Final Copy of Dissertation 112114

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interview with MO Just Say

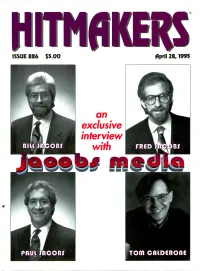

ISSUE 886 $5.00 flpril 28, 1995 an exclusive interview with MO Just Say... VEDA "I Saw You Dancing" GOING FOR AIRPLAY NOW Written and Produced by Jonas Berggren of Ace OF Base 132 BDS DETECTIONS! SPINNING IN THE FIRST WEEK! WJJS 19x KBFM 30x KLRZ 33x WWCK 22x © 1995 Mega Scandinavia, Denmark It means "cheers!" in welsh! ISLAND TOP40 Ra d io Multi -Format Picks Based on this week's EXCLUSIVE HITMEKERS CONFERENCE CELLS and ONE-ON-ONE calls. ALL PICKS ARE LISTED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER. MAINSTREAM 4 P.M. Lay Down Your Love (ISLAND) JULIANA HATFIELD Universal Heartbeat (ATLANTIC) ADAM ANT Wonderful (CAPITOL) MATTHEW SWEET Sick Of Myself (ZOO) ADINA HOWARD Freak Like Me (EASTWEST/EEG) MONTELL JORDAN This Is How...(PMP/RAL/ISLAND) BOYZ II MEN Water Runs Dry (MOTOWN) M -PEOPLE Open Up Your Heart (EPIC) BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN Secret Garden (COLUMBIA) NICKI FRENCH Total Eclipse Of The Heart (CRITIQUE) COLLECTIVE SOUL December (ATLANTIC) R.E.M. Strange Currencies (WARNER BROS.) CORONA Baby Baby (EASTWEST/EEG) SHAW BLADES I'll Always Be With You (WARNER BROS.) DAVE MATTHEWS What Would You Say (RCA) SIMPLE MINDS Hypnotised (VIRGIN) DAVE STEWART Jealousy (EASTWEST/EEG) TECHNOTRONIC Move It To The Rhythm (EMI RECORDS) DIANA KING Shy Guy (WORK GROUP) ELASTICA Connection (GEFFEN) THE JAYHAWKS Blue (AMERICAN) GENERAL PUBLIC Rainy Days (EPIC) TOM PETTY It's Good To Be King (WARNER BRCS.) JON B. AND BABYFACE Someone To Love (YAB YUM/550) VANESSA WILLIAMS The Way That You Love (MERCURY) STREET SHEET 2PAC Dear Mama INTERSCOPE) METHOD MAN/MARY J. BIJGE I'll Be There -

Title "Stand by Your Man/There Ain't No Future In

TITLE "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC by S. DIANE WILLIAMS Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Studies in American Culture Date 98 8AUGUST 15 988AUGUST Firs t Reader Second Reader "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC S. DIANE WILLIAMS AUGUST 15, 19SB TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction - "You Never Called Me By My Name" Page 1 Chapter 1 — "Would Jesus Wear A Rolen" Page 13 Chapter 2 - "You Ain’t Woman Enough To Take My Man./ Stand By Your Man"; Lorrtta Lynn and Tammy Wynette Page 38 Chapter 3 - "Think About Love/Happy Birthday Dear Heartache"; Dolly Parton and Barbara Mandrell Page 53 Chapter 4 - "Do Me With Love/Love Will Find Its Way To You"; Janie Frickie and Reba McEntire F'aqe 70 Chapter 5 - "Hello, Dari in"; Conpempory Male Vocalists Page 90 Conclusion - "If 017 Hank Could Only See Us Now" Page 117 Appendix A - Comparison Of Billboard Chart F'osi t i ons Appendix B - Country Music Industry Awards Appendix C - Index of Songs Works Consulted PREFACE I grew up just outside of Flint, Michigan, not a place generally considered the huh of country music activity. One of the many misconception about country music is that its audience is strictly southern and rural; my northern urban working class family listened exclusively to country music. As a teenager I was was more interested in Motown than Nashville, but by the time I reached my early thirties I had became a serious country music fan. -

