Distance Minimizing Paths on Certain Simple Flat Surfaces with Singularities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brief Information on the Surfaces Not Included in the Basic Content of the Encyclopedia

Brief Information on the Surfaces Not Included in the Basic Content of the Encyclopedia Brief information on some classes of the surfaces which cylinders, cones and ortoid ruled surfaces with a constant were not picked out into the special section in the encyclo- distribution parameter possess this property. Other properties pedia is presented at the part “Surfaces”, where rather known of these surfaces are considered as well. groups of the surfaces are given. It is known, that the Plücker conoid carries two-para- At this section, the less known surfaces are noted. For metrical family of ellipses. The straight lines, perpendicular some reason or other, the authors could not look through to the planes of these ellipses and passing through their some primary sources and that is why these surfaces were centers, form the right congruence which is an algebraic not included in the basic contents of the encyclopedia. In the congruence of the4th order of the 2nd class. This congru- basis contents of the book, the authors did not include the ence attracted attention of D. Palman [8] who studied its surfaces that are very interesting with mathematical point of properties. Taking into account, that on the Plücker conoid, view but having pure cognitive interest and imagined with ∞2 of conic cross-sections are disposed, O. Bottema [9] difficultly in real engineering and architectural structures. examined the congruence of the normals to the planes of Non-orientable surfaces may be represented as kinematics these conic cross-sections passed through their centers and surfaces with ruled or curvilinear generatrixes and may be prescribed a number of the properties of a congruence of given on a picture. -

Around and Around ______

Andrew Glassner’s Notebook http://www.glassner.com Around and around ________________________________ Andrew verybody loves making pictures with a Spirograph. The result is a pretty, swirly design, like the pictures Glassner EThis wonderful toy was introduced in 1966 by Kenner in Figure 1. Products and is now manufactured and sold by Hasbro. I got to thinking about this toy recently, and wondered The basic idea is simplicity itself. The box contains what might happen if we used other shapes for the a collection of plastic gears of different sizes. Every pieces, rather than circles. I wrote a program that pro- gear has several holes drilled into it, each big enough duces Spirograph-like patterns using shapes built out of to accommodate a pen tip. The box also contains some Bezier curves. I’ll describe that later on, but let’s start by rings that have gear teeth on both their inner and looking at traditional Spirograph patterns. outer edges. To make a picture, you select a gear and set it snugly against one of the rings (either inside or Roulettes outside) so that the teeth are engaged. Put a pen into Spirograph produces planar curves that are known as one of the holes, and start going around and around. roulettes. A roulette is defined by Lawrence this way: “If a curve C1 rolls, without slipping, along another fixed curve C2, any fixed point P attached to C1 describes a roulette” (see the “Further Reading” sidebar for this and other references). The word trochoid is a synonym for roulette. From here on, I’ll refer to C1 as the wheel and C2 as 1 Several the frame, even when the shapes Spirograph- aren’t circular. -

A Tale of the Cycloid in Four Acts

A Tale of the Cycloid In Four Acts Carlo Margio Figure 1: A point on a wheel tracing a cycloid, from a work by Pascal in 16589. Introduction In the words of Mersenne, a cycloid is “the curve traced in space by a point on a carriage wheel as it revolves, moving forward on the street surface.” 1 This deceptively simple curve has a large number of remarkable and unique properties from an integral ratio of its length to the radius of the generating circle, and an integral ratio of its enclosed area to the area of the generating circle, as can be proven using geometry or basic calculus, to the advanced and unique tautochrone and brachistochrone properties, that are best shown using the calculus of variations. Thrown in to this assortment, a cycloid is the only curve that is its own involute. Study of the cycloid can reinforce the curriculum concepts of curve parameterisation, length of a curve, and the area under a parametric curve. Being mechanically generated, the cycloid also lends itself to practical demonstrations that help visualise these abstract concepts. The history of the curve is as enthralling as the mathematics, and involves many of the great European mathematicians of the seventeenth century (See Appendix I “Mathematicians and Timeline”). Introducing the cycloid through the persons involved in its discovery, and the struggles they underwent to get credit for their insights, not only gives sequence and order to the cycloid’s properties and shows which properties required advances in mathematics, but it also gives a human face to the mathematicians involved and makes them seem less remote, despite their, at times, seemingly superhuman discoveries. -

