Commodity and Relational Good Exchanges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estimation of Antimicrobial Activities and Fatty Acid Composition Of

Estimation of antimicrobial activities and fatty acid composition of actinobacteria isolated from water surface of underground lakes from Badzheyskaya and Okhotnichya caves in Siberia Irina V. Voytsekhovskaya1,*, Denis V. Axenov-Gribanov1,2,*, Svetlana A. Murzina3, Svetlana N. Pekkoeva3, Eugeniy S. Protasov1, Stanislav V. Gamaiunov2 and Maxim A. Timofeyev1 1 Irkutsk State University, Irkutsk, Russia 2 Baikal Research Centre, Irkutsk, Russia 3 Institute of Biology of the Karelian Research Centre of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Petrozavodsk, Karelia, Russia * These authors contributed equally to this work. ABSTRACT Extreme and unusual ecosystems such as isolated ancient caves are considered as potential tools for the discovery of novel natural products with biological activities. Acti- nobacteria that inhabit these unusual ecosystems are examined as a promising source for the development of new drugs. In this study we focused on the preliminary estimation of fatty acid composition and antibacterial properties of culturable actinobacteria isolated from water surface of underground lakes located in Badzheyskaya and Okhotnichya caves in Siberia. Here we present isolation of 17 strains of actinobacteria that belong to the Streptomyces, Nocardia and Nocardiopsis genera. Using assays for antibacterial and antifungal activities, we found that a number of strains belonging to the genus Streptomyces isolated from Badzheyskaya cave demonstrated inhibition activity against Submitted 23 May 2018 bacteria and fungi. It was shown that representatives of the genera Nocardia and Accepted 24 September 2018 Nocardiopsis isolated from Okhotnichya cave did not demonstrate any tested antibiotic Published 25 October 2018 properties. However, despite the lack of antimicrobial and fungicidal activity of Corresponding author Nocardia extracts, those strains are specific in terms of their fatty acid spectrum. -

Working Paper No. 222

Money and Taxes: The Chartalist L. Randall Wray” Working Paper No. 222 January 1998 *Senior Scholar, The Jerome Levy Economics Institute L. Rnndull Wray Introductory Quotes “A requirement that certain taxes should be paid in particular paper money might give that paper a certain value even if it was irredeemable.” (Edwin Cannan, Marginal Summary to page 3 12 of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, in Smith 1937: 3 12) “[T]he money of a State is not what is of compulsory general acceptance, but what is accepted at the public pay offices...” (Knapp 1924: vii) “Money is the creation of the state; it is not true to say that gold is international currency, for international contracts are never made in terms of gold, but always in terms of some national monetary unit; there is no important distinction between notes and metallic money.... ” Keynes (Keynes 1983: 402) “In an economy where government debt is a major asset on the books of the deposit- issuing banks, the fact that taxes need to be paid gives value to the money of the economy. The virtue of a balanced budget and a surplus insofar as the commodity value (purchasing power) of money is concerned is that the need to pay taxes means that people work and produce in order to get that in which taxes can be paid.” (Minsky 1986: 23 1) *****k*************X*********************~***********~****** Introduction In conventional analysis, money is used to facilitate exchange; its value was long determined by the value of the precious metal it represented, although under a fiat money system, its value is determined by the quantity of commodities it can purchase. -

Commodity Dependence and International Commodity Prices

commoDity DEpEndencE anD intErnational 2 commoDity pricEs Since low-income coutries depend mostly on just a few commodities for the bulk share of their export earnings, commodity price fluctuations directly affect the incidence of poverty, as the vast majority of the poor depend on primary commodities for their livelihoods. Photo: Martine Perret/UN Timor-Leste MartinePhoto: Perret/UN Commodity Dependence and International Commodity Prices Introduction The types of commodities exported by a country are another important determinant of a country’s vulnerability to exogenous economic shocks. The majority of developing countries are dependent on primary commodities1 for export revenues and, of the 141 developing countries, 95 depend on primary commodities for at least 50 percent of their export earnings (Brown 2008). However, international commodity prices are notoriously volatile in the short to medium term, sometimes varying by as much as 50 percent in a single year (South Centre 2005). Moreover, price volatility is increasing over time and across a broad range of commodities. “In the past 30 years, there have been as many price shocks across the range of commodities as there were in the preceding 75 years” (Brown 2008). From the perspective of developing countries, especially those whose principal means of foreign exchange earnings come from Over the longer term, dependence the exports of primary commodities, unstable commodity prices on primary commodities heightens create macro-economic instabilities and complicate macro- a country’s vulnerability because economic management. Erratic price movements generate erratic movements in export revenue, cause instability in foreign exchange (non-oil) primary commodity prices reserves and are strongly associated with growth volatility. -

