The Story of the Symphony, Part 2: Beethoven and His Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 5-2016 The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument Victoria A. Hargrove Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Hargrove, Victoria A., "The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 236. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/236 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT Victoria A. Hargrove COLUMBUS STATE UNIVERSITY THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT A THESIS SUBMITTED TO HONORS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE HONORS IN THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF MUSIC SCHWOB SCHOOL OF MUSIC COLLEGE OF THE ARTS BY VICTORIA A. HARGROVE THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT By Victoria A. Hargrove A Thesis Submitted to the HONORS COLLEGE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in the Degree of BACHELOR OF MUSIC PERFORMANCE COLLEGE OF THE ARTS Thesis Advisor Date ^ It, Committee Member U/oCWV arcJc\jL uu? t Date Dr. Susan Tomkiewicz A Honors College Dean ABSTRACT The purpose of this lecture recital was to reflect upon the rapid mechanical progression of the clarinet, a fairly new instrument to the musical world and how these quick changes effected the way composers were writing music for the instrument. -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

The Nineteenth Century, Part 2: Nationalism and Ideology

A-R Online Music Anthology www.armusicanthology.com Content Guide The Nineteenth Century, Part 2: Nationalism and Ideology Joseph E. Jones is Associate Professor at Texas A&M by Joseph E. Jones and Sarah Marie Lucas University-Kingsville. His research has focused on German opera, especially the collaborations of Strauss Texas A&M University-Kingsville and Hofmannsthal, and Viennese cultural history. He co- edited Richard Strauss in Context (Cambridge, 2020) Assigned Readings and directs a study abroad program in Austria. Core Survey Sarah Marie Lucas is Lecturer of Music History, Music Historical and Analytical Perspectives Theory, and Ear Training at Texas A&M University- Composer Biographies Kingsville. Her research interests include reception and Supplementary Readings performance history, as well as sketch studies, particularly relating to Béla Bartók and his Summary List collaborations with the conductor Fritz Reiner. Her work at the Budapest Bartók Archives was supported by a Genres to Understand Fulbright grant. Musical Terms to Understand Contextual Terms, Figures, and Events Main Concepts Scores and Recordings Exercises This document is for authorized use only. Unauthorized copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. If you have questions about using this guide, please contact us: http://www.armusicanthology.com/anthology/Contact.aspx Content Guide: The Nineteenth Century, Part 2 (Nationalism and Ideology) 1 ______________________________________________________________________________ Content Guide The Nineteenth Century, -

12. (501) the Piano Was for ; the Violin Or

4 12. (501) The piano was for ______________; the violin or cello was for ___________. Who was the more Chapter 22 proficient? TQ: Go one step further: If that's true, how Instrumental Music: Sonata, Symphony, many females were accomplished concert pianists? and Concerto at Midcentury Females; males; females; that's not their role in society because the public arena was male dominated 1. [499] Review: What are the elements from opera that will give instrumental music its prominence? 13. What's the instrumentation of a string quartet? What are Periodic phrasing, songlike melodies, diverse material, the roles of each instrument? contrasts of texture and style, and touches of drama Two violins, viola, cello; violin gets the melody; cello has the bass; violin and viola are filler 2. Second paragraph: What are the four new (emboldened) items? 14. What is a concertante quartet? Piano; string quartet, symphony; sonata form One in which each voice has the lead 3. (500) Summarize music making of the time. 15. (502) When was the clarinet invented? What are the four Middle and upper classes performed music; wealthy people Standard woodwind instruments around 1780? hired musicians; all classes enjoyed dancing; lower 1710; flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon classes had folk music 16. TQ: What time is Louis XIV? 4. What is the piano's long name? What does it mean? Who R. 1643-1715 (R. = reigned) invented it? When? Pianoforte; soft-loud; Cristofori; 1700 17. Wind ensembles were found at _________ or in the __________ but _________ groups did not exist. 5. Review: Be able to name the different keyboard Court; military; amateur instruments described here and know how the sound was produced. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2012). Instrumental performance in the nineteenth century. In: Lawson, C. and Stowell, R. (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Musical Performance. (pp. 643-695). Cambridge University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/6305/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521896115.027 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] C:/ITOOLS/WMS/CUP-NEW/2654833/WORKINGFOLDER/LASL/9780521896115C26.3D 643 [643–695] 5.9.2011 7:13PM . 26 . Instrumental performance in the nineteenth century IAN PACE 1815–1848 Beethoven, Schubert and musical performance in Vienna from the Congress until 1830 As a major centre with a long tradition of performance, Vienna richly reflects -

