Transferring Spending Power to the Poorest Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Circle District Location Acc Code Name of ACC ACC Address

Sheet1 DISTRICT BRANCH_CD LOCATION CITYNAME ACC_ID ACC_NAME ADDRESS PHONE EMAIL Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3091004 RAJESH KUMAR SHARMA 5849/22 LAKHAN KOTHARI CHOTI OSWAL SCHOOL KE SAMNE AJMER RA9252617951 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3047504 RAKESH KUMAR NABERA 5-K-14, JANTA COLONY VAISHALI NAGAR, AJMER, RAJASTHAN. 305001 9828170836 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3043504 SURENDRA KUMAR PIPARA B-40, PIPARA SADAN, MAKARWALI ROAD,NEAR VINAYAK COMPLEX PAN9828171299 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3002204 ANIL BHARDWAJ BEHIND BHAGWAN MEDICAL STORE, POLICE LINE, AJMER 305007 9414008699 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3021204 DINESH CHAND BHAGCHANDANI N-14, SAGAR VIHAR COLONY VAISHALI NAGAR,AJMER, RAJASTHAN 30 9414669340 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3142004 DINESH KUMAR PUROHIT KALYAN KUNJ SURYA NAGAR DHOLA BHATA AJMER RAJASTHAN 30500 9413820223 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3201104 MANISH GOYAL 2201 SUNDER NAGAR REGIONAL COLLEGE KE SAMMANE KOTRA AJME 9414746796 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3002404 VIKAS TRIPATHI 46-B, PREM NAGAR, FOY SAGAR ROAD, AJMER 305001 9414314295 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3204804 DINESH KUMAR TIWARI KALYAN KUNJ SURYA NAGAR DHOLA BHATA AJMER RAJASTHAN 30500 9460478247 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3051004 JAI KISHAN JADWANI 361, SINDHI TOPDADA, AJMER TH-AJMER, DIST- AJMER RAJASTHAN 305 9413948647 [email protected] -

District Boundary Assembly Constituency

NEW ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES (Based on Rajasthan Gazette Notification SADULSHAHAR-1 Dated 25th January, 2006) GANGANAGAR-2 SANGARIA-7 KARANPUR-3 RAJASTHAN PILIBANGA (SC)-9 HANUMANGARH- 8 GANGANAGAR RAISINGHNAGAR (SC)-5 SURATGARH-4 HANUMANGARH BHADRA-11 NOHAR-10 ® ANUPGARH (SC)-6 TARANAGAR-20 LUNKARANSAR-16 SADULPUR-19 KHAJUWALA SARDARSHAHAR-21 (SC)-12 CHURU PILANI CHURU-22 (SC)-25 BIKANER MANDAWA-28 SURAJGARH-26 JHUNJHUNUN-27 TIJARA-59 JHUNJHUNUN DUNGARGARH-17 BIKANER FATEHPUR-32 WEST-13 KHETRI-31 BEHROR- BIKANER RATANGARH-23 EAST-14 NAWALGARH- 62 MUNDAWAR- 61 29 KISHANGARH KOLAYAT-15 UDAIPURWATI- BAS-60 LACHHMANGARH-33 30 NEEM KA THANA-38 KAMAN-70 SUJANGARH KOTPUTLI-40 (SC)-24 SIKAR-35 BANSUR-63 KHANDELA-37 ALWAR LADNUN- URBAN-66 RAMGARH-67 NOKHA-18 106 DHOD (SC)-34 SIKAR SRIMADHOPUR-39 ALWAR NAGAR-71 ALWAR VIRATNAGAR-41 RURAL (SC)-65 DEEG - DANTA KUMHER-72 RAMGARH-36 KATHUMAR DEEDWANA-107 SHAHPURA-42 PHALODI-122 (SC)-69 JAYAL RAJGARH - (SC)-108 BHARATPUR- NAGAUR- CHOMU-43 THANAGAZI-64 LAXMANGARH (ST)-68 73 109 NADBAI-74 NAWAN- JAISALMER- 115 JAMWA BHARATPUR 132 AMBER-47 MAHUWA-86 NAGAUR MAKRANA- RAMGARH BANDIKUI-85 WEIR 113 (ST)-48 (SC)-75 JAISALMER KHINVSAR-110 JHOTWARA-46 JAIPUR DAUSA- LOHAWAT-123 BAYANA POKARAN- ADARSH 88 NAGAR-53 DAUSA (SC)-76 133 PHULERA-44 SIKRAI RAJAKHERA-80 DEGANA- (SC)-87 HINDAUN 112 PARBATSAR- BASSI (SC)-82 BAGRU 114 (ST)-57 PUSHKAR- (SC)-56 TODABHIM DHOLPUR- JODHPUR 99 (ST)-81 DHAULPUR 79 OSIAN- DUDU BARI-78 125 (SC)-45 CHAKSU KARAULI-83 MERTA (SC)-58 LALSOT BAMANWAS BASERI BHOPALGARH (SC)-111 (ST)-89 (SC)-126 -

