Poles' in Germany Engagement in Immigrant Organizations and Its Determinants Nowosielski, Michal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Henryk Chałupczak POLAND's STRATEGY to NEUTRALIZE THE

16 HENRYK CHAŁUPCZAK ESSAYS „Studies in Politics and Society” 9/2012 Henryk Chałupczak POLAND’S STRATEGY TO NEUTRALIZE THE GERMAN MINORITY’S PETITIONS AT THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS IN THE INTERWAR PERIOD 1. The Procedure The interwar system for protection of national minorities in Europe was based on commitments undertaken by several states that had fol- lowed from the so called small Treaty of Versailles, resolutions of the Council of the League of Nations that specified the conditions of its execution, and, as far as some states are concerned, conventions signed by those states. The principles to file petitions by the minorities in the states covered by the small Treaty of Versailles were laid down in the so called general procedure and an extraordinary procedure that – even though not included in the Treaty – followed from the Treaty’s inter- pretation. The first of those envisaged a few ways for the minorities to assert their rights, including putting in complaints – some types of the complaints required collaboration with a member of the League’s Council. Art. 12 of the Treaty was particularly important in this respect, according to which should a controversy arise over its interpretation, the controversial issue might be resolved by means of arbitrage (Kutrzeba 1925: 79–82). Regarding the extraordinary procedure, the resolution of the League’s Council of 22 October 1920 had been of fundamental im- portance, since it had granted actors who were not members of the Council – including the minorities – the right to inform the Council by means of petitions about infringements or threats to infringe upon the Treaty regulations. -

Chapter 1 of the Age of Migration

Copyrighted material_9780230355767. The Age of Migration Copyrighted material_9780230355767. Copyrighted material_9780230355767. The Age of Migration International Population Movements in the Modern World Fifth Edition Stephen Castles Hein de Haas and Mark J. Miller Copyrighted material_9780230355767. © Stephen Castles and Mark J. Miller 1993, 1998, 2003, 2009 © Stephen Castles, Hein de Haas and Mark J. Miller 2014 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First edition 1993 Second edition 1998 Third edition 2003 Fourth edition 2009 Fifth edition 2014 Published by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries ISBN 978–0–230–35576–7 hardback ISBN 978–0–230–35577–4 paperback This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

Protection of Minorities in Upper Silesia

[Distributed to the Council.] Official No. : C-422. I 932 - I- Geneva, May 30th, 1932. LEAGUE OF NATIONS PROTECTION OF MINORITIES IN UPPER SILESIA PETITION FROM THE “ASSOCIATION OF POLES IN GERMANY”, SECTION I, OF OPPELN, CONCERNING THE SITUATION OF THE POLISH MINORITY IN GERMAN UPPER SILESIA Note by the Secretary-General. In accordance with the procedure established for petitions addressed to the Council of the League of Nations under Article 147 of the Germano-Polish Convention of May 15th, 1922, concerning Upper Silesia, the Secretary-General forwarded this petition with twenty appendices, on December 21st, 1931, to the German Government for its observations. A fter having obtained from the Acting-President of the Council an extension of the time limit fixed for the presentation of its observations, the German Government forwarded them in a letter dated March 30th, 1932, accompanied by twenty-nine appendices. The Secretary-General has the honour to circulate, for the consideration of the Council, the petition and the observations of the German Government with their respective appendices. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page I Petition from the “Association of Poles in Germany”, Section I, of Oppeln, con cerning the Situation of the Polish Minority in German Upper Silesia . 5 A ppendices to th e P e t i t i o n ................................................................................................................... 20 II. O bservations of th e G erm an G o v e r n m e n t.................................................................................... 9^ A ppendices to th e O b s e r v a t i o n s ...............................................................................................................I03 S. A N. 400 (F.) 230 (A.) 5/32. -

