Conservation Perspectives: the GCI Newsletter, Spring 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Archive of Renowned Architectural Photographer

DATE: August 18, 2005 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE GETTY ACQUIRES ARCHIVE OF JULIUS SHULMAN, WHOSE ICONIC PHOTOGRAPHS HELPED TO DEFINE MODERN ARCHITECTURE Acquisition makes the Getty one of the foremost centers for the study of 20th-century architecture through photography LOS ANGELES—The Getty has acquired the archive of internationally renowned architectural photographer Julius Shulman, whose iconic images have helped to define the modern architecture movement in Southern California. The vast archive, which was held by Shulman, has been transferred to the special collections of the Research Library at the Getty Research Institute making the Getty one of the most important centers for the study of 20th-century architecture through the medium of photography. The Julius Shulman archive contains over 260,000 color and black-and-white negatives, prints, and transparencies that date back to the mid-1930s when Shulman began his distinguished career that spanned more than six decades. It includes photographs of celebrated monuments by modern architecture’s top practitioners, such as Richard Neutra, Frank Lloyd Wright, Raphael Soriano, Rudolph Schindler, Charles and Ray Eames, Gregory Ain, John Lautner, A. Quincy Jones, Mies van der Rohe, and Oscar Niemeyer, as well as images of gas stations, shopping malls, storefronts, and apartment buildings. Shulman’s body of work provides a seminal document of the architectural and urban history of Southern California, as well as modernism throughout the United States and internationally. The Getty is planning an exhibition of Shulman’s work to coincide with the photographer’s 95th birthday, which he will celebrate on October 10, 2005. The Shulman photography archive will greatly enhance the Getty Research Institute’s holdings of architecture-related works in its Research Library, which -more- Page 2 contains one of the world’s largest collections devoted to art and architecture. -

Spring 2015 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE

theGETTY A WORLD OF ART, RESEARCH, CONSERVATION, AND PHILANTHROPY | Spring 2015 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE theGETTY Spring 2014 TABLE OF President’s Message 3 by James Cuno President and CEO, the J. Paul Getty Trust CONTENTS New and Noteworthy 4 Earlier this year I attended the World Economic Forum in Keeping it Modern 6 Davos, Switzerland, during which government officials and corporate, education, and cultural leaders gather to explore Darkroom Alchemists Reinvent Photography 14 the economic and political prospects for the coming year. I gave a presentation about the ways in which digital technol- A Sense of Place in the City of Angels 20 ogy is transforming the museum experience—from initial dis- covery, to visiting, to research and collaboration, to the ways Thousands of Rare Books on your Desktop 24 in which visitors can engage more deeply with the collection through digital resources. This issue of The Getty expands Book Excerpt: J. M. W. Turner: Painting Set Free 27 on our previous coverage of how the Getty is “going digital” through projects like the HistoricPlacesLA initiative from the New from Getty Publications 28 Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) and the many digital fac- ets that are accessible to researchers and patrons around the From The Iris 30 world from the Getty Research Institute Library. Last month, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti joined GCI New Acquisition 31 Director Tim Whalen, Foundation Director Deborah Marrow, and me to launch HistoricPlacesLA, the city’s groundbreaking Getty Events 32 new system for mapping and inventorying historic resources in Los Angeles. HistoricPlacesLA contains information gath- Exhibitions 34 ered through SurveyLA—a citywide survey of LA’s significant historic resources—a public/private partnership between the From the Vault 35 City of Los Angeles and the Getty, including both the GCI and Foundation. -

