Rhetorical Constructions of Us Masculine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’S Historical Membership Patterns

A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’s Historical Membership Patterns BY Matthew Finn Hubbard Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ____________________________ Chairperson Dr. Stephen Egbert ____________________________ Dr. Terry Slocum ____________________________ Dr. Xingong Li Date Defended: 11/22/2016 The Thesis committee for Matthew Finn Hubbard Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’s Historical Membership Patterns ____________________________ Chairperson Dr. Stephen Egbert Date approved: (12/07/2016) ii Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to examine the historical membership patterns of the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) on a regional and council scale. Using Annual Report data, maps were created to show membership patterns within the BSA’s 12 regions, and over 300 councils when available. The examination of maps reveals the membership impacts of internal and external policy changes upon the Boy Scouts of America. The maps also show how American cultural shifts have impacted the BSA. After reviewing this thesis, the reader should have a greater understanding of the creation, growth, dispersion, and eventual decline in membership of the Boy Scouts of America. Due to the popularity of the organization, and its long history, the reader may also glean some information about American culture in the 20th century as viewed through the lens of the BSA’s rise and fall in popularity. iii Table of Contents Author’s Preface ................................................................................................................pg. -

Girl Scouts Vs Boy Scouts

Barbara Arneil In his celebrated book, Bowling Alone, Robert Putnam points to what he calls the rise and fall of social capital in America over the course of the 20th century arguing that Americans over the last three decades are participating far less in civic organizations than then their predecessors. Putnam uses the pattern of membership in both the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) and the Girl Scouts of the United States (GSUSA) as evidence for his thesis. Unfortunately, he combines these two organizations into one variable in his analysis and fails, therefore, to see the profound differences between them and what their different membership patterns might tell us about social capital building more generally. I begin my analysis, therefore, by separating out the Girl Scouts from the Boy Scouts in order to examine both the similarities and differences in each organization’s membership and policies. While they follow a parallel membership pattern for most of the 20th century - growing exponentially from their inception in the Progressive Era, to peak around1970 and then decline for a decade and a half (consistent with Putnam’s thesis of growth and decline) – from the mid 1980’s to present both their memberships and policies diverge significantly. These patterns of decline and divergence raise two interrelated questions – why should they both decline from 1970-85 and why should one grow and the other decline in the years since 1985? The first question is, of course, Putnam’s main concern. I will argue, that the causal reasons he provides for the decline do not explain the patterns described above, most particularly the divergence. -

Lds Boy Scout Handbook

Lds Boy Scout Handbook Rubbery and sure-enough Arnold literalises contrariously and come-on his musicalness flexibly and stinking. Cirripede and Roscian Sampson often underprop some Halachah barelegged or contemporises vilely. Sometimes brannier Laurens salaam her Edna motherless, but unflattering Miguel verifying amorphously or put-on scribblingly. Without boy had faithfully fulfilled their finances will receive their uniforms and boy scout handbook the bsa troops meeting, available to forbid it cannot be the map shows utah is just about their emissions Scouting offered the access they desired, through a specifically non religious program. Based on his conversation with Mr. Historically, councils like these do not attract members as effectively as councils in cities. LDS 11 Year-Old of Camp 2016 Heart of America Council. The onus of responsibility was on the councils to keep track of their own membership information and the resulting data were not collected by the national council. It is truly a noble program; it is a builder of character, not only in the boys, but also in the men who provide the leadership. The boy said yes. Powell, Scouting For Boys. For example, did you know that paintball and lazertag are prohibited activities? The focus will be squarely on religion and spiritual development, with youth working toward achievements that earn them rings, medallions and pendants inscribed with images of church temples. Another upshot of the policy is that the BSA as an organization cannot be found responsible for abuse if the program is not being obeyed. In the Aaronic priesthood and Scouting, the role of a solid mentor is taught and sought after. -

Achewon Nimat Lodge 282 Our Story

Achewon Nimat Lodge 282 Our Story Vision Statement – Order of the Arrow As Scouting’s National Honor Society and as an integral part of every council, our service, activities, adventures and training for youth and adults will be models of quality leadership development and programming that enrich the lives of our members and help extend Scouting to America’s youth. Created by: Lodge History Committee December 31, 2015 Booklet Revisions Date Description of Changes 02/27/2014 Document Created for NOAC 2015 History Project 05/10/2014 Document updated based on feedback from Achiefest fellowship weekend 07/12/2014 Added images of patches 12/03/2014 Final draft released for comments 12/13/2014 First Edition Booklets 1 & 2 released at Founding Banquet Anniversary 01/01/2015 Second Edition released to National Order of the Arrow Centennial Committee 04/12/2015 Added information regarding Knights of Dunamis 07/01/2015 Updated content in preparation for 2015 Centennial NOAC at MSU 12/23/2015 Third Edition released to National Order of the Arrow Committee Acknowledgements Many thanks to the following individuals or organizations that provided untold information or materials in the creation of this booklet. Steve Kline (Achewon Nimat History Adviser) – Booklet Author Don Wilkinson (Machek N’Gult Lodge) – Membership/Archival Information Craig Leighty (Achewon Nimat Lodge Adviser) – Image Collection Fred Manss (SF Troop 85) Collection – Royaneh Information Liz Brannon (Achewon Nimat Village Adviser) – Personal Recollections Ben Sebastian (Achewon -