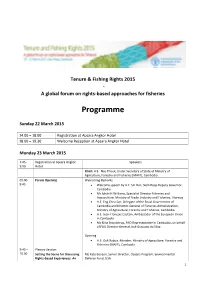

A Global Forum on Rights-Based Approaches for Fisheries

Tenure & Fishing Rights 2015 - A global forum on rights-based approaches for fisheries Programme Sunday 22 March 2015 14.00 – 18.00 Registration at Apsara Angkor Hotel 18.00 – 19.30 Welcome Reception at Apsara Angkor Hotel Monday 23 March 2015 7:45- Registration at Apsara Angkor Speakers 9:00 Hotel Chair: H.E. Nao Thuok, Under Secretary of State of Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF), Cambodia 09:00- Forum Opening Welcoming Remarks 9:45 Welcome speech by H.E. Sin Run, Siem Reap Deputy Governor, Cambodia Mr Johán H Williams, Specialist Director Fisheries and Aquaculture, Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries, Norway H.E. Eng Chea San, Delegate of the Royal Government of Cambodia and Director-General of Fisheries Administration, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Cambodia H.E. Jean-François Cautain, Ambassador of the European Union in Cambodia Ms Nina Brandstrup, FAO Representative in Cambodia, on behalf of FAO Director-General José Graziano da Silva Opening H.E. Ouk Rabun, Minister, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF), Cambodia 9:45 – Plenary Session: 10.30 Setting the Scene for Discussing Ms Kate Bonzon, Senior Director, Oceans Program, Environmental Rights-based Experiences: An Defense Fund, USA 1 overview An overview of the types of user rights and how they may conserve fishery resources and provide food security, contribute to poverty eradication, and lead to development of fishing communities. 10.30- Plenary: Question and Answer 11:00 session Moderator: Mr Georges Dehoux, Attaché, Cooperation Section, Delegation of the European Union in the Kingdom of Cambodia and Co- Chair of the Cambodia Technical Working Group on Fisheries 11:00- Plenary session: Cambodia’s Ms Kaing Khim, Deputy Director General, Fisheries Administration, 11:30 experience with rights-based Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Cambodia approaches: the social, economic and environmental aspects of developing and implementing a user rights system 11:30- Plenary session: A[nother] Asian Mr Dedi S. -

Money As 'Universal Equivalent' and Its Origins in Commodity Exchange

MONEY AS ‘UNIVERSAL EQUIVALENT’ AND ITS ORIGIN IN COMMODITY EXCHANGE COSTAS LAPAVITSAS DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF LONDON [email protected] MAY 2003 1 1.Introduction The debate between Zelizer (2000) and Fine and Lapavitsas (2000) in the pages of Economy and Society refers to the conceptualisation of money. Zelizer rejects the theorising of money by neoclassical economics (and some sociology), and claims that the concept of ‘money in general’ is invalid. Fine and Lapavitsas also criticise the neoclassical treatment of money but argue, from a Marxist perspective, that ‘money in general’ remains essential for social science. Intervening, Ingham (2001) finds both sides confused and in need of ‘untangling’. It is worth stressing that, despite appearing to be equally critical of both sides, Ingham (2001: 305) ‘strongly agrees’ with Fine and Lapavitsas on the main issue in contention, and defends the importance of a theory of ‘money in general’. However, he sharply criticises Fine and Lapavitsas for drawing on Marx’s work, which he considers incapable of supporting a theory of ‘money in general’. Complicating things further, Ingham (2001: 305) also declares himself ‘at odds with Fine and Lapavitsas’s interpretation of Marx’s conception of money’. For Ingham, in short, Fine and Lapavitsas are right to stress the importance of ‘money in general’ but wrong to rely on Marx, whom they misinterpret to boot. Responding to these charges is awkward since, on the one hand, Ingham concurs with the main thrust of Fine and Lapavitsas and, on the other, there is little to be gained from contesting what Marx ‘really said’ on the issue of money. -

