Lake Management Plan (2013)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Algonquins of Ontario

Algonquins of Ontario Friday, October 11, 2019 Changes to the 2019 – 2020 Algonquin Park Harvest Area Pembroke, ON – For many years, the annual Algonquins of Ontario harvest of moose, deer and elk has been managed pursuant to management plans developed by the Algonquin Negotiation Representatives (ANRs). These management plans establish the process of issuing tags to eligible Algonquin harvesters, the species that can be harvested, the season during which harvesting shall occur and the Harvest Area within which harvesting may take place. They also provide for reporting and monitoring of harvesting activities. These management plans have resulted in responsible and well-managed Algonquin harvesting for many years. In the past, Algonquin harvesting of moose and deer as well as the harvesting of other species of game normally taken for food in Algonquin Park has been restricted to the area within Wildlife Management Unit (WMU) 51 and to the east of Shirley Lake Road. For the 2019-2020 harvest season, the Algonquins of Ontario have decided that this area is now expanded to include that portion of Algonquin Park that lies within WMU 51, both east and west of Shirley Lake Road, north of the Hwy 60 Corridor Development Zone and within the Algonquin of Ontario Settlement Area. This decision has been taken after a great deal of consideration and is the result of anticipated increased harvesting by members of the Métis Nation of Ontario pursuant to arrangements made with the government of Ontario that have been challenged in court by the Algonquins of Ontario. In recent years moose populations in certain Wildlife Management Units have declined significantly, coinciding with increased harvesting by self-identified Métis harvesters. -

Newsletterlake Kashagawigamog Organization

WINTER 2019 NEWSLETTERLake Kashagawigamog Organization THE BEAUTY OF WINTER ON KASHAGAWIGAMOG! Lake Kashagawigamog Organization LAKE KASHAGAWIGAMOG ORGANIZATION NEWSLETTER LAKE KASHAGAWIGAMOG ORGANIZATION NEWSLETTER Greetings From The President LKO Annual SEPTIC Winter 2019 INSPECTIONS As autumn fades and winter arrives it is time to reflect on the FOCA, and local politicians to handle General summer of 2019 on Lake Kashagawigamog. The ice finally the many issues relating to the lake. receded at the beginning of May and after a wet spring we We need your help! First, we need you to Meeting The preservation of our natural environment is headed into a drought which meant sunny weekends through speak to your friends and neighbours on most of the summer. Good planning and water management an endeavour that we all share. To this end it the lake to get them to become members of the LKO. Together we will be the small individual efforts that will resulted in us having above average water levels for the season. have a more powerful voice to get things done. SATURDAY JUNE 27, 2020 make the difference, natural shorelines and The LKO had a busy summer. We started with a very successful Second, we need volunteers. They say that many hands make responsible management of our onsite Love your Lake Seminar, our Annual General Meeting, a Cottage 9:00 A.M. light work. Well, we have light work but we need more hands to wastewater. The little steps can pay big Succession Planning seminar with Soyers Lake and FOCA (www. get it done. We want to continue to put on educational and fun Location: To Be Determined foca.on.ca), and another successful Kash Bash. -

EXPLORE OUR LAKES Municipality of Dysart Et Al the Power of Lakes

EXPLORE OUR LAKES Municipality of Dysart et al The Power of Lakes RECREATION INFORMATION POINTS OF INTEREST ROUTES MAPS RENTALS TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents.............................................................Page No. Objectives............................................................................................................1 Municipal Boat Launch Map...........................................................................2 Head Lake............................................................................................................3 Cranberry Lake...................................................................................................5 Drag Lake.............................................................................................................7 Wenona Lake......................................................................................................8 Mikwabi Lake.....................................................................................................9 Farquhar Lake..................................................................................................10 Elephant Lake...................................................................................................11 Fishtail Lake......................................................................................................12 Percy Lake.........................................................................................................13 Haliburton Lake...............................................................................................14 -