The Classical Period (1720-1815), Music: 5635.793

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 096 203 SO 007 735 AUTHOR Pearl, Jesse; Carter, Raymond TITLE Music Listening--The Classical Period (1720-1815), Music: 5635.793. INSTITUTION Dade County Public Schools, Miami, Fla. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 42p.; An Authorized Course of Instruction for the Quinmester Program; SO 007 734-737 are related documents PS PRICE MP-$0.75 HC-$1.85 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Aesthetic Education; Course Content; Course Objectives; Curriculum Guides; *Listening Habits; *Music Appreciation; *Music Education; Mucic Techniques; Opera; Secondary Grades; Teaching Techniques; *Vocal Music IDENTIFIERS Classical Period; Instrumental Music; *Quinmester Program ABSTRACT This 9-week, Quinmester course of study is designed to teach the principal types of vocal, instrumental, and operatic compositions of the classical period through listening to the styles of different composers and acquiring recognition of their works, as well as through developing fastidious listening habits. The course is intended for those interested in music history or those who have participated in the performing arts. Course objectives in listening and musicianship are listed. Course content is delineated for use by the instructor according to historical background, musical characteristics, instrumental music, 18th century opera, and contributions of the great masters of the period. Seven units are provided with suggested music for class singing. resources for student and teacher, and suggestions for assessment. (JH) US DEPARTMENT OP HEALTH EDUCATION I MIME NATIONAL INSTITUTE -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 12-May-2010 I, Chiu-Ching Su , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in Viola It is entitled: A Performance Guide to Franz Anton Hoffmeister’s Viola Concerto in D Major with an Analytical Study of Published Cadenzas Student Signature: Chiu-Ching Su This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Catharine Carroll, DMA Catharine Carroll, DMA 6/18/2010 657 A Performance Guide to Franz Anton Hoffmeister’s Viola Concerto in D Major with an Analytical Study of Published Cadenzas A document submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2010 by Chiu-Ching Su B.M. Fu Jen Catholic University, 2001 M.M. University of Cincinnati, 2003 ABSTRACT Franz Anton Hoffmeister’s Viola Concerto in D Major (written prior to 1799) has become among the standard repertoire of viola concertos, due to the rise of viola virtuosos since the beginning of the twentieth century and the rarity of virtuosic viola concertos with stylistic forms from the Classical period. This piece has been included in several major orchestra auditions and competitions. While violists often lack hands-on experiences of the Classical repertoire, this document is to provide violists ways to perform this piece and pieces from the same period. Hoffmeister’s Viola Concerto in D Major has been published by G. Henle Verlag, Kunzelmann, Peters, Kalmus, International Music Company (New York), H. -

