Caught up in Catch Shares

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estimation of Antimicrobial Activities and Fatty Acid Composition Of

Estimation of antimicrobial activities and fatty acid composition of actinobacteria isolated from water surface of underground lakes from Badzheyskaya and Okhotnichya caves in Siberia Irina V. Voytsekhovskaya1,*, Denis V. Axenov-Gribanov1,2,*, Svetlana A. Murzina3, Svetlana N. Pekkoeva3, Eugeniy S. Protasov1, Stanislav V. Gamaiunov2 and Maxim A. Timofeyev1 1 Irkutsk State University, Irkutsk, Russia 2 Baikal Research Centre, Irkutsk, Russia 3 Institute of Biology of the Karelian Research Centre of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Petrozavodsk, Karelia, Russia * These authors contributed equally to this work. ABSTRACT Extreme and unusual ecosystems such as isolated ancient caves are considered as potential tools for the discovery of novel natural products with biological activities. Acti- nobacteria that inhabit these unusual ecosystems are examined as a promising source for the development of new drugs. In this study we focused on the preliminary estimation of fatty acid composition and antibacterial properties of culturable actinobacteria isolated from water surface of underground lakes located in Badzheyskaya and Okhotnichya caves in Siberia. Here we present isolation of 17 strains of actinobacteria that belong to the Streptomyces, Nocardia and Nocardiopsis genera. Using assays for antibacterial and antifungal activities, we found that a number of strains belonging to the genus Streptomyces isolated from Badzheyskaya cave demonstrated inhibition activity against Submitted 23 May 2018 bacteria and fungi. It was shown that representatives of the genera Nocardia and Accepted 24 September 2018 Nocardiopsis isolated from Okhotnichya cave did not demonstrate any tested antibiotic Published 25 October 2018 properties. However, despite the lack of antimicrobial and fungicidal activity of Corresponding author Nocardia extracts, those strains are specific in terms of their fatty acid spectrum. -

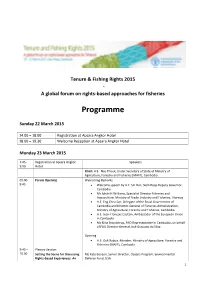

A Global Forum on Rights-Based Approaches for Fisheries

Tenure & Fishing Rights 2015 - A global forum on rights-based approaches for fisheries Programme Sunday 22 March 2015 14.00 – 18.00 Registration at Apsara Angkor Hotel 18.00 – 19.30 Welcome Reception at Apsara Angkor Hotel Monday 23 March 2015 7:45- Registration at Apsara Angkor Speakers 9:00 Hotel Chair: H.E. Nao Thuok, Under Secretary of State of Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF), Cambodia 09:00- Forum Opening Welcoming Remarks 9:45 Welcome speech by H.E. Sin Run, Siem Reap Deputy Governor, Cambodia Mr Johán H Williams, Specialist Director Fisheries and Aquaculture, Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries, Norway H.E. Eng Chea San, Delegate of the Royal Government of Cambodia and Director-General of Fisheries Administration, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Cambodia H.E. Jean-François Cautain, Ambassador of the European Union in Cambodia Ms Nina Brandstrup, FAO Representative in Cambodia, on behalf of FAO Director-General José Graziano da Silva Opening H.E. Ouk Rabun, Minister, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF), Cambodia 9:45 – Plenary Session: 10.30 Setting the Scene for Discussing Ms Kate Bonzon, Senior Director, Oceans Program, Environmental Rights-based Experiences: An Defense Fund, USA 1 overview An overview of the types of user rights and how they may conserve fishery resources and provide food security, contribute to poverty eradication, and lead to development of fishing communities. 10.30- Plenary: Question and Answer 11:00 session Moderator: Mr Georges Dehoux, Attaché, Cooperation Section, Delegation of the European Union in the Kingdom of Cambodia and Co- Chair of the Cambodia Technical Working Group on Fisheries 11:00- Plenary session: Cambodia’s Ms Kaing Khim, Deputy Director General, Fisheries Administration, 11:30 experience with rights-based Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Cambodia approaches: the social, economic and environmental aspects of developing and implementing a user rights system 11:30- Plenary session: A[nother] Asian Mr Dedi S. -

