Annex I Introduction to Grove Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bus Services from Lewisham

River Thames to Broadwaters and Belmarsh Prison 380 Bus services from Lewisham Plumstead Bus Garage Woolwich for Woolwich Arsenal Station 180 122 to Abbey Wood, Thamesmead East 54 and Belvedere Moorgate 21 47 N 108 Finsbury Square Industrial Area Shoreditch Stratford Bus Station Charlton Anchor & Hope Lane Woolwich Bank W E Dockyard Bow Bromley High Street Liverpool Street 436 Paddington East Greenwich Poplar North Greenwich Vanbrugh Hill Blackwall Tunnel Woolwich S Bromley-by-Bow Station Eastcombe Charlton Common Monument Avenue Village Edgware Road Trafalgar Road Westcombe Park Sussex Gardens River Thames Maze Hill Blackheath London Bridge Rotherhithe Street Royal Standard Blackheath Shooters Hill Marble Arch Pepys Estate Sun-in-the-Sands Police Station for London Dungeon Holiday Inn Grove Street Creek Road Creek Road Rose Creekside Norman Road Rotherhithe Bruford Trafalgar Estate Hyde Park Corner Station Surrey College Bermondsey 199 Quays Evelyn Greenwich Queens House Station Street Greenwich Church Street for Maritime Museum Shooters Hill Road 185 Victoria for Cutty Sark and Greenwich Stratheden Road Maritime Museum Prince Charles Road Cutty Sark Maze Hill Tower 225 Rotherhithe Canada Deptford Shooters Hill Pimlico Jamaica Road Deptford Prince of Wales Road Station Bridge Road Water Sanford Street High Street Greenwich Post Office Prince Charles Road Bull Druid Street Church Street St. Germans Place Creek Road Creek Road The Clarendon Hotel Greenwich Welling Borough Station Pagnell Street Station Montpelier Row Fordham Park Vauxhall -

Neighbourhoods Linked to a Network of Green Spaces Neighbourhoods

LEWISHAM LOCAL PLAN EASTEASTEAST AREAAREAAREA NeighbourhoodsNeighbourhoods linkedlinked toto aa networknetwork ofof greengreen spacesspaces Lewisham’s East Area, with its continuous stretch of green spaces running from the riverside and Blackheath to Elmstead Wood in the south, has a suburban EASTEAST AREAAREA feel comprising a series of historic villages - Blackheath, Lee and Grove Park - Neighbourhoods linked to a originally built along the route to Greenwich. network of green spaces Following public consultation, we’ve focused on five areas across the borough. A local vision will help ensure that any development reflects the local character and is clear about what could happen on specific sites. The Local Plan sets a vision that by 2040, the Join an information session on Zoom abundant green space joined with the open Tuesday 16th March, 5.30pm -7pm expanses of Blackheath and its historic village will East Area (2nd session) be preserved and enhanced, strengthening this part More info and registration form here: of the borough as a visitor destination with broad https://lewishamlocalplan.commonplace.is/proposals/online-events appeal across Lewisham, London and the South East. Town and local centres will be strengthened with the redevelopment of Leegate Shopping Centre acting as a catalyst for the renewal of Lee Green. Burnt Ash, Staplehurst Road and Grove Park will continue to serve their neighbourhoods supported with public space improvements at station approaches. The ‘Railway Children’ urban park in Grove Park will herald better connections and further improvements to the linear network of green spaces which stretch throughout the area from the riverside and Blackheath in the north through to Chinbrook Meadows, through the Green Chain Walk and other walking and cycling routes. -

CHECK BEFORE YOU TRAVEL at Nationalrail.Co.Uk

Changes to train times Monday 7 to Sunday 13 October 2019 Planned engineering work and other timetable alterations King’s Lynn Watlington Downham Market Littleport 1 Ely Saturday 12 and Sunday 13 October Late night and early morning alterations 1 ! Waterbeach All day on Saturday and Sunday Late night and early morning services may also be altered for planned Peterborough Cambridge North Buses replace trains between Cambridge North and Downham Market. engineering work. Plan ahead at nationalrail.co.uk if you are planning to travel after 21:00 or Huntingdon Cambridge before 06:00 as train times may be revised and buses may replace trains. Sunday 13 October St. Neots Foxton Milton Keynes Bedford 2 Central Shepreth Until 08:30 on Sunday Sandy Trains from London will not stop at Harringay, Hornsey or Alexandra Palace. Meldreth Replacement buses will operate between Finsbury Park and New Barnet, but Flitwick Biggleswade Royston Bletchley will not call at Harringay or Hornsey. Please use London buses. Ashwell & Morden Harlington Arlesey Baldock Leighton Buzzard Leagrave Letchworth Garden City Sunday 13 October Hitchin Luton 3 Until 09:45 on Sunday Stevenage Tring Watton-at-Stone Key to colours Buses replace trains between Alexandra Palace and Stevenage via Luton Airport Parkway Luton Knebworth Hertford North. Airport Hertford North No trains for all or part of A reduced service will operate between Moorgate and Alexandra Palace. Welwyn North Berkhamsted Harpenden Bayford Welwyn Garden City the day. Replacement buses Cuffley 3 St. Albans City Hatfield Hemel Hempstead may operate. Journey times Sunday 13 October Kentish Town 4 Welham Green Crews Hill will be extended. -