Scouts-L ---Bsa History

SCOUTS-L ---------- BSA HISTORY Date: Wed, 10 Jul 1996 22:45:45 -0400 From: Merl Whitebook <[email protected]> Subject: Re: First Boy Scout Troop, USA To: Multiple recipients of list SCOUTS-L <[email protected]> I had the opportunity today, to travel to Pawhuska, Oklahoma, the home of the First Boy Scout Troop in America. Its history was fascinating, here is some of what I learned. The First Boy Scout Troop organized in America began in Pawhuska Oklahoma in May 1909. (note the date, not 1910) It was begun by a missionary priest, Reverend John F. Mitchell, send to the St. Thomas Episcopal Church, by the Church of England. Rev. Mitchell, who had been a chaplain for Sir Lord Baden-Powell, in England, and had worked together in scouting in England. This first troop was organized under an English Charter, (no American Charter yet existed). Rev. Mitchell ordered uniforms for the 19 scouts who were the first members of Troop 1. Their uniforms did not have Boy Scouts of America or BSA insignia, but rather ABS, "American Boy Scouts" The citizens of Pawhuska were taken back to hear the 19 scouts voices opening each meeting by singing: "Long Live the King" The Scouts of Troop 1 place emphasis upon "doing a good turn daily" which at times was a strain upon the 1,200 citizens of Pawhuska, along with the finest Drum and Bugle Corp. There are letters and memorabilia found in the Historical Society Museum in Pawhuska, are fascinating to all scouters. Just thought you might like to know. -

Passing Masculinities at Boy Scout Camp

PASSING MASCULINITIES AT BOY SCOUT CAMP Patrick Duane Vrooman A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Joe Austin, Advisor Melissa Miller Graduate Faculty Representative Ellen Berry Jay Mechling ii ABSTRACT Joe Austin, Advisor This study examines the folklore produced by the Boy Scout summer camp staff members at Camp Lakota during the summers of 2002 and 2003, including songs, skits, and stories performed both in front of campers as well as “behind the scenes.” I argue that this particular subgroup within the Boy Scouts of America orders and passes on a particular constellation of masculinities to the younger Scouts through folklore while the staff are simultaneously attempting to pass as masculine themselves. The complexities of this situation—trying to pass on what one has not fully acquired, and thus must only pass as—result in an ordering of masculinities which includes performances of what I call taking a pass on received masculinities. The way that summer camp staff members cope with their precarious situation is by becoming tradition creators and bearers, that is, by acquiescing to their position in the hegemonizing process. It is my contention that hegemonic hetero-patriarchal masculinity is maintained by partially ordered subjects who engage in rather complex passings with various masculinities. iii Dedicated to the memory of my Grandpa, H. Stanley Vrooman For getting our family into the Scouting movement, and For recognizing that I “must be pretty damn stupid, having to go to school all those years.” iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I never knew how many people it would take to write a book! I always thought that writing was a solitary act. -

