How Geoscience Novices Reason About Temporal Duration: the Role of Spatial Thinking and Large Numbers Kim A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

User's Guide 5636 (MTG)

MA2006-EA © 2020 CASIO COMPUTER CO., LTD. User’s Guide 5636 (MTG) ENGLISH Congratulations upon your selection of this CASIO watch. To ensure that this watch provides you with the years of service for which it is designed, carefully For details about how to use this watch and for read and follow the instructions in this manual, troubleshooting information, go to the website especially the information under “Operating below. Precautions” and “User Maintenance”. Be sure to keep all user documentation handy https://world.casio.com/manual/wat/ for future reference. x Keep the watch’s face exposed to light as much as possible (page E-5). Important! x For details about how to adjust the current time zone, time, and day settings, see “Timekeeping (Current Time and Day Adjustment)” (page E-6). E-1 Features The Bluetooth® word mark and logos are registered trademarks owned by Bluetooth SIG, Inc. and any use of such marks by CASIO COMPUTER CO., LTD. is under license. Your watch provides you with the features and functions described below. This product has a Mobile Link function that lets it communicate with a Bluetooth® capable phone to perform automatic time adjustment and other operations. ◆ Solar powered operation ........................................................................................Page E-5 x This product complies with or has received approval under radio laws in various countries and The watch generates electrical power from sunlight and other types of light, and uses it to charge a geographic areas. Use of this product in an area where it does not conform to or where it has not battery that powers operation. -

Time Perception 1

TIME PERCEPTION 1 Time Perception: A Review on Psychological, Computational and Robotic Models Hamit Basgol, Inci Ayhan, and Emre Ugur Abstract—Animals exploit time to survive in the world. Tem- Learning to Time Prospective Behavioral Timing poral information is required for higher-level cognitive abilities Algorithmic Level Encoding Type Theory of Timing Retrospective such as planning, decision making, communication, and effective Internal Timing cooperation. Since time is an inseparable part of cognition, Clock Theory there is a growing interest in the artificial intelligence approach Models Abilities to subjective time, which has a possibility of advancing the field. The current survey study aims to provide researchers Dedicated Models with an interdisciplinary perspective on time perception. Firstly, Implementational Time Perception Sensory Timing Level Modality Type we introduce a brief background from the psychology and Intrinsic Models in Natural Motor Timing Cognitive neuroscience literature, covering the characteristics and models Systems of time perception and related abilities. Secondly, we summa- Language rize the emergent computational and robotic models of time Multi-modality Action perception. A general overview to the literature reveals that a Relationships Characteristics Multiple Timescales Decision Making substantial amount of timing models are based on a dedicated Scalar Property time processing like the emergence of a clock-like mechanism Magnitudes from the neural network dynamics and reveal a relationship between the embodiment and time perception. We also notice Fig. 1. Mind map for natural cognitive systems of time perception that most models of timing are developed for either sensory timing (i.e. ability to assess an interval) or motor timing (i.e. -

From Relativistic Time Dilation to Psychological Time Perception

From relativistic time dilation to psychological time perception: an approach and model, driven by the theory of relativity, to combine the physical time with the time perceived while experiencing different situations. Andrea Conte1,∗ Abstract An approach, supported by a physical model driven by the theory of relativity, is presented. This approach and model tend to conciliate the relativistic view on time dilation with the current models and conclusions on time perception. The model uses energy ratios instead of geometrical transformations to express time dilation. Brain mechanisms like the arousal mechanism and the attention mechanism are interpreted and combined using the model. Matrices of order two are generated to contain the time dilation between two observers, from the point of view of a third observer. The matrices are used to transform an observer time to another observer time. Correlations with the official time dilation equations are given in the appendix. Keywords: Time dilation, Time perception, Definition of time, Lorentz factor, Relativity, Physical time, Psychological time, Psychology of time, Internal clock, Arousal, Attention, Subjective time, Internal flux, External flux, Energy system ∗Corresponding author Email address: [email protected] (Andrea Conte) 1Declarations of interest: none Preprint submitted to PsyArXiv - version 2, revision 1 June 6, 2021 Contents 1 Introduction 3 1.1 The unit of time . 4 1.2 The Lorentz factor . 6 2 Physical model 7 2.1 Energy system . 7 2.2 Internal flux . 7 2.3 Internal flux ratio . 9 2.4 Non-isolated system interaction . 10 2.5 External flux . 11 2.6 External flux ratio . 12 2.7 Total flux . -

