Eyewitness Identification Issues at the Inter- United States, Accounting for More Wrongful Convic- Section of the Two Fields

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

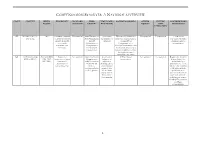

Compensation Chart by State

Updated 5/21/18 NQ COMPENSATION STATUTES: A NATIONAL OVERVIEW STATE STATUTE WHEN ELIGIBILITY STANDARD WHO TIME LIMITS MAXIMUM AWARDS OTHER FUTURE CONTRIBUTORY PASSED OF PROOF DECIDES FOR FILING AWARDS CIVIL PROVISIONS LITIGATION AL Ala.Code 1975 § 29-2- 2001 Conviction vacated Not specified State Division of 2 years after Minimum of $50,000 for Not specified Not specified A new felony 150, et seq. or reversed and the Risk Management exoneration or each year of incarceration, conviction will end a charges dismissed and the dismissal Committee on claimant’s right to on grounds Committee on Compensation for compensation consistent with Compensation Wrongful Incarceration can innocence for Wrongful recommend discretionary Incarceration amount in addition to base, but legislature must appropriate any funds CA Cal Penal Code §§ Amended 2000; Pardon for Not specified California Victim 2 years after $140 per day of The Department Not specified Requires the board to 4900 to 4906; § 2006; 2009; innocence or being Compensation judgment of incarceration of Corrections deny a claim if the 2013; 2015; “innocent”; and Government acquittal or and Rehabilitation board finds by a 2017 declaration of Claims Board discharge given, shall assist a preponderance of the factual innocence makes a or after pardon person who is evidence that a claimant recommendation granted, after exonerated as to a pled guilty with the to the legislature release from conviction for specific intent to imprisonment, which he or she is protect another from from release serving a state prosecution for the from custody prison sentence at underlying conviction the time of for which the claimant exoneration with is seeking transitional compensation. -

Pleadings: Appeal and Error. an Appellate Court

Nebraska Supreme Court Online Library www.nebraska.gov/apps-courts-epub/ 09/28/2021 08:15 PM CDT - 329 - NEBRASKA SUPREME COURT ADVAncE SHEETS 298 NEBRASKA REPORTS NADEEM V. STATE Cite as 298 Neb. 329 MOHAMMED NADEEM, APPELLANT, V. STATE OF NEBRASKA, APPELLEE. ___ N.W.2d ___ Filed December 8, 2017. No. S-16-113. 1. Motions to Dismiss: Pleadings: Appeal and Error. An appellate court reviews a district court’s order granting a motion to dismiss de novo, accepting all allegations in the complaint as true and drawing all reason- able inferences in favor of the nonmoving party. 2. Motions to Dismiss: Pleadings. For purposes of a motion to dismiss, a court may consider some materials that are part of the public record or do not contradict the complaint, as well as materials that are necessarily embraced by the pleadings. 3. Pleadings: Complaints. Documents embraced by the pleadings are materials alleged in a complaint and whose authenticity no party ques- tions, but which are not physically attached to the pleadings. 4. ____: ____. Documents embraced by the complaint are not considered matters outside the pleadings. 5. Res Judicata: Judgments. Res judicata bars relitigation of any right, fact, or matter directly addressed or necessarily included in a former adjudication if (1) the former judgment was rendered by a court of com- petent jurisdiction, (2) the former judgment was a final judgment, (3) the former judgment was on the merits, and (4) the same parties or their privies were involved in both actions. 6. Convictions: Claims: Pleadings. Under Neb. Rev. -

The Myth of the Presumption of Innocence

Texas Law Review See Also Volume 94 Response The Myth of the Presumption of Innocence Brandon L. Garrett* I. Introduction Do we have a presumption of innocence in this country? Of course we do. After all, we instruct criminal juries on it, often during jury selection, and then at the outset of the case and during final instructions before deliberations. Take this example, delivered by a judge at a criminal trial in Illinois: "Under the law, the Defendant is presumed to be innocent of the charges against him. This presumption remains with the Defendant throughout the case and is not overcome until in your deliberations you are convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that the Defendant is guilty."' Perhaps the presumption also reflects something more even, a larger commitment enshrined in a range of due process and other constitutional rulings designed to protect against wrongful convictions. The defense lawyer in the same trial quoted above said in his closings: [A]s [the defendant] sits here right now, he is presumed innocent of these charges. That is the corner stone of our system of justice. The best system in the world. That is a presumption that remains with him unless and until the State can prove him guilty beyond2 a reasonable doubt. That's the lynchpin in the system ofjustice. Our constitutional criminal procedure is animated by that commitment, * Justice Thurgood Marshall Distinguished Professor of Law, University of Virginia School of Law. 1. Transcript of Record at 13, People v. Gonzalez, No. 94 CF 1365 (Ill.Cir. Ct. June 12, 1995). 2. -

