Homeschool an American History Milton Gaither

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thursday, March 11, 2021 Home-Delivered $1.90, Retail $2.20

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI THURSDAY, MARCH 11, 2021 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.20 PAGE 3 ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT PAGES 23-26 POLICE GISBORNE ACCUSED OF GALLERY ‘RACIALLY CLOSING PROFILING’ ITS DOORS PAGE 10 KIDS INSIDE TODAY CRUISING BACK TO GISBORNE: Eastland Port has 23 cruise ship visits scheduled for next summer, depending on the reopening of New Zealand borders. The Oosterdam (pictured) was a regular visitor to Gisborne in the early years of cruise ship visits here and she will be back twice in early December and early February next summer if the borders reopen. STORY ON PAGE 3 File picture A WOMAN who blew the whistle on Enterprises Limited (BEL) by his Matawai farmer John Bracken’s alleged Gisborne accountant, who unwittingly $17.4 million tax scam has given evidence prepared them using bank transactions in his High Court trial at Gisborne. manipulated by Bracken and false GST Ex-lover a She claimed Bracken was her lover, invoices he submitted. that they lived together in Auckland Bracken’s pleas to the charges have when he was regularly there for been deemed not guilty because he his export business and that she refuses to enter any. He says the charges unknowingly helped him with his scam are not his to answer — that as a by surreptitiously producing false beneficiary of a Maori Incorporation, he is invoices. protected under Te Ture Whenua Maori Bracken did not dispute their Act 1993. woman involvement but in cross-examination of Bracken is representing himself but her conveyed a situation in which she has literacy problems, so is being assisted was a woman scorned who squealed to by his wife and a McKenzie Friend the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) because of (someone who attends court in support her unfulfilled romantic designs on him. -

Ex-Captain Dhoni out of India's List of Contracted Cricketers

44 Friday Sports Friday, January 17, 2020 Ex-captain Dhoni out of India’s list of contracted cricketers NEW DELHI: MS Dhoni was absent from the Virat Kohli in 2017. list of centrally contracted players published by However Dhoni may be eyeing a last hurrah the Indian cricket board yesterday, raising fresh at the Twenty20 World Cup in October and speculation about the 38-year-old warhorse’s November in Australia. future. He is expected to lead the Chennai Super Dhoni has not appeared for club or country Kings in the Indian Premier League (IPL) this since the World Cup in July and the wicket- April-May. keeper-batsman has been expected to an- The Indian selectors have been grooming nounce his retirement for some time. young stumper Rishabh Pant, 22, to fill Dhoni’s The former captain of the national side, who gloves. Previously Dhoni was in the A-grade serves as an honorary lieutenant colonel in the category of the Board of Control for Cricket in army reserves, spent part of last year with his India (BCCI) central list, earning a guaranteed unit in strife-torn Kashmir — missing an ODI $715,000. tour of the West Indies. Pant is among 11 players listed in the A- He has not featured in any series since and grade contract with batsman KL Rahul taking was not named as part of the squad to tour Dhoni’s place. Kohli, senior batsman Rohit New Zealand later this month. Sharma and paceman Jasprit Bumrah are guar- He quit Test cricket in 2014 but continued to anteed at least $1 million each in the A-plus be India’s batting mainstay in limited-overs category for the period October 2019 to Sep- MS Dhoni cricket despite passing on the captaincy to tember 2020. -

Cricket Museum

EDUCATION EXHIBITIONS Museum Volunteer Michael Childs (right) Teacher Resource taking an ‘Historical Cricket ‘The Greatest New Zealand Cricket X1’ The museum has recently produced a Teacher’s Resource Plaques’ Tour of the Basin Commenced 17 March 2004 Reserve, New Zealand NEW ZEALAND Workbook in partnership with the Wellington Museum’s Trust. Cricket Museum Open This exhibition of New Zealand cricket greats features a selected XI (see exhibition Compiled by Carolyn Patchett, Education Co-ordinator of the Day 14.03.04 montage on front cover of newsletter) chosen from a short-list of 60 players, by two Museum of Wellington City and Sea, the resource has been Photo: Mark Coote ex-national convenors of selectors Don Neely and Frank Cameron, and Gavin Larsen, CRICKET MUSEUM prepared for Level 3, 4, and 5 students and is designed to Wellington Museums Trust the ex-test and one-day cricketer. encourage teachers and students to explore the world of cricket Archives at the museum. The idea for the exhibition followed the model of the successful ’The Greatest All Black Team’ project run by the Sunday Star Times in July 2003, in which readers were invited The 18 page workbook is being supplied free to schools with to chose their greatest All Black XV and the intention of raising awareness of the New Zealand Cricket match that against a selection made by Museum as an education resource and to give teachers and an expert panel. The museum worked students a taste of what is on offer at the museum. with the newspaper to develop a similar competition over three weeks in February. -