Press Image Sheet

NEWS FROM THE GETTY news.getty.edu | [email protected] DATE: September 17, 2019 MEDIA CONTACT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Julie Jaskol Getty Communications (310) 440-7607 [email protected] GETTY TO DEVOTE $100 MILLION TO ADDRESS THREATS TO THE WORLD’S ANCIENT CULTURAL HERITAGE Global initiative will enlist partners to raise awareness of threats and create effective conservation and education strategies Participants in the 2014 Mosaikon course Conservation and Management of Archaeo- logical Sites with Mosaics conduct a condition survey exercise of the Achilles Mosaic at the Paphos Archeological Park, Paphos, Cyprus. Continued work at Paphos will be undertaken as part of Ancient Worlds Now. Los Angeles – The J. Paul Getty Trust will embark on an unprecedented and ambitious $100- million, decade-long global initiative to promote a greater understanding of the world’s cultural heritage and its universal value to society, including far-reaching education, research, and conservation efforts. The innovative initiative, Ancient Worlds Now: A Future for the Past, will explore the interwoven histories of the ancient worlds through a diverse program of ground-breaking The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 403 Tel: 310 440 7360 www.getty.edu Communications Department Los Angeles, CA 90049-1681 Fax: 310 440 7722 scholarship, exhibitions, conservation, and pre- and post- graduate education, and draw on partnerships across a broad geographic spectrum including Asia, Africa, the Americas, the Middle East, and Europe. “In an age of resurgent populism, sectarian violence, and climate change, the future of the world’s common heritage is at risk,” said James Cuno, president and CEO of the J. -

Julius Shulman: Modernity and the Metropolis (October 11, 2005–January 22, 2006)

RELATED EVENTS Julius Shulman: Modernity and the Metropolis (October 11, 2005–January 22, 2006) RELATED EVENTS AND PUBLICATIONS All events are free but reservations are required. For more information or to make a reservation, please call 310-440-7300 or visit www.getty.edu. CONVERSATION Julius Shulman discusses his work, the exhibition, and the Julius Shulman Photography Archive with Wim de Wit, head, Special Collections and Visual Resources, and curator of architectural drawings, Getty Research Institute. Friday, October 14, 2005, 4:00-5:30pm Museum Lecture Hall LECTURES "Shooting Time: Julius Shulman and the Image of Contemporary Architecture" Sylvia Lavin, chair, Architecture and Urban Design, University of California, Los Angeles. Thursday, November 3, 2005, 4:00–6:00 p.m. Getty Research Institute Lecture Hall "A Continual Becoming: Rudolph Schindler's Discordant Modernism" Thomas S. Hines, professor, History and Architecture, University of California, Los Angeles. Thursday, December 1, 2005, 4:00–6:00 p.m. Getty Research Institute Lecture Hall FILM SCREENING AND DISCUSSION “Left Coast Modernism: Architecture and Urban Form in Los Angeles” Reyner Banham’s documentary Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles (1972, 52 min.) is the British architectural historian’s critical examination of Los Angeles as it was developing into a major metropolitan city at the end of the mid-century Modern movement, a period that photographer Julius Shulman documented so eloquently. Panelists include Amy Murphy, assistant professor, School of Architecture, University of Southern California, and Ed Dimendberg, associate professor, Film and Media Studies and Visual Studies, University of California, Irvine. Wednesday, December 7, 2005, 7:30 p.m. -

CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES the Gci Newsletter

CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES THE GCI NEWSLETTER SPRING 2020 CONSERVATION SCIENCE A Note from As this issue of Conservation Perspectives was being prepared, the world confronted the spread of coronavirus COVID-19, threatening the health and well-being of people across the globe. In mid-March, offices at the Getty the Director closed, as did businesses and institutions throughout California a few days later. Getty Conservation Institute staff began working from home, continuing—to the degree possible—to connect and engage with our conservation colleagues, without whose efforts we could not accomplish our own work. As we endeavor to carry on, all of us at the GCI hope that you, your family, and your friends, are healthy and well. What is abundantly clear as humanity navigates its way through this extraordinary and universal challenge is our critical reliance on science to guide us. Science seeks to provide the evidence upon which we can, collectively, make decisions on how best to protect ourselves. Science is essential. This, of course, is true in efforts to conserve and protect cultural heritage. For us at the GCI, the integration of art and science is embedded in our institutional DNA. From our earliest days, scientific research in the service of conservation has been a substantial component of our work, which has included improving under- standing of how heritage was created and how it has altered over time, as well as developing effective conservation strategies to preserve it for the future. For over three decades, GCI scientists have sought to harness advances in science and technology Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI Anna Flavin, Photo: to further our ability to preserve cultural heritage. -