Actual Innocence in New York: the Curious Case of People V

ACTUAL INNOCENCE IN NEW YORK: THE CURIOUS CASE OF PEOPLE V. HAMILTON Benjamin E. Rosenberg* It is rare for a case from the New York Appellate Division to be as significant as People v. Hamilton.1 The case, however, was the first New York appellate court decision to hold that a defendant might vacate his conviction if he could demonstrate that he was “actually innocent” of the crime of which he was charged. Although the precedential force of the decision is limited to the Second Department, trial courts throughout the state are required to follow Hamilton unless or until the appellate court in their own Department rules on the issue.2 Courts throughout the state are thus entertaining numerous “actual innocence” motions inspired by Hamilton. While courts in some other states, including state appellate courts, have recognized actual innocence claims,3 whether such claims should be recognized, and if so under what circumstances, is a very live issue in the federal courts and numerous state courts throughout the country. Examination of Hamilton, therefore, provides a useful way to consider issues that are of surpassing importance in criminal law and that will likely reoccur in cases throughout the country. As Hamilton goes further than many other courts have in considering the implications of actual innocence claims, consideration of Hamilton may be of considerable value to courts that consider actual innocence claims. Hamilton is a trailblazer, and its trail will repay careful study. I. BACKGROUND Before considering Hamilton itself, it is appropriate to consider briefly both New York’s collateral relief statute and the types of “actual innocence” claims that might be asserted. -

Wrongful Convictions After a Century of Research Jon B

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Northwestern University Illinois, School of Law: Scholarly Commons Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 100 Article 7 Issue 3 Summer Summer 2010 One Hundred Years Later: Wrongful Convictions after a Century of Research Jon B. Gould Richard A. Leo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Jon B. Gould, Richard A. Leo, One Hundred Years Later: Wrongful Convictions after a Century of Research, 100 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 825 (2010) This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/10/10003-0825 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 100, No. 3 Copyright © 2010 by Jon B. Gould & Richard A. Leo Printed in U.S.A. II. “JUSTICE” IN ACTION ONE HUNDRED YEARS LATER: WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS AFTER A CENTURY OF RESEARCH JON B. GOULD* & RICHARD A. LEO** In this Article, the authors analyze a century of research on the causes and consequences of wrongful convictions in the American criminal justice system while explaining the many lessons of this body of work. This Article chronicles the range of research that has been conducted on wrongful convictions; examines the common sources of error in the criminal justice system and their effects; suggests where additional research and attention are needed; and discusses methodological strategies for improving the quality of research on wrongful convictions. -

Senate Bill 14: Fixing Maryland's Exoneree Compensation

Contact: Michelle Feldman, State Campaigns Director, (516) 557-6650 [email protected] Senate Bill 14: Fixing Maryland’s Exoneree Compensation Law Problems w/Current Law Maryland is one of 35 states with an exoneree compensation. However, the law is not working effectively. Problems include: 1. Unfair eligibility criteria exclude some exonerees. • Eligibility limited to exonerees who receive 1) governor’s pardon or 2) prosecutor-approved writ of actual innocence (WOIA). However, WOIA is just one of several laws that can exonerate an innocent person in Maryland. • Exonerees are ineligible for compensation if their convictions were overturned based on: DNA testing, constitutional violations (e.g. defense failed to present evidence), WOIA opposed by prosecutor. 2. No set amount, process or timelines for payment. • BPW is not required to pay compensation at all, it is discretionary. • BPW decides how much & when to pay. • BPW’s primary role of funding capital projects; exoneree compensation is not its area of expertise. 3. Allows civil & compensation awards. Exonerees can receive state compensation and large civil awards and settlements. Senate Bill 14 1. Eligibility based on proof of innocence. • Based on proof of innocence, rather than law used for overturning conviction. • Must prove to Administrative Law Judge (ALJ), by clear and convincing evidence, that the person did not commit the crime for which he or she was incarcerated. 2. Consistent process. ALJ determines if applicant is eligible and orders BPW to make payments and agencies to provide social services. National Picture: 22 states have courts determine eligibility for exoneree compensation. 3. Sets amount and timeline for payment. -