Chittorgarh, Rajasthan, India)

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2013): 4.438 Tehsil Wise Study and Analysis of Health Centers using GIS (Chittorgarh, Rajasthan, India) Kawaljeet Singh1, B. L. Pal2 1M. Tech Scholar, Mewar University, Gangrar, Chittorgarh, Rajasthan, India 2Assistant Professor, Department of CSE, Mewar University, Gangrar, Chittorgarh, Rajasthan, India Abstract: Healthcare is the birth right of the citizens of any country. Most of the developed countries have implemented universal healthcare systems. However many developing countries like India are striving for the universal healthcare. The objective of WHO (World Health Organization) is to promote and coordinate healthcare across the world. India has been in close relationship with WHO since 1948 and is committed to provide affordable healthcare to the citizens of its country. For India the biggest challenge is the population . Moreover more than 70% people live in rural areas. The access to primary health care in rural area is very limited. In this direction Indian government launched National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) to improve the healthcare services in the rural areas. Rajasthan is among the 18 states of India which was identified by NRHM with very low healthcare. There many government policies and organizations (NGOs) are being run, still there is need to focus a lot on rural health development programs. The healthcare in India comprises of three tiers, Sub Centre (SC), Primary Health Centre (PHC) and Community Health Centre(CHC) . There are various population norms provided by Ministry of Health for the opening of health centers in the rural areas. -

Ajmer Vidyut Vitran Nigam Limited

Ajmer Vidyut Vitran Nigam Limited Corporate Identification Number (CIN) – U40109RJ2000SGC016482 Registerd Office: Vidyut Bhawan, Panchsheel Nagar, Makarwali Road, Ajmer-305004 e-mail: [email protected] ; Website – www.avvnl.com District / Circle Toll free No. 18001806531 Customer Care Centre, Ajmer 18001806565 Ajmer City Circle/ District Circle 18001806532 Bhilwara 18001806533 Nagaur 18001806534 Jhunjhunu 18001806535 Sikar 18001806536 Chittorgarh 18001806537 Pratapgarh 18001806538 Banswara 18001806539 Dungarpur 18001806540 Rajsamand 18001806541 Udaipur 18001806542 Please select your Circle/ District for viewing the Contact information of Nigam Officers (fuxe vf/kdkfj;ksa ds laidZ tkudkjh ns[kus ds fy, vius ldZy @ftyk p;u djsaA) Ajmer City Circle/ City Ajmer District Circle/ District Bhilwara Circle/ District Nagaur Circle/ District Jhunjhunu Circle/ District Sikar Circle/ District Udaipur Circle/ District Rajsamand Circle/ District Chittorgarh Circle/ District Pratapgarh Circle/ District Dungarpur Circle/ District Banswara Circle/ District RDPPC Wing Accounts Wing Store Wing M&P Wing IT Wing Vigilance Wing Civil Wing Chief Engineer(s) Project Wing Chief Engineer(O&M), Ajmer Chief Engineer(O&M), Jhunjhunu Chief Engineer (O&M), Udaipur Zone Office Zone Office Zone Office Corporate Office Building, AVVNL, Ajmer (Vidhyut Bhawan) Board of Directors Legal Cell Commercial Wing Plan Wing Turnkey Works Wing RGGVY Wing Company Secretary Cell Material Management Wing Administrative Wing Director (Finance) – Personal Cell Director (Technical) – Personal Cell MD Cell/ Office Ajmer Zone Hierarchy (A) SE Ajmer City Circle (B) SE Ajmer Distt. Circle (1) XEN (CD-I), Ajmer (1) XEN (O&M), Kishangarh 1. AEN (CSD-II), Ajmer 1. AEN (O&M), Kishangarh 2. AEN (CSD-III), Ajmer 2. AEN (Rural), Kishangarh 3. AEN (CSD-V), Ajmer 4. -

