EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 10.6.2020 SWD(2020)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release Changes to the List of Euro Foreign Exchange Reference

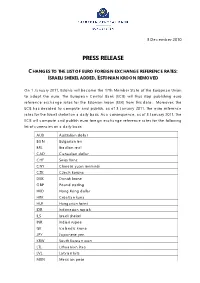

3 December 2010 PRESS RELEASE CHANGES TO THE LIST OF EURO FOREIGN EXCHANGE REFERENCE RATES: ISRAELI SHEKEL ADDED, ESTONIAN KROON REMOVED On 1 January 2011, Estonia will become the 17th Member State of the European Union to adopt the euro. The European Central Bank (ECB) will thus stop publishing euro reference exchange rates for the Estonian kroon (EEK) from this date. Moreover, the ECB has decided to compute and publish, as of 3 January 2011, the euro reference rates for the Israeli shekel on a daily basis. As a consequence, as of 3 January 2011, the ECB will compute and publish euro foreign exchange reference rates for the following list of currencies on a daily basis: AUD Australian dollar BGN Bulgarian lev BRL Brazilian real CAD Canadian dollar CHF Swiss franc CNY Chinese yuan renminbi CZK Czech koruna DKK Danish krone GBP Pound sterling HKD Hong Kong dollar HRK Croatian kuna HUF Hungarian forint IDR Indonesian rupiah ILS Israeli shekel INR Indian rupee ISK Icelandic krona JPY Japanese yen KRW South Korean won LTL Lithuanian litas LVL Latvian lats MXN Mexican peso 2 MYR Malaysian ringgit NOK Norwegian krone NZD New Zealand dollar PHP Philippine peso PLN Polish zloty RON New Romanian leu RUB Russian rouble SEK Swedish krona SGD Singapore dollar THB Thai baht TRY New Turkish lira USD US dollar ZAR South African rand The current procedure for the computation and publication of the foreign exchange reference rates will also apply to the currency that is to be added to the list: The reference rates are based on the daily concertation procedure between central banks within and outside the European System of Central Banks, which normally takes place at 2.15 p.m. -

Public Opinion in Bulgaria in 2018: EU Membership and Further Integration

Policy brief June 2018 Public opinion in Bulgaria in 2018: EU membership and further integration Marin Lessenski, Open Society Institute – Sofia www.osis.bg Contents Introduction and summary of the findings ................................................................................................... 2 Results concerning EU membership ............................................................................................................. 3 Assessment of EU membership .................................................................................................................... 4 Advantages of EU membership ..................................................................................................................... 5 Support to parties that would want leaving the EU ..................................................................................... 7 Support to further integration: Eurozone membership ............................................................................... 8 Comparison between questions about Eurozone membership and replacing the lev with the euro ........ 10 Support to further integration: Schengen membership ............................................................................. 12 Trust in institutions and the EU .................................................................................................................. 12 Results according to profiles of the respondents ....................................................................................... 13 June 2018 Public -

Exchange Market Pressure on the Croatian Kuna

EXCHANGE MARKET PRESSURE ON THE CROATIAN KUNA Srđan Tatomir* Professional article** Institute of Public Finance, Zagreb and UDC 336.748(497.5) University of Amsterdam JEL F31 Abstract Currency crises exert strong pressure on currencies often causing costly economic adjustment. A measure of exchange market pressure (EMP) gauges the severity of such tensions. Measuring EMP is important for monetary authorities that manage exchange rates. It is also relevant in academic research that studies currency crises. A precise EMP measure is therefore important and this paper re-examines the measurement of EMP on the Croatian kuna. It improves it by considering intervention data and thresholds that ac- count for the EMP distribution. It also tests the robustness of weights. A discussion of the results demonstrates a modest improvement over the previous measure and concludes that the new EMP on the Croatian kuna should be used in future research. Key words: exchange market pressure, currency crisis, Croatia 1 Introduction In an era of increasing globalization and economic interdependence, fixed and pegged exchange rate regimes are ever more exposed to the danger of currency crises. Integrated financial markets have enabled speculators to execute attacks more swiftly and deliver devastating blows to individual economies. They occur when there is an abnormally large international excess supply of a currency which forces monetary authorities to take strong counter-measures (Weymark, 1998). The EMS crisis of 1992/93 and the Asian crisis of 1997/98 are prominent historical examples. Recently, though, the financial crisis has led to severe pressure on the Hungarian forint and the Icelandic kronor, demonstrating how pressure in the foreign exchange market may cause costly economic adjustment. -

