Diederik Cuckoo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Short Communications

Short Communications The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 118(1):99±101, 2006 Provisioning of Fledgling Conspeci®cs by Males of the Brood-parasitic Cuckoos Chrysococcyx klaas and C. caprius Irby J. Lovette,1,4 Dustin R. Rubenstein,1,2,3 and Wilson Nderitu Watetu3 ABSTRACT.ÐAlthough post-¯edging care by adult Over the past century, there have been nu- males seems unlikely in bird species that are obligate, merous observations of male Chrysococcyx interspeci®c brood parasites, there have been numer- cuckoos feeding conspeci®cs that were ous reports of adult male Chrysococcyx cuckoos ap- parently feeding conspeci®c young. Most researchers thought to be ¯edglings (Moreau 1944, Fried- currently view these observations with skepticism, in mann 1968, Iversen and Hill 1983, Rowan large part because Chrysococcyx and other cuckoo spe- 1983). In a literature review of provisioning cies engage in courtship feeding, and it is possible that behavior in brood parasites, Lorenzana and ®eld observers could mistake adult females receiving Sealy (1998) found 5 records of nestling or food from courting males for ¯edglings, especially giv- en the similar appearances of females and juveniles. ¯edgling provisioning by Klaas's Cuckoo Here, we report an observation of an extended provi- males and 11 such records for Diederik Cuck- sioning bout by an adult male Klaas's Cuckoo (C. oo males; Friedmann (1968) discusses 12 and klaas) feeding a conspeci®c individual with juvenile 15 such records, respectively, including some plumage and behavior, and we summarize our obser- anecdotal reports. There is apparently only vations of similar occurrences in the Diederik Cuckoo one equivalent report of a female Chrysococ- (C. -

Chrysococcyx Lucidus) in New Zealand

249 Notornis, 2013, Vol. 60: 249-251 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. SHORT NOTE Observation of food presentation behaviour between individual shining cuckoos (Chrysococcyx lucidus) in New Zealand M.N.H. SEABROOK-DAVISON* M.G. ANDERSON Ecology, Behaviour and Conservation Group, Institute of Natural and Mathematical Sciences, Massey University, Private Bag 102904, Auckland 0745, New Zealand Little is known about courtship behaviour in the ensure a rapid onset of breeding condition in female shining cuckoo (Chrysococcyx lucidus) (also known cuckoos. as Chalcites lucidus) and whether males feed females The shining cuckoo is an obligate specialist brood as occurs in a number of other species. Although parasite that only uses the grey warbler (Gerygone there have been a number of observations of male igata) as a host species on the main islands of New Chrysococcyx cuckoos feeding suspected conspecific Zealand (Heather & Robertson 1996; Gill 1983b) and fledglings (Moreau 1944; Friedmann 1968; Iversen the Chatham Island warbler (Gerygone albofrontata) & Hill 1983; Lovette et al. 2006), more recently it on the Chatham Is (Dennison et al. 1984). Little has been suggested that these were misdirected has been recorded of the courtship behaviour of courtship feeding or the observers misidentified the shining cuckoo. Seabrook-Davison et al. (2008) adult female cuckoos as fledglings (Lorenzana described pre-copulatory behaviour and copulation & Sealy 1998; Davies 2000). If this is the case, in a pair of shining cuckoos at Coatesville, 28 km these observations may be indicative of courtship north of Auckland, New Zealand. This behaviour behaviours and that courtship feeding occurs more was observed only once during 5 minute bird-count frequently than previous appreciated. -