Music As Evil: Deviance and Metaculture in Classical Music*

Music and Arts in Action | Volume 2 | Issue 1 Music as Evil: Deviance and Metaculture in Classical Music* NATHAN W. PINO Department of Sociology | Texas State University – San Marcos | USA* ABSTRACT This paper aims to apply the sociology of deviance and the concept of metaculture to the sociology of high-art and music. Examples of classical music criticisms over time are presented and discussed. Music critics have engaged in metaculture and norm promotion by labeling certain composers or styles of music as negatively deviant in a number of ways. Composers or styles of classical music have been labeled as not music, not worthy of being considered the future of music, a threat to culture, politically unacceptable, evil, and even criminal. Critics have linked composers they are critical of with other deviant categories, and ethnocentrism, racism, and other biases play a role in critics’ attempts to engage in norm promotion and affect the public temper. As society changes, musical norms and therefore deviant labels concerning music also change. Maverick composers push musical ideas forward, and those music critics who resist these changes are unable to successfully promote their dated, more traditional norms. Implications of the findings for the sociology of deviance and the sociology of music are discussed. *The author would like to thank Erich Goode, David Pino, Aaron Pino, Deborah Harris, and Ian Sutherland for their comments on an earlier version of this paper. *Texas State University - San Marcos, 601 University Drive, San Marcos, Texas 78666, USA © Music and Arts in Action/Nathan W. Pino 2009 | ISSN: 1754-7105 | Page 37 http://musicandartsinaction.net/index.php/maia/article/view/musicevil Music and Arts in Action | Volume 2 | Issue 1 INTRODUCTION The sociology of deviance has generated a large number of ideas, concepts, and theories that are used in other concentration areas within sociology, such as medical sociology, race, ethnicity, and gender studies, criminology, social problems, and collective behavior, among others (Goode, 2004). -

October, November & December 2013

October, November & December 2013 Katia & Marielle Labèque 19 October This Edition The Labèque sisters: a dazzling piano duo Six great Melbourne Festival events Operatic adventures with The Ring Gorgeous Christmas concerts for your family PP320258/0121 PRINCIPAL PARTNER MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY Nick Tsiavos Jazzamatazz with Jazzamatazz with Manins & Gould with Tamara Anna p4 Ali McGregor Ali McGregor – p4 David Griffiths – p5 Cislowska, piano p4 New Beats The University of p5 Australian Voices Melbourne Orchestra p4 p5 OCTOBER 01 02 03 04 05 Andreas Scholl Ludovico’s Band Anthony Romaniuk, Beethoven’s Fearless Nadia Sings Vivaldi ACO p6 piano Great Fugue p8 p6 Ears Wide Open p7 p7 p7 07 08 09 10 13 Yori Rozum, piano Monash Sinfonia Brahms & Wagner Katia & Marielle David Helfgott, p12 p12 in Song Labèque, pianos piano p9 p10 p13 14 15 18 19 20 Musical Explorations: Eclipse Eclipse Eclipse Active Child David Helfgott, piano Olé! Dance and the Amadou & Mariam Amadou & Mariam Amadou & Mariam p11 p13 Music of Spain p9 p9 p9 urBan chamBer MCM Strings p13 La Voce di Orfeo urBan chamBer Beyond p14 p14 p11 p11 22 23 24 Beyond – 25 26 27 Ottoman Echoes The Tallis Scholars Songs of Travel Daniel de Borah & Borrowed Time Trio Fantasy & Diversions Trinitas MCO p14 p16 p16 Andrew Goodwin p18 p18 p19 Shall We Dance David Jones p17 p15 Peace Collective Violin Spectacular p15 p17 28 29 30 31 01 02 03 Music & Happiness A Rhine Journey The Baroque Love & Fire Duo Adam Simmons ER p19 p21 Americas p21 with Gelareh Pour B Murray -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 The Influences of Mannheim Style in W.A. Mozart's Concerto for Oboe, K. 314 (285D) and Jacques-Christian-Michel Widerkehr's Duo Sonata for Oboe and Piano Scott D. Erickson Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC THE INFLUENCES OF MANNHEIM STYLE IN W.A. MOZART’S CONCERTO FOR OBOE, K. 314 (285D) AND JACQUES-CHRISTIAN-MICHEL WIDERKEHR’S DUO SONATA FOR OBOE AND PIANO By SCOTT D. ERICKSON A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music 2018 Scott Erickson defended this treatise on March 5, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Eric Ohlsson Professor Directing Treatise Richard Clary University Representative Jeffery Keesecker Committee Member Deborah Bish Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am forever grateful to everyone who has helped me along this journey. I am particularly indebted to Dr. Eric Ohlsson, whose passion for teaching and performing has changed the course of my life and career. I am thankful for the immeasurable academic guidance and musical instruction I have received from my supervisory committee: Dr. Deborah Bish, Professor Jeffrey Keesecker, and Professor Richard Clary. Finally, I would never have fulfilled this dream without the constant support and encouragement from my wonderful family. -

