conference of the Swiss Political Science Association in St. Gallen, the 2017 EUSA Convention in Miami, and the Euro-CEFG workshop at the University of Rotterdam. Special thanks to Klaus Armingeon, Ben Crum, Madeleine Hosli, Matthias Mattijs, Thomas Spijkerboer, and Jonathan Zeitlin. Introduction The European Union (EU) has come to operate in crisis mode permanently. When the Treaty of Lisbon entered into force in December 2009, the EU finally appeared to have achieved institutional consolidation after the failure of the Constitutional Treaty. Around the same time, however, the mounting Greek balance-of-payment problem signaled the start of the Euro crisis. As soon as “Grexit” was averted in dramatic negotiations in July 2015, the migration flow across the Aegean Sea spiraled out of control, triggering a crisis of the Schengen regime of free movement across internal EU borders. -

Differentiated Integration in the European Union

DIFFERENTlATED INTEGRATION IN THE EUROPEAN UNION: MANY CONCEPTS, SPARSE THEORY, FEW DATA Katharina Holzinger and Frank Schimmelfennig ABSTRACT Differentiated integration has been the subjecc of political discussion and academic thought for a long time. Ir has also become an important feature of European integration since the 1990s. By contrast, it is astonishing how poor our research and knowledge about the phenomenon iso Whereas there is an abundance of conceptual work and some normative analysis, positive theories on the causes or effects of differentiated integration are rare. Empirical analysis has concentrated on a few important cases of treaty law (such as EMU and Schengen) while there is no systematic knowledge about differentiated integration in secondary law. The aim of this article is therefore twofold: to review the existing typological and theory-oriented research and to outline a research agenda striving for systematic empirical and explanatory knowledge. KEY WORDS Differentiated integration; European integration; flexible integration. 1. INTRODUCTION Some rules and policies of the European Union (such as monetary policy) apply to a subset of the member states only; others (such as many internal market rules) have been adopted by non-members; others again (such as the Schengen regime) do not apply in some of the member states but apply in some non member states. All of these policies, in which the territorial extension of Euro-· pean Union (EU) membership and EU rule validity are incongruent, are cases of differentiated (or flexible) integration. Differentiated integration has been the subject of political discussion and aca demic thought for a long time. Since the 1970s, a great number of concepts and proposals have been put forward by political practitioners as weH as legal and political science scholars. -

NATO's Enlargement to the East: an Analysis of Collective Decision-Making EAPC-NATO Individual Fellowship Report 1998-2000

NATO's Enlargement to the East: An Analysis of Collective Decision-making EAPC-NATO Individual Fellowship Report 1998-2000 Frank Schimmelfennig Dr. Frank Schimmelfennig Institut für Politikwissenschaft Technische Universität Darmstadt Residenzschloss D-64283 Darmstadt Germany Tel.: (49) (7121) 670487 Fax: (49) (7121) 907138 E-Mail: [email protected] URL: http://www.ifs.tu-darmstadt.de/pg/regorgs/regorgh.htm 2 Acknowledgments I gratefully acknowledge funding for the research presented here by an EAPC-NATO Fellowship for the period 1998-2000. I am highly indebted to my interview partners (see list in the appendix) for sharing their precious time and their insights with me. I further thank Karen Donfried, Chris Donnelly, Gunther Hellmann, Johanna Möhring, and Frank Umbach for helping me to get in contact with the interviewees and Thomas Risse and Klaus Dieter Wolf for supporting my application for the fellowship. 1 1 Introduction At NATO's Madrid summit of July 1997, at which the alliance decided to invite the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland to become members, Czech deputy minister of foreign affairs Vondra approached a group of U.S. senators participating at the summit on behalf of the Senate NATO Observer Group and asked them, "Why did you choose us?" The answer he got was, "We like you, we think you like us, and then you talked it into our heads for so long that we could not do otherwise." (Interview Member of CEEC Delegation to NATO) This little anecdote could serve as an epigraph for the analysis of the collective decision- making process on NATO's Eastern enlargement which is the subject of this report. -

October 1995 to Present

Curriculum Vitae Sandra Lavenex Born on 28.1.1970 in Milano (Italy) Swiss national Two children (born 2004 and 2007) Employment Since 8/2014 Full Professor of European and International Politics, University of Geneva Since 2007 Visiting Professor, College of Europe, Natolin Campus 2006 - 2014 Associate, then full Professor for International Relations and Global Governance at the University of Lucerne, Founding Member of the Department of Political Science and Director of Studies, Interdisciplinary Master of Arts in World Politics and World Society 2001-2006 Assistant Professor for European and International Studies at the University of Bern, Institute of Political Science (‘Assistenzprofessorin’) 1999-2001 ‘Oberassistentin’ at the University of Zurich, Center for International Studies (CIS) 1995-1998 Researcher, European University Institute, Florence 1991-1994 Research and teaching assistant at the University of Konstanz, Faculty of Public Administration (Proff. H. Elsenhans, W. Seibel and T. Risse) Education 2009 Habilitation, University of Bern, Thesis title: EU neighbourhood relations as external governance 1995-1999 PhD, European University Institute, Florence, Social and Political Science Department; Thesis title: The Europeanisation of Refugee Policies. Between Human Rights and Internal Security, Jury: Proff. A. Héritier, T. Risse, K. Eder and D. Bigo (not graded) 1989-1995 University of Konstanz, Germany: Diplom-Verwaltungswissenschaften (grade 1) 1981-1989 Kopernikus-Gymnasium, Ratingen, Germany: Abitur (grade 1.2) 1976-1981 Scuola -