MCA Discography

MCA-1 Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan MCA Discography Note: When MCA discontinued Decca, Uni, Kapp and their subsidiary labels in late 1972, they started the new MCA label by consolidating artists from those old labels into the new label. Starting in 1973, MCA reissued hundreds of albums from all of those labels with new catalog numbers under the new MCA imprint. They started these reissues in the MCA-1 reissue series, which ran to MCA-299. MCA MCA-1 Reissue Series: MCA 1 - Loretta Lynn’s Greatest Hits - Loretta Lynn [1973] Reissue of Decca DL7 5000. Don't Come Home A Drinkin'/Before I'm Over You/If You're Not Gone Too Long/Dear Uncle Sam/Other Woman/Wine Women And Song//You Ain't Woman Enough/Blue Kentucky Girl/Success/Home You're Tearin' Down/Happy Birthday MCA 2 - This Is Jerry Wallace - Jerry Wallace [1973] Reissue of Decca DL7 5294. After You/She'll Remember/The Greatest Love/In The Misty Moonlight/New Orleans In The Rain/Time//The Morning After/I Can't Take It Any More/The Hands Of The Man/To Get To You/There She Goes MCA 3 - Rick Nelson in Concert - Rick Nelson [1973] Reissue of Decca DL7 5162. Come On In/Hello Mary Lou, Goodbye Heart/Violets Of Dawn/Who Cares About Tomorrow-Promises/She Belongs To Me/If You Gotta Go, Go Now//I'm Walkin'/Red Balloon/Louisiana Man/Believe What You Say/Easy To Be Free/I Shall Be Released MCA 4 - Sousa Marches in Hi-Fi - Goldman Band [1973] Reissue of Decca DL7 8807. -

Dance Charts Monat 09 / Jahr 2019

Dance Charts Monat 09 / Jahr 2019 Pos. VM Interpret Titel Label Punkte +/- Peak Wo 1 68 SCOTTY THE BLACK PEARL (2020) SPLASHTUNES 3066 +67 1 2 2 52 TECAY ENOUGH FOR ME PUSH2PLAY MUSIC 1947 +50 2 2 3 69 HUGEL HOUSE MUSIC WARNER 1938 +66 3 2 4 143 DRENCHILL FEAT. INDIIANA NEVER NEVER NITRON / SONY 1840 +139 4 2 5 62 MARK GREYHAM GHETTOBLASTER NITRON / SONY 1827 +57 5 2 6 32 ANSTANDSLOS & DURCHGEKNALLT PARTY EP NITRON / SONY 1820 +26 6 2 7 23 SEMITOO PARADISE YOU LOVE DANCE / PLANET 1721 +16 7 2 PUNK MUSIC 8 57 PAUL KALKBRENNER NO GOODBYE SONY 1375 +49 8 2 9 DEEPAIM ON THE EDGE (VIP FESTIVAL EDIT) JAMBACCO RECORDS 1349 0 9 1 10 292 B.INFINITE JEALOUS KHB MUSIC 1338 +282 10 2 11 178 BLAIKZ THE NIGHT MENTAL MADNESS 1291 +167 11 2 12 BROKEN BACK ONE BY ONE (ALLE FARBEN REMIX) SONY 1284 0 8 1 13 CASCADA LIKE THE WAY I DO ZOOLAND 1188 0 7 1 14 GLIDESONIC ENERGY GLIDESONIC PRODUCTIONS 1158 0 9 1 15 152 DJ SNAKE & J BALVIN FEAT. TYGA LOCO CONTIGO GEFFEN RECORDS 1108 +137 15 2 16 30 DAVID GUETTA & MORTEN FEAT. ALOE NEVER BE ALONE WARNER 1094 +14 16 2 BLACC 17 156 KLAAS WHEN WE WERE STILL YOUNG YOU LOVE DANCE / PLANET 1032 +139 17 2 PUNK MUSIC 18 4 RAYMAN RAVE FT. MC DURO THIS IS MY BAY KHB MUSIC 1011 -14 4 2 19 167 SVEN KUHLMANN SUPERNOVA OLAVBELGOE.COM 1005 +148 19 2 20 91 G-LATI & MELLONS FEAT. -