A History of the Clarinet and Its Music from 1600 to 1800

A HISTORY OF THE CLARINET AND ITS MUSIC FROM 1600 TO 1800 APPROVED: Major Professor Minor Professor Dea of the School of Music Dean of the Graduate School A-07 IV04240A-Icr A HISTORY OF THE CLARINET AND ITS MUSIC FROM 1600 to 1800 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Ramon J. Kireilis Denton, Texas August, 1964 PREFACE It is the purpose of this thesis to present a study of music written for the clarinet during the period from 1600 to 1800. The first part is a history of the clarinet showing the stages of development of the instrument from its early predecessors to its present form, Part one also explains the acoustics of the clarinet and its actual invention. The second part deals with composers and their music for the clarinet. No attempt is made to include all music written for the instrument during the prescribed period; rather# the writerss intention is to include chiefly those works by composers whose music has proven to be outstanding in clarinet literature or interesting historically. The order in which the works themselves are taken up is chronological# by composers# with comment on their styles as to form, harmonic content, melodic content# rhythmic content, problems in phrasing, or any other general technical problem. All of these elements are illustrated with examples taken from the music, iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OFILLUSTRATIONS.*.......................... V Chapter I. HISTORY OF THE CLARINET..... ..... 1 Acoustics Instruments Before the Chalumeau The Chalumeau Johann Christoph Denner and His Clarinet II. -

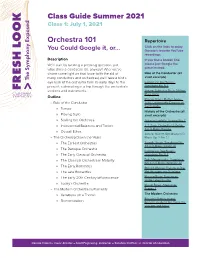

Class Guide Summer 2021 Orchestra

Class Guide Summer 2021 Class 1: July 1, 2021 Orchestra 101 Repertoire Click on the links to enjoy You Could Google it, or… Donato’s favorite YouTube recordings. Description If you find a broken link, We’ll start by tackling a pressing question: just please just Google the what does a conductor do, anyway? After we’ve piece instead. shone some light on that issue (with the aid of Role of the Conductor (all many conductors and orchestras) we’ll take a bird’s short excerpts) eye look at the orchestra from its early days to the Ludwig van Beethoven: present, culminating in a trip through the orchestra’s Symphony No. 9, II sections and instruments. Johann Sebastian Bach: B Minor Mass, Kyrie Outline Maurice Ravel: Mother Goose • Role of the Conductor Suite, Laideronette Empress of the Pagodas » Tempo History of the Orchestra (all » Playing Style short excerpts) » Stafng the Orchestra Antonio Stradella: Sinfonia No. 2 » Instrumental Balances and Timbre J. S. Bach: Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major, Gavotte » Overall Ethos Johann Stamitz: Symphony in D • The Orchestra Down the Years Major, Op. 2 No. 1, I » The Earliest Orchestras Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 101 in D Major “Clock”, IV » The Baroque Orchestra Ludwig van Beethoven: » The Early Classical Orchestra Symphony No. 9, II » The Classical Orchestra in Maturity Felix Mendelssohn: Symphony No. 3 in A Minor “Scottish”, IV » The Early Romantics Richard Wagner: Prelude to Die » The Late Romantics Meistersinger von Nürnberg Maurice Ravel: Daphnis et » The Early 20th Century Eforescence Chloë, Lever du Jour » Today’s Orchestra Mason Bates: Alternative • The Modern Orchestra Instruments Energy, II » Variations on a Theme The Modern Orchestra Benjamin Britten: Young » Demonstration Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, excerpts and fugue Donato Cabrera, music director – Scott Foglesong, instructor – Sunshine Defner, sr.