MLP & Infrastructure

Monthly Investment Commentary April 2021 Midstream: Last month, we discussed how midstream has historically provided inflation- resistant income in a way that REITs, utilities, and TIPS have not. Q1 earnings provided a strong case-in-point for this relationship, as midstream profited from commodity bottlenecks, while other sectors absorbed higher costs. This week’s Colonial Pipeline outage is another example of how underinvestment has created less infrastructure redundancy. The fundamental arguments for midstream – benefitting operationally from inflation, while reducing capital employed at a time of rising rates – continue to strengthen, especially compared to capital-intensive sectors like utilities and Cleantech. Natural Resources: As current inflationary pressures mount, the topic of 1970s inflation has grown in prominence. Our analysis of the 1970s highlights the stronger role commodities played in the early 1970s inflationary period, compared to the broader based inflation of the late 1970s. With commodity inflation increasing today in the relative absence of broad-based inflation, at this point, the early 1970s appears to be a more appropriate comparison than the late 1970s and could foreshadow an extended period of inflation. MLP & Infrastructure Performance review During the month of April 2021, the Recurrent MLP & Infrastructure Strategy generated net returns of +5.62%, underperforming the +7.15% return of the Alerian MLP Index (AMZ) by (1.53%). Since the strategy’s July 2017 inception, Recurrent’s MLP & Infrastructure Strategy has outperformed the AMZ by +3.74% (annualized, net of fees). Please see the performance section at bottom for more detail. One year since WTI oil prices went negative, commodity bottlenecks are increasingly frequent From oil and gas, to lumber, copper, steel and aluminum – commodity tightness is making itself felt across the global economy. -

Career Guide Cover.Indd

Food Law and Policy Career Guide For anyone interested in an internship or a career in food law and policy, this guide illustrates many of the diverse array of choices, whether you seek a traditional legal job or would like to get involved in research, advocacy, or policy-making within the food system. 2nd Edition Summer 2013 Researched and Prepared by: Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic Emily Broad Leib, Director Allli Condra, Clinical Fellow Harvard Food Law and Policy Division Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation Harvard Law School 122 Boylston Street Jamaica Plain, MA 02130 [email protected] www.law.harvard.edu/academics/clinical/lsc Harvard Food Law Society Cristina Almendarez, Grant Barbosa, Rachel Clark, Kate Schmidt, Erin Schwartz, Lauren Sidner Harvard Law School www3.law.harvard.edu/orgs/foodlaw/ Special Thanks to: Louisa Denison Kathleen Eutsler Caitlin Foley Adam Jaffee Annika Nielsen Kate Olender Niousha Rahbar Adam Soliman Note to Readers: This guide is a work in progress and will be updated, corrected, and expanded over time. If you want to include additional organizations or suggest edits to any of the current listings, please email [email protected]. 2 table of contents an introduction to food law and policy ........................................................................................................................... 4 guide to areas of specialization .......................................................................................................................................... 5 section -

Felicia Wu, Ph.D

FELICIA WU, PH.D. John A. Hannah Distinguished Professor Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics Michigan State University 204 Trout FSHN Building, 469 Wilson Rd, East Lansing, MI 48824 Tel: 1-517-432-4442 Fax: 1-517-353-8963 [email protected] EDUCATION 1998 Harvard University A.B., S.M., Applied Mathematics & Medical Sciences 2002 Carnegie Mellon University Ph.D., Engineering & Public Policy APPOINTMENTS & POSITIONS 2013-present John A. Hannah Distinguished Professor, Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition, Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI . Director, Center for Health Impacts of Agriculture (CHIA) . Core Faculty, Center for Integrative Toxicology . Core Faculty, International Institute of Health . Core Faculty, Center for Gender in Global Context 2011-2013 Associate Professor, Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA . Secondary Faculty, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine . Secondary Faculty, Graduate School of Public and International Affairs . Core Faculty, Center for Research on Health Care . Secondary Faculty, Center for Bioethics and Health Law . Faculty Advisory Board, European Union Center for Excellence 2004-2011 Assistant Professor, Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 2002-2004 Associate Policy Researcher, RAND, Pittsburgh, PA RESEARCH AND TEACHING Fields Food Safety, Food Security, Global Health and the Environment, Mycotoxins, Agricultural Health, Agricultural Biotechnology, Climate Change, Indoor Air Quality Methods Economics, Mathematical Modeling, Quantitative Risk Assessment, Risk Communication, Policy Analysis AWARDS & HONORS . The National Academies: National Research Council (NRC) Committee on Considerations for the Future of Animal Science Research, 2014-2015 . -

What If California's Drought Continues?

August 2015 PPIC WATER POLICY CENTER What If California’s Drought Continues? Ellen Hanak Jeffrey Mount Caitrin Chappelle Jay Lund Josué Medellín-Azuara Peter Moyle Nathaniel Seavy Research support from Emma Freeman, Jelena Jedzimirovic, Henry McCann, and Adam Soliman Supported with funding from the California Water Foundation, an initiative of the Resources Legacy Fund Summary California is in the fourth year of a severe, hot drought—the kind that is increasingly likely as the climate warms. Although no sector has been untouched, impacts so far have varied greatly, reflecting different levels of drought preparedness. Urban areas are in the best shape, thanks to sustained investments in diversified water portfolios and conservation. Farmers are more vulnerable, but they are also adapting. The greatest vulnerabilities are in some low-income rural communities where wells are running dry and in California’s wetlands, rivers, and forests, where the state’s iconic biodiversity is under extreme threat. Two to three more years of drought will increase challenges in all areas and require continued—and likely increasingly difficult—adaptations. Emergency programs will need to be significantly expanded to get drinking water to rural residents and to prevent major losses of waterbirds and extinctions of numerous native fish species, including most salmon runs. California also needs to start a longer-term effort to build drought resilience in the most vulnerable areas. Introduction In 2015, California entered the fourth year of a severe drought. Although droughts are a regular feature of the state’s climate, the current drought is unique in modern history. Taken together, the past four years have been the driest since record keeping began in the late 1800s.1 This drought has also been exceptionally warm (Figure 1). -