P26 Layout 1

26 Sports Tuesday, December 11, 2018 India end 10-year Australia drought in first-Test thriller Pant helps India win with world record 11 catches ADELAIDE: India won their first Test on Australian soil in SCOREBOARD a decade yesterday, bowling out the home side in a nail- biting finale to clinch the opening match and raise hopes of Scoreboard of the first Test between Australia and their first ever series victory Down Under. India at the Adelaide Oval yesterday: Wicketkeeper Rishabh Pant pouched a world record- equalling 11 catches for the match as India, after setting an improbable target of 323, finally dismissed Australia to win India 1st innings 250 (Pujara 123; Hazlewood 3-52) by 31 runs on day five at Adelaide Oval. Australia 1st innings 235 (Head 72; Bumrah 3-47, Australia, attempting what would have been a record Ashwin 3-57) chase at the ground, gallantly battled to 291 before Josh Hazlewood became the last man to fall to Ravichandran India 2nd innings 307 (Pujara 71, Rahane 70; Lyon 6- Ashwin, who finished with 3-92. Shaun Marsh made 62 122, Starc 3-40) and Tim Paine 41. It was a huge breakthrough for captain Virat Kohli’s Australia 2nd innings (overnight 104-4) men, who went 1-0 up with three Tests to go after becom- ing the first Indian team to win the opening match of a Test A. Finch c Pant b Ashwin 11 series in Australia. Pant took the plaudits after matching M. Harris c Pant b Shami 26 the record of 11 catches in a Test held by England’s Jack U. -

17 May-2020.Qxd

C M C M Y B Y B RNI No: JKENG/2012/47637 Email: [email protected] POSTAL REGD NO- JK/485/2016-18 Internet Edition www.truthprevail.com Truth Prevail Epaper: epaper.truthprevail.com Olympic postponement won't hold back hungry new generation : Gagan Narang 3 5 12 Interventions on to develop horticulture on big Even SC failed to stop employers to pay COVID-19: First Lady Smita Murmu ticket basis in Jammu div : Advisor Sharma wages to employees during lockdown : Bhim visits Quarantine Facility in Samba VOL: 9 Issue: 120 JAMMU AND KASHMIR, SUNDAY , MAY 17, 2020 DAILY PAGES 12 Rs. 2/- IInnssiiddee Govt schedules COVID-19 : JK records 108 new positive cases and 01 death today, 542 cases recovered till date COVID special trains JAMMU, MAY 16 : The cases have been enlisted for 64 recovered (including 01 positive cases with 11 active with 17 active positive and 01 tant to wash your hands regu - lance services 24x7 at their to pick up stranded Government Saturday surveillance which included recovery today); Kupwara has positive cases and 27 recover - recovered while Reasi has 03 larly with soap and water or doorsteps by calling on toll- informed that 108 new posi - 29243 persons in home quar - 97 positive cases (including ies (including 01 recovery positive cases with 02 active clean with alcohol-based hand free number 108 while as JK residents from tive cases of novel antine including facilities 12 reported today) with 49 today) and 01 death; positive and 01 recovered. rub. pregnant women and sick Karnataka, Gujarat, Coronavirus (COVID-19), -

Monday, February 22, 2021 Home-Delivered $1.90, Retail $2.20

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI MONDAY, FEBRUARY 22, 2021 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.20 PAGE 2 FEATURE INSIDE TODAY REMEMBERING PAGES 6-7, 10 DESPERATELY CHRISTCHURCH SEEKING GOLDEN QUAKE JUDY . YEARS 58 YEARS ON SURFING CLASSIC: Open men’s finalist Dylan Barnfield was among the many who converged on Midway’s Pipe break on Saturday for the 26th Makorori First Light Longboarding Surf Classic. The event — the oldest longboarding contest in the country — attracted its largest-ever field, including an excellent response from female surfers. It was changed from Makorori to Midway because of conditions. While it is a contest and there are winners, organisers have always stressed it is more like a festival and the communtity atmosphere underlined this. STORY ON PAGE 2 Picture by Paul Rickard Petition well short Only 722 sign up for referendum on Maori wards here by Alice Angeloni announced an urgent bill to change the Council internal partnerships director establish Maori wards for the 2022 local petition provision, which allows 5 percent James Baty said they had also been elections, five collected enough signatures A MAORI wards petition made of voters to force a public referendum waiting for the petition deadline. to trigger a poll, had the law not been in powerless this month by central with the power to veto a council’s decision. “It’s still a bill, it’s not the process of change. government was about 1000 signatures The Local Electoral (Maori Wards and law yet,” he said. According to Hobson’s short of sending Maori Constituencies) Amendment Bill “Whereas Monday ...today marks the Pledge, 6000 signatures Gisborne to a binding proposes that any demands for a poll will and that date for a valid were collected in poll. -