Eyewitness Report.Qxd:Layout 3

REEVALUATING LINEUPS: WHY WITNESSES MAKE MISTAKES AND HOW TO REDUCE THE CHANCE OF A MISIDENTIFICATION AN INNOCENCE PROJECT REPORT BENJAMIN N. CARDOZO SCHOOL OF LAW, YESHIVA UNIVERSITY BOARD OF DIRECTORS Gordon DuGan President and Chief Executive Officer, W.P. Carey & Co., LLC Senator Rodney Ellis Texas State Senate, District 13 Board Chair Jason Flom President, LAVA Records John Grisham Author CONTENTS Calvin Johnson Former Innocence Project client and exoneree; 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................................................3 Supervisor, Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority Dr. Eric S. Lander 2. HISTORY AND OVERVIEW OF EYEWITNESS MISIDENTIFICATION ..................................6 Director, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard Professor of Biology, MIT Hon. Janet Reno 3. PROBLEMS WITH TRADITIONAL EYEWITNESS IDENTIFICATION PROCEDURES.............10 Former U.S. Attorney General Matthew Rothman 4. HOW TO PREVENT MISIDENTIFICATION.....................................................................16 Managing Director and Global Head of Quantitative Equity Strategies, Barclays Capital 5. REFORMS AT WORK..................................................................................................22 Stephen Schulte Founding Partner and Of Counsel, Schulte Roth & Zabel, LLP ENDNOTES.....................................................................................................................26 Bonnie Steingart Partner, Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson LLP APPENDIX -

Compensation Statutes: a National Overview

COMPENSATION STATUTES: A NATIONAL OVERVIEW STATE STATUTE WHEN ELIGIBILITY STANDARD WHO TIME LIMITS MAXIMUM AWARDS OTHER FUTURE CONTRIBUTORY PASSED OF PROOF DECIDES FOR FILING AWARDS CIVIL PROVISIONS LITIGATION AL Ala.Code 1975 § 29-2- 2001 Conviction vacated Not specified State Division of 2 years after Minimum of $50,000 for Not specified Not specified A new felony 150, et seq. or reversed and the Risk Management exoneration or each year of incarceration, conviction will end a charges dismissed and the dismissal Committee on claimant’s right to on grounds Committee on Compensation for compensation consistent with Compensation Wrongful Incarceration can innocence for Wrongful recommend discretionary Incarceration amount in addition to base, but legislature must appropriate any funds CA Cal Penal Code §§ Amended 2000; Pardon for Not specified California Victim 2 years after $140 per day of Not specified Not specified Requires the board to 4900 to 4906; § 2006; 2009; innocence or being Compensation judgment of incarceration deny a claim if the 2013; 2015 “innocent”; and Government acquittal or board finds by a declaration of Claims Board discharge given, preponderance of the factual innocence makes a or after pardon evidence that a claimant recommendation granted, after pled guilty with the to the legislature release from specific intent to imprisonment, protect another from from release prosecution for the from custody underlying conviction for which the claimant is seeking compensation. 1 2 STATE STATUTE WHEN ELIGIBILITY STANDARD WHO TIME LIMITS MAXIMUM AWARDS OTHER FUTURE CONTRIBUTORY PASSED OF PROOF DECIDES FOR FILING AWARDS CIVIL PROVISIONS LITIGATION CO C.R.S.A. § 13-65-101, 2013 Requires the state Clear and District Court in 2 years after Colorado inmates will On or before Not Specified A claimant cannot be et seq.; compensate a convincing the county in exoneration or receive $70,000 for each September 1, compensated for those person, or the which the case dismissal year wrongfully 2013, the years when he or she immediate family originated. -

The Innocence Checklist

THE INNOCENCE CHECKLIST Carrie Leonetti* ABSTRACT Because true innocence is unknowable, scholars who study wrongful convic- tions and advocates who seek to vindicate the innocent must use proxies for inno- cence. Court processes or of®cial recognition of innocence are the primary proxy for innocence in research databases of exonerees. This Article offers an innova- tive alternative to this process-based proxy: a substantive checklist of factors that indicates a likely wrongful conviction, derived from empirical and jurispru- dential sources. Notably, this checklist does not rely on of®cial recognition of innocence for its objectivity or validity. Instead the checklist aggregates myriad indicators of innocence: factors known to contribute to wrongful convictions; rules of professional conduct; innocence-project intake criteria; prosecutorial conviction-integrity standards; and jurisprudence governing when convictions must be overturned because of fresh evidence or constitutional violations. A checklist based on articulated, uniformly applicable criteria is preferable to the more subjective and less regulated decisionmaking of judges and prosecutors who determine innocence using an of®cial exoneration methodology. Only a con- ception of innocence independent of of®cial exoneration can provide the neces- sary support for reform of barriers to more fruitful postconviction review mechanisms. INTRODUCTION ............................................ 99 I. BACKGROUND: THE INNOCENCE MOVEMENT .................... 100 A. Known Causes of Wrongful -

Is Innocence Irrelevant to AEDPA's Statute of Limitations - Avoiding a Miscarriage of Justice in Federal Habeas Corpus