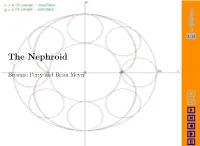

The Nephroid

1/13 The Nephroid Breanne Perry and Brian Meyer Introduction:Definitions Cycloid:The locus of a point on the outside of a circle with a set radius (r) rolling along a straight line. 2/13 Epicycloid:An epicycloid is a cycloid rolling along the outside of a circle instead of along a straight line. The description of an epicycloid depends on the radius of the circle being traversed (b) and the radius of the rolling circle (a). Nephroid:A bicuspid epicycloid. Nephroid Literally means ”kidney shaped”. The nephroid arises when the radius of the center circle is twice that of the rolling circle (b=a/2). Catacaustic:The curve formed by reflecting light off of another curve. Catacaustic of the Cardiod 3/13 History of the Nephroid The Nephroid was first studied by Christiaan Huygens and Tshirn- hausen in 1678, they found it to be the catacaustic of a circle when the 4/13 light source is at infinity. George Airy proved this to be true through the wave theory of light in 1838. In 1878 Richard Proctor coined the term nephroid in his book The Geometry of cycloids. The term Nephroid replaced the existing two-cusped epicycloid. Some members of the epicycloid family 5/13 line 2 b=a Cardioid line 3 b=a/2 Nephroid line 4 b=a/3 three cusped epicycloid Deriving the formula for the Nephroid First to determine the relationship between the change in angle from the large circle to the small circle, we analyze the the relationship be- 6/13 tween point D and E as they traverse the outside of their respected circles. -

Engineering Curves and Theory of Projections

ME 111: Engineering Drawing Lecture 4 08-08-2011 Engineering Curves and Theory of Projection Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati Guwahati – 781039 Distance of the point from the focus Eccentrici ty = Distance of the point from the directric When eccentricity < 1 Ellipse =1 Parabola > 1 Hyperbola eg. when e=1/2, the curve is an Ellipse, when e=1, it is a parabola and when e=2, it is a hyperbola. 2 Focus-Directrix or Eccentricity Method Given : the distance of focus from the directrix and eccentricity Example : Draw an ellipse if the distance of focus from the directrix is 70 mm and the eccentricity is 3/4. 1. Draw the directrix AB and axis CC’ 2. Mark F on CC’ such that CF = 70 mm. 3. Divide CF into 7 equal parts and mark V at the fourth division from C. Now, e = FV/ CV = 3/4. 4. At V, erect a perpendicular VB = VF. Join CB. Through F, draw a line at 45° to meet CB produced at D. Through D, drop a perpendicular DV’ on CC’. Mark O at the midpoint of V– V’. 3 Focus-Directrix or Eccentricity Method ( Continued) 5. With F as a centre and radius = 1–1’, cut two arcs on the perpendicular through 1 to locate P1 and P1’. Similarly, with F as centre and radii = 2– 2’, 3–3’, etc., cut arcs on the corresponding perpendiculars to locate P2 and P2’, P3 and P3’, etc. Also, cut similar arcs on the perpendicular through O to locate V1 and V1’. 6. Draw a smooth closed curve passing through V, P1, P/2, P/3, …, V1, …, V’, …, V1’, … P/3’, P/2’, P1’. -

The Mechanical Drawing of Cycloids, the Geometric Chuck

The Mechanical Drawing of Cycloids, The Geometric Chuck Robert Craig 8633 E. 96th Terrace Kansas City, MO 64134 E-mail [email protected] Abstract This paper discusses cycloids and their construction using the 19th century mechanical drawing instrument known as the Geometric Chuck. The first part of the paper is a brief history and description of the Geometric Chuck. The last part of the paper is devoted to a discussion the definition of cycloids and examples showing the results that various settings of the Geometric Chuck have on the cycloid patterns produced. This paper is an attempt, in part, to respond to the comment in the Savory book "As this book does not aim at giving a scientific account of the principles on which it works. It might be an exceedingly interesting subject for the scientific person, ….the scientific knowledge required to understand a three-part chuck would be so great that I doubt if there is the person existing who could describe the course of a line that would be produced…."[6] 1. History 1.1 Definition. "The Geometric Chuck is an arrangement of mechanism for producing two or more circular movements in parallel planes. The combination of these movements with different velocity ratios and different radii results in the formation of a great variety of highly interesting curves and geometric figures"[1]. The Geometric Chuck is just one of many devices that were designed to be used as accessories to the Rose Engine Lathe. This lathe, similar to the modern lathe in name only, was designed to produce ornately decorated items. -

Hermite Interpolation with HE-Splines Miroslav L´Aviˇcka, Zbynˇek S´Irˇ and Bohum´Ir Bastl Dept