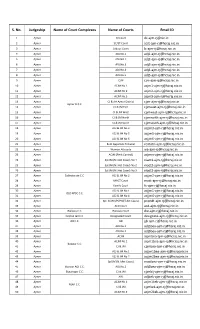

E-Mail Ids of Rajasthan Judiciary

S. No. Judgeship Name of Court Complexes Name of Courts Email ID 1 Ajmer DJ Court [email protected] 2 Ajmer SC/ST Court [email protected] 3 Ajmer Labour Court [email protected] 4 Ajmer ADJ No.1 [email protected] 5 Ajmer ADJ NO.2 [email protected] 6 Ajmer ADJ No.3 [email protected] 7 Ajmer ADJ No.4 [email protected] 8 Ajmer ADJ No.5 [email protected] 9 Ajmer CJM [email protected] 10 Ajmer ACJM No.1 [email protected] 11 Ajmer ACJM No.2 [email protected] 12 Ajmer ACJM No.3 [email protected] 13 Ajmer CJ & JM Ajmer District [email protected] Ajmer D.C.C. 14 Ajmer CJ & JM East [email protected] 15 Ajmer CJ & JM West [email protected] 16 Ajmer CJ & JM North [email protected] 17 Ajmer CJ & JM South [email protected] 18 Ajmer ACJ & JM No.3 [email protected] 19 Ajmer ACJ & JM No.5 [email protected] 20 Ajmer ACJ & JM No.6 [email protected] 21 Ajmer Rent Appellate Tribunal [email protected] 22 Ajmer Women Attrocity [email protected] 23 Ajmer ACJM (Rent Control) [email protected] 24 Ajmer Spl.JM (N.I.Act Cases) No.1 [email protected] 25 Ajmer Spl.JM (N.I.Act Cases) No.2 [email protected] 26 Ajmer Spl.JM (N.I.Act Cases) No.3 [email protected] 27 Ajmer Collectorate C.C. -