Does Coevolution with a Shared Parasite Drive Hosts to Partition Their

Downloaded from http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on August 29, 2017 Does coevolution with a shared parasite rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org drive hosts to partition their defences among species? Eleanor M. Caves1, Martin Stevens2 and Claire N. Spottiswoode1,3 Research 1Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EJ, UK 2 Cite this article: Caves EM, Stevens M, Centre for Ecology and Conservation, College of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Exeter, Penryn Campus, Penryn, Cornwall TR10 9FE, UK Spottiswoode CN. 2017 Does coevolution with 3DST-NRF Centre of Excellence at the FitzPatrick Institute, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, a shared parasite drive hosts to partition their South Africa defences among species? Proc. R. Soc. B 284: EMC, 0000-0003-3497-5925; MS, 0000-0001-7768-3426; CNS, 0000-0003-3232-9559 20170272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.0272 When mimicry imposes costs on models, selection may drive the model’s phenotype to evolve away from its mimic. For example, brood parasitism often drives hosts to diversify in egg appearance among females within a species, making mimetic parasitic eggs easier to detect. However, when a Received: 9 February 2017 single parasite species exploits multiple host species, parasitism could also Accepted: 19 April 2017 drive host egg evolution away from other co-occurring hosts, to escape suscep- tibility to their respective mimics. This hypothesis predicts that sympatric hosts of the same parasite should partition egg phenotypic space (defined by egg colour, luminance and pattern) among species to avoid one another. We show that eggs of warbler species parasitized by the cuckoo finch Anoma- Subject Category: lospiza imberbis in Zambia partition phenotypic space much more distinctly Evolution than do eggs of sympatric but unparasitized warblers. -

The Gambia in Style – Photography Special

The Gambia in Style – Photography Special Naturetrek Tour Report 24 November - 1 December 2017 Brown-throated Wattle Eye Diederic Cuckoo Little Bee-eater Pied Kingfisher Report and images by Kevin Elsby Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report The Gambia in Style – Photography Special Tour participants: Kevin Elsby (leader) with eight Naturetrek clients Day 1 Friday 24th November The group assembled at Gatwick for the 10.30am Titan Air flight to Banjul in the Gambia. After a comfortable 6 ½-hour flight, we met up again in the arrivals area to collect our bags, then change cash into the local currency, before boarding the air-conditioned coach which would take us to the Mandina Lodges, our base for the next seven nights. On arrival, after a 45-minute journey, we were warmly greeted by Linda and her staff and made instantly welcome. The setting for the lodges is truly special being in a natural area of forest adjacent to a tributary of the Gambia river. It has its own landing jetty as part of the property. It was getting dark by the time we arrived and so after a refreshing cold drink we were escorted to our accommodation, where we were able to unpack and prepare for our excellent evening meal, all freshly prepared for us. On our way from the airport to Mandina we were able to pick out a single Yellow-billed Kite and a couple of Hooded Vultures as well five very distinctive Pied Crows. -

Evolution of Bird Eggs in the Absence of Cuckoo Parasitism

Evolution of bird eggs in the absence of cuckoo parasitism David C. Lahti* Museum of Zoology and Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 Communicated by Richard D. Alexander, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, October 12, 2005 (received for review March 3, 2004) Historical introductions of species into new habitats can create rare weavers in West Africa, and observed their responses. Birds opportunities to test evolutionary hypotheses, such as the role of rejected eggs in proportion to differences in color and spotting natural selection in maintaining traits. This study examines two pattern between the foreign eggs and their own. independent introductions of the African village weaverbird (Plo- To maximize effectiveness of egg rejection behavior as a ceus cucullatus) to islands where selection on egg appearance traits defense against brood parasitism, a village weaver’s eggs should is expected to differ markedly from that of the source populations. possess two features. First, they should be distinctive within the The color and spotting of village weaver eggs in Africa are highly population; weaver eggs should have high between-individual consistent within clutches, but highly variable between individu- variation, as indeed they do in Africa (9, 15). Although no als. These two features may be an evolutionary response to brood quantitative comparative study has yet been performed, the level parasitism. In Africa, weavers are parasitized by each other and by of population variability in egg appearance found in African the diederik cuckoo (Chrysococcyx caprius), an egg mimic. African Ploceus weavers is extreme among birds. The more unusual a village weavers were introduced one century ago to Mauritius, and weaver egg is in its population, the more likely a parasitic egg laid over two centuries ago to Hispaniola. -

Persistence of Passerine Ectoparasites on the Diederik Cuckoo Chrysococcyx Caprius

