The United Nations Fraternity: Tau Delta Phi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines for Scholarships Theta Pi Chapter of Sigma Theta Tau Illinois

Guidelines for Scholarships Theta Pi Chapter of Sigma Theta Tau Illinois Wesleyan University Research/Awards Subcommittee The Research/Awards Subcommittee of the Leadership Succession Committee consists of three appointed chapter members and others as appointed who have experience in nursing education and/or research. The Research/Awards Subcommittee reviews applications, recommends individuals for scholarships, and monitors fund usage by recipients. A five-year record is kept of all recipients of scholarships, including recipients’ names and addresses, amounts of awards, and criteria used for selection of recipients. The Board of Directors approves the recommendations of the Research/Awards Subcommittee based upon availability of funds for scholarships. The treasurer distributes scholarship money to the recipients. Purpose of the Scholarship The purpose of the scholarship is to support outstanding nursing students who have the potential to advance nursing knowledge in the area of nursing science and practice. The fund provides money for one or more scholarships. Eligibility 1. Applicant is enrolled in a baccalaureate program in nursing, a higher degree program in nursing, or a doctoral program. 2. Preference will be given to applicants who are members of Theta Pi Chapter of STTI. Criteria for Selection 1. Quality of written goals 2. Contribution or potential contribution to nursing and public benefit 3. Availability of funds in the scholarship fund budget and number of applications received 4. Grade point average Amount of Award The amount of the award may vary from year to year, depending upon the funds requested, the number of requests, and the money available in the chapter scholarship fund. The scholarship may be used for any legitimate expense associated with academic study specified under eligibility. -

The Selnolig Package: Selective Suppression of Typographic Ligatures*

The selnolig package: Selective suppression of typographic ligatures* Mico Loretan† 2015/10/26 Abstract The selnolig package suppresses typographic ligatures selectively, i.e., based on predefined search patterns. The search patterns focus on ligatures deemed inappropriate because they span morpheme boundaries. For example, the word shelfful, which is mentioned in the TEXbook as a word for which the ff ligature might be inappropriate, is automatically typeset as shelfful rather than as shelfful. For English and German language documents, the selnolig package provides extensive rules for the selective suppression of so-called “common” ligatures. These comprise the ff, fi, fl, ffi, and ffl ligatures as well as the ft and fft ligatures. Other f-ligatures, such as fb, fh, fj and fk, are suppressed globally, while making exceptions for names and words of non-English/German origin, such as Kafka and fjord. For English language documents, the package further provides ligature suppression rules for a number of so-called “discretionary” or “rare” ligatures, such as ct, st, and sp. The selnolig package requires use of the LuaLATEX format provided by a recent TEX distribution, e.g., TEXLive 2013 and MiKTEX 2.9. Contents 1 Introduction ........................................... 1 2 I’m in a hurry! How do I start using this package? . 3 2.1 How do I load the selnolig package? . 3 2.2 Any hints on how to get started with LuaLATEX?...................... 4 2.3 Anything else I need to do or know? . 5 3 The selnolig package’s approach to breaking up ligatures . 6 3.1 Free, derivational, and inflectional morphemes . -

UCS) - ISO/IEC 10646 Secretariat: ANSI

ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2 N____ ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N5122 2019-12-31 ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 Universal Coded Character Set (UCS) - ISO/IEC 10646 Secretariat: ANSI DOC TYPE: Meeting minutes TITLE: Unconfirmed minutes of WG 2 meeting 68 Microsoft Campus, Redmond, WA, USA; 2019-06-17/21 SOURCE: V.S. Umamaheswaran ([email protected]), Recording Secretary Michel Suignard ([email protected]), Convener PROJECT: JTC 1.02.18 - ISO/IEC 10646 STATUS: SC 2/WG 2 participants are requested to review the attached unconfirmed minutes, act on appropriate noted action items, and to send any comments or corrections to the convener as soon as possible but no later than the due date below. ACTION ID: ACT DUE DATE: 2020-05-01 DISTRIBUTION: SC 2/WG 2 members and Liaison organizations MEDIUM: Acrobat PDF file NO. OF PAGES: 51 (including cover sheet) 2019-12-31 Microsoft Campus, Redmond, WA, USA; 2019-06-17/21 Page 1 of 51 JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2/N5122 Unconfirmed minutes of meeting 68 ISO International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 Universal Coded Character Set (UCS) ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2 N____ ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N5122 2019-12-31 Title: Unconfirmed minutes of WG 2 meeting 68 Microsoft Campus, Redmond, WA, USA; 2019-06-17/21 Source: V.S. Umamaheswaran ([email protected]), Recording Secretary Michel Suignard ([email protected]), Convener Action: WG 2 members and Liaison organizations Distribution: ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 members and liaison organizations 1 Opening Input document: 5050 Agenda for the 68th Meeting of SC2/WG2, Redmond, WA, USA. -