Career Guide Cover.Indd

Food Law and Policy Career Guide For anyone interested in an internship or a career in food law and policy, this guide illustrates many of the diverse array of choices, whether you seek a traditional legal job or would like to get involved in research, advocacy, or policy-making within the food system. 2nd Edition Summer 2013 Researched and Prepared by: Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic Emily Broad Leib, Director Allli Condra, Clinical Fellow Harvard Food Law and Policy Division Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation Harvard Law School 122 Boylston Street Jamaica Plain, MA 02130 [email protected] www.law.harvard.edu/academics/clinical/lsc Harvard Food Law Society Cristina Almendarez, Grant Barbosa, Rachel Clark, Kate Schmidt, Erin Schwartz, Lauren Sidner Harvard Law School www3.law.harvard.edu/orgs/foodlaw/ Special Thanks to: Louisa Denison Kathleen Eutsler Caitlin Foley Adam Jaffee Annika Nielsen Kate Olender Niousha Rahbar Adam Soliman Note to Readers: This guide is a work in progress and will be updated, corrected, and expanded over time. If you want to include additional organizations or suggest edits to any of the current listings, please email [email protected]. 2 table of contents an introduction to food law and policy ........................................................................................................................... 4 guide to areas of specialization .......................................................................................................................................... 5 section -

Felicia Wu, Ph.D

FELICIA WU, PH.D. John A. Hannah Distinguished Professor Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics Michigan State University 204 Trout FSHN Building, 469 Wilson Rd, East Lansing, MI 48824 Tel: 1-517-432-4442 Fax: 1-517-353-8963 [email protected] EDUCATION 1998 Harvard University A.B., S.M., Applied Mathematics & Medical Sciences 2002 Carnegie Mellon University Ph.D., Engineering & Public Policy APPOINTMENTS & POSITIONS 2013-present John A. Hannah Distinguished Professor, Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition, Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI . Director, Center for Health Impacts of Agriculture (CHIA) . Core Faculty, Center for Integrative Toxicology . Core Faculty, International Institute of Health . Core Faculty, Center for Gender in Global Context 2011-2013 Associate Professor, Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA . Secondary Faculty, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine . Secondary Faculty, Graduate School of Public and International Affairs . Core Faculty, Center for Research on Health Care . Secondary Faculty, Center for Bioethics and Health Law . Faculty Advisory Board, European Union Center for Excellence 2004-2011 Assistant Professor, Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 2002-2004 Associate Policy Researcher, RAND, Pittsburgh, PA RESEARCH AND TEACHING Fields Food Safety, Food Security, Global Health and the Environment, Mycotoxins, Agricultural Health, Agricultural Biotechnology, Climate Change, Indoor Air Quality Methods Economics, Mathematical Modeling, Quantitative Risk Assessment, Risk Communication, Policy Analysis AWARDS & HONORS . The National Academies: National Research Council (NRC) Committee on Considerations for the Future of Animal Science Research, 2014-2015 . -

What If California's Drought Continues?

August 2015 PPIC WATER POLICY CENTER What If California’s Drought Continues? Ellen Hanak Jeffrey Mount Caitrin Chappelle Jay Lund Josué Medellín-Azuara Peter Moyle Nathaniel Seavy Research support from Emma Freeman, Jelena Jedzimirovic, Henry McCann, and Adam Soliman Supported with funding from the California Water Foundation, an initiative of the Resources Legacy Fund Summary California is in the fourth year of a severe, hot drought—the kind that is increasingly likely as the climate warms. Although no sector has been untouched, impacts so far have varied greatly, reflecting different levels of drought preparedness. Urban areas are in the best shape, thanks to sustained investments in diversified water portfolios and conservation. Farmers are more vulnerable, but they are also adapting. The greatest vulnerabilities are in some low-income rural communities where wells are running dry and in California’s wetlands, rivers, and forests, where the state’s iconic biodiversity is under extreme threat. Two to three more years of drought will increase challenges in all areas and require continued—and likely increasingly difficult—adaptations. Emergency programs will need to be significantly expanded to get drinking water to rural residents and to prevent major losses of waterbirds and extinctions of numerous native fish species, including most salmon runs. California also needs to start a longer-term effort to build drought resilience in the most vulnerable areas. Introduction In 2015, California entered the fourth year of a severe drought. Although droughts are a regular feature of the state’s climate, the current drought is unique in modern history. Taken together, the past four years have been the driest since record keeping began in the late 1800s.1 This drought has also been exceptionally warm (Figure 1). -

Liquid Business

Florida State University Law Review Volume 47 Issue 1 In Tribute to Talbot "Sandy" D'Alemberte Article 9 Fall 2019 Liquid Business Vanessa C. Perez Texas A&M School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons Recommended Citation Vanessa C. Perez, Liquid Business, 47 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 201 (2019) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol47/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIQUID BUSINESS VANESSA CASADO PEREZ* Water is scarcer due to climate change and in higher demand due to population growth than ever before. As if these stressors were not concerning enough, corporate investors are participating in water mar- kets in ways that sidestep U.S. water law doctrine’s aims of preventing speculation and assuring that the holders of water rights internalize any externalities associated with changes in their rights. The operation of these new players in the shadow of traditional water law is produc- ing elements of inefficiency and unfairness in the allocation of water rights. Resisting the polar calls for unfettered water markets, or, con- trarily, the complete de-commodification of water in the face of these challenges, this Article identifies a portfolio of measures that can help get regulated water markets back on a prudent, sustainable track in our contemporary world. -

What If California's Drought Continues?