Institute of National Remembrance

Institute of National Remembrance https://ipn.gov.pl/en/news/510,Celebration-of-66-Anniversary-of-the-Liberation-of-German-Concentrati on-Camp-KL-.html 2021-09-26, 10:30 02.05.2011 Celebration of 66 Anniversary of the Liberation of German Concentration Camp KL-Dachau - May 1, 2011 "Den Toten zur Ehre - Den Leben zur Mahnung" In Honor of the Dead - A Warning to the Living (Words carved on the monument at KL Dachau crematorium) On Sunday 1 May 2011 at the former Dachau concentration camp area the International Committee of Dachau (CID) and the Bavarian Memorials Foundation organized the ceremony of 66th anniversary of the camp liberation. KZ-Dachau, established on March 22, 1933, near the town of Dachau in Bavaria in the years 1939-1945 was the main center for extermination of hundreds of thousands of people from all over Europe. Most of the victims were Poles and Polish priests. Today the Dachau concentration camp is not only a place of remembrance and meditation on the fate of the victims, but also an important base of historical and ethical education. The task of this place is never to forget. William W. Quinn, U.S. Army Officer, wrote in his report to from the liberation of the camp: "Dachau 1933-1945 will always remain one of the most notorious symbols in the history of barbarism. Our troops there faced so terrible views as to be beyond belief, cruelties so enormous as to be incomprehensible for a normal mind. Dachau and death are synonymous. " Celebrations began in the Carmelite Convent Church of Holy Blood with ecumenical holy service celebrated by Catholic , Protestant and Orthodox Church priests. -

The Ethnic Composition of Schools and Students' Problem Behaviour in Four European Countries the Role of Friends Geven, S.; Kalmijn, M.; Van Tubergen, F

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The ethnic composition of schools and students' problem behaviour in four European countries The role of friends Geven, S.; Kalmijn, M.; van Tubergen, F. DOI 10.1080/1369183X.2015.1121806 Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Published in Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies License CC BY Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Geven, S., Kalmijn, M., & van Tubergen, F. (2016). The ethnic composition of schools and students' problem behaviour in four European countries: The role of friends. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42(9), 1473-1495. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1121806 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:24 Sep 2021 JOURNAL OF ETHNIC AND MIGRATION STUDIES, 2016 VOL. -

The Evolution and Sustainability of Seasonal Migration from Poland to Germany: from the Dusk of the 19Th Century to the Dawn of the 21St Century

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Kepinska, Ewa; Stark, Oded Working Paper The evolution and sustainability of seasonal migration from Poland to Germany: From the dusk of the 19th century to the dawn of the 21st century University of Tübingen Working Papers in Economics and Finance, No. 54 Provided in Cooperation with: University of Tuebingen, Faculty of Economics and Social Sciences, School of Business and Economics Suggested Citation: Kepinska, Ewa; Stark, Oded (2013) : The evolution and sustainability of seasonal migration from Poland to Germany: From the dusk of the 19th century to the dawn of the 21st century, University of Tübingen Working Papers in Economics and Finance, No. 54, University of Tübingen, Faculty of Economics and Social Sciences, Tübingen, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:21-opus-67906 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/73665 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Europe in Movement: Migration From/To Central and Eastern Europe

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Okólski, Marek Working Paper Europe in movement: Migration from/to Central and Eastern Europe CMR Working Papers, No. 22/80 Provided in Cooperation with: Centre of Migration Research (CMR), University of Warsaw Suggested Citation: Okólski, Marek (2007) : Europe in movement: Migration from/to Central and Eastern Europe, CMR Working Papers, No. 22/80, University of Warsaw, Centre of Migration Research (CMR), Warsaw This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/140806 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), -