CGST Udaipur

Scanned by CamScanner ANNEXURE -A LIST OF GST DIVISIONS & RANGES COMMISSIONERATE NAME: UDAIPUR COMMISSIONERATE CODE: WP Division Code Division Name Division Jurisdiction Division Address WP01 GST Division-A, Udaipur Area of Girwa tehsil Left side from Baleecha By-Pass via Goverdhan Vilas, Railway Station upto Surajpole of 142 B, Sector 11, Hiran Magri, Udaipur 313001 Udaipurcity and Area from left side of Suraj pole to Dabok of Tehsil Girwa. Jhadol, Kotda, Badgaon, Gogunda and Mavli tehsil of Udaipur Distt. Range Code Range Name Range Jurisdiction Range Address WP0101 GST Range-I Left side of Surajpole to starting point of NH-27 (Opp.Pacific Dental College, Debari) via Sevashram, Pratap Nagar 142 B, Sector 11, Hiran Magri, Udaipur 313001 Choraha of Girwa Tehil upto Amberi Pulia to Surajpole via Sukhadia Circle, Chetak Circle and entrire area of Kotda Tehsil and remaing part of Badgaon Tehsil other then mention in Range IV of Udaipur Distt. WP0102 GST Range-II Right side of part of Girwa Tehil starting from Dabok on NH 76 to Amberi Pulia via starting point of NH27 and 142 B, Sector 11, Hiran Magri, Udaipur 313001 Amberi Pulia Nathdwara Road (part of Girwa Tehsil) and entire area of Gogunda Tehsil of Udaipur Distt. WP0103 GST Range-III Left side of NH48 from Baleecha By-Pass via Goverdhan Vilas, Railway Station upto Fatehpura circle via Court 142 B, Sector 11, Hiran Magri, Udaipur 313001 Choraha and from Fatehpura circle to Rampura Circle via Devali, Rani Road, Mahakaleshwar Mandir, Mullatali (Subash Choraha) and from Ram Pura Circle to Nai and back to Baleecha via Sisarma. -

Beawar-Pali-Pindwara Section of Nh-14 in the State of Rajasthan

Intended for L&T Infrastructure Development Projects Limited Document type Final Traffic Report Date September, 2017 TRAFFIC STUDY FOR BEAWAR-PALI-PINDWARA SECTION OF NH-14 IN THE STATE OF RAJASTHAN Traffic Study for Beawar-Pali-Pindwara section of NH-14 in the state of Rajasthan 1 Revision 01 Date 28/09/2017 Made by Ramya/Nitin/Harpreet Checked by Meenakshi Asija Approved by Srinivas Chekuri Description Final Traffic Report Traffic Study for Beawar-Pali-Pindwara section of NH-14 in the state of Rajasthan 2 DISCLAIMER In preparing this report, Ramboll India Private Limited relied, in whole or in part, on data and information provided by the L&T IDPL, which information has not been independently verified by Ramboll and which Ramboll has assumed to be accurate, complete, reliable, and current. Therefore, while Ramboll has utilized its best efforts in preparing this Report, Ramboll does not warrant or guarantee the conclusions set forth in this Report which are dependent or based upon data, information, or statements supplied by third parties or the client. This Report is intended for the Client’s sole and exclusive use and is not for the benefit of any third party and may not be distributed to, disclosed in any form to, used by, or relied upon by, any third party, except as agreed between the Parties, without prior written consent of Ramboll, which consent may be withheld in its sole discretion. Use of this Report or any information contained herein, if by any party other than the Client, shall be at the sole risk of such party and shall constitute a release and agreement by such party to defend and indemnify Ramboll and its officers, employees from and against any liability for direct, indirect, incidental, consequential or special loss or damage or other liability of any nature arising from its use of the Report or reliance upon any of its content. -

Chittaurgarh, Rajasthan

DISTRICT GROUNDWATER BROCHURE CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD Ministry of Water Resources Government of India Western Region Jaipur October, 2007 DISTRICT AT A GLANCE – CHITTAURGARH, RAJASTHAN S Item Statistics No 1 GENERAL INFORMATION (i) Geographical area (sq km) 10,856 (ii) Administrative Division (As on 31.3.2007) Number of Tehsils 13 Number of Blocks 14 Number of Villages 2415 (iii) Population (As per 2001 Census) 18,03,524 (iv) Average Annual Rainfall (1977-2006) in mm 762.7 2 GEOMORPHOLOGY Major Physiographic Units Pediment, Buried Pediment, Intermontane Valley Major Drainage Banas, Gambhiri, Berach, Jakham, Wagon 3 LAND USE (sq km) (a) Forest Area 2800.90 (b) Net Sown Area 4110.00 (c) Cultivable Area 8960.41 4 MAJOR SOIL TYPE Yellow brown soil, Black, soil, Red Loam 5 AREA UNDER PRINCIPAL CROPS (As on 2005) Crops Area in ha Maize 174714 Oil Seeds 168835 Pulses 67720 Wheat 65010 Jowar 21742 Barley 2599 Sugarcane 786 Chilies 627 Bajra 41 6 IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES Source No of Area in ha structure Dug wells 111546 107077 Tube wells/Bore wells 13882 Tanks/Ponds 141 3557 Canals - 3351 Other Sources - 2571 Net Irrigated Area (ha) 116556 Gross Irrigated Area (ha) 126750 ii 7 NUMBER OF GROUND WATER MONITORING WELLS OF CGWB (As on May 2007) Number of Dug wells 31 Number of Piezometers 8 8 PREDOMINANT GEOLOGICAL FORMATIONS Gneiss (Bhilwara Supergroup), Shale, Schist /phyllite (Aravalli Supergroup), Basalt, Limestone & Sandstone (Vindhyan Supergroup) 9 HYDROGEOLOGY Major Water bearing formation Limestone, Gneiss, Basalt, Schist/phyllite -