The Time Wave in Time Space: a Visual Exploration Environment for Spatio

THE TIME WAVE IN TIME SPACE A VISUAL EXPLORATION ENVIRONMENT FOR SPATIO-TEMPORAL DATA Xia Li Examining Committee: prof.dr.ir. M. Molenaar University of Twente prof.dr.ir. A.Stein University of Twente prof.dr. F.J. Ormeling Utrecht University prof.dr. S.I. Fabrikant University of Zurich ITC dissertation number 175 ITC, P.O. Box 217, 7500 AE Enschede, The Netherlands ISBN 978-90-6164-295-4 Cover designed by Xia Li Printed by ITC Printing Department Copyright © 2010 by Xia Li THE TIME WAVE IN TIME SPACE A VISUAL EXPLORATION ENVIRONMENT FOR SPATIO-TEMPORAL DATA DISSERTATION to obtain the degree of doctor at the University of Twente, on the authority of the rector magnificus, prof.dr. H. Brinksma, on account of the decision of the graduation committee, to be publicly defended on Friday, October 29, 2010 at 13:15 hrs by Xia Li born in Shaanxi Province, China on May 28, 1977 This thesis is approved by Prof. Dr. M.J. Kraak promotor Prof. Z. Ma assistant promoter For my parents Qingjun Li and Ruixian Wang Acknowledgements I have a thousand words wandering in my mind the moment I finished this work. However, when I am trying to write them down, I lose almost all of them. The only word that remains is THANKS. I sincerely thank all the people who have been supporting, guiding, and encouraging me throughout my study and research period at ITC. First, I would like to express my gratitude to ITC for giving me the opportunity to carry out my PhD research. -

Instructions Digital Atomic Watch

Instructions Digital Atomic Watch Introducing by ARCRON the world’s most accurate time keeping technology This wrist watch is a radio-controlled watch with SyncTime technology. A quartz oscillator, like most other modern clocks drives it. It has a built-in receiver to pick up the time signal broadcast from the U.S. Atomic Clock, which is operated by the National Institute of Science and Technology (NIST). This time protocol performs an internal check and, should any changes be necessary (e.g. Daylight Saving Time), corrects its internal time immediately. This check is carried out every day. This precise time information is also used to calibrate the internal oscillator, a feature only found in SyncTime time pieces. For these time pieces it is sufficient if a signal is received only every now and then. This gives you the added advantage of having the precise time even when traveling outside North America. SyncTime time pieces still run much more accurate than ordinary quartz clocks or even other radio-controlled clocks. Functions Your Chrono offers the following features: 1. Local Time in hours/minutes/seconds + Time Zone Indicator Date as Day of the week/month/day or World Time as UTC in h/min 2. Alarm 3. Date Alert The date alert is a silent alarm that flashes on the watch display on the day set, it continues to flash the entire day. 4. Time Zone display in three different ways: - indicator pointing to Time Zone in map - deviation from UTC in hours - Local Time in h/min/sec (manual adjustment to Daylight Saving Time possible) 5. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Factors Underlying Students' Conceptions of Deep Time: An Exploratory Study CHEEK, KIM How to cite: CHEEK, KIM (2010) Factors Underlying Students' Conceptions of Deep Time: An Exploratory Study, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/277/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk FACTORS UNDERLYING STUDENTS’ CONCEPTIONS OF DEEP TIME: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY By Kim A. Cheek ABSTRACT Geologic or “deep time” is important for understanding many geologic processes. There are two aspects to deep time. First, events in Earth’s history can be placed in temporal order on an immense time scale (succession). Second, rates of geologic processes vary significantly. Thus, some events and processes require time periods (durations) that are outside a human lifetime by many orders of magnitude. Previous research has demonstrated that learners of all ages and many teachers have poor conceptions of succession and duration in deep time. -

A History of Rhythm, Metronomes, and the Mechanization of Musicality

THE METRONOMIC PERFORMANCE PRACTICE: A HISTORY OF RHYTHM, METRONOMES, AND THE MECHANIZATION OF MUSICALITY by ALEXANDER EVAN BONUS A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2010 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of _____________________________________________________Alexander Evan Bonus candidate for the ______________________Doctor of Philosophy degree *. Dr. Mary Davis (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) Dr. Daniel Goldmark ________________________________________________ Dr. Peter Bennett ________________________________________________ Dr. Martha Woodmansee ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) _______________________2/25/2010 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Copyright © 2010 by Alexander Evan Bonus All rights reserved CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES . ii LIST OF TABLES . v Preface . vi ABSTRACT . xviii Chapter I. THE HUMANITY OF MUSICAL TIME, THE INSUFFICIENCIES OF RHYTHMICAL NOTATION, AND THE FAILURE OF CLOCKWORK METRONOMES, CIRCA 1600-1900 . 1 II. MAELZEL’S MACHINES: A RECEPTION HISTORY OF MAELZEL, HIS MECHANICAL CULTURE, AND THE METRONOME . .112 III. THE SCIENTIFIC METRONOME . 180 IV. METRONOMIC RHYTHM, THE CHRONOGRAPHIC -