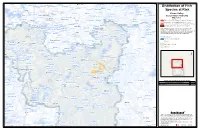

AOO Settlement Area Harvest

Wicksteed Lake Lac du Goéland 40 LA SALLE WYSE Lac Smith Marten Lake MCAUSLAN North Spruce Lake Lac du Pin Blanc Poplar LakeHAMMELL GARROWCLARKSON Lac Ramé Lac Bruce Lac Sept Milles Bear Lake OSBORNE POITRAS Lac des Cornes Tilden Lake Map A Lac– Vaucour AOO Settlement Area Harvest Map Lac Saint-Paul Lac des Sables LOCKHART Lac Curières LYMAN NOTMANSTEWART JOCKO EDDY Lac Mosquic Tomiko Lake Lac Nilgaut Lac Barton MERRICK Lac Marin Lac Caugnawana CHARLTONBLYTH Lac Royal Lac des Mocassins MULOCKFRENCHBUTLERANTOINE Lac Maganasipi 41 Lac la Cave Lac Brodtkorb Lac en Croix Lac Gauvin Lac Forbes BEAUCAGE 41 Lac Lamb COMMANDA Lac Resolin Lac Quinn WIDDIFIELD PHELPS Legend OLRIG Lac Murray HWY 17 MATTAWAN Lac à la Tortue Lac McCracken Trout Lake Mattawa Lac Saint-Patrice Lake Talon (lac Talon) Algonquins of Ontario Settlement Area Boundary 42 HWY 17 Lac Dodd Lake Nipissing (lac Nipissing) Rutherglen Lac Duval Lac Wright BONFIELD Lac Schyan FERRIS CALVIN PAPINEAU Deux-Rivières Grand lac des Cèdres Lake Nosbonsing (lac Nosbonsing) Holden Lake Algonquin Park HarvestLac Area Montjoie Stonecliffe Lac Désert Astorville CAMERON CLARA Lac de la Mer Bleue LAUDER Lac Blue Sea Lac Chapleau Wasi Lake (lac Wasi) Rolphton NIPISSING 48 MARIA Harvest Area for Elk BOULTER HEAD CHISHOLM Kiosk BOYD Restoule Lake Lac Galarneau Kioshkokwi Lake ROLPH Deep River Lac Cayamant Lac Marie-Le Franc Commanda Lake PENTLAND FITZGERALD Lac Jim Wildlife Management Unit (WMU) WILKES DEACON Mountain View HIMSWORTH Manitou Lake Carl Wilson Lake Lac McGillivray 47 Cedar Lake BRONSON -

Waterfront Owners Not Loving Their Lakes

Cottage Your lot Your dream IMAGINE Country Custom built THE PLACES Building YOU’LL GO... Supplies 13523 HWY #118 WEST, HALIBURTON 15492 Highway #35. | Carnarvon | Ontario 11576 Hwy 35 • www.RoyalHomesMinden.on.ca 7054579355 705-489-2212 | [email protected] 705-286-6992 1-888-717-4923 www.highlandsmedicalsupplies.com HOME OF THE HIGHLAND STORM TheHighlanderThursday July 5 2018 | Issue 346 INSIDE: NEW HIGHLANDER WEEKEND SECTION FREE The heat is on... KIds jump into the water in Head Lake Park to keep cool during the heat wave. Photo by Mark Arike Waterfront owners not loving their lakes By Mark Arike according to a scientific review by the 13,487 properties on 72 lakes (60 are in the phosphorus from septic systems is the Muskoka Watershed Council. county). This includes information on four leading cause of its growth. In some places, The latest findings of the Love Your Lake “Only five made the grade,” CHA chair natural shoreline classifications: natural, blooms have led to swimming bans and a program are similar to last year. Paul MacInnes told county council on June regenerative, ornamental and degraded. It drop in property values. Of the 60 local lakes surveyed by the 27. also took into account setbacks and dock “The Canadian Real Estate Association Coalition of Haliburton Property Owners’ A total of 5,228 properties, or 939 km of types. has come out with a statistic that one blue- Association (CHA), only eight per cent had shoreline, need to be re-naturalized, said The CHA obtained more than $300,000 in green algae bloom on a lake will drive adequate natural shorelines. -