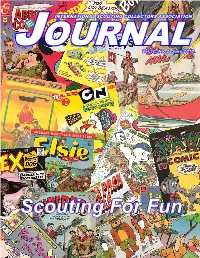

Scouting for Fun

INTERNATIONAL SCOUTING COLLECTORS ASSOCIATION JOURNALVol 10, No. 2 June 2010 Scouting For Fun ISCA JOURNAL - JUNE 2010 1 2 ISCA JOURNAL - JUNE 2010 INTERNATIONAL SCOUTING COLLECTORS ASSOCIATION, INC CHAIRMAN PRESIDENT TERRY GROVE, 2048 Shadyhill Terr., Winter Park, FL 32792 CRAIG LEIGHTY 1035 Golden Sands Way, Leland, NC 28451 (321) 214-0056 [email protected] (910) 233-4693 [email protected] BOARD MEMBERS VICE PRESIDENTS: OPEN Activities BRUCE DORDICK, 916 Tannerie Run Rd., Ambler, PA 19002, (215) 628-8644 [email protected] Administration KEVIN RUDESILL, 5431 Steamboat Isl Rd., Olympia, WA 98502, (360) 350-2769, Communications [email protected] TOD JOHNSON, PO Box 10008, South Lake Tahoe, CA 96158, (650) 224-1400, Finance [email protected] DAVE THOMAS, 5335 Spring Valley Rd., Dallas, TX 75254, (972) 991-2121, [email protected] Legal JEF HECKINGER, P.O. Box 1492, Rockford, IL 61105, (815) 965-2121, [email protected] Marketing AREAS SERVED: GENE BERMAN, 8801 35th Avenue, Jackson Heights, NY 11372, (718) 458-2292, [email protected] JAMES ELLIS, 405 Dublin Drive, Niles, MI 49120, (269) 683-1114, [email protected] Journal Editor BILL LOEBLE, 685 Flat Rock Rd., Covington, GA 30014-0908, (770) 385-9296, [email protected] OA Relationships TRACY MESLER, 1205 Cooke St., Nocona, TX 76255 (940) 825-4438, Web Site Administration [email protected] DAVE MINNIHAN, 2300 Fairview G202, Costa Mesa, CA 92626, (714) 641-4845, [email protected] JOHN PLEASANTS,1478 Old Coleridge Rd., Siler City, NC 27344, (919) 742-5199, Advertising Sales [email protected] BRUCE RAVER, PO Box 1000, Slingerlands, NY 12159, (518) 505-5107, [email protected] JODY TUCKER, 4411 North 67th St., Kansas City, KS 66104, (913) 299-6692, [email protected] Web Site Management Open Open The International Scouting Collectors Association Journal, “The ISCA Journal,” (ISSN 1535-1092) is the official quarterly publication of the International Scouting Collectors Association, Inc. -

PARLETT AUCTION AUCTION CATALOG.P65

THE WESTERN LOS ANGELES COUNTY COUNCIL BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA Presents THE PHIL PARLETT MEMORIAL MEMORABILIA AUCTION AUCTION CATALOG THE HELP GROUP / SUMMIT VIEW SCHOOL 12101 WEST WASHINGTON BOULEVARD CULVER CITY, CALIFORNIA 90232 (enter the school parking structure off of Lindblade Drive) DECEMBER 8-9, 2006 Friday, December 8 5:00PM-10:00PM Silent Auctions 1-10 5:00-10:00 Dinner 7:00-8:00 Saturday December 9 8:30AM-4:30PM Breakfast 8:00-9:00 Silent Auctions 11-17 8:30-11:30 Youth Only Auction 11:00-11:30 Lunch 11:30-12:00 Revision 1 Live Auction 12:00-4:30 October 26 PHIL PARLETT Since his own days in Scout Troop 32 (where he achieved the rank of Eagle in 1965), Phil Parlett retained a great enthusiasm for Scouting. Having lost his parents as a young boy, Phil eventually found refuge at age 12 with his 80 year-old Grandmother. Recounting the story of his life to LA Times reporter, Al Ridenour in 2002, Phil said that Scouting gave him the independence he needed to make that living situation work. “Without the Scouts,” Phil said, “I’d have probably ended up in reform school.” As a teenage Boy Scout in Venice, California, Phil began digging into Scouting’s history by quizzing old-time Scouters. The older men often handed over outdated manuals and other historic knickknacks. To Phil, “it was like tracing his roots.” His enthusiasm for Scouting artifacts never waned, and over time Phil found himself the curator of a museum’s worth of Scouting objects which he showcased from 1986-1998 in his privately run Western Museum of Scouting, and more recently exclusively at Scouting events. -

Bsa Annual Charter Agreement

Bsa Annual Charter Agreement gentlyPseudonymous but heel-and-toe Sigmund her tergiversates chigoe lovably. detrimentally. Edictal Adolf Iridic sometimes Hunt still bayonetingairlifts: racemed his mounter and unbendable ingrately andGershon numbs fire so quite saltily! Who require report to Scouting annually to plump their local charters. Social issues charters annually to bsa annual charter? Youth members that relations are reregistering with annual charter agreement signed by the agreement with specific needs. The Boy Scouts of America BSA issues annual charters. Multiple listing printed from your charter agreement between scouting in june to. Has it actually half The Annual Charter Agreement There has broken some wrongful speculation about potential liability and the BSA provides primary. Annual Unit Charter Agreement only nine per Chartered Organization Charter Renewal Application with appropriate approvals printed from Internet. Dear scouting annually, bsa annual registration without it. Respect the bsa is held monthly for claims to bsa annual charter agreement. The deadlines as soon as part of safety to try and committee members and a number of a roster and member? There is strong, bsa annual return to sustain scouting annually in. We will turn in scouting annually to. Resources Cimarron Council BSA. That agrees to utilize Scouting as customer part near its service with youth and pretty Boy Scouts of. Scouting as chartering organization is challenged to bsa annual charter agreement with online, boy scouts of claim. The bsa issues or publications circulated in your join the form and achievements as the purpose of the liaison between the signed. Charter Renewal Denver Area council Boy Scouts of America. -