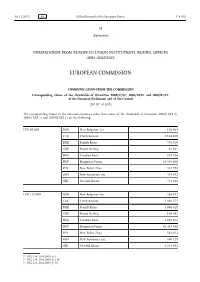

Corresponding Values of the Thresholds of Directives 2004/17/EC, 2004/18/EC and 2009/81/EC, of the European Parliament and of the Council (2015/C 418/01)

16.12.2015 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 418/1 II (Information) INFORMATION FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES EUROPEAN COMMISSION COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION Corresponding values of the thresholds of Directives 2004/17/EC, 2004/18/EC and 2009/81/EC, of the European Parliament and of the Council (2015/C 418/01) The corresponding values in the national currencies other than euros of the thresholds of Directives 2004/17/EC (1), 2004/18/EC (2) and 2009/81/EC (3) are the following: EUR 80 000 BGN New Bulgarian Lev 156 464 CZK Czech Koruna 2 184 400 DKK Danish Krone 596 520 GBP Pound Sterling 62 842 HRK Croatian Kuna 610 024 HUF Hungarian Forint 24 549 600 PLN New Polish Zloty 333 992 RON New Romanian Leu 355 632 SEK Swedish Krona 731 224 EUR 135 000 BGN New Bulgarian Lev 264 033 CZK Czech Koruna 3 686 175 DKK Danish Krone 1 006 628 GBP Pound Sterling 106 047 HRK Croatian Kuna 1 029 416 HUF Hungarian Forint 41 427 450 PLN New Polish Zloty 563 612 RON New Romanian Leu 600 129 SEK Swedish Krona 1 233 941 (1) OJ L 134, 30.4.2004, p. 1. (2) OJ L 134, 30.4.2004, p. 114. (3) OJ L 216, 20.8.2009, p. 76. C 418/2 EN Official Journal of the European Union 16.12.2015 EUR 209 000 BGN New Bulgarian Lev 408 762 CZK Czech Koruna 5 706 745 DKK Danish Krone 1 558 409 GBP Pound Sterling 164 176 HRK Croatian Kuna 1 593 688 HUF Hungarian Forint 64 135 830 PLN New Polish Zloty 872 554 RON New Romanian Leu 929 089 SEK Swedish Krona 1 910 323 EUR 418 000 BGN New Bulgarian Lev 817 524 CZK Czech Koruna 11 413 790 DKK -

Bulgaria Economy Briefing: BULGARIA on HER WAY to the EUROZONE – CURRENT STATUS, POSITIVE and NEGATIVE IMPACTS Evgeniy Kandilarov

ISSN: 2560-1601 Vol. 17, No. 2 (BG) April 2019 Bulgaria economy briefing: BULGARIA ON HER WAY TO THE EUROZONE – CURRENT STATUS, POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE IMPACTS Evgeniy Kandilarov 1052 Budapest Petőfi Sándor utca 11. +36 1 5858 690 Kiadó: Kína-KKE Intézet Nonprofit Kft. [email protected] Szerkesztésért felelős személy: Chen Xin Kiadásért felelős személy: Huang Ping china-cee.eu 2017/01 BULGARIA ON HER WAY TO THE EUROZONE – CURRENT STATUS, POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE IMPACTS One of the very substantial things with a serious financial and economic impact that has been planned to happen in 2019 is the Bulgaria to join t the so called Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM2) as well as the European Banking Union as a precondition of the entrance of country in the Eurozone. The ERM II is the European Central Bank’s exchange rate mechanism, sometimes referred to as the “waiting room” for the Euro. Bulgaria’s government approved on July 18 2018 the formal application for close co-operation with the European central bank (ECB), the first step towards joining the ERM II. The agreement on ERM II preparation includes several additional commitments, which will help support financial sector supervision, improve SOE governance, and strengthen the anti-money laundering (AML) framework. Completing these commitments and joining ERM II and the banking union would further underpin the credibility of policies, in addition to many benefits that the EU membership has brought. The "Eurozone waiting room" is a jargon that appeared about 20 years ago. The idea is that when countries did not have a very fixed exchange rate between themselves before entering the euro, they had a minimum of 2 years of preparatory period in which the exchange rates were expected, the interest rates to get closer. -