August 2015 PPIC WATER POLICY CENTER What If California’s Drought Continues? Ellen Hanak Jeffrey Mount Caitrin Chappelle Jay Lund Josué Medellín-Azuara Peter Moyle Nathaniel Seavy Research support from Emma Freeman, Jelena Jedzimirovic, Henry McCann, and Adam Soliman Supported with funding from the California Water Foundation, an initiative of the Resources Legacy Fund Summary California is in the fourth year of a severe, hot drought—the kind that is increasingly likely as the climate warms. Although no sector has been untouched, impacts so far have varied greatly, reflecting different levels of drought preparedness. Urban areas are in the best shape, thanks to sustained investments in diversified water portfolios and conservation. Farmers are more vulnerable, but they are also adapting. The greatest vulnerabilities are in some low-income rural communities where wells are running dry and in California’s wetlands, rivers, and forests, where the state’s iconic biodiversity is under extreme threat. Two to three more years of drought will increase challenges in all areas and require continued—and likely increasingly difficult—adaptations. Emergency programs will need to be significantly expanded to get drinking water to rural residents and to prevent major losses of waterbirds and extinctions of numerous native fish species, including most salmon runs. California also needs to start a longer-term effort to build drought resilience in the most vulnerable areas. Introduction In 2015, California entered the fourth year of a severe drought. Although droughts are a regular feature of the state’s climate, the current drought is unique in modern history. Taken together, the past four years have been the driest since record keeping began in the late 1800s.1 This drought has also been exceptionally warm (Figure 1). -

UNIVERSITY CONVOCATION Wednesday, September 9, 2015

New Jersey Institute of Technology UNIVERSITY CONVOCATION Wednesday, September 9, 2015 Program PROCESSIONAL MODERATOR Fadi P. Deek ’85, ’86, ’97 Provost and Senior Executive Vice President NATIONAL ANTHEM WELCOME TO THE FRESHMAN CLASS STATE OF THE UNIVERSITY ADDRESS Joel Stuart Bloom President KEYNOTE ADDRESS Owen Fitzgerald ’08 RECOGNITION OF NEWLY PROMOTED/TENURED FACULTY Vincent DeCaprio ’72 Vice Chair, Board of Trustees RECOGNITION OF AWARDS ALMA MATER RECESSIONAL 1 Award Recipients Presidential Leadership Awards Excellence in Research Awards John Canela ’15 Tara Alvarez Computer Science Biomedical Engineering Pitambar Dayal ’16 Burt Kimmelman Biomedical Engineering Humanities Songhua Xu Excellence in Teaching Awards Information Systems UNDERGRADUATE INSTRUCTION, UPPER DIVISION Ecevit Bilgili Overseers Excellence in Research Prize And Medal Chemical, Biological and Pharmaceutical Engineering Haimin Wang Physics UNDERGRADUATE INSTRUCTION, LOWER DIVISION David Horntrop Mathematics Constance A. Murray Diversity Award Jo-Ann Raines GRADUATE INSTRUCTION Career Services Edward Dreyzin Chemical, Biological and Pharmaceutical Engineering Panasonic Chair in Sustainability INSTRUCTION BY A UNIVERSITY LECTURER Reggie Caudill Kyle Riismandel Management History INSTRUCTION BY AN ADJUNCT PROFESSOR Daniel Kopec College of Architecture and Design INSTRUCTION BY A TEACHING ASSISTANT Regina Collins Information Systems EXCELLENCE IN TEACHING HONORS COURSES Ellen Wisner Biological Sciences EXCELLENCE IN INNOVATIVE TEACHING Davida Scharf Humanities 2 Newly -