Institut Für Höhere Studien (IHS), Wien

www.ssoar.info The constitutionalization of the European Union: explaining the parliamentarization and institutionalization of human rights Rittberger, Berthold; Schimmelfennig, Frank Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Forschungsbericht / research report Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Rittberger, B., & Schimmelfennig, F. (2005). The constitutionalization of the European Union: explaining the parliamentarization and institutionalization of human rights. (Reihe Politikwissenschaft / Institut für Höhere Studien, Abt. Politikwissenschaft, 104). Wien: Institut für Höhere Studien (IHS), Wien. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168- ssoar-245857 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use. -

Thursday Friday Saturday

SPECIAL EVENTS Thursday Lunch Plenary I 12:00 p.m. – 1:30 p.m. Grand Ballroom I Roundtable: EU Dis-Integration Literature and its Skeptics Chair: Rachel Epstein (University of Denver) Participants Martin Rhodes (University of Denver) Tanja Börzel (Freie Universität Berlin) Andrew Moravcsik (Princeton University) R. Daniel Kelemen (Rutgers University) Milada Vachudova (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill) JCMS Lecture 5:15 p.m. – 6:45 p.m. Grand Ballroom I Speaker: Ben Rosamond (University of Copenhagen) Welcoming Reception 6:45 p.m. – 7:45 p.m. South Convention Lobby Sponsored by JCMS, The Colorado European Union Center of Excellence and EUSA Friday Lunch Plenary II 12:00 p.m. – 1:30 p.m. Grand Ballroom I Roundtable - The Euro at 20: Lessons Learned and Possible Futures Chair: Matthias Matthijs (Johns Hopkins University) Participants Mark Blyth (Brown University) Alison Johnston (Oregon State University) Erik Jones (Johns Hopkins University) Waltraud Schelkle (London School of Economics) Kate McNamara (Georgetown University) EUSA Awards Presentations 5:15 p.m. – 5:45 p.m. Grand Ballroom I EUSA Award for Lifetime Achievement in European Studies Vivien Schmidt EUSA Reception 5:45 p.m. – 7:15 p.m. South Convention Lobby Saturday Lunch Plenary III 12:00 p.m. -1:30 p.m. Grand Ballroom I Panel Honoring Vivien Schmidt – EUSA Lifetime Achievement Award Recipient Chair: Abe Newman (Georgetown University) Participants Tanja Börzel (Freie Universität Berlin) Matthias Matthijs (Johns Hopkins University) Kalypso Nicolaïdis (University of Oxford) George Ross (Université de Montreal) Recipient 2017 EUSA Lifetime Achievement Award Alberta Sbragia (University of Pittsburgh) Recipient 2013 EUSA Lifetime Achievement Award College of Europe – Fulbright Reception 3:15 p.m. -

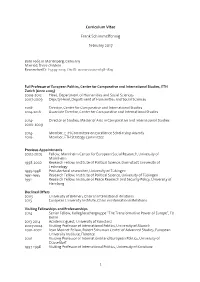

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Frank Schimmelfennig February 2017 Born 1963 in Marienberg, Germany Married, three children ResearcherID: J-5339-2013; OrcID: 0000-0002-1638-1819 Full Professor of European Politics, Center for Comparative and International Studies, ETH Zurich (since 2005) 2009-2012 Head, Department of Humanities and Social Sciences 2007-2009 Deputy Head, Department of Humanities and Social Sciences 2016- Director, Center for Comparative and International Studies 2014-2016 Associate Director, Center for Comparative and International Studies 2014- Director of Studies, Master of Arts in Comparative and International Studies 2006-2009 2014- Member, ETH Committee on Excellence Scholarship Awards 2016- Member, ETH Strategy Committee Previous Appointments 2002-2005 Fellow, Mannheim Center for European Social Research, University of Mannheim 1998-2002 Research Fellow, Institute of Political Science, Darmstadt University of Technology 1995-1998 Post-doctoral researcher, University of Tübingen 1991-1995 Research Fellow, Institute of Political Science, University of Tübingen 1991 Research Fellow, Institute of Peace Research and Security Policy, University of Hamburg Declined Offers 2005 University of Bremen, Chair in International Relations 2013 European University Institute, Chair in International Relations Visiting Fellowships and Professorships 2014 Senior Fellow, Kollegforschergruppe “The Transformative Power of Europe”, FU Berlin 2013-2014 Academic guest, University of Konstanz 2003-2004 Visiting Professor of International Politics, University