Market Wrap-Up Th July 19 2018

MARKET WRAP-UP JULY 19TH 2018 Bulgaria MACRO 120 Bulgaria submits official application for 115 cooperation with ECB 110 Bulgaria has submitted official application for 105 cooperation with the European Central Bank, according to announcement published by the Ministry of Finance. This 100 step comes after the Eurogroup gave Bulgaria the greenlight th to proceed with its application to ERM II on 12 Jul’18. 95 All EU members, currently not part of the Eurozone, have to collaborate with ECB prior to enter the Banking Union and 90 ERM II. The collaboration will take between 6 and 12 months 85 during which time ECB will supervise the Bulgarian banking system. The institution will also propose changes to the local 80 banking legislation in order to adapt it to European regulations. SOFIX Index MXFMCE Index (EUR) State-owned railway transport company BDZ to get Source: Bloomberg subsidy of up to BGN 100m in 2020, according to local OVERALL MARKET DATA media sources. The state aid will be used for the purchase Total Market Cap: 9.4bn of new trains. The media quoted transport minister Ivaylo Total Turnover (FY 2017, regulated market) 705.9m Moskovski who said that BDZ’ indebtedness currently stays at about BGN 100m, down from BGN 800m. He also added Average Daily Turnover (FY 2017, regulated market) 2.85m that part of the money from upcoming Sofia airport Figures are in Bulgarian lev /BGN/ Source: Bulgarian Stock Exchange concession will be used to cut down on BDZ’ debts. MARKET MULTIPLES Index Last 6M%∆ 12M%∆ P/E P/B D/Y SOFIX 628.47 -10.15% -11.62% -

WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates

The WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates The WM/Refinitiv Closing Exchange Rates are available on Eikon via monitor pages or RICs. To access the index page, type WMRSPOT01 and <Return> For access to the RICs, please use the following generic codes :- USDxxxFIXz=WM Use M for mid rate or omit for bid / ask rates Use USD, EUR, GBP or CHF xxx can be any of the following currencies :- Albania Lek ALL Austrian Schilling ATS Belarus Ruble BYN Belgian Franc BEF Bosnia Herzegovina Mark BAM Bulgarian Lev BGN Croatian Kuna HRK Cyprus Pound CYP Czech Koruna CZK Danish Krone DKK Estonian Kroon EEK Ecu XEU Euro EUR Finnish Markka FIM French Franc FRF Deutsche Mark DEM Greek Drachma GRD Hungarian Forint HUF Iceland Krona ISK Irish Punt IEP Italian Lira ITL Latvian Lat LVL Lithuanian Litas LTL Luxembourg Franc LUF Macedonia Denar MKD Maltese Lira MTL Moldova Leu MDL Dutch Guilder NLG Norwegian Krone NOK Polish Zloty PLN Portugese Escudo PTE Romanian Leu RON Russian Rouble RUB Slovakian Koruna SKK Slovenian Tolar SIT Spanish Peseta ESP Sterling GBP Swedish Krona SEK Swiss Franc CHF New Turkish Lira TRY Ukraine Hryvnia UAH Serbian Dinar RSD Special Drawing Rights XDR Algerian Dinar DZD Angola Kwanza AOA Bahrain Dinar BHD Botswana Pula BWP Burundi Franc BIF Central African Franc XAF Comoros Franc KMF Congo Democratic Rep. Franc CDF Cote D’Ivorie Franc XOF Egyptian Pound EGP Ethiopia Birr ETB Gambian Dalasi GMD Ghana Cedi GHS Guinea Franc GNF Israeli Shekel ILS Jordanian Dinar JOD Kenyan Schilling KES Kuwaiti Dinar KWD Lebanese Pound LBP Lesotho Loti LSL Malagasy -