LIQUID BUSINESS Vanessa Casado Perez*

LIQUID BUSINESS Vanessa Casado Perez* There are plenty of forces pushing water to be the new oil as it becomes scarcer due to climate change and increases in demand as a result of population growth and lifestyle changes. These forces may be unstoppable. In addition to traditional water rights exchanges, water markets include, among others, large multinational conglomerates bidding for our water utilities, investment in water reuse, and specialized investment funds purchasing interests in water-related companies. These lucrative investments in water sidestep traditional water law doctrines aimed at preventing speculation and ensuring that externalities are internalized, are profiting from regulatory gaps, and many perceive them as commodifying and corporatizing an essential and common good—water. Scholarship on water markets broadly understood is either in favor of free markets or set against any form of market. This article instead offers a portfolio of measures to ensure that water markets are properly regulated. Water markets can be a positive tool for water management ensuring that scarce water ends up in the hands of those who value it the most. This does not need to come at the expense of the fulfilment of the human right to water, the community of origin, or the environment. Among the measures analyzed, there is the joint management of surface and groundwater and the limit on who can hold a water right and how much water can a water right holder be entitled to. Mark Twain purportedly said that, “Whisky is for drinking and water is for fighting.” Water scarcity will certainly cause fights as there will not be enough water for all users. -

Career Guide Cover.Indd

Food Law and Policy Career Guide For anyone interested in an internship or a career in food law and policy, this guide illustrates many of the diverse array of choices, whether you seek a traditional legal job or would like to get involved in research, advocacy, or policy-making within the food system. 2nd Edition Summer 2013 Researched and Prepared by: Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic Emily Broad Leib, Director Allli Condra, Clinical Fellow Harvard Food Law and Policy Division Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation Harvard Law School 122 Boylston Street Jamaica Plain, MA 02130 [email protected] www.law.harvard.edu/academics/clinical/lsc Harvard Food Law Society Cristina Almendarez, Grant Barbosa, Rachel Clark, Kate Schmidt, Erin Schwartz, Lauren Sidner Harvard Law School www3.law.harvard.edu/orgs/foodlaw/ Special Thanks to: Louisa Denison Kathleen Eutsler Caitlin Foley Adam Jaffee Annika Nielsen Kate Olender Niousha Rahbar Adam Soliman Note to Readers: This guide is a work in progress and will be updated, corrected, and expanded over time. If you want to include additional organizations or suggest edits to any of the current listings, please email [email protected]. 2 table of contents an introduction to food law and policy ........................................................................................................................... 4 guide to areas of specialization .......................................................................................................................................... 5 section -

Download The

Impacts of Individual Transferable Quotas in Canadian Sablefish Fisheries: An Economic Analysis by Adam Soliman BSc. , Alexandria University, 1999 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Science in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Agriculture Economics) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) July 2010 © Adam Soliman, 2010 Abstract In 1990, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans implemented the Individual Transferable Quotas (ITQ) system to achieve its management goals. The purpose of this study is to investigate the effectiveness of this system. It aims to determine whether and how the ITQ system creates an economically viable industry; what problems the ITQ system has generated and what factors should be considered in addressing them; and what the risk of holding these quotas is to the fisher. To this end, I will focus on efficiency as a critical dimension of economic viability and the fisher’s competitiveness. I will begin by comparing the ITQ to the Limited Entry system which preceded it and explore claims regarding the impact of ITQs on the sustainability and viability of fishing firms and the sablefish fishery. Next, I will conduct a detailed and comprehensive analysis of the industry’s cost structure that highlights the value/purchase price of the quota, which is widely considered to be a crude measure of industry profitability. This analysis will examine Barichello’s (1996) model in order to calculate the risk associated with holding sablefish quotes and Monk and Pearson’s (1989) Policy Analysis Matrix (PAM) in order to determine whether the sablefish industry is efficient. -

Updated 2/11/2013

updated 2/11/2013 - 1 - Welcome! Welcome to the Public Interest Environmental Law Conference (PIELC), the premier annual gathering for environmentalists in the world! Now in its 32nd year, PIELC unites thousands of activists, attorneys, students, scientists, and community members from over 50 countries around the globe to share their ideas, experience, and expertise. With keynote addresses, workshops, films, celebrations, and over 130 panels, PIELC is world-renowned for its energy, innovation, and inspiration. In 2011, PIELC received the Program of the Year Award from the American Bar Association Section of Environment, Energy, and Resources, and in 2013 PIELC received the American Bar Assoication Law Student Division’s Public Interest Award. PIELC 2014, RunnIng Into RunnIng out “Running Into Running Out” conveys a sense of urgency that we must take greater action to avoid running out of the resources necessary for survival, and we must do it now. Our best scientists warn that continuing on our business-as-usual trajectory will place life as we know it amidst unpredictable, and essentially irreversible, planetary catastrophe. These are not fun facts to face. They beg for a long and sober assessment of the race humanity is running into: the destruction of the planet and those who call it home. They call for a course change and reorientation to rapidly changing circumstances. This year’s Conference will be a space for critical assessment of past strategies and discussion of new solutions dedicated to ending the destruction. We are running out of time, and we are running out of options, but we have not run out yet.