Pledge Test Study Guide

Theta Tau STUDY GUIDE This study guide has been prepared to assist local and colony members prepare for their Pledge Test. A written test on this material must be passed by each candidate for student membership in Theta Tau and each of those to be initiated into each Theta Tau chapter/colony. 1. What is the purpose of Theta Tau? To develop and maintain a high standard of professional interest among its members and to unite them in a strong bond of fraternal fellowship. 2. List the Theta Tau Region in which your school is located, and name of its Regional Director(s): see national officer list Regions: Atlantic, Central, Great Lakes, Gulf, Mid-Atlantic, Northeast, Southeast, Southwest 3. Define Theta Tau. A professional engineering fraternity 4. List the original name; date of founding; and the names of the Founders of Theta Tau (given name, initial, and surname), and the school, city, and state where founded. Society of Hammer and Tongs October 15, 1904 Erich J. Schrader, Elwin L. Vinal, William M. Lewis, Isaac B. Hanks University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 5. Give the name of the national magazine of the Fraternity, name of its Editor-in-Chief, and the duration of the subscription included in the initiation fee. The Gear of Theta Tau lifetime subscription 6. On the following list, check those fraternities which are competitive with Theta Tau, i.e., dual membership is not permitted by Theta Tau: [XX] Alpha Rho Chi [ ] Eta Kappa Nu [XX] Sigma Phi Delta [XX] Alpha Omega Epsilon [XX] Kappa Eta Kappa [ ] Chi Epsilon [ ] Alpha Phi Omega [ ] Pi Tau Sigma [ ] Tau Beta Pi [ ] Delta Sigma Phi [XX] Sigma Beta Epsilon [XX] Triangle 7. -

Endowment Book of Life

,ntv harua “Plants bear witness to the reality of roots.” - Maimonides This Endowment Book of Life was created by the members of the Harry Greenstein Legacy Society, and we gratefully dedicate it to them — the visionary men and women who gave life to the ancient Jewish prayer: Help us remember the Jewish past we have inherited, and keep us ever mindful of the Jewish future which we must secure and enrich. Our community flourishes today and will grow in perpetuity because they planted the seeds of caring and nurtured its roots. In these pages, they share their hopes and ideals with future generations — the Jews of tomorrow who will be inspired to renew this precious legacy in years to come. 1 Lynn Abeshouse The Yom Kippur War was my very first memory as a little girl of both my parents calling upon our community to help our Jewish people in a time of great crisis. Through the years, my family’s involvement within the Jewish community, and at The Associated, consisted of various philanthropic leadership positions – my father, Dr. George Abeshouse, chaired the Doctors’ campaign division on many occasions, my mother, Sara Offit Abeshouse, chaired Top Gifts and other campaign leadership positions within the Women’s Division, and my uncle, Morris W. Offit, chaired numerous positions both nationally and internationally. These were just some of the examples that became an integral part of my life lessons. I learned that it is every Jewish person’s obligation to assist those less fortunate and to always try one’s best to prioritize this value in one’s life. -