Getty Research Institute | June 11 – October 13, 2019

Getty Research Institute | June 11 – October 13, 2019 OBJECT LIST Founding the Bauhaus Programm des Staatlichen Bauhauses in Weimar (Program of the State Bauhaus in Weimar) 1919 Walter Gropius (German, 1883–1969), author Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871–1956), illustrator Letterpress and woodcut on paper 850513 Idee und Aufbau des Staatlichen Bauhauses Weimar (Idea and structure of the State Bauhaus Weimar) Munich: Bauhausverlag, 1923 Walter Gropius (German, 1883–1969), author Letterpress on paper 850513 Bauhaus Seal 1919 Peter Röhl (German, 1890–1975) Relief print From Walter Gropius, Satzungen Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar (Weimar, January 1921) 850513 Bauhaus Seal Oskar Schlemmer (German, 1888–1943) Lithograph From Walter Gropius, Satzungen Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar (Weimar, July 1922) 850513 Diagram of the Bauhaus Curriculum Walter Gropius (German, 1883–1969) Lithograph From Walter Gropius, Satzungen Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar (Weimar, July 1922) 850513 1 The Getty Research Institute 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100, Los Angeles, CA 90049 www.getty.edu German Expressionism and the Bauhaus Brochure for Arbeitsrat für Kunst Berlin (Workers’ Council for Art Berlin) 1919 Max Pechstein (German, 1881–1955) Woodcut 840131 Sketch of Majolica Cathedral 1920 Hans Poelzig (German, 1869–1936) Colored pencil and crayon on tracing paper 870640 Frühlicht Fall 1921 Bruno Taut (German, 1880–1938), editor Letterpress 84-S222.no1 Hochhaus (Skyscraper) Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (German, 1886–1969) Offset lithograph From Frühlicht, no. 4 (Summer 1922): pp. 122–23 84-S222.no4 Ausstellungsbau in Glas mit Tageslichtkino (Exhibition building in glass with daylight cinema) Bruno Taut (German, 1880–1938) Offset lithographs From Frühlicht, no. 4 (Summer 1922): pp. -

Research Institute Grants

Getty Research Institute Grants Artistic Practice 2011/2012 Theme Year aT The GeTTY research insTiTuTe Artists mobilize a variety of intellectual, organizational, technological, and physical resources to create their work. This scholar year will delve into the ways in which artists receive, work with, and transmit ideas and images in various cultural traditions. At the Getty Research Institute, scholars will pay particular attention to the material manifestations of memory and imagination in the form of sketchbooks, notebooks, pattern books, and model books. How do notes, remarks, written and drawn observations reveal the creative process? In times and places where such media were not in use, what practices were developed to give ideas material form? In the ancient world, artists left traces of their creative process in a variety of media, but many questions remain for scholars in residence at the Getty Villa: What was the role of prototypes such as casts and models; what was their relationship to finished works? How were artists trained and workshops structured? How did techniques and styles travel? An interdisciplinary investigation among art historians and other specialists in the humanities will lead to a richer understanding of artistic practice. HoW To Apply Detailed instructions, application forms, complete theme statement and additional information are available online at www.getty.edu/foundation/apply Address inquiries to: Attn: (Type of Grant) The Getty Foundation 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 800 DeaDline los Angeles, CA 90049-1685 USA phone: 310 440.7374 nov 1 2010 E-mail: [email protected] Academy of fine arts, 1578. Research Library, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, California. -