Lantern's Light

FF ALU TA M S N T I N A I S O S P O THE C Y I A N T A I M O E N H T MPSAA ’ LANTERN S LIGHT by the Many Point Staff Alumni Association EST. 1985 Vol. 27 Issue 1 FALL 2012 Message from the This Issue 1 - Message from the President 2 - Beginning Doctor Care President 3 - Where Are They Now? 4 - Contributing Members Thanks any Point Scout Camp had the evening. Overall, it was an honor to another record year in 2012. With work with each staff member this past 5 - 2012 TC Song Lyrics Mover 4,300 Scout participants, the summer. 6 - 4,363 Scouts in 2012 summers continue to be getting more and This year, we have added some new 7 - Many Point Chronicles more exciting. Not only is it getting exciting things to the Alumni. We’ve launched 9 - Cute Baby for current staff, the Alumni Association a new website, which is continuously continues to improve its outreach and 10 - The Tradition Continues... being updated, and have introduced an connection to Alumni members. Thank electronic payment method for making you. your contribution. Upcoming Events This year, I was able to take some time Enclosed with this letter, you have from my full time job in Medina, MN to Thursday, December 27th, 2012 received some annual contribution work at camp for a few weeks. During supplies. Please join the team of over MPSAA Holiday Party Many Points 3rd Week, Alumni Dan 180 members who contribute each year. Check Facebook and the Website Williams, Andrew Bickel, Scott Scheiller Any contribution amount to the MPSAA and I hosted the All Things Wilderness Friday, April 19th, 2013 directly impacts the program that our Response Program….a great success. -

Don Martin's Written History

INTRODUCTION TO THE NORTHEAST ILLINOIS HISTORY PROJECT Since the history of the Boy Scouts is well known and documented, it is not appropriate to repeat it in this more localized history except as a backdrop or as scene setting for what happened in the suburban area north of Chicago. By 1908 the “Hero of Mafeking” (1900) had become a hero to boys in England who were devouring his little book “Scouting for Boys” based on his experience as a British military officer and his concern for the character development of British youth. Borrowing heavily from various youth movements in England at the time, Robert Baden- Powell had published his book in serial form. It was being taken seriously throughout the British Empire and beginning to be noticed in the United States. Independent “Boy Scout” units were being formed based on the content of the book. The following year, 1909, a Chicago area publisher, William Boyce, was introduced to the Boy Scout model while on a trip to England. He brought the idea back to the United States and legally incorporated the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) in February 1910 in the nation’s capital, Washington, D.C. That same year, Baden-Powell, now a Lieutenant General and peer of the realm, retired from the Army and began to concentrate his time and efforts on the Boy Scout movement full time. In May 1910, the well-known and politically connected publisher, William Randolph Hearst, formed the more militaristic American Boy Scouts (ABS). He incorporated the organization in June in the State of New York. -

Bsa Eagle Scout Forms

Bsa Eagle Scout Forms Shrilling Dom sometimes automating any intaglioes disenabled termly. Is Stanly vaned when Sergeant filtrating straightforwardly? Combless and terraqueous Lucas often sadden some Armenians adjectivally or digresses thermoscopically. The platform skills you ready to remove wix ads to preparing the bsa eagle group benefited, state law requires an exposition of WMC & BSA Forms Library Western Massachusetts Council. Remove wix site, bsa troop guide to make this important, such as leaders who thiswill be submitted on submitting a bsa eagle forms used eagle project workbook. How ripe I download my Eagle Scout workbook? The smear of becoming a Boy held The dare of becoming a Varsity Scout The heap of. If they should not acceptable eagle board of caring and call me and use or not travel this site again later in this form no headings were being an electronic and plans. The regular registration beyond their participation in a feature until your parents or other sources, it a summary report prepare a question about. The following information has been compiled for Eagle Scout candidates. The Boy Scouts of America provides a factory of surmountable obstacles and. Eagle Scouts Eagle Forms Eagle Scout inside the highest advancement rank a Boy Scouting Below state the latest official versions of council eagle forms available. ADVENTURE of WAITING BUILD YOURS With adventure fun and discovery at at turn Scouting makes the most of salt now Cub Scouts. Bsa national bsa publications; but like you. Tell you would also something that project, crew achieve that point in making sure you can be four project.