Main Trends in International Migration

Part 1 MAIN TRENDS IN INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION The part concerning the main trends in interna- reversed in 1992-93, in part because of efforts by the tional migration is presented in four sections. The main receiving countries to tighten controls over first (I.A) looks at changes in migration movements migratory flows. From that time on, and until at and in the foreign population of the OECD member least 1997, entries of foreign nationals dropped countries. The second Section (I.B) focuses on the significantly despite the persistence of family migra- position of immigrants in the labour market. The tion and arrivals of asylum seekers, due in part to third (I.C) sheds particular light on two regions – the closing of other channels of immigration and a Asia and Central and Eastern Europe. This is new flare-up of regional conflicts. followed by an overview of migration policies (I.D), The resumption of immigration in the OECD which reviews policies to regulate and control flows, countries, which has been perceptible since the late along with the full range of measures to enhance the 1990s, was confirmed and tended to gather pace in integration of immigrants and developments in co- 2000 and 2001. It results primarily from greater operation at international level in the area of migra- migration by foreign workers, both temporary and tion. In addition, the issue of the integration of permanent. Conditions for recruiting skilled foreign immigrants into host-country societies is highlighted labour have been eased in most of the OECD in theme boxes to be found in Part I. -

My Spiritual Journey by Andrew Urbanowicz

My Spiritual Journey By Andrew Urbanowicz TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1 INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1 - My Early Childhood CHAPTER 2 - The Second World War CHAPTER 3 - Warsaw Uprising CHAPTER 4 - Prisoner of War Camps / End of the Second World War CHAPTER 5 - Switzerland / Escape to Italy / Joining Polish Armed Forces after the War in Italy / England Volume 2 CHAPTER 6 - My Civilian Life in England Before I Got Married CHAPTER 7 - My Married Life in England CHAPTER 8 - Coming to Canada Part 1 1957 – 1993 My Married Life in Canada Part 2 1993 – present My Life On My Own CHAPTER 9 - Reflections / Flashback Thoughts CHAPTER 10 - Visiting My Childhood Homeland Information tidbits Introduction All text in italics was imported from other sources All Bible quotations are from the New International Version (NIV) Only 12 copies of “My Spiritual Journey” Volume 1 were printed in 2015 INTRODUCTION “My Spiritual Journey” is a follow-up book to “God’s Leading in My Life,” which I published earlier. The two books need to be read side by side. My first book “God’s Leading in My Life” is an overview of my life, without too much detail or too many personal stories. It concentrated on high points only. The book’s purpose was to be my testimony as a witnessing tool to unbelievers, and an encouragement to believers. “My Spiritual Journey” is meant to fill those gaps, giving far more of my own personal reflections and details to the events that took place in my life. As such, I am going to follow similar chapters and high points in that story. -

Germans and Poles a Divided Past, a Common Future?

Germans and Poles A divided past, a common future? RESULTS OF THE POLISH-GERMAN BAROMETER 2018 A cooperation of: GERMANS AND POLES: A DIVIDED PAST, A COMMON FUTURE? 1 56% of the Poles and only 29% of the surveyed Germans like their neighbouring country. 73% of Poles identify with Europe very strongly or strongly. In Germany, 54% indicated such sentiments. 70% of Germans and 60% of Poles want the focus of both countries mutual relations to be on the present and the future and not on the past. 50% of Poles hold the view that the sacrifices that the Polish people have made throughout history have not been sufficiently recognised by the international public. 17% of Germans share this view. 64% of Poles describe Polish-German relations as good. Only 31% of Germans perceive them like that. 2 GERMANS AND POLES: A DIVIDED PAST, A COMMON FUTURE? Germans and Poles: a divided past, a common future? Results of the Polish-German Barometer 2018 The collapse of the Iron Curtain and the re- view is shared by half as many respondents. unification of Europe have brought Germany and The number of positive responses in Germany Poland closer together. In the face of the heavy has been falling significantly since Poland’s new burden of their shared past, what Germans and government came into power, whereas in Poland Poles have managed to achieve together in Eu- the percentage of positive re sponses has de- rope and for Europe is regarded as a success creased only slightly over the same period. story. Recently, controversy has arisen between the two neighbouring countries, especially with Poles identify with Europe more strongly regard to differing perceptions of the past. -