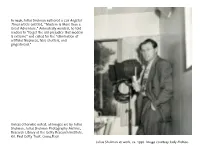

Julius Shulman

In 1946, Julius Shulman authored a Los Angeles Times article entitled, "Modern is More than a Great Adventure.” Animatedly worded, he told readers to "forget the old prejudice that modern is extreme" and called for the "elimination of artificial fireplaces, false shutters, and gingerbread." Unless otherwise noted, all images are by Julius Shulman. Julius Shulman Photography Archive, Research Library at the Getty Research Institute. ©J. Paul Getty Trust. (2004.R.10) Julius Shulman at work, ca. 1950. Image courtesy Judy McKee. As we reflect on his adventure promoting architecture and design, we realize there are even more stories to be told through his extensive archive. Julius Shulman photographing Case Study House #22, Pierre Koenig, photographed in 1960. Now housed at the Getty Research Institute, we find iconic images of modern living . Case Study House #22, Pierre Koenig, photographed in 1960. as well as some images of . gingerbread. Outtake of a Christmas cookie assignment for Sunset magazine, 1948. More than a great adventure, the Julius Shulman Photography Archive illustrates the lifelong career of Julius Shulman . Julius Shulman on assignment in Israel, 1959. in California . Downtown Los Angeles at night showing Union Bank Plaza, photographed in 1968. across the United States . Marina City, Bertrand Goldberg, Chicago, Illinois, photographed in 1963. and abroad. View of Ministry of Justice and Government Building from Senate Building, Oscar Niemeyer, Brasìlia, Brazil, photographed in 1977. Interspersed throughout the archive are handwritten thoughts . essays . occasional celebrity sightings . Actress Jayne Mansfield demonstrates an in-counter blender for NuTone Inc., 1959. and photographic evidence of his spirited sense of humor! The last shot of 153 images taken at Bullock’s Pasadena, Wurdeman and Becket, 1947. -

Visitor Info

VISITOR INFO Location 17985 Pacific Coast Highway, one mile north of Sunset Boulevard, overlooking the Pacific Ocean. The 64-acre site is approximately 25 miles west of downtown Los Angeles, and about 13 miles from the Getty Center. Admission Admission is always FREE. An advance, timed ticket is required and can be obtained online at www.getty.edu, or by phone at 310-440-7300. Each Villa ticket allows you to bring up to three children ages 15 and under in one car. Groups of nine or more must make reservations by phone. No walk-ins are permitted except for those arriving by public transportation. Passengers must have their Villa admission ticket hole-punched by the driver before exiting the bus in order to enter the Villa. Hours Wednesday–Monday, 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Closed Tuesday and on major holidays (January 1, July 4, Thanksgiving, and December 25) Parking $15 per car. Directions From Los Angeles, take the I-10 (Santa Monica Freeway) west until it turns into Route 1 (Pacific Coast Highway) going north along the Pacific Ocean. Continue on Route 1 for about five miles to the Getty Villa. Visitors must approach the Getty Villa from the south. Access to the Getty Villa is from the northbound right-hand lane of Pacific Coast Highway (PCH). -more- -more- Page 2 Public Transportation Metro Bus 434 stops near the Getty Villa entrance on Pacific Coast Highway. Call the MTA at (800) 266-6883 or TTY (800) 252- 9040 for more information. Visitors who take public transportation must have their Villa tickets hole-punched by the driver before exiting the bus. -