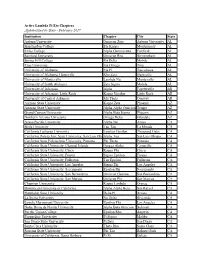

Active Lambda Pi Eta Chapters Alphabetized by State

Active Lambda Pi Eta Chapters Alphabetized by State - February 2017 Institution Chapter City State Auburn University Omicron Zeta Auburn University AL Huntingdon College Eta Kappa Montgomery AL Miles College Alpha Gamma Iota Fairfield AL Samford University Omicron Rho Birmingham AL Spring Hill College Psi Delta Mobile AL Troy University Eta Omega Troy AL University of Alabama Eta Pi Tuscaloosa AL University of Alabama, Huntsville Rho Zeta Huntsville AL University of Montevallo Lambda Nu Montevallo AL University of South Alabama Zeta Sigma Mobile AL University of Arkansas Alpha Fayetteville AR University of Arkansas, Little Rock Kappa Upsilon Little Rock AR University of Central Arkansas Mu Theta Conway AR Arizona State University Kappa Zeta Phoenix AZ Arizona State University Alpha Alpha Omicron Tempe AZ Grand Canyon University Alpha Beta Sigma Phoenix AZ Northern Arizona University Omega Delta Glendale AZ Azusa Pacific University Alpha Nu Azusa CA Biola University Tau Tau La Mirada CA California Lutheran University Upsilon Upsilon Thousand Oaks CA California Polytechnic State University, San Luis ObispoAlpha Tau San Luis Obispo CA California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Phi Theta Pomona CA California State University, Channel Islands Omega Alpha Camarillo CA California State University, Chico Kappa Phi Chico CA California State University, Fresno Sigma Epsilon Fresno CA California State University, Fullerton Tau Epsilon Fullerton CA California State University, Los Angeles Sigma Phi Los Angeles CA California State University, -

Fraternity and Sorority Conduct

Fraternity and Sorority Conduct Organization Incident Allegation Result Sanctions Date Alpha Phi Delta 12/14/18 Minor damage to hotel during formal Pending Pending () Kappa Alpha Psi 9/3/2018 Advertising open event with alcohol / Organization found responsible for Probation until January 1, 2019 () distribution of alcohol Fraternity and Sorority Social Event regulations 1,3,7 Kappa Sigma 7/24/2018 Hazing involving forced Organization found responsible for Probation until January 1, 2019, () memorization/yelling at new members health and safety violations following educational sanctions Delta Delta Delta 4/27/2018 Public consumption of alcohol on campus Organization found responsible for Probation until January 1, 2019 () health and safety violations Tau Delta Phi 9/22/2017 Reported sexual assault at fraternity event Organization found responsible for Withdrawal of University () by nonmember / Serving alcohol to minors health and safety violations/ Assault Recognition, eligible to reapply unfounded for recognition September 1, 2020 Alpha Chi Rho 9/14/2017 Noise violation from town Organization found responsible Social Probation until January 1, () 2018 Sigma Alpha Epsilon 9/4/2017 Residence Life reported intoxicated students Unfounded N/A () returned from SAE event Alpha Chi Rho 9/17/2016 Members smoking marijuana outside Organization found responsible for Chapter not allowed to host () organization’s social event health and safety violations events with alcohol until January 1, 2017 following educational sanctions Tau Delta Phi 10/12/2016 Serving alcohol to minors Organization found responsible for Social Probation until January 1, () health and safety violations 2017/ Educational sanctions Delta Phi Epsilon 10/6/2016 Serving alcohol to minors Organization found responsible for Social Probation until January 1, ( health and safety violations 2017 / Educational sanctions Alpha Phi Delta 9/17/2016 Noise complaint Organization found responsible Warning given () Sigma Beta Rho 9/9/2016 Noise violation from town Unfounded Warning given Fraternity, Inc. -