P17 3 Layout 1

SUNDAY, DECEMBER 25, 2016 SPORTS New Zealand weigh workload worries ahead of ODI series CHRISTCHURCH: New Zealand’s desire tion but coach Mike Hesson is wary Only six players remain from the last played an ODI for New Zealand, but Mustafizur Rahman. Mustafizur took for a confidence-boosting limited overs about the possibility of burnout with squad of 15 who took New Zealand to at domestic level “he has an impressive two wickets in his first competitive series against Bangladesh, starting home series against Australia and South the World Cup final last year and strike-rate and obviously fills the num- match in five months following shoulder tomorrow, has been tempered by the Africa to follow. “It’s always a balancing although the side is rebuilding, selector ber four role with Ross out injured”, surgery while all-rounder Shakib Al need to ease the workloads of Tim act with guys that play all three forms, Gavin Larsen said “it’s very important Larsen said. Ronchi, who did play in the Hasan chimed in with 3-41. Test captain Southee and Trent Boult. especially the bowlers,” Hesson said that we do see improvements during 2015 World Cup, is recalled after a string Mushfiqur Rahim also showed himself in From the high of winning a Test series Saturday, confirming Boult will sit out the home summer”. of low scores saw him dropped from the form with the bat, scoring 45 off 41 against Pakistan in November the switch the last ODI, Southee will miss the three With Ross Taylor sidelined following recent Australia series. -

KT 7-9-2016 .Qxp Layout 1

SUBSCRIPTION WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 7, 2016 THULHIJJA 5, 1437 AH www.kuwaittimes.net MP demands Black Lives Slain Kashmir Maxwell fires ‘sorting’ Matter protesters rebel becomes Australia expatriate shut London what India to world population6 airport12 for hours long14 feared record20 263 Amir pardons prisoners, may Min 33º ‘include political activists’ Max 43º High Tide 02:48 & 15:31 No ban on Twitter MPs seek emergency session Low Tide • 09:27 & 21:29 40 PAGES NO: 16986 150 FILS By B Izzak Polls: Clinton, KUWAIT: HH the Amir Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Sabah yesterday issued a pardon for a number of prisoners who Trump running have served part of their jail terms and reduced the terms of others, on the occasion of Eid Al-Adha. No names were neck and neck mentioned in the brief announcement made by the Amiri Diwan, but activists said it could include political prisoners, WASHINGTON: The race between Hillary Clinton and mostly opposition activists who were handed down jail Donald Trump for the White House has tightened terms for criticizing HH the Amir. But this has not been offi- with two months to go before Election Day, as a series cially confirmed. of new polls yesterday shows them essentially in a Activists said on social media that prominent opposition dead heat. Trump has edged ahead of Clinton in a leader and former MP Musallam Al-Barrak, currently serving new CNN/ORC poll, at 45 percent to 43 percent a two-year jail sentence for insulting HH the Amir, could be among likely voters, while an NBC News poll of regis- pardoned. -

A Glossary of Cricket Terms

A glossary of cricket terms Cricket, more than most sports, is full of expressions and terms designed to bewilder the newcomer (and often even the more seasoned follower). Arm Ball A ball bowled by a slow bowler which has no spin on it and so does not turn as expected but which stays on a straight line ("goes on with the arm") The Ashes Series between England and Australia are played for The Ashes Asking rate - The runs required per over for a team to win - mostly relevant in a one-dayer Ball Red for first-class and most club cricket, white for one-day matches (and, experimentally, women once used blue balls and men orange ones). It weighs 5½ ounces ( 5 ounces for women's cricket and 4¾ ounces for junior cricket) Ball Tampering The illegal action of changing the condition of the ball by artificial means, usually scuffing the surface, picking or lifting the seam of the ball, or applying substances other than sweat or saliva Bat-Pad A fielding position close to the batsman designed to catch balls which pop up off the bat, often via the batsman's pads Batter Another word for batsman, first used as long ago as 1773. Also something you fry fish in Beamer A ball that does not bounce (usually accidently) and passes the batsman at or about head height. If aimed straight at the batsman by a fast bowler, this is a very dangerous delivery (and generally frowned on) Bend your back - The term used to signify the extra effort put in by a fast bowler to obtain some assistance from a flat pitch Belter A pitch which offers little help to bowlers and so heavily favours batsmen Blob A score of 0 (see duck) Bodyline (also known as leg theory) A tactic most infamously used by England in 1932-33, although one which had been around for some time before that, in which the bowler aimed at the batsman rather than the wicket with the aim of making him give a catch while attempting to defend himself. -