Geometry and Graphics 2009 205 Hermite interpolation with HE-splines Miroslav L´aviˇcka, Zbynˇek S´ırˇ and Bohum´ır Bastl Dept. of Mathematics, Fac. of Applied Sciences, Univ. of West Bohemia Univerzitn´ı22, 301 00 Plzeˇn, Czech Republic lavicka,zsir,bastl @kma.zcu.cz { } Abstract. Hypo/epicycloids (shortly HE-cycloids) are well-known curves, in detail studied in classical geometry. Hence, one may wonder what new can be said about these traditional geometric objects. It has been proved recently, cf. [12], that all rational HE-cycloids are curves with rational offsets, i.e. they belong to the class of rational Pythagorean hodograph curves. In this paper, we present an algorithm for G1 Hermite interpolation with hypo/epicycloidal arcs which results from their support function representation. Keywords: Hypocycloids; epicycloids; Pythagorean hodograph curves; rational offsets; support function; Hermite interpolation 1 Introduction Hypocycloids and epicycloids are a subclass of the so called roulettes, i.e., planar curves traced by a fixed point on a closed convex curve as that curve rolls without slipping along a second curve. In this case, both curves are circles, cf. [13, 1, 9]. Various sizes of circles generate different hypo/epicycloids, which are closed when the ratio of the radius of the rolling circle and the radius of the other circle is rational. It has been proved recently, cf. [12], that all rational hypo/epicycloids are curves with Pythagorean normals and therefore they provide ratio- nal offsets. This new result was obtained with the help of support function (SF) representation of hypo/epicycloids. In this paper, we present the main idea of the algorithm for G1 Hermite interpolation with hypo/epicycloidal arcs. -

Representations of Epitrochoids and Hypotrochoids

REPRESENTATIONS OF EPITROCHOIDS AND HYPOTROCHOIDS by Michelle Natalie Rene Marie Bouthillier Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia March 2018 © Copyright by Michelle Natalie Rene Marie Bouthillier, 2018 Table of Contents List of Figures ..................................... iii Abstract ......................................... iv Acknowledgements .................................. v Chapter 1 Introduction ............................. 1 Chapter 2 The Implicitization Problem .................. 5 2.1 Introduction . 5 2.2 Resultants . 9 2.3 Gr¨obnerBases . 18 2.4 Resultants versus Gr¨obnerBasis . 47 Chapter 3 Implicitization of Hypotrochoids and Epitrochoids ... 51 3.1 Implicitization Method . 51 3.2 Results for Small Values of m and n . 56 3.3 Examples . 64 Chapter 4 Envelopes ............................... 79 4.1 Introduction . 79 4.2 Epicycloids . 80 4.3 Hypocycloids . 87 Chapter 5 Conclusion .............................. 94 Bibliography ....................................... 95 Appendix ......................................... 97 ii List of Figures 1.1 Epitrochoid with R = 1, r = 3, d = 4. 1 1.2 Hypotrochoid with R = 4, r = 1, d = 3~2. 2 1.3 A trochoid with a = 2r ........................ 3 2.1 Example of a curve that we may wish to implicitize . 8 3.1 Epicycloids with implicit forms described by Conjecture 2 . 66 3.2 Epicycloids with implicit forms described by Conjecture 3 . 67 3.3 Hypocycloids with implicit forms described by Conjecture 4 . 69 3.4 Hypocycloids with implicit forms described by Conjecture 5 . 71 3.5 Hypocycloids with implicit forms described by Conjecture 6 . 73 3.6 Hypocycloids with implicit forms described by Conjecture 7 . 74 3.7 Hypocycloids with implicit forms described by Conjecture 8 . 76 3.8 Hypocycloids with implicit forms described by Conjecture 9 . -

Closed Cycloids in a Normed Plane

Closed Cycloids in a Normed Plane Marcos Craizer, Ralph Teixeira and Vitor Balestro Abstract. Given a normed plane P, we call P-cycloids the planar curves which are homothetic to their double P-evolutes. It turns out that the radius of curvature and the support function of a P-cycloid satisfy a differential equation of Sturm-Liouville type. By studying this equation we can describe all closed hypocycloids and epicycloids with a given number of cusps. We can also find an orthonormal basis of C0(S1) with a natural decomposition into symmetric and anti-symmetric functions, which are support functions of symmetric and constant width curves, respectively. As applications, we prove that the iterations of involutes of a closed curve converge to a constant and a generalization of the Sturm-Hurwitz Theorem. We also prove versions of the four vertices theorem for closed curves and six vertices theorem for closed constant width curves. Mathematics Subject Classification (2010). 52A10, 52A21, 53A15, 53A40. Keywords. Minkowski Geometry, Sturm-Liouville equations, evolutes, hypocycloids, curves of constant width, Sturm-Hurwitz theorem, Four vertices theorem, Six vertices theorem. arXiv:1608.01651v2 [math.DG] 2 Feb 2017 1. Introduction Euclidean cycloids are planar curves homothetic to their double evolutes. When the ratio of homothety is λ > 1, they are called hypocycloids, and when 0 <λ< 1, they are called epicycloids. In a normed plane, or Minkowski plane ([8, 9, 10, 14]), there exists a natural way to define the double evolute of a locally convex curve ([3]). Cycloids with respect to a normed plane P are curves homothetic to their double P-evolutes. -

