THE FINAL WORD Issue 124 Dec

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USDA Former Secretaries USMCA Letter

September 18, 2019 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Kevin McCarthy Speaker Minority Leader U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20515 The Honorable Mitch McConnell The Honorable Chuck Schumer Majority Leader Minority Leader U.S. Senate U.S. Senate Washington, D.C. 20510 Washington, D.C. 20510 Dear Speaker Pelosi, Minority Leader McCarthy, Majority Leader McConnell and Minority Leader Schumer, As former Secretaries of Agriculture, we recognize how important agricultural trade is to the U.S. economy and rural America. We know from experience that improved market access creates significant benefits to U.S. farmers and ranchers. We believe that the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) will benefit American agriculture and related industries. With Canada and Mexico being the first and second largest export markets for U.S. agricultural products, we believe USMCA makes positive improvements to one of our most critical trade deals. Currently, NAFTA supports more than 900,000 jobs in the U.S. food and agriculture sector and has amplified agricultural exports to our North American neighbors to $40 billion this past year. Before NAFTA went into effect in 1994, we were exporting only $9 billion worth of agricultural products to Canada and Mexico. The International Trade Commission’s recent economic analysis concluded that USMCA would benefit our agriculture sector and would deliver an additional $2.2 billion in U.S. economic activity. Trade is extremely vital to the livelihood of American farmers and the U.S. food industry. U.S. farm production exceeds domestic demand by 25 percent. -

Nominations to the Department of Transportation, the Department of Commerce, and the Executive Office of the President

S. HRG. 111–418 NOMINATIONS TO THE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION, THE DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE, AND THE EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION APRIL 21, 2009 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 52–165 PDF WASHINGTON : 2010 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:04 May 18, 2010 Jkt 052165 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\WPSHR\GPO\DOCS\52165.TXT SCOM1 PsN: JACKIE SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia, Chairman DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas, Ranking JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota JOHN ENSIGN, Nevada BARBARA BOXER, California JIM DEMINT, South Carolina BILL NELSON, Florida JOHN THUNE, South Dakota MARIA CANTWELL, Washington ROGER F. WICKER, Mississippi FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia MARK PRYOR, Arkansas DAVID VITTER, Louisiana CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas AMY KLOBUCHAR, Minnesota MEL MARTINEZ, Florida TOM UDALL, New Mexico MIKE JOHANNS, Nebraska MARK WARNER, Virginia MARK BEGICH, Alaska ELLEN L. DONESKI, Chief of Staff JAMES REID, Deputy Chief of Staff BRUCE H. ANDREWS, General Counsel CHRISTINE D. KURTH, Republican Staff Director and General Counsel PAUL NAGLE, Republican Chief Counsel (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:04 May 18, 2010 Jkt 052165 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\WPSHR\GPO\DOCS\52165.TXT SCOM1 PsN: JACKIE C O N T E N T S Page Hearing held on April 21, 2009 ............................................................................. -

Accentuating the Positive in Nebraska's GOP Race for Governor

July 1, 1998 Accentuating the Positive in Nebraska's GOP Race for Governor Bob Wickers Mike Johanns was outspent by $2 million, never mentioned his opponents' names on TV - and won a big primary victory We started the campaign knowing three things: 1) We were going to be considerably outspent by both of our opponents; 2) We were going to build a grassroots organization in all 93 counties throughout Nebraska and 3) We were going to stay positive no matter what. On primary night, Tuesday, May 12th, we stood in a packed hotel ballroom in Lincoln, Nebraska. The room was overflowing with campaign workers, reporters and supporters, all waiting for the imminent arrival of Mike Johanns, whom the Associated Press had just declared the winner in the Republican primary for governor. There were cell phones ringing and reporters going live on the air, and the moment when Mike, his wife Stephanie, and children Michaela and Justin finally walked in, the crowd erupted into cheers and applause that could be heard from Omaha to Scottsbluff. We were reminded of the day when we first met Mike Johanns, more than a year earlier, when this night seemed a long way off. In the spring of 1997, we had traveled to Lincoln to meet Johanns. As the mayor of Lincoln, he had earned respect and accolades for his conservative leadership style and ability to get things done. The city had experienced unprecedented economic growth and enjoyed a AAA bond rating while seeing cuts in property taxes and an increased number of police on the streets. -