Volume 56 Issue 1 Article 4 2011 Is Innocence Irrelevant to AEDPA's Statute of Limitations - Avoiding a Miscarriage of Justice in Federal Habeas Corpus Angela Ellis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Angela Ellis, Is Innocence Irrelevant to AEDPA's Statute of Limitations - Avoiding a Miscarriage of Justice in Federal Habeas Corpus, 56 Vill. L. Rev. 129 (2011). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr/vol56/iss1/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Law Review by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Ellis: Is Innocence Irrelevant to AEDPA's Statute of Limitations - Avoid 2011] "IS INNOCENCE IRRELEVANT" TO AEDPA'S STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS? AVOIDING A MISCARRIAGE OF JUSTICE IN FEDERAL HABEAS CORPUS "The meritorious claims are few, but our procedures must ensure that those few claims are not stifled by undiscriminating generalities. The complexities of our federalism ... are not to be escaped by simple, rigid rules which, by avoiding some abuses, generate others." -Justice Felix Frankfurter' I. INTRODUCTION Imagine you are arrested for a crime you did not commit.2 Perhaps you were misidentified by an eyewitness, or accused by an informant who received a deal in exchange for testimony.3 Then imagine that you are convicted in a trial that violates your constitutional rights: maybe the gov- ernment withholds evidence of your innocence or, worse, uses false testi- 1. -

People V. Montes, 2015 IL App (2D) 140485

Illinois Official Reports Appellate Court People v. Montes, 2015 IL App (2d) 140485 Appellate Court THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF ILLINOIS, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. Caption AUGUSTINE T. MONTES, Defendant-Appellant. District & No. Second District Docket No. 2-14-0485 Filed February 6, 2015 Held On appeal from the summary dismissal of defendant’s postconviction (Note: This syllabus petition claiming actual innocence based on entrapment and constitutes no part of the ineffective assistance of counsel arising from defendant’s convictions opinion of the court but in absentia for attempted first-degree murder and aggravated has been prepared by the discharge of a firearm, the appellate court affirmed defendant’s Reporter of Decisions convictions and the summary dismissal of his postconviction petition, for the convenience of since entrapment was not available as a defense where defendant the reader.) denied committing that offense and defendant’s absence from the trial precluded his counsel from meeting his obligation to discuss the availability of a lesser-included-offense instruction with defendant and whether there was a reasonable probability that submission of such an instruction could change the result. Decision Under Appeal from the Circuit Court of Kane County, No. 05-CF-2797; the Review Hon. Robert K. Villa, Judge, presiding. Judgment Affirmed. Counsel on Matthew J. Haiduk, of Geneva, for appellant. Appeal Joseph H. McMahon, State’s Attorney, of St. Charles (Lawrence M. Bauer and Sally A. Swiss, both of State’s Attorneys Appellate Prosecutor’s Office, of counsel), for the People. Panel JUSTICE JORGENSEN delivered the judgment of the court, with opinion. Justices McLaren and Birkett concurred in the judgment and opinion. -

Actual Innocence Writs

ACTUAL INNOCENCE WRITS GARY A. UDASHEN Sorrels, Udashen & Anton 2311 Cedar Springs Road Suite 250 Dallas, Texas 75201 214-468-8100 214-468-8104 fax [email protected] www.sualaw.com State Bar of Texas CRIMINAL WRITS COURSE December 1-2, 2016 Austin, Texas Chapter 9 GARY A. UDASHEN Sorrels, Udashen & Anton 2311 Cedar Springs Road Suite 250 Dallas, Texas 75201 www.sualaw.com 214-468-8100 Fax: 214-468-8104 [email protected] www.sualaw.com BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION EDUCATION B.S. with Honors, The University of Texas at Austin, 1977 J.D., Southern Methodist University, 1980 PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES Innocence Project of Texas, President; State Bar of Texas (Member, Criminal Law Section, Appellate Section); Dallas Bar Association, Chairman Criminal Section; Fellow, Dallas Bar Association; Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association, Board Member, Chairman, Appellate Committee, Legal Specialization Committee, Co-Chairman, Strike Force; National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers; Dallas County Criminal Defense Lawyers Association; Dallas Inn of Courts, LVI; Board Certified, Criminal Law and Criminal Appellate Law, Texas Board of Legal Specialization; Instructor, Trial Tactics, S.M.U. School of Law, 1992, Texas Criminal Justice Integrity Unit, Member; Texas Board of Legal Specialization, Advisory Committee, Criminal Appellate Law PUBLICATIONS, SEMINAR PRESENTATIONS AND HONORS: Features Article Editor, Voice for the Defense, 1993-2000 Author/Speaker: Advanced Criminal Law Course, 1989, 1994, 1995, 2003, 2006, 2009, 2010, 201 2012, 2013, 2016; Course Director 2015 Author/Speaker: Criminal Defense Lawyers Project Seminars, Dallas Bar Association Seminars, Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Seminars, Center for American and International Law Seminars, 1988-2016 Author: Various articles in Voice for the Defense, 1987-2005 Author: S.M.U.