American Dance Band Music Collection Finding Aid (PDF)

American Dance Band Music Collection (UMKC) collection guide: adb = Series I adb2 = Series II Collection Title Composer1 Composer2 Lyricist1 Arranger Publisher Publishing Place Publishing Date Notes adb "A" - you're adorable Kaye, Buddy Wise, Fred Flanagan, Ralph Laurel Music Co., New York, N.Y.: 1948. Lippman, Sidney- comp. adb "Gimme" a little rose Turk, Roy Smith, Jack Bleyer, Archie Irving Berling, Inc., New York, N.Y.: 1926. Pinkard, Macco-comp. adb "High jinks" waltzes Friml, Rudolf Savino, D. G. Schirmer, New York, N.Y.: 1914. adb "Hot" trombone Fillmore, Henry The Fillmore Cincinnati, Oh.: 1921. Bros. Co., adb "March" Arabia Buck, Larry Alford, Harry L. Forster Music Chicago, Ill. : 1914. Publisher Company, adb "Murder," he says McHugh, Jimmy Loesser, Frank Schoen, Vic Paramount Music New York, N.Y.: 1943. Corp., adb "Nelida" three step Eaton, M.B. Lyon & Healy, 1902. adb A La Paree Verdin, Henri Belwin Inc., New York, N.Y.: 1920. adb A Los Toros Salvans, A. Lake, M.L. Carl Fischer, New York, N.Y.: 1921. adb A zut alors-As you please Lamont, Leopold Leo Feist Inc., New York, N.Y.: 1913. adb Aba daba honeymoon Fields, Arthur Donovan, Walter Warrington, Leo. Feist, Inc., New York, N.Y.: 1951. Johnny adb Abie, take an example from Brockman, James O'Hare, W.C. M. Witmark & New York, N.Y.: 1909. inc: If I could gain the your fader Sons, world by wishing adb About a quarter to nine Warren, Harry Dubin, Al Weirick, Paul M. Witmark & New York, N.Y.: 1935. Sons, adb Absence Rosen Sullivan, Alex Barry, Frank E. -

4 Non Blondes – What's Up

4 Non Blondes – What's up [A] [Bm] [D] [A] [A] 25 years of my life and still [Bm] I'm trying to get up that great big hill of [D] hope for a [A] destination I realized quickly when I knew I should that the world was made of this brotherhood of man for whatever that means And so I cry sometimes when I'm lying in bed Just to get it all out what's in my head, and I, I am feeling a little peculiar. And so I wake in the morning and I step outside And I take a deep breath and I get real high And I scream from the top of my lungs : “What's going on?” And I say: Hey yeah yeah yeah yeah Hey yeah yeah I said hey: “What's going on?“ And I say: Hey yeah yeah yeah yeah Hey yeah yeah I said hey: “What's going on?“ Uhh, uh, uhuhuh uhuhuh Uhh, uh, uhuhuh uhuhuh And I try oh my god do I try, I try all the time In this institution And I pray oh my god do I pray, I pray every single day for a revolution. And so I cry sometimes when I'm lying in bed Just to get it all out what's in my head and I, I am feeling a little peculiar. And so I wake in the morning and I step outside And I take a deep breath and I get real high And I scream from the top of my lungs : “What's going on?” REFRAIN 2x 25 years of my life and still I'm trying to get up that great big hill of hope for a destination Abba – Winner takes it all I don't wanna [D] talk about the things we've gone [A] through Though it's hurting [Em] me, now it's [A] history I've played all my [D] cards and that's what you've done [A] too Nothing more to [Em] say, no more ace to [A] play The winner takes it [D] all, The loser standing [Bm] small Beside the [Em] victory that's her [A] destiny I was in your [D] arms thinking I belonged [A] there I figured it made [Em] sense building me a [A] fence Building me a [D] home thinking I'd be [A] strong there But I was a [Em] fool playing by the [A] rules The gods may throw a [D] dice, their minds as cold as [Bm] ice And someone way down [Em] here loses someone [A] dear The winner takes it [D] all, the loser has to [Bm] fall It's simple and it's [Em] plain. -