HAYWORTH: US Senate Candidate Domina Seeks

HAYWORTH: U.S. Senate candidate Domina seeks Nebraska foothold January 22, 2014 Bret Hayworth Democratic U.S. Senate candidate Dave Domina is looking for traction in a solidly Republican state. When speaking in South Sioux City at the Dakota Perk cafe Wednesday amid his campaign launch swing, Domina heard some math that could provide some solace. Dick Erickson, of Jackson, Neb., described living in low-population, conservative Rock County, where he was elected as a Democrat to the assessor position. Erickson said he won in spite of the Republican voter registration lead being about 850 to 250 over Democrats. "They were tired of the present administration and I think that is true today," he said. Erickson said that means an upstart can persevere through unfavorable political math. Domina, an attorney from Omaha, launched his campaign for the Senate seat in Nebraska on Tuesday. In moving through Northeast Nebraska, he made stops in Norfolk, Wayne and South Sioux City. Domina will speak in many more towns before his kickoff campaign swing ends Sunday. Domina told the crowd of 30 that he sees a winning recipe by doing well in the metropolitan Omaha and Lincoln areas, then nabbing votes in the conservative rural parts of the state lying primarily in the 3rd Congressional District. Domina said people wonder how he can win in 2014 if Bob Kerrey, a former U.S. senator, couldn't achieve a comeback win in 2012? (Kerrey lost to Republican Deb Fischer.) Domina said Kerrey had a negating factor in having lived away from the state for many years until returning to run in 2012. -

National Press Club Luncheon with Agriculture Secretary Mike Johanns

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON WITH AGRICULTURE SECRETARY MIKE JOHANNS SUBJECT: THE FARM BILL MODERATOR: JERRY ZREMSKI, PRESIDENT, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LOCATION: NATIONAL PRESS CLUB BALLROOM, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 1:00 P.M. EDT DATE: FRIDAY, JULY 27, 2007 (C) COPYRIGHT 2005, FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC., 1000 VERMONT AVE. NW; 5TH FLOOR; WASHINGTON, DC - 20005, USA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ANY REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED. UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES A MISAPPROPRIATION UNDER APPLICABLE UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW, AND FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC. RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PURSUE ALL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO IT IN RESPECT TO SUCH MISAPPROPRIATION. FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC. IS A PRIVATE FIRM AND IS NOT AFFILIATED WITH THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT. NO COPYRIGHT IS CLAIMED AS TO ANY PART OF THE ORIGINAL WORK PREPARED BY A UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT OFFICER OR EMPLOYEE AS PART OF THAT PERSON'S OFFICIAL DUTIES. FOR INFORMATION ON SUBSCRIBING TO FNS, PLEASE CALL JACK GRAEME AT 202-347-1400. ------------------------- MR. ZREMSKI: Good afternoon, and welcome to the National Press Club. My name is Jerry Zremski, and I'm president of the National Press Club and Washington bureau chief for the Buffalo News. I'd to welcome our club members and their guests who are here today along with those of you who are watching on C-SPAN. We are looking forward to today's speech, and afterwards, I'll ask as many questions as time permits. Please hold your applause during the speech so that we have as much time for questions as possible. For our broadcast audience, I'd like to explain that if you hear a pause during a speech, it may be from the guests and members of the general public who attend our luncheons, and not necessarily from the working press. -

Secretary Perdue Statement on USMCA Agreement

Secretary Perdue Statement on USMCA Agreement (Washington, D.C., December 10, 2019) – U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue issued the following statement after United States Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer and Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi announced agreement on the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA): “USMCA is a big win for American workers and the economy, especially for our farmers and ranchers. The agreement improves virtually every component of the old NAFTA, and the agriculture industry stands to gain significantly,” said Secretary Perdue. “President Trump and Ambassador Lighthizer are laying the foundation for a stronger farm economy through USMCA and I thank them for all their hard work and perseverance to get the agreement across the finish line. While I am very encouraged by today’s breakthrough, we must not lose sight – the House and Senate need to work diligently to pass USMCA by Christmas.” Background: USMCA will advance United States agricultural interests in two of the most important markets for American farmers, ranchers, and agribusinesses. This high- standard agreement builds upon our existing markets to expand United States food and agricultural exports and support food processing and rural jobs. Canada and Mexico are our first and second largest export markets for United States food and agricultural products, totaling more than $39.7 billion food and agricultural exports in 2018. These exports support more than 325,000 American jobs. All food and agricultural products that have zero tariffs under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) will remain at zero tariffs. Since the original NAFTA did not eliminate all tariffs on agricultural trade between the United States and Canada, the USMCA will create new market access opportunities for United States exports to Canada of dairy, poultry, and eggs, and in exchange the United States will provide new access to Canada for some dairy, peanut, and a limited amount of sugar and sugar-containing products. -