J. Zool., Lond. (1998) 244, 145±153 # 1998 The Zoological Society of London Printed in the United Kingdom Persistence of passerine ectoparasites on the diederik cuckoo Chrysococcyx caprius Anna K. Lindholm1*, Gert J. Venter2 and Edward A. Ueckermann3 1 Department of Zoology, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EJ, U.K. and Department of Zoology & Entomology, University of Natal, Private Bag X01, Scottsville 3209, South Africa 2 Onderstepoort Veterinary Institute, Private Bag X5, Onderstepoort 0110, South Africa 3 Plant Protection Research Institute, Private Bag X134, Pretoria 0001, South Africa (Accepted 3 June 1997) Abstract Using the African diederik cuckoo Chrysococcyx caprius and four sympatric passerine foster species in the subfamily Ploceinae, we show that nestling cuckoos are infested by feather lice and mites derived from the ectoparasite fauna typical of the foster species. Adult cuckoos had ®ve species of lice and mites normally found on ploceines, which demonstrates that these ectoparasites are able to survive on foreign hosts. This is the ®rst record of persistence of passerine ectoparasites on a cuckoo. Adult diederik cuckoos also harboured four species of mites and lice speci®c to cuckoos; since these were not detected on nestlings, cuckoo-speci®c lice and mites apparently transfer to cuckoos after they leave the nest. Contrary to prediction, ectoparasites with a life cycle involving a permanent association with their host (feather mites and lice) were more likely to transfer to cuckoo nestlings than ectoparasites which spend part of their life cycle away from their host (haematophagous mites and phoretic skin mites). New host records are established for the lice genera Brueelia, Cuculoecus, Machaerilaemus, Myrsidea, Philopterus as well as for the mite species Microlichus americanus, Ornithonyssus bursa, Ornithocheyla megaphallos, Pellonyssus reedi, Pteronyssoides passeris, Pternonyssus glossifer, Trouessartia baupi, T. -

Nieuwsbrief Sectie Hymenoptera

nummer 20 april 2020 Nieuwsbrief Sectie Hymenoptera Nederlandse Entomologische Vereniging In dit nummer onder meer: Verslagen excursies 2019 Veldobservaties Waarnemingen aan nesten van Eucera longicornis op Texel De goudwesp Chrysurus austriaca in Zuid-Limburg ‘Binokenmerken’ documenteren met macrofotografie Het genus Proctotrupes in Nederland nr. 20, april 2020 ISSN 1387-1773 Foto voorpagina: Proctotrupes gravidator. Foto: Sipke Wadman. Nieuwsbrief sectie Hymenoptera van de Nederlandse Entomologische Vereniging Vormgeving: Jan Smit. Redactie J. D’Haeseleer, T. Peeters, J. Smit, E. van der Spek Redactieadres Voermanstraat 14, 6921 NP Duiven e-mail: [email protected] Website www.hymenovaria.nl Redactioneel De seCtie groeit en dat is te merken aan het aantal Uit het buitenland de Hymenopterologen-Tagung in leden dat een bijdrage aanlevert voor de nieuwsbrief. Stuttgart en de bij van het jaar in Duitsland. Het is een boordevol nummer geworden! !! Vanwege de CoronaCrisis is de voorjaarsexcursie Bij ‘Oproepen’ de bekende vraag van de versChoven naar volgend jaar!! penningmeester om de bijdrage van dit jaar te betalen, een oproep om gestylopiseerde aculeaten te Om te beginnen de aankondiging van de zomer- verzamelen en de vraag om mee te doen aan het excursie van dit jaar. Dan een viertal verslagen: van de bodemnestelregister. Verder een oproep om uit te studiedag, de exCursies van 2019 en een symposium. kijken naar de ogentroostdikpoot De rubriek Leuke waarnemingen’’ is goed gevuld. En er is een viertal veldobservaties. Er zijn enkele mededelingen, met daarin een aangekondigde bestuurswijziging, het jaarverslag van Bij de ‘Artikelen’een negental bijdragen, met een de seCtie en aCtiviteiten van anderen. veelheid aan onderwerpen; van uitgegraven nesten, de naamgeving van bijen, gynandromorfen, goudwespen, Jorgen Ravoet wordt hartelijk bedankt voor het jonge hommelkoninginnen en sluipwespen van het vertalen van enkele samenvattingen in het Engels. -