Reflection of Time in Postmodern Literature

Athens Journal of Philology - Volume 2, Issue 2 – Pages 77-88 Reflection of Time in Postmodern Literature By Tatyana Fedosova This paper considers key tendencies in postmodern literature and explores the concept of time in the literary works of postmodern authors. Postmodern literature is marked with such typical features as playfulness, pastiche or hybridity of genres, metafiction, hyper- reality, fragmentation, and non-linear narrative. Quite often writers abandon chronological presentation of events and thus break the logical sequence of time/space and cause/effect relationships in the story. Temporal distortion is used in postmodern fiction in a number of ways and takes a variety of forms, which range from fractured narratives to games with cyclical, mythical or spiral time. Temporal distortion is employed to create various effects: irony, parody, a cinematographic effect, and the effect of computer games. Writers experiment with time and explore the fragmented, chaotic, and atemporal nature of existence in the present. In other words, postmodern literature replaces linear progression with a nihilistic post-historical present. Almost all of these characteristics result from the postmodern philosophy which is oriented to the conceptualization of time. In postmodernism, change is fundamental and flux is normal; time is presented as a construction. A special attention in the paper is paid to the representation of time in Kurt Vonnegut’s prose. The author places special emphasis on the idea of time, and shifts in time become a remarkable feature of his literary work. Due to the dissolution of time/space relations, where past, present, and future are interwoven, the effect of time chaos is being created in the author’s novels, which contribute to his unique individual style. -

Timing Life Processes

1st International Conference on Advancements of Medicine and Health Care through Technology, MediTech2007, 27-29th September, 2007, Cluj-Napoca, ROMANIA Timing Life Processes Dana Baran Abstract — Natural clocks such as planet movements and biological timekeeping gears inspired artificial timers including water clocks, sandglasses, mechanical, electric and finally electronic systems. Contemporary medicine and biology reconsiders temporal morphogenetic and functional patterns interpreting life processes as highly sophisticated clockworks, liable to mathematical modelling and quantification. Chronobiology and chronomedicine opened a vast theoretical and applicative field of interest. Keywords: chronobiology, temporal monitoring devices, biological clock, mathematical modelling. 1. INTRODUCTION exogenous synchronizers periodically adjust to the cosmic time. [2] At the very beginning, breathing and heart rate, Throughout the centuries the perspective on biological pulse frequency, menstrual cycles and vital forces were phenomena temporal dimension, i.e. on their dynamic perceived as led by rhythmic vibrations of the stars, the sun structure and function, followed several synchronic and and the moon. Nature exhibited both clocks and calendars! diachronic patterns, possibly defined as astromy Now living beings are usually forced to disrupt their innate thological, cosmobiological, mechanistic, physico- biorhythms and adapt to man-made temporal cues imposed chemical, statistico-mathematical, physiological, psy by shift work, jet travel, abundance of vegetables and chological or philosophical insights. [1] After 1950, animal products, irrespective of time of day or season, in scientists started to elaborate a coherently integrated vitro fertilization, cloning and genetic manipulation which multidisciplinary and even transdisciplinary approach to equally play with biological time and social destinies. biological rhythms. Largely known as chronobiology, it lately generated a medical subdivision: chronomedicine. -

TIME out Who Weighed About Three Hundred and fifty Pounds and His Two Grocery Carts Crammed with Bags of Tostitos and Bot- Confessions of a Watch Geek