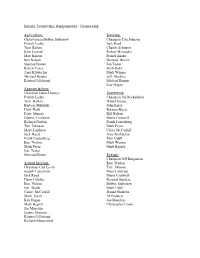

Senate Committee Assignments - Democrats

Senate Committee Assignments - Democrats: Agriculture: Banking: Chairwoman Debbie Stabenow Chairman Tim Johnson Patrick Leahy Jack Reed Tom Harkin Charles Schumer Kent Conrad Robert Menendez Max Baucus Daniel Akaka Ben Nelson Sherrod Brown Sherrod Brown Jon Tester Robert Casey Herb Kohl Amy Klobuchar Mark Warner Michael Bennet Jeff Merkley Kirsten Gillibrand Michael Bennet Kay Hagan Appropriations: Chairman Daniel Inouye Commerce: Patrick Leahy Chairman Jay Rockefeller Tom Harkin Daniel Inouye Barbara Mikulski John Kerry Herb Kohl Barbara Boxer Patty Murray Bill Nelson Dianne Feinstein Maria Cantwell Richard Durbin Frank Lautenberg Tim Johnson Mark Pryor Mary Landrieu Claire McCaskill Jack Reed Amy Klobuchar Frank Lautenberg Tom Udall Ben Nelson Mark Warner Mark Pryor Mark Begich Jon Tester Sherrod Brown Energy: Chairman Jeff Bingaman A rmed Services: Ron Wyden Chairman Carl Levin Tim Johnson Joseph Lieberman Mary Landrieu Jack Reed Maria Cantwell Daniel Akaka Bernard Sanders Ben Nelson Debbie Stabenow Jim Webb Mark Udall Claire McCaskill Jeanne Shaheen Mark Udall Al Franken Kay Hagan Joe Manchin Mark Begich Christopher Coons Joe Manchin Jeanne Shaheen Kirsten Gillibrand Richard Blumenthal Environment and Public Works: Health, Education, Labor and Pension: Chairwoman Barbara Boxer Chairman Tom Harkin Max Baucus Barbara Mikulski Thomas Carper Jeff Bingaman Frank Lautenberg Patty Murray Benjamin Cardin Bernard Sanders Bernard Sanders Robert Casey Sheldon Whitehouse Kay Hagan Tom Udall Jeff Merkley Jeff Merkley Al Franken Kirsten Gillibrand -

OCTOBER TERM 2006 Reference Index Contents

JNL06$IND1—10-16-07 16:47:01 JNLINDPGT MILES OCTOBER TERM 2006 Reference Index Contents: Page Statistics ....................................................................................... II General .......................................................................................... III Appeals ......................................................................................... III Applications ................................................................................. III Arguments ................................................................................... III Attorneys ...................................................................................... IV Briefs ............................................................................................. IV Certiorari ..................................................................................... IV Costs .............................................................................................. V Granted Cases ............................................................................. V Motions ......................................................................................... V Opinions ........................................................................................ VI Original Cases ............................................................................. VI Rehearing ..................................................................................... VI Rules ............................................................................................ -

Remarks on the Nomination of Edward T. Schafer to Be Secretary

1432 Oct. 31 / Administration of George W. Bush, 2007 at an all time high and the deficit declining, Remarks on the Nomination of now is not the time to raise taxes. Running Edward T. Schafer To Be Secretary up the taxes on the American people would of Agriculture be bad for our economy; more importantly, October 31, 2007 it would be bad for American families. I want you to have more money, so you can make The President. Thank you all. Be seated. the decisions for your families and yourself Good afternoon. I’m proud to announce my that you think are necessary. I like it when nomination of Ed Schafer to be the next Sec- the after-tax revenues—income are up. I retary of the Agriculture. think it’s good for America that American The Secretary of Agriculture heads a Cabi- families are able to save for their children’s net Department of more than 100,000 em- education or small businesses have more ployees. I rely on the Secretary to provide money to invest. And the surest way to dilute sound advice on issues ranging from our Na- that spirit of entrepreneurship is to run your tion’s farm economy and food supply to inter- taxes up. And that’s why I’m going to use national trade and conservation programs. To my veto pen to prevent people from doing carry out these responsibilities, the Secretary it. of Agriculture needs to be someone who un- You know, we’re living during challenging derstands the challenges facing America’s times. -