A Translation Into English of the German Novel Jakob Der Lügner By

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1983 A translation into English of the German novel Jakob der Lugner̈ by Jurek Becker Harriet Passell Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the German Literature Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Passell, Harriet, "A translation into English of the German novel Jakob der Lugner̈ by Jurek Becker" (1983). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3258. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.3249 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Harriet Passell for the Master of Arts in German presented October 21~ 1983. Title: A translation into English of the German novel Jakob der Lugner by Jurek Becker. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Franz Langha11111er, cOlJiSE1teto p;.. This thesis is a translation of the German novel Jakob der Lugnerl by Jurek Becker. In my commentary I have tried to explain why I undertook the project of translating this novel from German into English, when that had already been done by Melvin Kornfeld.2 Kornfeld's translation, which is no longer in print, fails to do justice lJurek Becker, Jakob der Lugner, (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1980). 2Jurek Becker, Jacob The Liar, trans. Melvin Kornfeld (New York and London: Harcourt Brace Javanovich, 1975). -

Missionary Supplement Our God Is Able

; I I I The Baptist Herald A DENOMINATIONAL PAPER VOICIN G THE INTERESTS OF THE GERMAN BAPTIST YOUNG PEOPLE'S AND SUNDAY SCHOOL WORKERS' UNION Volume Nine CLEVELAND, 0 ., FEBRUARY 1, 1931 Number Three Missionary Supplement Our God Is Able To save us unto the uttermost; To keep that which we have commit- ted unto him; To deliver us; To raise us up; even from the dead; To make us stand; To succor them that are tempted; To subdue all things unto himself; To perform that which he has prom- ised; To make all grace abound; To do exceeding abundantly above all that we ask or think; To keep us from falling, and to pre sent us faultless before the presence of his glory with exceeding joy. 2 THE BAPTIST HERALD February 1, 1931 8 What's f}appening Rev. Philip Potzner, pastor of the year. Pastor W. H. Barsch baptized two nicely, having an enrollment on January The Baptist Herald First Church of Leduc, Alta., Can., bas adults and extended the band of fellow 11 of 326 and an attendance of 301 with r esigned and closed his work there with ship to them. The service was greatly no other attraction than the usual 'study the fatter part of January. enriched with special music by Mrs. Caro period. This is the largest enrollment it Do It Now "Advertising is the education of the public as line Barsch and Mrs. Albert Fienemann. to who you are, where you are, and what you have The Missionary Supplement in this ever had, and 801 is to date an attend F with pleasure you are viewing any work a man Re.v ..Gu stave Friedenberg brought the ance record. -

1 What You Need to Know About the AP Psychology Exam, 3 2 How to Plan Your Time, 9

5 STEPS TO A 5 AP Psychology 2010–2011 Laura Lincoln Maitland, M.A., M.S. New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto Copyright © 2010 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All r.ights reserved. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-07-162453-4 MHID: 0-07-162453-8 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: ISBN: 978-0-07-162454-1, MHID: 0-07-162454-6. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial- fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. To contact a representa- tive please e-mail us at [email protected]. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“McGraw-Hill”) and its licensors reserve all rights in and to the work. Use of this work is subject to these terms. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976 and the right to store and retrieve one copy of the work, you may not decompile, disassemble, reverse engineer, reproduce, modify, create derivative works based upon, transmit, distribute, disseminate, sell, publish or sublicense the work or any part of it without McGraw-Hill’s prior consent. -