The Mathspec Package Font Selection for Mathematics with Xǝlatex Version 0.2B

The mathspec package Font selection for mathematics with XƎLaTEX version 0.2b Andrew Gilbert Moschou* [email protected] thursday, 22 december 2016 table of contents 1 preamble 1 4.5 Shorthands ......... 6 4.6 A further example ..... 7 2 introduction 2 5 greek symbols 7 3 implementation 2 6 glyph bounds 9 4 setting fonts 3 7 compatability 11 4.1 Letters and Digits ..... 3 4.2 Symbols ........... 4 8 the package 12 4.3 Examples .......... 4 4.4 Declaring alphabets .... 5 9 license 33 1 preamble This document describes the mathspec package, a package that provides an interface to select ordinary text fonts for typesetting mathematics with XƎLaTEX. It relies on fontspec to work and familiarity with fontspec is advised. I thank Will Robertson for his useful advice and suggestions! The package is developmental and later versions might to be incompatible with this version. This version is incompatible with earlier versions. The package requires at least version 0.9995 of XƎTEX. *v0.2b update by Will Robertson ([email protected]). 1 Should you be using this package? If you are using another LaTEX package for some mathematics font, then you should not (unless you know what you are doing). If you want to use Asana Math or Cambria Math (or the final release version of the stix fonts) then you should be using unicode-math. Some paragraphs in this document are marked advanced. Such paragraphs may be safely ignored by basic users. 2 introduction Since Jonathan Kew released XƎTEX, an extension to TEX that permits the inclusion of system wide Unicode fonts and modern font technologies in TEX documents, users have been able to easily typeset documents using readily available fonts such as Hoefler Text and Times New Roman (This document is typeset using Sabon lt Std). -

TCHS SCHOLARSHIP BULLETIN November 2020

TCHS SCHOLARSHIP BULLETIN November 2020 All scholarship applications are available on the school website and in Ms. Jones’s office. Feel free to email Ms. Jones at [email protected] for any additional questions. Prudential Spirit of Community Awards Deadline: November 10, 2020 Students in grades 5-12 who have volunteered in the past year - virtually or in person - can apply for local, state and national honors, including scholarships of up to $6,000. The Prudential Spirit of Community Awards, sponsored by Prudential Financial in partnership with the National Association of Secondary School Principals (NASSP), provides a wide range of opportunities to highlight the good works of both students and the schools that helped them along the path. Learn more about The Prudential Spirit of Community Awards, student eligibility and resources for schools at https://spirit.prudential.com PB&J Scholarship Deadline: December 31, 2020 This scholarship is trying to fill in the gap for high school seniors who don't have high GPAs and have experienced personal challenges that may not have allowed them to perform well academically, but who still have the drive to succeed. The scholarship awards range from $500 - $1,000 Students can apply through this link: https://scholarsapp.com/scholarship/pbj-scholarship Texas Student Housing Authority Scholarship Deadline: January 31, 2021 Texas Student Housing Authority scholarships are available to Texas High School graduating seniors, community college students, and university upper classmen who have previously graduated from a Texas High School. Applications are available in Ms. Jones’s office Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. Zeta Tau Lambda Chapter Scholarship Deadline: February 14, 2021 The Zeta Lamda Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. -

Jewish Fraternal Organizations of the Early 20Th Century Hal Bookbinder ([email protected])

Jewish Fraternal Organizations of the early 20th Century Hal Bookbinder ([email protected]) Our ancestors created a wide variety of organizations to provide mutual support, from religious to social, educational, insurance and burial services. “Landsmanshaften” brought together individuals who came from the same town in Europe. Sometimes established as lodges of a fraternal organization, like the Independent Order, Sons of Jacob. These organizations paralleled existing American ones incorporating the pomp and secrecy of Masonry, Pythians and Odd Fellows. These organizations provided a safety net through life and health insurance and offered social opportunities to lead and to be recognized. Hundreds of thousands of our immigrant ancestors participated during the heyday of these organizations in the first half of the 20th century. Most were male-focused. Women participated through auxiliaries and occasionally fully independent orders. Understanding these organizations provides important insights into the lives of our immigrant ancestors. Over a score of major Jewish Fraternal Organizations were formed between 1840 and 1920, including American Star Order Independent Order Western Star Improved Order of B’nai B’rith (now, B'nai Independent Order, B’nai B’rith B'rith International) Independent Workmen’s Circle of America Independent Order Ahavas Israel Jewish National Workers’ Alliance of America Independent Order B’rith Abraham Kesher Shel Barzel Independent Order B’rith Sholom Order of B’rith Abraham Independent Order Free Sons of Israel Order of the Sons of Zion (now, “B’nai Zion”) Independent Order of American Israelites Order of the United Hebrew Brothers Independent Order of Free Sons of Judah Progressive Order of the West Independent Order of Sons of Abraham United Order of the True Sisters, Inc. -