Commodity Value Measurement and Connotative Value Currency

Theoretical Economics Letters, 2020, 10, 535-544 https://www.scirp.org/journal/tel ISSN Online: 2162-2086 ISSN Print: 2162-2078 Commodity Value Measurement and Connotative Value Currency Jinjun Cheng1, Dian Cheng2 1Anhui Development and Reform Commission, Hefei, China 2Pudong Development Bank Hefei Branch, Hefei, China How to cite this paper: Cheng, J. J., & Abstract Cheng, D. (2020). Commodity Value Mea- surement and Connotative Value Currency. Goods of utility, in the final analysis, contain two parts of natural value and Theoretical Economics Letters, 10, 535-544. labor value: the natural value is created by god and given to us for free, the https://doi.org/10.4236/tel.2020.103034 labor value is the human labor which is condensed in the commodity without Received: April 26, 2020 any difference, and the commodity value is reflected by the labor value. The Accepted: May 24, 2020 essence of human labor is the process of consuming the energy and life time Published: May 27, 2020 of the body and doing physical work to the object of labor. The value of labor, W, is the square root of the product of the energy consumed by the worker, E, Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. and the time spent on labor, T (W = ET ). By discovering the formula of This work is licensed under the Creative commodity labor value, we can design a new currency that conforms to the Commons Attribution International principles of freedom and fairness—the Talent (symbol: Ω|| ), whose value License (CC BY 4.0). || http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ corresponds to its value: 1 Ω = 1 JS⋅ , J is joules, S is seconds. -

Liquid Business

Florida State University Law Review Volume 47 Issue 1 In Tribute to Talbot "Sandy" D'Alemberte Article 9 Fall 2019 Liquid Business Vanessa C. Perez Texas A&M School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons Recommended Citation Vanessa C. Perez, Liquid Business, 47 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 201 (2019) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol47/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIQUID BUSINESS VANESSA CASADO PEREZ* Water is scarcer due to climate change and in higher demand due to population growth than ever before. As if these stressors were not concerning enough, corporate investors are participating in water mar- kets in ways that sidestep U.S. water law doctrine’s aims of preventing speculation and assuring that the holders of water rights internalize any externalities associated with changes in their rights. The operation of these new players in the shadow of traditional water law is produc- ing elements of inefficiency and unfairness in the allocation of water rights. Resisting the polar calls for unfettered water markets, or, con- trarily, the complete de-commodification of water in the face of these challenges, this Article identifies a portfolio of measures that can help get regulated water markets back on a prudent, sustainable track in our contemporary world. -

Abstract Labor: Substance Or Form

ABSTRACT LABOR: SUBSTANCE OR FORM ABSTRACT LABOR: SUBSTANCE OR FORM? A CRITIQUE OF THE VALUE-FORM INTERPRETATION OF MARX’S THEORY by Fred Moseley Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana (Mexico City) Mount Holyoke College (Massachusetts) May 1997 Our analysis has shown that the form of value, that is the expression of the value of a commodity, arises from the nature of commodity value, as opposed to value and its magnitude arising from their mode of expression as exchange-value. Marx (C. I. 152) It is not money that renders commodities commensurable. Quite the contrary. Because all commodities, as values, are objective human labor and therefore themselves commensurable, their values can be communally measured in one and the same commodity. Mon ey is the necessary form of appearance of the measure of value immanent in commodities - labor-time. Marx (C.I. 188) ABSTRACT LABOR: SUBSTANCE OR FORM? A CRITIQUE OF THE VALUE-FORM INTERPRETATION OF MARX’S THEORY In the Introduction to our first book, I wrote: All the authors agree that Marx attempted in Section 1 of Chapter 1 of Capital to derive abstract labor as the "substance of value," which exists prior to exchange - although it is not observable - and which determines the exchange values of com modities. But there is significant disagreement over the validity file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/mhcuserxp/Desktop/VALUEFRM.htm (1 of 15)10/15/2005 2:29:42 PM ABSTRACT LABOR: SUBSTANCE OR FORM and necessity of Marx’s derivation. Indeed this disagreement is probably the most significant one amount the authors. This controversy has a long history beginning with Boehm-Bawerk.