Dance Charts Monat 11 / Jahr 2019

Dance Charts Monat 11 / Jahr 2019 Pos. VM Interpret Titel Label Punkte +/- Peak Wo 1 5 TONES AND I DANCE MONKEY ELEKTRA 4194 +4 1 3 2 33 ROCKSTROH & SEAN FINN SCHMETTERLINGE SELFIE TUNES 3726 +31 2 2 3 6 ARNOLD PALMER & CJ STONE SUNSHINE YOU LOVE DANCE / PLANET 3534 +3 3 2 PUNK MUSIC 4 66 FRITZ KALKBRENNER KINGS & QUEENS NASUA 3291 +62 4 2 5 116 STEREOACT FEAT. VANESSA MAI JA NEIN VIELLEICHT SONY 2881 +111 5 2 6 3 SUNNY MARLEEN & ALEX ALIVE LIKE LOVE MENTAL MADNESS 2655 -3 3 3 7 18 BLAIKZ WORLD OF DREAMS MENTAL MADNESS 2318 +11 7 2 8 140 CAPPELLA MOVE ON BABY (MIKE CANDYS REMIX) ZYX 2269 +132 8 2 9 SEMITOO, MARC KORN & MARC CROWN HIT THE LIGHT YOU LOVE DANCE / PLANET 2221 0 9 1 PUNK MUSIC 10 40 DJ GOLLUM & A. SPENCER IN THE SHADOWS 2K19 GLOBAL AIRBEATZ 2219 +30 10 2 11 103 RENE PARK TRIP TO RED PLANET MELLOWAVE RECORDS 1975 +92 11 2 12 11 ROBIN SCHULZ & NICK MARTIN & SAM RATHER BE ALONE WARNER 1935 -1 11 3 MARTIN 13 127 MEDUZA & BECKY HILL FEAT. GOODBOYS LOSE CONTROL UNIVERSAL 1912 +114 13 2 14 34 FLOORFILLA X PHATT LENNY ANTHEM #4 SHOONZ 1902 +20 14 2 15 188 JASON PARKER VOYAGE VOYAGE MENTAL MADNESS 1813 +173 15 2 16 10 HOUSEFLY I'M OVER YOU TB MEDIA 1797 -6 10 3 17 69 CALMANI & GREY FEAT. ONIVA TAKE ME BACK KNIGHTVISION 1773 +52 17 2 18 DAN KERS BACK IN USA MENTAL MADNESS 1648 0 13 1 19 91 BADETASCHE SATURDAY NIGHT TOKA BEATZ 1436 +72 19 2 20 20 JASON D3AN FEEL BETTER FADERSPORT 1328 0 20 3 21 82 JEROME LIGHT KONTOR 1297 +61 21 4 22 26 M4RO & JON THOMAS FEAT. -

TV Crew Visit LC to See What Is

January 23, 2008 Issue 4 ire Lewis Central High School 3504 Harry Langdon Blvd. Council Bluffs, IA 51503 the TV Crew VisitW LC to See What is “Cool” On Tuesday, January 8th, a local news team from Channel 6 stormed the building looking for talent and diversity for a segment titled High School Cribs. They didn’t have to go far to find what made Lewis Central cool. WOWT Channel 6 Morning news anchor Malorie Maddox and photojournalist Nathan Jank were very impressed with the opportu- nities available to the students at our school. “It’s amazing to see 70% Lindsey Lawrence of the student body getting involved in extra-curricular activities,” Business Editor said Maddox. Pottery, Jazz Band and Corporation were among the six classes chosen for filming. “I think Lewis Central is unique with its incredible pottery lab,” said Maddox, “Students were busy showing their creativity the entire time we were there, and the fin- ished products were incredibly beautiful and diverse.” Jazz Band and Corporation put on a performance for the crew. The camera focused on group shots as well as individual performances throughout both segments of the video. The band performed Nostalgia in Time Square and Corporation sang We Still Have Time accompa- nied by the Corporation Band. “I think this will be good recognition for our school,” said sophomore Lauren Petri. “It’s impressive, Lewis Central students have so much pride in their school, they are will- ing to spend time after school to participate in programs.” said Maddox.“Plus, many of Lewis Central’s programs are growing, because students are encouraging others to get involved.” Introduction to Engineering and Design, PC Support, Auto-Cad, and members of Project Lead the Way were also featured. -