In the Highlands with Colin + Justin Home May 2020 Your Guide to Cottage Country

IN THE HIGHLANDS WITH COLIN + JUSTIN HOME MAY 2020 YOUR GUIDE TO COTTAGE COUNTRY CONTACT US TODAY FOR JEFF & ANDREA* STRANO • MARJ & JOHN PARISH A FREE PROPERTY EVALUATION SALES REPRESENTATIVES/*BROKER PARISHANDSTRANO.CA RE/MAX Professionals North, Brokerage Independently Owned & Operated. KAWARTHA LAKES • HALIBURTON • PETERBOROUGH 2/HOME IN THE HIGHLANDS KAWARTHAKAWARTHA LAKES LAKES • HALIBURTON • HALIBURTON • PETERBOROUGH• PETERBOROUGH KAWKARTHAAWKARTHAAW ARTHALAKES LAKES • LAKES HALIBURTON • HALIBURTON • HALIBURTON • PETERBOROUGH • PETERBOROUGH • PETERBOROUGH KAWARTHA LAKES • HALIBURTON • PETERBOROUGH WINDOWS & DOORS SUNROOMS PORCH ENCLOSURES CLOSED WINDOWS & DOORS SUNROOMS PORCHOPEN ENCLOSURES WINDOWSWINDOWSWINDOWS & DOORS & DOORS & DOORS SUNROOMSSUNROOMSSUNROOMS PORCH PORCH ENCLOSURES PORCH ENCLOSURES ENCLOSURES WINDOWS & DOORS SUNROOMS PORCH ENCLOSURES CLOSED WINDOWS & DOORS SUNROOMS PORCHOPEN ENCLOSURES CLOSEDCLOSEDCLOSED OPEN OPENOPEN CLOSED OPEN CLOSED OPEN INCREASED ENERGY PROTECTION 3- AND 4- WHEN OPEN: WHEN CLOSED: LIFESPAN EFFICIENT FROM BUGS SEASON MODULAR 75% RAIN & BUG & RAIN OPTIONS VENTILATION PROTECTION INCREASED ENERGY PROTECTION 3- AND 4- WHEN OPEN: WHEN CLOSED: LIFESPAN EFFICIENT FROM BUGS SEASON MODULAR 75% RAIN & BUG INCREASEDINCREASEDINCREASEDENERGYENERGYENERGYPROTECTIONPROTECTIONPROTECTION& RAIN3- AND3- 4- ANDOPTIONS3- 4-AND WHEN4- WHEN OPEN:VENTILATIONWHEN OPEN:WHEN OPEN:WHEN CLOSED:WHEN PROTECTIONCLOSED: CLOSED: LIFESPANLIFESPANLIFESPANEFFICIENTEFFICIENTEFFICIENTFROM FROMBUGSFROM BUGSSEASON BUGSSEASON MODULARSEASON -

Spring/Summer 2016 Newsletter

SPRING 2016 NEWSLETTERLake Kashagawigamog Organization LAKE KASHAGAWIGAMOG ORGANIZATION NEWSLETTER President’s Message Spring 2016 Welcome back to the lake and hopefully another beautiful the intent of these signs. summer like we enjoyed last year. After a very mild el Niño We continue to have many people to thank for their winter, spring has been very slow to arrive in southern Ontario contribution to the LKO. First I’d like to thank our web- but that hasn’t stopped your LKO board from continuing our master Hugh Switzer for his continued input and support ongoing programs dedicated to improving water quality and of our web site, and board member Jane Nugent for her shorelines on our lake. efforts in compiling and distributing the always informative An unfortunate fact of life is that both our AGM and our regatta e-newsletters. All of our board members play a significant are poorly attended even though a great deal of volunteer role in ensuring this organization functions smoothly. I would effort goes into the planning and execution of both events. like to especially thank Glenda Bryson for her contribution We have traditionally held our AGM on a late June weekend, to the health of our lake in her role as Lake Steward. Glenda and our regatta in mid-July. This year we are going to try has devoted untold hours in learning and implementing the something different and hold both events on the same day specific testing regimes in this ever expanding role. When at the same location. I am excited to announce that Halimar you see Glenda out on the lake please give her a big wave for Resort has agreed to host both the AGM and the regatta on all of us. -