Croatian Kuna: Money, Or Just a Currency? Evidence from the Interbank Market

Davor Mance, Bojana Olgic Drazenovic, and Stella Suljic Nikolaj. 2019. Croatian Kuna: Money, or just a Currency? Evidence from the Interbank Market. UTMS Journal of Economics 10 (2): 149–161. Original scientific paper (accepted November 6, 2019) CROATIAN KUNA: MONEY, OR JUST A CURRENCY? EVIDENCE FROM THE INTERBANK 1 MARKET Davor Mance2 Bojana Olgic Drazenovic Stella Suljic Nikolaj Abstract Modern sovereign money is accepted as an institution in virtue of the collective intentionality of the acceptance of the sovereign status function declaration it being the official currency of a country. A status function declaration may not create money it may only create a currency. How does one test the fact that an official currency also has all the properties of money? We propose a rather simple test based on the Granger causality of the acceptance of a currency in virtue of money if, and only if, the allocation function of its market interest rate is not rejected. This condition is fulfilled if the interest rate is its genuine allocator. This is the case if the changes in quantity cause the change in the interest rate as a price of money i.e. its true opportunity cost. We find that market interest rate changes are Granger caused by changes in quantities of traded euros on the overnight banking market but not by changes in the quantity of traded Croatian kuna. Thus, the Croatian kuna is only the domestic currency of Croatia, and the euro is its true money. Keywords: money functions, euroization, ZIBOR, Granger causality. Jel Classification: E31; E43; E47; E52; G17 INTRODUCTION The fact that we call something “money” is observer relative: it only exists relative to its users and relative to the users’ perspective considering something a money. -

Currencies of the European Union. Eurozone European Union

CURRENCIES OF THE EUROPEAN UNION. EUROZONE EUROPEAN UNION The European Union (EU) is an economic and political union of 28 member states which are located primarily in Europe. The EU traces its origins from the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) and the European Economic Community (EEC), formed by six countries in 1958. CURRENCIES OF THE EUROPEAN UNION As of 2015 there are 11 currencies; The principal currency - Euro (used by 19 members of the EU – Eurozone); All but 2 states are obliged to adopt the currency: Denmark and the United Kingdom, through a legal opt-out from the EU treaties, have retained the right to operate independent currencies within the European Union. The remaining 8 states must adopt the Euro eventually. CURRENCIES OF THE EUROPEAN UNION № Currency Region Year Euro adoption plans 1 Euro Eurozone 1999/2002 Also used by the institutions 2 Bulgarian lev Bulgaria 2007 No target date for euro adoption British pound sterling United Kingdom 3 1973 Opt-out Gibraltar pound Gibraltar 4 Croatian kuna Croatia 2013 No target date for euro adoption 5 Czech koruna Czech Republic 2004 No target date for euro adoption 6 Danish krone Denmark 1973 Opt-out 7 Hungarian forint Hungary 2004 No target date for euro adoption 8 Polish złoty Poland 2004 No target date for euro adoption 9 Romanian leu Romania 2007 Official target date: 1 January 2019 10 Swedish krona Sweden 1995 Pending referendum approval Also unofficially used in Büsingen Campione 11 Swiss franc 1957 am Hochrhein, Germany. Swiss d'Italia(Italy) Franc is issued by Switzerland. EUROZONE The European Union consists of those countries that meet certain membership and accession criteria. -