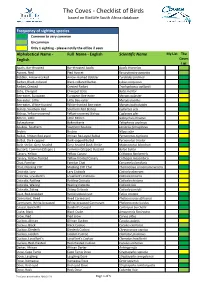

Checklist of Birds Based on Birdlife South Africa Database

The Coves - Checklist of Birds based on BirdLife South Africa database Frequency of sighting species Common to very common Uncommon Only 1 sighting - please notify the office if seen Slegs 1 waarneming - stel asb die kantoor in kennis Alphabetical Name - Full Name - English Scientific Name My List The English Coves List Apalis, Bar-throated Bar-throated Apalis Apalis thoracica 2 Avocet, Pied Pied Avocet Recurvirostra avosetta 2 Babbler, Arrow-marked Arrow-marked Babbler Turdoides jardineii 4 Barbet, Black-collared Black-collared Barbet Lybius torquatus 5 Barbet, Crested Crested Barbet Trachyphonus vaillantii 5 Batis, Chinspot Chinspot Batis Batis molitor 2 Bee-eater, European European Bee-eater Merops apiaster 1 Bee-eater, Little Little Bee-eater Merops pusillus 1 Bee-eater, White-fronted White-fronted Bee-eater Merops bullockoides 4 Bishop, Southern Red Southern Red Bishop Euplectes orix 5 Bishop, Yellow-crowned Yellow-crowned Bishop Euplectes afer 1 Bittern, Little Little Bittern Ixobrychus minutus 1 Bokmakierie Bokmakierie Telophorus zeylonus 1 Boubou, Southern Southern Boubou Laniarius ferrugineus 5 Brubru Brubru Nilaus afer 1 Bulbul, African Red-eyed African Red-eyed Bulbul Pycnonotus nigricans 1 Bulbul, Dark-capped Dark-capped Bulbul Pycnonotus tricolor 4 Bush-shrike, Grey-headed Grey-headed Bush-Shrike Malaconotus blanchoti 3 Buzzard, Common (Steppe ) Common (Steppe) Buzzard Buteo buteo 1 Canary, Yellow Yellow Canary Crithagra flaviventris 1 Canary, Yellow-fronted Yellow-fronted Canary Crithagra mozambica 3 Chat, Familiar Familiar -

Visual Trickery in Avian Brood Parasites

CHAPTER 6 Visual trickery in avian brood parasites N aomi E . L angmore and C laire N . S pottiswoode 6. 1 Introduction into rearing its young. Thus we generally see the most advanced parasite recognition systems Visual mimicry is a strategy deployed by a wide amongst hosts of evicting parasites, which in turn range of taxa, from spiders that mimic the ants they select for highly accurate visual mimicry by para- hunt ( Nelson and Jackson 2006 ), to cross-dressing sites to evade host detection. males in bluegill sunfi sh ( Dominey 1980 ), and However, host defenses are not the only selective harmless snakes that mimic the vibrant colors of agent responsible for the evolution of visual mimicry venomous snakes ( Harper and Pfenning 2008 ) (see in brood parasites. Mimicry can also arise to facilitate Chapter 11 ). Although visual mimicry is wide- exploitation of parent–offspring channels of commu- spread amongst invertebrates, and to a lesser extent nication, ensuring that the parasite chick is able to fi sh, amphibians, and reptiles ( Ruxton et al. 2004 ), elicit adequate care from its foster parents (parasite it is generally a rare phenomenon among birds (but “tuning,” Davies 2011 ). Mimicry for this purpose is see e.g., Dumbacher and Fleischer 2001 ). However, equally likely to arise in evicting and non-evicting the avian brood parasites provide a notable excep- parasites, and was termed sequential evolution mim- tion. Several recent fi eld studies, combined with icry by Grim ( 2005 ), to distinguish it from mimicry new techniques for quantifying mimicry and mod- that arises through a coevolutionary arms race. -

How Precise Is Egg Discrimination in Weaverbirds?

ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR, 2002, 63, 1135–1142 doi:10.1006/anbe.2002.3009, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on How precise is egg discrimination in weaverbirds? DAVID C. LAHTI & APRIL R. LAHTI Department of Biology and Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan (Received 3 August 2000; initial acceptance 19 December 2000; final acceptance 20 November 2001; MS. number: A8847R2) The village weaverbird, Ploceus cucullatus, lays eggs of an extremely broad range of appearance between individuals. This variation is thought to have evolved as a counteradaptation to brood parasitism by the diederik cuckoo Chrysococcyx caprius. The primary objective of our study was to characterize the relationship between egg appearance and egg rejection in the African village weaverbird. We test predictions of three hypotheses in a study in The Gambia, West Africa: (1) interindividual egg variability permits individuals to discriminate between own and foreign eggs by rejecting eggs in proportion to the difference in appearance from their own; (2) village weavers remember the appearance of their own eggs and do not require a discordancy within their clutch, nor even the presence of one of their own eggs, in order to distinguish a foreign egg as such; and (3) colour and speckling contain the signature information by which village weavers can distinguish their eggs from foreign ones; whereas shape and mass, being less reliable, do not. We analysed rejection behaviour according to egg appearance differences by logistic regression. Results supported all three hypotheses. We estimated the predictive efficacy of our model, the amount of explained variation and the relative contribution of various egg appearance factors to discrimination by the host. -

Ultimate Uganda

This year we watched a pair of Grauer's (or African Green) Broadbill feeding their young in the nest. This parent was bringing fruit. The colour of the bird closely matches the foliage making this a very difficult bird to find away from the nest particularly as the call/song is almost inaudible! (Nik Borrow) ULTIMATE UGANDA 19 JULY – 8 AUGUST 2015 LEADERS: NIK BORROW Uganda is famously quoted as being the ‘Pearl of Africa’ and although neither Henry Morton Stanley nor Winston Churchill had birders and ecotourists in mind when they awarded the country this title it is most certainly an appropriate one! This is surely an essential destination for any world-travelling bird watcher as it is home to the incredible Shoebill, a good number of Albertine Rift endemics and is an excellent place to see a few otherwise difficult western African forest species. A visit to this friendly and welcoming country also offers a great mammal-watching experience and of course primates in particular with Eastern Gorilla and Chimpanzee at the top of the list. It is not often that the mammals get a mention before the birds, but on this 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Uganda www.birdquest-tours.com occasion it is apt, as our experiences with the incredible Eastern Gorillas of Bwindi Impenetrable Forest were truly unforgettable! To rival this experience the incomparable Shoebill surrendered to our collective gaze on day one and we were also lucky to find the often-elusive Weyns’s Weaver nearby. In Mabira Forest we found Yellow-eyed Greenbul and Forest Wood Hoopoes whilst at Kaniyo Pabidi in Murchison Falls National Park Puvel’s Illadopsis entertained and the secretive Nahan’s Francolin put in an appearance. -

Does Coevolution with a Shared Parasite Drive Hosts to Partition Their Defences Among Species?

CORE Downloaded from http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on August 29,Metadata, 2017 citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Apollo Does coevolution with a shared parasite rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org drive hosts to partition their defences among species? Eleanor M. Caves1, Martin Stevens2 and Claire N. Spottiswoode1,3 Research 1Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EJ, UK 2 Cite this article: Caves EM, Stevens M, Centre for Ecology and Conservation, College of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Exeter, Penryn Campus, Penryn, Cornwall TR10 9FE, UK Spottiswoode CN. 2017 Does coevolution with 3DST-NRF Centre of Excellence at the FitzPatrick Institute, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, a shared parasite drive hosts to partition their South Africa defences among species? Proc. R. Soc. B 284: EMC, 0000-0003-3497-5925; MS, 0000-0001-7768-3426; CNS, 0000-0003-3232-9559 20170272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.0272 When mimicry imposes costs on models, selection may drive the model’s phenotype to evolve away from its mimic. For example, brood parasitism often drives hosts to diversify in egg appearance among females within a species, making mimetic parasitic eggs easier to detect. However, when a Received: 9 February 2017 single parasite species exploits multiple host species, parasitism could also Accepted: 19 April 2017 drive host egg evolution away from other co-occurring hosts, to escape suscep- tibility to their respective mimics. This hypothesis predicts that sympatric hosts of the same parasite should partition egg phenotypic space (defined by egg colour, luminance and pattern) among species to avoid one another.