Trent Assessment Report

TRENT CONSERVATION COALITION SOURCE PROTECTION REGION Approved Trent Assessment Report Approved October 1, 2014 Volume 1 of 3 Effective Janurary 1, 2015 Updated February 15, 2018 Trent Source Protection Areas: Crowe Valley Source Protection Area Kawartha-Haliburton Source Protection Area Lower Trent Source Protection Area Otonabee-Peterborough Source Protection Area Made possible through the support of the Government of Ontario www.trentsourceprotection.on.ca This Assessment Report was prepared on behalf of the Trent Conservation Coalition Source Protection Committee under the Clean Water Act, 2006. TRENT CONSERVATION COALITION SOURCE PROTECTION COMMITTEE Jim Hunt (Chair) Municipal The Trent Conservation Coalition Source Dave Burton Protection Committee is a locally based Rob Franklin (Bruce Craig to June 2011) committee, comprised of 28 Dave Golem representatives from municipal Rosemary Kelleher‐MacLennan government, First Nations, the Gerald McGregor commercial/industrial/agriculture sectors, Mary Smith and other interests. The Committee’s Richard Straka ultimate role is to develop a Source Protection Plan that establishes policies for Commercial/Industrial preventing, reducing, or eliminating threats Monica Berdin, Recreation/Tourism to sources of drinking water. In developing Edgar Cornish, Agriculture the plan, the committee members are Kerry Doughty, Aggregate/Mining Robert Lake, Economic Development committed to the following: Glenn Milne, Agriculture . Basing policies on the best available Bev Spencer, Agriculture science, and -

Deer Roams Haliburton with Arrow in Head Deer It Had an Arrow out the Side of Its Head

Cottage Country DARK? Call GENERATOR SOLUTIONS and 20%in store OFF only make sure the lights never go out. Building Offer valid until Wednesday January 31, 2018 Supplies Talk to us about fi nancing. FREE Delivery on in stock chairs only 13523 HWY #118 WEST, HALIBURTON 15492 Highway #35. | Carnarvon | Ontario 7054579355 705-489-2212 | [email protected] www.highlandsmedicalsupplies.com HOME OF THE HIGHLAND STORM TheHighlanderThursday January 11 2018 | Issue 321 INSIDE: YEAR IN REVIEW - PAGE 8 FREE Anti-bullying front and centre on clothing line Caitlin Dunlop does a photo shoot for the new clothing line. Photo by Lisa Gervais. See story on page 5. Deer roams Haliburton with arrow in head deer it had an arrow out the side of its head. “I thought there might me a process Resources and Forestry (MNRF) but said By Lisa Gervais Then, I noticed an arrow between its eyes to deal with injured deer as the deer are they’d continue to monitor the situation. The mysterious case of the deer with an up on the forehead. I told my husband I commonplace in town. We love them and Sparling said the OPP came to the property arrow in its head continues in Haliburton. noticed a red sore mark at the side of this I’m sure others do as well.” and took a photo of the deer but left without Marlene Sparling, who lives on Pine same deer and concluded the first arrow First, she called the local Ontario speaking to them. Street, first alerted The Highlander about had come out but someone now had shot it Provincial Police. -