ELECTRONICALLY REPRINTED FROM MARCH 20, 2017 rence. Since turning forty, I’d started to PERSONAL HISTORY suffer from a heightened sense of claus- trophobia. A few years ago, I was stuck for an hour in an elevator with a man TIME OUT who weighed about three hundred and fifty pounds and his two grocery carts crammed with bags of Tostitos and bot- Confessions of a watch geek. tles of Canada Dry, an experience both BY GARY SHTEYNGART frightening and lonely. The elevator had simply given up. What if a subway train also refused to move? I began walking seventy blocks at a time or splurging on taxis. But on this day I had taken the N train. Somewhere between Forty- ninth Street and Forty-second Street, a signal failed and we ground to a halt. For forty minutes, we stood still. An old man yelled at the conductor at full vol- ume in English and Spanish. Time and space began to collapse around me. The orange seats began to march toward each other. I was no longer breathing with any regularity. This is not going to end well. None of this will end well. We will never leave here. We will always be underground. This, right here, is the rest of my life. I walked over to the conduc- tor’s silver cabin. He was calmly explain- ing to the incensed passenger the scope of his duties as an M.T.A. employee. “Sir,” I said to him, “I feel like I’m dying.” “City Hall, City Hall, we got a sick passenger,” he said into the radio. -

Time Perception and Age Percepção Do Tempo E Idade Vanessa Fernanda Moreira Ferreira, Gabriel Pina Paiva, Natália Prando, Carla Renata Graça, João Aris Kouyoumdjian

DOI: 10.1590/0004-282X20160025 ARTICLE Time perception and age Percepção do tempo e idade Vanessa Fernanda Moreira Ferreira, Gabriel Pina Paiva, Natália Prando, Carla Renata Graça, João Aris Kouyoumdjian ABSTRACT Our internal clock system is predominantly dopaminergic, but memory is predominantly cholinergic. Here, we examined the common sensibility encapsulated in the statement: “time goes faster as we get older”. Objective: To measure a 2 min time interval, counted mentally in subjects of different age groups. Method: 233 healthy subjects (129 women) were divided into three age groups: G1, 15-29 years; G2, 30-49 years; and G3, 50-89 years. Subjects were asked to close their eyes and mentally count the passing of 120 s. Results: The elapsed times were: G1, mean = 114.9 ± 35 s; G2, mean = 96.0 ± 34.3 s; G3, mean = 86.6 ± 34.9 s. The ANOVA-Bonferroni multiple comparison test showed that G3 and G1 results were significantly different (P < 0.001).Conclusion: Mental calculations of 120 s were shortened by an average of 24.6% (28.3 s) in individuals over age 50 years compared to individuals under age 30 years. Keywords: time perception; age; timing; aging. RESUMO Nosso sistema de relógio interno é predominantemente dopaminérgico, mas a memória é predominantemente colinérgica. Neste estudo, examinamos a assertiva comum que “o tempo passa mais rápido para pessoas mais velhas”. Objetivo: Medir o intervalo de tempo 2 min contados mentalmente em pessoas de diferentes faixas etárias. Método: 233 pessoas saudáveis (129 mulheres) foram divididos em três grupos: G1, 15-29 anos; G2, 30-49 anos; e G3, 50-89 anos. -

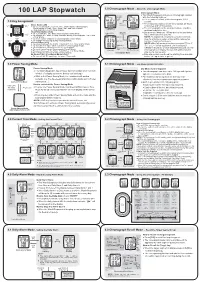

100 LAP Stopwatch

5.0 Chronograph Mode - About the Chronograph Mode 100 LAP Stopwatch Chronograph Mode ● This Watch/Stopwatch includes a chronograph function with the following features: ● The measurement unit of the chronograph: 1/100 1.0 Key Assignment second. ● The measuring capacity of the chronograph: 23 hours, Mode Button [M] ● To select among the Current Time, Daily Alarm, Chronograph, 59 minutes and 59.99 seconds. Chronograph Recall, Timer, Dual Time and Pacer Mode. ● The Chronograph can be used to measure: Lap time, ● Hold down to select setting display. split time/cumulative time. Start/Stop Button [S/S] ● Lap memory: Maximum 100 lap memories (see below ● To Turn ON/OFF the daily alarm in Daily Alarm Mode. ● To activate the 'start' or 'stop' function during Chronograph, Timer and note); Maximum 30 segments. Pacer Mode. NOTE: As registered a segment consumes memory, ● To recall target segment in Chronograph Recall Mode. thus the effective number of laps will be reduced as ● To change the setting during setting display. number of segment increases. Reset Button [L/R] ● To select between the Alarm 1 and Alarm 2 in Daily Alarm Mode. NOTE: When all memory has been occupied ('Free 0', ● To activate the 'lap' / 'save' function in Chronograph Mode. 'S--', or 'L---' will be appeared), the chronograph ● To activate the 'reload' function in Timer Mode. CANNOT record lap or save segment anymore, i.e.The ● To recall target lap in Chronograph Recall Mode. chronograph can display the lap and split/cumulative ● To select between the Timer 1 and Timer 2 in Timer Mode. ● To change the setting during setting display.