YES Or NO? Followed by an Inter National Media Brief Ing

* TODAY: MAN ARRESTED WITH 822 DIAMONDS * RAINS TOO LATE FOR CROF~ * NEW LAWS FOR PRESS * Bringing Africa South R1.00 (GST Inc.) Wednesday March 181992 Live on TV NBC-TV will cross to South Africa at 11 hOO today to bring Namtb- '1an viewers live cov erage of the final results of yesterday's on o landmark referendum In South Africa. This Is scheduled to Include State Presi dent FW de Klerk's address to the nation, YES or NO? followed by an Inter national media brief Ing. * Nation waits with bated breath Coverage will run until about 13hOO. after nailbi'ting finish to poll * For a full report on •A crucial day In the life of South Africa', * Result expected at midday see page 5 CONSERVATIVE REFORMIST GAM. * See also page 3, for SPOll..ER ••• Right BLER ••• National news and views from wing leader Dr ('No') * 'Astonishing' turnout recorded Party leader, State Walvls Bay. Andries Treurnicht President FW de Klerk PIERRE CLAASSEN, SAPA CAPE TOWN: The decisive 1992 all-white ref erendum, probably South Africa's last, ended I.i~;~ last night with polling booths closing on one of JOHANNESBURG: She the most astonishing voter turnopts in the came running out of the country's 82 years of constitutional history. South African airlines of Fears of voter apathy - fa tions had to take the extraordi fice in downtown Johan vouring the No vote - were nary step of providing special nesburgyesterday, but the swept away by queues of vot accommodation for voters still black traffic policeman ers swamping polling booths queueing outside by the 9pm had already hitched the from the far- right northem cut-off time. -

Copy of St-A Ar 2003-04.Pub

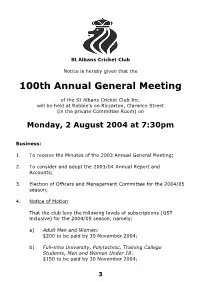

St Albans Cricket Club Notice is hereby given that the 100th Annual General Meeting of the St Albans Cricket Club Inc. will be held at Robbie's on Riccarton, Clarence Street (in the private Committee Room) on Monday, 2 August 2004 at 7:30pm Business: 1. To receive the Minutes of the 2003 Annual General Meeting; 2. To consider and adopt the 2003/04 Annual Report and Accounts; 3. Election of Officers and Management Committee for the 2004/05 season; 4. Notice of Motion That the club levy the following levels of subscriptions (GST inclusive) for the 2004/05 season, namely: a) Adult Men and Women: $200 to be paid by 30 November 2004; b) Full-time University, Polytechnic, Training College Students, Men and Women Under 18: $150 to be paid by 30 November 2004; 3 c) Secondary School Pupils: $100 to be paid by 30 November 2004; d) Primary/Intermediate School Pupils: $40 for first member of family, and $10 for any subsequent members of the same family, to be paid by 30 November 2004; e) Social: $50 to be paid upon joining the club. Please note: there have be no increases in these subscription levels from last season. 5. General Business: Members are reminded to resign (in writing) before the date of the AGM, to ensure that no subscription payment is due for the 2004/05 season, in the event of any member deciding not to play or transferring to another club, or moving out of the city. A light supper will be provided by the club at the conclusion of the AGM. -

Drop Everything

THE PRESS, Christchurch Saturday, May 14, 2011 WEEKENDSPORT D3 RUGBY Crusaders on prowl for ‘leaked’ tries Tony Smith been lost on the Crusaders’ brains Crusaders assistant-coach at length’’ about the potential for Drotske told South African ler and halves Sarel Pretorius and ‘‘But, as long as we’ve got the trust. Daryl Gibson said the Cheetahs exploiting any gaps in the reporters. Tewis de Bruyn are still in the right mindset going into this game, The Crusaders are hoping to Backline director Dan Carter – had been a rejuvenated team since Cheetahs defence. ‘‘But we have beaten them in Cheetahs squad. I think we will be right.’’ exploit the Cheetahs’ propensity to approaching his first game for six returning from their New Zealand But Cheetahs coach Drotske felt the past in Bloemfontein and we Crusaders hooker Corey Flynn, Expect another torrid battle at ‘‘leak tries’’ when they take on the weeks – said while the Cheetahs tour. his charges took a step in the right are going to have another crack at who has had several lively duels the breakdown, especially between high-scoring home team in were ‘‘an extremely dangerous He said their ‘‘open, expansive direction with a much tighter it.’’ with Strauss, agreed the Cheetahs test fetchers Richie McCaw and tomorrow’s Super 15 clash in side, especially at home’’, they also style’’ of back play was comple- defensive display in last week’s The Cheetahs achieved their were a tougher proposition on the Brossow, both back after recent Bloemfontein. ‘‘leak a few tries’’. mented by the ‘‘sheer, brutal 53-14 win over the Lions.