Dance Charts Monat 10 / Jahr 2019

Dance Charts Monat 10 / Jahr 2019 Pos. VM Interpret Titel Label Punkte +/- Peak Wo 1 4 DRENCHILL FEAT. INDIIANA NEVER NEVER NITRON / SONY 4326 +3 1 3 2 24 HUGEL GUAJIRA GUANTANAMERA WARNER 3309 +22 2 2 3 44 SUNNY MARLEEN & ALEX ALIVE LIKE LOVE MENTAL MADNESS 2872 +41 3 2 4 1 SCOTTY THE BLACK PEARL (2020) SPLASHTUNES 2794 -3 1 3 5 102 TONES AND I DANCE MONKEY ELEKTRA 2690 +97 5 2 6 ARNOLD PALMER & CJ STONE SUNSHINE YOU LOVE DANCE / PLANET 2521 0 3 1 PUNK MUSIC 7 11 BLAIKZ THE NIGHT MENTAL MADNESS 2474 +4 7 3 8 8 PAUL KALKBRENNER NO GOODBYE SONY 2093 0 8 3 9 21 DANKY CIGALE & SYDNEY-7 BOOM BOOM KHB MUSIC 2091 +12 9 2 10 149 HOUSEFLY I'M OVER YOU TB MEDIA 1875 +139 10 2 11 77 ROBIN SCHULZ & NICK MARTIN & SAM RATHER BE ALONE WARNER 1824 +66 11 2 MARTIN 12 7 SEMITOO PARADISE YOU LOVE DANCE / PLANET 1740 -5 7 3 PUNK MUSIC 13 47 VAN EDELSTEYN JAMES BROWN IS DEAD ZYX MUSIC 1678 +34 13 3 14 2 TECAY ENOUGH FOR ME PUSH2PLAY MUSIC 1672 -12 2 3 15 13 CASCADA LIKE THE WAY I DO ZOOLAND 1658 -2 13 2 16 10 B.INFINITE JEALOUS KHB MUSIC 1487 -6 10 3 17 128 NEPTUNICA FEAT. EMY PEREZ THAT SATURDAY KONTOR 1454 +111 17 2 18 BLAIKZ WORLD OF DREAMS MENTAL MADNESS 1450 0 7 1 19 9 DEEPAIM ON THE EDGE (VIP FESTIVAL EDIT) JAMBACCO RECORDS 1443 -10 9 2 20 62 JASON D3AN FEEL BETTER FADERSPORT 1359 +42 20 2 21 23 LUM!X & GABRY PONTE MONSTER (ROBIN SCHULZ REMIX) SPINNIN / WARNER 1325 +2 21 2 22 186 NIELS VAN GOGH LIKE A BULLET BIG BLIND MUSIC 1323 +164 22 2 23 22 ANDREW SPENCER & BLACKBONEZ BEAUTIFUL NIGHTS MENTAL MADNESS 1319 -1 22 3 24 6 ANSTANDSLOS & DURCHGEKNALLT PARTY EP NITRON / SONY 1293 -18 6 3 25 14 GLIDESONIC ENERGY GLIDESONIC PRODUCTIONS 1268 -11 14 2 26 90 M4RO & JON THOMAS FEAT.