Blue Book, Official Manual, Secretary of State, Federal Government, Missouri

CHAPTER 3 Federal Government Edward Gill with his bicycle, 1932 Gill Photograph Collection Missouri State Archives 104 OFFICIAL MANUAL ND DIV TA ID S E D E E PLU UM RI BU N S U W W E D F E A T I L N L U www.doc.gov; SALUS X ESTO LE P O P A U L I S UP R E M M D C C C X X Robert M. Gates, Secretary of Defense; www.defencelink.mil; Margaret Spellings, Secretary of Education; United States www. ed.gov; Samuel W. Bodman, Secretary of Energy; www.energy.gov; Government Michael O. Leavitt, Secretary of Health and Hu man Services; www.hhs.gov; Michael Chertoff, Secretary of Homeland Secu- Executive Branch rity; www.dhs.gov; George W. Bush, President of the United States Alphonso Jackson, Secretary of Housing and The White House Urban Development; www.hud.gov; 1600 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W. Dirk Kempthorne, Secretary of the Interior; Washington, D.C. 20500 www.doi.gov; Telephone: (202) 456-1414 Alberto Gonzales, Attorney General; www.usdoj.gov; www.whitehouse.gov Elaine Chao, Secretary of Labor; www.dol.gov; Condoleezza Rice, Secretary of State; Note: Salary information in this section is taken from www.state.gov; “Legislative, Executive and Judicial Officials: Process for Mary E. Peters, Secretary of Transportation; Adjusting Pay and Current Salaries,” CRS Report for Con- www.dot.gov; gress, 07-13-2007. Henry M. Paulson Jr., Secretary of the Treasury; The president and the vice president of the www.ustreas.gov; United States are elected every four years by a Jim Nicholson, Secretary of Veterans Affairs; majority of votes cast in the electoral college. -

Animal Science Alumni Newsletter, Summer 2005

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Animal Science Department News Animal Science Department July 2005 Animal Science Alumni Newsletter, Summer 2005 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/animalscinews Part of the Animal Sciences Commons "Animal Science Alumni Newsletter, Summer 2005" (2005). Animal Science Department News. 10. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/animalscinews/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Animal Science Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Animal Science Department News by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Animal Science Animal Science Department ALUMNI NEWSLETTER P.O. Box 830908 • Lincoln, NE 68583-0908 Phone (402) 472-3571 • Web: animalscience.unl.edu Summer 2005 University of Nebraska–Lincoln Beef Teaching Herds have Interesting History The Foundation Years quite a stir and much favorable publicity for the University of Nebraska and the Department of Animal Husbandry. He was The first mention of beef cattle used for instruction of stu- mounted for exhibition at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposi- dents at the University of Nebraska was about 1874 according tion (World’s Fair) in St. Louis and was subsequently returned to Professor Wm. J. Loeffel’s written history of “Animal Hus- to Lincoln where he was used as a classroom model in Animal bandry Through the Years at the University of Nebraska.” While Husbandry until destroyed by fire in 1931. the University was founded in 1869, and the College of Agricul- ture was established in 1872, it wasn’t until 1874 that the “col- The Purebred Teaching Herds Develop lege farm” was purchased at the current location of the UNL East Campus for $55 per acre. -

U.S. Legislative Branch 86 U.S

U.S. Government in nebraSka 85 U.S. LeGiSLative Branch 86 U.S. Government in nebraSka U.S. LeGiSLative Branch conGreSS1 U.S. Senate: The Capitol, Washington, D.C. 20510, phone (202) 224-3121, website — www.senate.gov U.S. House of Representatives: The Capitol, Washington, D.C. 20515, phone (202) 225-3121, website — www.house.gov The Congress of the United States was created by Article 1, Section 1 of the U.S. Constitution, which provides that “All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.” The Senate has 100 members, two from each state, who are elected for six-year terms. There are three classes of senators, and a new class is elected every two years. The House of Representatives has 435 members. The number representing each state is determined by population, and every state is entitled to at least one representative. Members are elected for two-year terms, all terms running for the same period. Senators and representatives must be residents of the state from which they are chosen. In addition, a senator must be at least 30 years old and must have been a U.S. citizen for at least nine years. A representative must be at least 25 years old and must have been a citizen for at least seven years. Nebraska’s Congressional Delegates Nebraska has two senators and three representatives based on recent U.S. Census figures. In the past, the number of Nebraska representatives has been as few as one and as many as six.