Secretariat of the State Level Expert Appraisal Committee Rajasthan

Secretariat of the State Level Expert Appraisal Committee Rajasthan, Constituted under the Environmental (Protection) Act, 1986 4, Jhalana, Institutional Area, Jaipur-302004 (Ph.: 0141- 2716810; [email protected]) F.1 (153)/SEAC (4)/ Meeting Notice/Mines/2020/1872-949 Date:08.02.2021 M/s --------- As per Annexure -A Subject: Meeting Notice for the 4.73rd Meeting of the State Level Expert Appraisal Committee (SEAC), (Raj.), scheduled to be held on 23rd ,24th and 25th February,2021. Sir, The 4.73rd Meeting of SEAC is scheduled to be held on 23rd ,24th and 25th February,2021 at 10:30 AM through Video Confrencing as per programme (Annex-A). All the project proponents (PPs) are advised to send an identical set of project documents namely, Form-1, Form-2, Pre-Feasibility Report and / or EIA/EMP Report, supporting documents (as per relevant OMs, circulars, notifications of MoEF & CC updated till date ) and as submitted to the Member Secretary, Secretary, SEAC, Rajasthan, to the Members of SEAC (Annex-B) as per the EIA Notification 2006 and its amendments issued from time to time (in a pen drive) as soft copy as per Ministry of Environment & Forest Order No. J-11013/19/2012-IAII (I) dated 20th March, 2012 as updated /amended) by 14.02.2021along with a hard copy of the computer presentation. Copy of reply to quarries (in hard copy) raised by this office (if any) and point wise reply/information submitted /prepared by P.P is also to be incorporated in tabular / chart form in the documents to be sent to this office and to all the members. -

AGRICULTURE 1. Introduction

AGRICULTURE 1. Introduction : The state occupies 10 percent of the total geographical area of the country, but the vast geographical area commands only 1 percent of the total water resources in the country. Agriculture is mainly rain fed but it is inadequate and aberrant. The dismal scenario of water availability in the state is compounded further by the following factors: Monsoon period is short with late onset and early withdrawal Average rainfall is 58 CMs while 61 percent of the area lies in arid and semi-arid tract. Soil in the area has poor fertility, low water holding capacity and high infiltration rate. A large tract of land is saline and alkaline soil. The south east and eastern part of Aravali range is productive for agriculture purposes having clay loam soil type. Focus of cropping pattern in rain fed areas is to meet the food requirement of the people and fodder requirement of the animals. The crops are grown under high risk. In normal years, farmers face price fall due to glut in the market while drought years have yield risk due to total or partial failure of crops. 2. Land Use Pattern And Land Holdings : Out of the total geographical area in the State, even 50 percent is not cultivable and within cultivable land, soil fertility varies considerably across districts. The wide differences in land productivity indicate the variation in soil health across districts in the State. A relatively large average size of holdings of 3.07 hectare of land is again a manifestation of the less fertile land and soil structure in most of the arid and semi-arid zones in the state. -