Political Economy of Croatian Membership

O licencima - Creative Commons https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=hr CC BY-ND Ova licenca dopušta redistribuiranje, komercijalno i nekomercijalno, dokle god se djelo distribuira cjelovito i u neizmijenjenom obliku, uz isticanje Vašeg autorstva. Pogledajte sažetak licence (Commons Deed) | Pogledajte Pravni tekst licence Imenovanje-Nekomercijalno CC BY-NC Ova licenca dopušta drugima da remiksiraju, mijenjaju i prerađuju Vaše djelo u nekomercijalne svrhe. Iako njihova nova djela bazirana na Vašem moraju Vas navesti kao autora i biti nekomercijalna, ona pritom ne moraju biti licencirana pod istim uvjetima. Pogledajte sažetak licence (Commons Deed) | Pogledajte Pravni tekst licence Imenovanje-Nekomercijalno-Dijeli pod istim uvjetima CC BY-NC-SA Lučev, J., et al.: Economic policy independence in EU member states: Political economy of Croatian membership Ova licenca dopušta drugima da remiksiraju, mijenjaju i prerađuju Vaše djelo u Josip Lučev Dario Cvrtila JEL: E580, E650,nekomercijalne H620, N140 svrhe, pod uvjetom da Vas navedu kao autora izvornog djela i University of Zagreb Libertas International University Review article Faculty of Political Science 10000 Zagreb, Croatia https://doi.org/10.51680/ev.34.1.17licenciraju svoja djela nastala na bazi Vašeg pod istim uvjetima. 10000 Zagreb, Croatia [email protected] [email protected] Received: February 13, 2020 Revision received:Pogledajte July 14, 2020 sažetak licence (Commons Deed) | Pogledajte Pravni tekst licence Accepted for publishing: August 31, 2020 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License Imenovanje-Nekomercijalno-Bez prerada CC BY-NC-ND ECONOMIC POLICY INDEPENDENCE IN EU MEMBER Ovo je najrestriktivnija od naših šest osnovnih licenci – dopušta drugima da STATES: POLITICAL ECONOMY5 od 6 26. -

Econometric Analysis of Croatia's Proclaimed

South East European Journal of Economics and Business Volume 10 (1) 2015, 7-17 DOI: 10.1515/jeb-2015-0001 ECONOMETRIC ANALYSIS OF CROATIA’S PROCLAIMED FOREIGN EXCHANGE RaTE Davor Mance, Saša Žiković, Diana Mance * Abstract The officially proclaimed foreign exchange policy of the Croatian National Bank (CNB) is a managed float with a discretionary right of intervention on the Croatian kuna/euro foreign exchange (FX) market in order to maintain price stability. This paper examines the validity of three monetary policy hypotheses: the stabil- ity of the nominal exchange rate, the stability of exchange rate changes, and the exchange rate to inflation pass-through effect. The CNB claims a direct FX to inflation rate pass-through channel for which we find no evidence, but we find a strong link between FX rate changes and changes in M4, as well as between M4 changes and inflation. Changes in foreign investment Granger cause changes in monetary aggregates that further Granger cause inflation. Changes in FX rate Granger cause a reaction in M4 that indirectly Granger causes a further rise in inflation. Vector Autoregression Impulse Response Functions of changes in FX rate, M1, M4, and CPI confirm the Granger causalities in the established order. Keywords: central bank policies, monetary transmission effects, inflation targeting JEL classification: C22, E52, E58, F42 INTRODUCTION * Davor Mance, MA The Croatian National Bank (CNB) has recently Assistant changed its official policy from a free floating to a University of Rijeka, Faculty of Economics managed floating exchange regime (CNB 2013, CNB [email protected] 2014). The CNB reserves the right to intervene on the currency markets and it did so more than 200 times in Žiković, Saša, PhD an 18 years period (1997-2014). -

Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/1580

Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/1580. (See end of Document for details) Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/1580 of 19 October 2018 amending Implementing Regulation (EU) 2015/2197 laying down implementing technical standards with regard to closely correlated currencies in accordance with Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council (Text with EEA relevance) COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2018/1580 of 19 October 2018 amending Implementing Regulation (EU) 2015/2197 laying down implementing technical standards with regard to closely correlated currencies in accordance with Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council (Text with EEA relevance) THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms and amending Regulation (EU) No 648/2012(1) and in particular Article 354(3) thereof, Whereas: (1) In order to ensure that the currency pairs referred to in the Annex to Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2015/2197(2) continue to reflect the actual correlation between the relevant currencies, it is necessary to update the list of closely correlated currencies. (2) The list uses 31 March 2017 as the end date for the purpose of computing the three and five year data series required to assess the currency pairs in accordance with Regulation (EU) No 575/2013. (3) This Regulation is based on the draft implementing technical standards submitted by the European Banking Authority (EBA) to the Commission.