JCL to Honor Award Winners June 3 Closes Strong New Donors Show Support for Community Blanche B

May 24, 2013 14 SIVAN 5773 Community 1 Published by the Jewish Community of Louisville, Inc. www.jewishlouisville.org INSIDE Discover CATCH program to help chil- dren make healthy choices is coming to the JCC. PAGE 19 Communit■ ■ y FRIDAY VOL. 41, NO. 9 15 SIVAN 5773 MAY 24, 2013 Campaign JCL to honor award winners June 3 closes strong New donors show support for community Blanche B. Ottenheimer Lewis W. Josepth J. Kaplan Ron and Marie Award Cole Young Young Leadership Elsie P. Judah Award Abrams Volunteer by Stew Bromberg Madeline Leadership AwardAward Mag Davis andTeresa of the Year Vice President and Abramson Ben Vaughan Beth Salamon Barczy Keiley Caster Chief Development Officer Jewish Federation of Louisville he 2013 Annual Campaign for JCL TO HONOR the Jewish Federation of Louis- ville has officially closed. As of T today, we have received pledges AWARD WINNERS of $2,016,675. Thank you to all of you who support the Louisville Jewish com- munity. We know there are still pledges Arthur S. King JUNE 3 Ellen Faye that are in the works and these will be Award Garmon Award added to the campaign total so we might Lisa Moorman See story, page 5. Maggie Rosen have the greatest impact possible on our community, nationally and globally. I would like to share a few important facts about this year’s campaign. We have 199 new do- nors this year with combined contri- butions of $238,947, or an average gift Stuart Pressma of $1,200 each. We Student Leadership Stuart Pressma Stuart Pressma Stuart Pressma Stuart Pressma have ‘reclaimed’ 178 Stacey Marks Award and Joseph Student LeadershipStudent LeadershipStudent Leadership Student Leadership donors who have not Nisenbaum Award Flink Award Award Award Award Award donated to our com- Ben Koby Sophie Reskin Alanna Gilbert Jordyn Levine Jacob Spielberg Klaire Spielberg munity campaign over the past two years. -

Chapter Status Report

Chapter Status Report Chapter Effective Date Violations Sanctions Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority 9/1/16 Fell below the required standard of 5 members Probation: Viability Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity 9/1/16 Fell below the required standard of 5 members Probation: Viability Delta Sigma Theta Sorority 9/1/16 Fell below the required standard of 5 members Probation: Viability Iota Phi Theta Fraternity 9/1/16 Fell below the required standard of 5 members Probation: Viability Lambda Theta Alpha Sorority 9/1/16 Fell below the required standard of 5 members Probation: Viability Lambda Theta Phi Fraternity 9/1/16 Fell below the required standard of 5 members Probation: Viability Omega Psi Phi Fraternity 9/1/16 Fell below the required standard of 5 members Probation: Viability Zeta Phi Beta Sorority 9/1/16 Fell below the required standard of 5 members Probation: Viability Mu Sigma Upsilon Sorority 9/1/16 Fell below the required standard of 5 members Probation: Viability 1/15/17 Chapter GPA below required 2.8 Academic Status I Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity 9/1/16 Fell below the required standard of 5 members Probation: Viability 1/15/17 Chapter GPA below required 2.8 Academic Status I Tau Delta Phi Fraternity 10/1/16 Violations of Alcohol Policy Probation Lambda Tau Omega Sorority 1/15/17 Fell below the required standard of 5 members Probation: Viability Omega Psi Phi Fraternity 1/15/17 Chapter GPA below required 2.8 Academic Status I Alpha Chi Rho Fraternity 1/15/17 New Member Class GPA below required 2.8 Academic Status I Updated April 2017 Past Status