And State Agriculture Infrastructure Development Plan (SAIDP) Under RKVY-RAFTAAR 14Th Financial Commission (2017-18 to 2019-20)

Government of Rajasthan State Agriculture Plan (SAP) And State Agriculture Infrastructure Development Plan (SAIDP) under RKVY-RAFTAAR 14th Financial Commission (2017-18 to 2019-20) RAJASTHAN STATE State Agriculture Plan (SAP) and State Agriculture Infrastructure Development Plan (SAIDP)- RAJASTHAN STATE State Agriculture Plan (SAP) And State Agriculture Infrastructure Development Plan (SAIDP) under RKVY-RAFTAAR 14th Financial Commission (2017-18 to 2019-20) RAJASTHAN STATE Prepared by NABARD Consultancy Services (NABCONS) Pvt. Ltd. for the Commissionerate of Agriculture, Government of Rajasthan, Jaipur Department of Agriculture, NABARD Consultancy Services Govt. of Rajasthan Pvt. Ltd. State Agriculture Plan (SAP) and State Agriculture Infrastructure Development Plan (SAIDP)- RAJASTHAN STATE Acknowldgements At the outset we express our sincere thanks to Shri Pawan Kumar Goyal IAS, Additional Chief Secretary to Govt, Agriculture, Government of Rajasthan and Shri Vikas Sitaramji Bhale IAS , Commissioner Agriculture, Government of Rajasthan for giving us opportunity to prepare the prestigious State Agriculture Plan (SAP) and State Agricultre Infrastructure Development Plan (SAIDP). We also gratefully acknowledge the valuable suggestions received to improve the document from Shri Suresh Gautam, Additional Director Research and the members of the Committee headed by him. NABCONS team is also thankful to Shri J.S. Sandhu, Joint Director- RKVY, Shri K.B. Sharma, Joint Director- Planning, Shri Hirendra Sharma, Deputy Director- RKVY, Dr. Poonam Chaudhary, Assistant Director- RKVY and Smt. Khushboo Arya, Agriculture Officer- RKVY for their vauable suggestion and guidance. We are thankful to each and every person of RKVY Cell, Commissionerate of Agriculture, Pant Krishi bhavan, Jaipur. We are thankful to the officials of stakeholder departments who cooperated with us providing deep insight into the developmental agenda, data, information etc. -

IEE: India: Baran Water Supply, Rajasthan Urban Sector

Initial Environmental Examination January 2011 IND: Rajasthan Urban Sector Development Investment Program—Baran Water Supply Prepared by Local Self Government Department of the Government of Rajasthan for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 15 September 2011) Currency unit – Rupee (INR) INR1.00 = $0.02098 $1.00 = INR 47.65 ABBREVIATIONS ADB — Asian Development Bank BOQ — Bill of quantity BMB --- Baran Municipal Board CBO — Community-based organization CFE — Consent for Establishment CFO — Consent for Operation CGWB — Central Ground Water Board CLC — City Level Committees CLIP — City Level Investment Plan CWR — Clear water reservoirs DSC — Design and Supervision Consultants EAC — Expert Appraisal Committee EARF — Environmental Assessment Resettlement Framework EIA — Environmental Impact Assessment EMP — Environmental Management Plan EMS — Environmental Monitoring Specialist EPA — Environmental Protection Agency GLR — Ground level reservoir GRC — Grievance Redress Committee H and S — Health and safety IEE — Initial Environmental Examination IPIU — Investment Program Implementation Unit IPMC — Investment Program Management Consultants IPMU — Investment Program Project Management Unit ITI — Industrial training institutes JNNURM — Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission LSGD — Local Self Government Department MFF — Multitranche financing facility MLD — Million liters per day MOEF — National Ministry of Environment and Forests NAAQS — National Ambient Air Quality Standards NGO — Nongovernmental organization NRRP