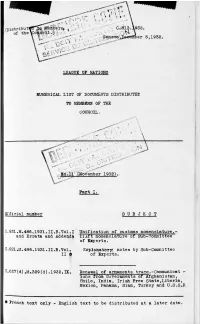

League of Nations Numerical List of Documents

LEAGUE OF NATIONS NUMERICAL LIST OF DOCUMENTS DISTRIBUTED TO MEMBERS OF THE COUNOIL. " • Q v o;. t - t .v* Wo.II’ (November 1932) Part I. Official number S U B J E C T 0,921,M.486.1931.II.B.Toi, I Unification of customs nomenclature,- and Errata and Addenda Diaf^ nomenclature of Sub-Oommittee of Experts. C.921 *M.486,1931. II.B.Vol, Explanatory?, notes by Sub-Commit tee II Û of Experts. C,627(d) ,M«.309(d) .1932.IX. Renewal of armaments truce.-Communicat - ions from Governments of Afghanistan, Chile, India, Irish Free State,Liberia, Mexico, Panama, Siam, Turkey and U.S.S.R 9 French text only - English text to be distributed at a later date. - 2 - Q, 663.M.320.1932.VII• Sino-Japanese dispute.- Addendum Addendun to the report of Committee of Enquiry. C,663,M .320.1932.VII. Supplementary documents to the report Annex of Commission of Enquiry. 0, 705(a).M.340(a),1932. Council, League (69th Session) Agenda for the November meeting. 0.705(b),M,340(b).1932. Supplementary list of items to Agenda of November meeting* 0.705(1).M.340(1).1932. Revised Agenda for November meeting. H.724.M.342.1632.VII. Commission of Enquiry for European Union (6th Session).- Minutes. .752.M.352.1932.1. Saar Basin.-Petition from the Association Oi of Pensioners of Altenwald and letter froc the Governing Commission. G ► 753,M.353.1932. Numerical list of documents distributed to Members of the League.-No,l0 (October 1932), C.754.M.354.1932.V Hungaro-Czechoslovak Mixed Arbitral and Annex <9 Tribunal.- Note by the Secretary-General and preliminary objection of the Hungarian Government to the judgments of Leeember 21,1931. -

Minority Rights Abuse in Communist Poland and Inherited Issues

Title Minority Rights Abuse in Communist Poland and Inherited Issues Author(s) Majewicz, Alfred F.; Wicherkiewicz, Tomasz Citation Acta Slavica Iaponica, 16, 54-73 Issue Date 1998 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/40153 Type bulletin (article) File Information 16_54-73.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP Mimorigy R ftghits Abwse im CogeeRffgm"nist Pekaredi apmdi llpmheffiged ffssaxes ARfred E Majewicz, 'Ibmasz Wicherkiewicz I. Throughout most of its independent existence Poland was a multiethnic country. In the interwar period 1918-1939 approximately one third ef its 36,OOO,OOO population consisted of non-Poles (mainly Ukrainians, Byelorussians, Lithuanians, Jews, Germans and Russians) who inhabited predominantly over half of its territory. The consequence of World War II was what was labeled as the reduction (or "return" ) ofPoiand to "its ethnic borders" forced by the allied powers. Poland was thus officially proclaimed a monoethnic state with no national minorities and this procla- mation was an essential and sensitive, though minor, part ofthe ideology imposed by the Communist ruiers .in spite of the fact that some twenty ethnic groups identified themselves as such and emphasized their (cultural, religious, linguistic, historical, etc.) separateness from others. "Ib secure firm control over these undesirable sentiments, after the post-Stalin Thaw the rulers created authoritatively certain institutional possi- bilitiesforsomecultivatingbysomeethnicgroupsofsomeaspectsoftheirethnicselfi identification. Nevertheless, the repertory of persecution and abuse of ethnic minority rights was quite impressive. It included: 1.1. Theso-called"verificationofautochthons"onterritoriesfbrmerlybe- longing to the German state (esp. Kashubian, Slovincian, the so-called Pomeranian, Mazurian population). l.2. Forceddeportations,displacements,resettlements,settlementsofnomadic groups, prohibition or administrative obstacles in granting rights to emigrate.