Chapter 1 WHAT IS LAKE PLANNING

1 ii Preamble People residing along the shorelines of the lakes and rivers in Ontario are drawn by the quality of the water, the exposure to nature, the offer of peace and tranquility, and the attraction of sustainable recreational opportunities. What makes each shoreline unique is the particular blend of natural and human communities that thrive there. A growing number of shoreline groups are conducting studies regarding the character and qualities of their respective communities ranging from the casual to the complex. By following their lead, we can establish what it is about our lakes, shorelines, surrounding environment, and communities that should be retained and sustained for future generations. The study of our lake surroundings and shoreline communities requires “One of your most knowledge, patience, enthusiasm and persistence. We have the early powerful tools is to pioneers in lake planning to thank for paving the way for those who will write a report on follow. However, what has yet to be done is to draw upon that collective your own lake and body of experience in order to lay out the process of lake planning in a area. After all, who knows your lake and simple and easily understood manner. Whether a group is either large or area better then small, of greater or lesser means, or narrow or broadly focused, they all must you?” be able to find, within the pages of this handbook, the information they need to design and support their individual planning and stewardship efforts. …Jerry Strickland FOCA (1990) What does this handbook provide? This handbook is best described as a self-help guide. -

Distribution of Fish Species at Risk

Hound Lake McCormick Lake Chip Lake Grace Creek Round Island Ketcheson IslandShiner Lake Dog Lake Hound Creek Dry Narrows Robinson Lake Holland Lake Bowen Corner Little Mayo Lake Weddell Island High Falls Bird Lake South Boundary Lake Farm Chute Edward Lake Fosters Lake Horseshoe Bay Birds Creek MaxwellGrace Lake The Great Bend Aide Creek Egan Chute Lyman Island Jamieson Lake Green Narrows West Bay Effingham Lake Distribution of Fish Madawaska Highlands Bowen Creek Mullet Lake Mayo Lake Sleeper Lake Little Mullet Lake Egan Creek Swordfingal Lake Smith Lake Rockwells IslanLdittle Long Lake Hughes Hay Bay Dog Bay Weslemkoon Lake Species at Risk Clark Lake Clark Creek V Lake Coburn Creek Redmond Bay Brethour Lake Bronson Canoe Lake Mullet Creek Tilney Lake Trip Lake The Eagles Nest Copper Lake L'Amable Creek Buck Lake Weslemkoon Crowe Valley Aide Lake Kerr Lake Baptiste Faraday CreeBk ancroft Airfield Little Bear Pond Baudette Lake Little Sunken Lake Grassy Lake Burtchell Creek York River Little Birch Lake Conservation Authority Waterhouse Lake York River O'Neill Lake Vanluven Lake Bronson Lake Detlor Bancroft Beech Lake (Map 1 of 2) North Vance Lake The Chain Lakes McCrae Bronson Station Pond Lily Lake Beechmount Kelly Creek Venalen Lake Spruce Lake Faraday Lake Fraser Creek DiamondD Liaamkeo Dnadm Lake Marble Lake Bon Echo Creek Whitefoot Lake Nobbs Lake Jordan Lake McGibbon Lake Card Lake Lost Lake Derry Lake Spurr Lake Jimmie Lake East Tommy Lake Hudson Creek Tait Lake Todd Lakes Riddell Lake Egan Lake Currie Lake Highland Grove -

Written Submission from the Algonquins of Ontario Mémoire Des

CMD 18-M48.12 File/dossier : 6.02.04 Date : 2018-11-27 Edocs pdf : 5721870 Written submission from the Mémoire des Algonquins of Ontario Algonquins de l’Ontario In the Matter of À l’égard de Regulatory Oversight Report for Uranium Rapport de surveillance réglementaire des Mines, Mills, Historic and Decommissioned mines et usines de concentration d’uranium et Sites in Canada: 2017 des sites historiques et déclassés au Canada : 2017 Commission Meeting Réunion de la Commission December 12, 2018 Le 12 décembre 2018 Review of CNSC Regulatory Oversight Report: Uranium Mines, Mills, Historic, and Decommissioned Sites in Canada (2017) Algonquins of Ontario Contents ...........................................................................................................................................................i Contents ..........................................................................................................................................i Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 2 Core Issues and Accommodations for the AOO .......................................................... 6 Traditional Knowledge and Cultural Heritage Considerations ................................. 13 General Comments & Accommodations ................................................................... 17 Summary ........................................................................................................................... 22 6.0 References