News from the Getty

The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 403 Tel 310 440 7360 Communications Department Los Angeles, California 90049-1681 Fax 310 440 7722 www.getty.edu [email protected] NEWS FROM THE GETTY DATE: December 15, 2011 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE GETTY RESEARCH INSTITUTE ACQUIRES MAN RAY ARCHIVES Personal datebooks, correspondence, photographs and ephemera enhance the Getty’s unparalleled collections on Man Ray Man Ray agendas and related materials, 1923-39. Man Ray (American, 1890-1976). Research Library, Getty Research Institute LOS ANGELES—The Getty Research Institute (GRI) announced today two complementary acquisitions concerning the artist and photographer Man Ray (b. Emmanuel Radnitzky, American, 1890-1976). “These archival materials, photographs, and published works are important additions to the collections at the Getty Research Institute,” said Thomas Gaehtgens, director of the Getty Research Institute. “Taken together with the substantial holdings of the artist’s work in the Getty Museum’s Department of Photographs, they make the Getty the premier North American repository for collections on Man Ray.” -more- Page 2 Adding to the GRI’s already significant Man Ray holdings, these two acquisitions, from different private sources, unearth unique and rarely studied material on the artist. One comprises an archive of manuscripts, correspondence, publications, photographs, ephemera, and art works concerning the artist and his wife, Juliet Man Ray, which were assembled by their longtime friends Michael and Elsa Combe-Martin. The agendas from 27 years of the artist’s career, covering 1923-40, 1951-58, and 1971, are the highlight of this collection. The illustrated agendas or calendar books that were kept by the expatriate artist during the 1920s and 1930s in Paris, when he was associated with the Dada and Surrealist groups, document his near-daily encounters and appointments with friends and colleagues such as Ernest Hemingway, Pablo Picasso, André Breton, and Lee Miller. -

Executive Compensation Process

THE J. PAUL GETTY TRUST EMPLOYER IDENTIFICATION NO. 95-1790021 SENIOR MANAGEMENT COMPENSATION Updated March 3, 2015 The Role of the Board of Trustees in Overseeing Senior Management Compensation The full Board of Trustees establishes the terms of the President’s employment and compensation. The Compensation Committee, a standing committee composed of independent members of the Board of Trustees, approves the compensation of the President’s direct reports. Trustees of the J. Paul Getty Trust receive no compensation for their service but are reimbursed for travel expenses incurred in fulfilling their duties as members of the Board. In addition, Trustees are eligible to participate in a matching gift program providing matching gift funds to eligible qualified public charities on a four-to-one basis up to an annual maximum matching amount of $60,000. The J. Paul Getty Trust Senior Management Compensation Policy The goal of the Getty’s compensation process is to pay salaries that are competitive for comparable positions at organizations similar in activities and scope. The performance and compensation of the President and Chief Executive Officer is reviewed and set by the Board of Trustees in executive sessions in the absence of the President and CEO. Compensation decisions regarding direct reports to the President are recommended by the President and CEO to the Compensation Committee for approval. Program Directors and Vice Presidents are eligible to participate in a matching gifts program providing matching gift funds to eligible qualified public charities on a four-to-one basis up to an annual maximum matching amount of $32,000. The Compensation Committee reviews and compares compensation levels for the President and his direct reports with those reported for analogous positions at comparable organizations. -

Press Release

NEWS FROM THE GETTY news.getty.edu | [email protected] DATE: March 20, 2019 MEDIA CONTACT: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Amy Hood Getty Communications (310) 440-6427 [email protected] GETTY RESEARCH INSTITUTE PRESENTS BAUHAUS BEGINNINGS Marking the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Bauhaus school, the exhibition explores the art, architecture, design, and philosophy of the school’s early years. Accompanied by the online exhibition Bauhaus: Building the New Artist At the Getty Research Institute, Getty Center Los Angeles June 11 – October 13, 2019 Los Angeles – The Bauhaus is widely regarded as the most influential school of art and design of the 20th century. Marking the 100th anniversary of the school’s opening, Bauhaus Beginnings on view at the Getty Research Institute from June 11 through October 13, 2019 examines the founding principles of the landmark institution. “For a century the Bauhaus has widely inspired modern design, architecture and art as well as the ways these disciplines are taught,” said Mary Miller, director of the Getty Research Institute. “However, the Joost Schmidt (German, 1893–1948), Form and Color Study, ca. 1929–1930, watercolor over graphite story of Bauhaus is not just the story of its on paper. Los Angeles, Getty Research Institute, 860972 teachers or most famous students. At the Getty Research Institute our archives are rich in rare prints, drawings, photographs, and other materials from some of the most famous artists to work at Bauhaus as well as students whose work, while lesser known, is extremely compelling and sometimes astonishing. Because of the breadth of our special collections we are able to offer a never-before-seen side of the Bauhaus along with more familiar images.” The J.