Exploring Cycloids …

Using Geometer’s Sketchpad to Support Mathematical Thinking Exploring Cycloids … The cycloid is the locus of a point on the rim of a circle of radius a rolling along a straight line. It was studied and named by Galileo in 1599. Eric W. Weisstein. "Cycloid." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Cycloid.html € A curtate cycloid, sometimes also called a contracted cycloid, is the path traced out by a fixed point at a radius b < a, where a is the radius of a rolling circle. Curtate cycloids are used by some violin makers for the back arches of some instruments, and they resemble those found in some of the great Cremonese instruments of the early 18th century, such as those by Stradivari. € Eric W. Weisstein. "Curtate Cycloid."€ From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/CurtateCycloid.html The prolate cycloid is the path traced out by a fixed point at a radius b > a, where a is the radius of a rolling circle, also sometimes called an extended cycloid. The prolate cycloid contains loops. Eric W. Weisstein. "Prolate Cycloid." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. € http://mathworld.wolfram.com/ProlateCycloid.html € Shelly Berman p. 1 of 4 Jo Ann Fricker Cycloids.doc Using Geometer’s Sketchpad to Support Mathematical Thinking Adpated from Algebra in Motion by Audrey Weeks http://www.calculusinmotion.com Want More? CYCLOIDS Show Epi/Hypocycloid (c)AWeeks1/03 www.calculusinmotion.com At any time, ESC erases traces. For wheel size, drag W ⇒ W wheel radius = 46.000 pixels For pebble size, drag P ⇒ P 1 rev. -

Collected Atos

Mathematical Documentation of the objects realized in the visualization program 3D-XplorMath Select the Table Of Contents (TOC) of the desired kind of objects: Table Of Contents of Planar Curves Table Of Contents of Space Curves Surface Organisation Go To Platonics Table of Contents of Conformal Maps Table Of Contents of Fractals ODEs Table Of Contents of Lattice Models Table Of Contents of Soliton Traveling Waves Shepard Tones Homepage of 3D-XPlorMath (3DXM): http://3d-xplormath.org/ Tutorial movies for using 3DXM: http://3d-xplormath.org/Movies/index.html Version November 29, 2020 The Surfaces Are Organized According To their Construction Surfaces may appear under several headings: The Catenoid is an explicitly parametrized, minimal sur- face of revolution. Go To Page 1 Curvature Properties of Surfaces Surfaces of Revolution The Unduloid, a Surface of Constant Mean Curvature Sphere, with Stereographic and Archimedes' Projections TOC of Explicitly Parametrized and Implicit Surfaces Menu of Nonorientable Surfaces in previous collection Menu of Implicit Surfaces in previous collection TOC of Spherical Surfaces (K = 1) TOC of Pseudospherical Surfaces (K = −1) TOC of Minimal Surfaces (H = 0) Ward Solitons Anand-Ward Solitons Voxel Clouds of Electron Densities of Hydrogen Go To Page 1 Planar Curves Go To Page 1 (Click the Names) Circle Ellipse Parabola Hyperbola Conic Sections Kepler Orbits, explaining 1=r-Potential Nephroid of Freeth Sine Curve Pendulum ODE Function Lissajous Plane Curve Catenary Convex Curves from Support Function Tractrix -

New Insight Into Cycloidal Areas

New Insight into Cycloidal Areas Tom M. Apostol and Mamikon A. Mnatsakanian doi:10.4169/193009709X458573 1. INTRODUCTION. A cycloid is the path traced by a point on the boundary of a circular disk that rolls without slipping along a straight line. It forms a sequence of arches resting on the line, as shown in Figure 1. It is known that the area of the shaded region below one arch is three times the area of the rolling disk. Our analysis shows that the factor 3 reflects a much deeper property of cycloidal sectors. Figure 2 shows various stages of rotation of the disk, together with cycloidal sector OPC bounded by arc OP and two line segments OC and PC. At each stage we have: Figure 1. Cycloidal arch has area three times that of the rolling disk. P P C C O O P P O C O C Figure 2. Each cycloidal sector OPC has area three times that of the shaded segment of the rolling disk cut by chord PC, where C is the contact point of the disk and base line. Theorem 1. Cycloidal sector OPC has area three times that of the overlapping circu- lar segment cut from the rolling disk by chord PC. This remarkable geometric property follows easily from an elegant area relation il- lustrated in Figure 3. The rolling disk is tangent to the upper and lower boundaries of the rectangle circumscribing the cycloid, at corresponding points of tangency T and C. Diameter TC divides the rolling circle into two semicircles, one of which intersects the cycloid at point P as indicated.