Our Community, a Walk Through Bellingham, Downham and Whitefoot

OUR COMMUNITY A walk through Bellingham, Downham and Whitefoot Residents’ Annual Report 2013-14 3 WELCOME… OTHER LANDLORDS We’re pleased to introduce your Phoenix and hear what’s planned to improve Do make sure to visit our website residents’ annual report for 2013-14. Join us our community even more over the next www.phoenixch.org.uk to read the digital Throughout this report we compare our CONTENTS on a walk through our community. 12 months. version of this report, which includes lots of performance against other medium- additional information and videos. sized housing associations (5,000-10,000 OUR COMMUNITY GATEWAY Page 4 We’ve listened to your feedback from last It’s impossible to include EVERYTHING properties) in London and the south east OUR HOMES Page 8 year’s annual report and worked hard to that goes on within this report, so we’ve Finally, if you care about the future of our and nationally. This information comes make this year’s even better. highlighted the things that we feel are area and the community, we’d love to hear from Housemark, an organisation that OUR COMMUNITY Page 12 Phoenix is all of us. Our homes, our streets, the most important. We’ve examined our from you. Please join us as we work towards gathers performance information from OUR MONEY Page 16 our green spaces, tenants, leaseholders and performance against our agreed standards our vision of a better future for all. lots of other housing associations. OUR FUTURE Page 20 and we’re pleased to be able to say that we staff alike. -

Downham’S Attractions Demand Not to Be Left on the Margins

Creating opportunities for partiCipation and reCovery Cosmo Lewisham Community opportunities serviCe newsLetter issue 8 winter 2011 Right at the limits of Lewisham, Downham’s attractions demand not to be left on the margins. take d ownham – a diversion and discover the way to hidden treasures. Many of the roads are named from the legends of out and about king Arthur, so keep looking around for the holy grail. here it is no longer “the same old story” – there are lots of places to try out. Using the theme again of “five steps to wellbeing”, on page two we make many suggestions about places to visit in the new year and beyond. if anybody would like to recommend ideas to feature in the next newsletter, all submissions will be warmly welcomed. You can contact us at [email protected]. pause donna walker and for thought neil bellers winter is in Photograph: Grove my head, but Park station is southern eternaL spring Lewisham’s gateway to is in my heart. Downham and district. viCtor hugo (Jaiteg). in this issue stars shine hear us CeLebrating “today i bright roar hope feeL positive” sLam Community south east Lions worLd hearing pameLa’s team of 2010 football club voiCes Congress story page 3 pages 4&5 page 5 page 6 Cosmo No 8 Winter 2011 2 Cosmo five steps to wellbeing Co-editors Downham – out and about Frances Smyth Peter Robinson Connect Simply, connect with the people around you. 1With family, friends, colleagues and neighbours. At home, the newsletter team work, school or in your local community. -

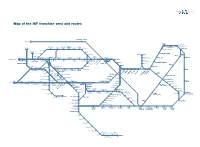

IKF ITT Maps A3 X6

51 Map of the IKF franchise area and routes Stratford International St Pancras Margate Dumpton Park (limited service) Westcombe Woolwich Woolwich Abbey Broadstairs Park Charlton Dockyard Arsenal Plumstead Wood Blackfriars Belvedere Ramsgate Westgate-on-Sea Maze Hill Cannon Street Erith Greenwich Birchington-on-Sea Slade Green Sheerness-on-Sea Minster Deptford Stone New Cross Lewisham Kidbrooke Falconwood Bexleyheath Crossing Northfleet Queenborough Herne Bay Sandwich Charing Cross Gravesend Waterloo East St Johns Blackheath Eltham Welling Barnehurst Dartford Swale London Bridge (to be closed) Higham Chestfield & Swalecliffe Elephant & Castle Kemsley Crayford Ebbsfleet Greenhithe Sturry Swanscombe Strood Denmark Bexley Whitstable Hill Nunhead Ladywell Hither Green Albany Park Deal Peckham Rye Crofton Catford Lee Mottingham New Eltham Sidcup Bridge am Park Grove Park ham n eynham Selling Catford Chath Rai ngbourneT Bellingham Sole Street Rochester Gillingham Newington Faversham Elmstead Woods Sitti Canterbury West Lower Sydenham Sundridge Meopham Park Chislehurst Cuxton New Beckenham Bromley North Longfield Canterbury East Beckenham Ravensbourne Brixton West Dulwich Penge East Hill St Mary Cray Farnigham Road Halling Bekesbourne Walmer Victoria Snodland Adisham Herne Hill Sydenham Hill Kent House Beckenham Petts Swanley Chartham Junction uth Eynsford Clock House Wood New Hythe (limited service) Aylesham rtlands Bickley Shoreham Sho Orpington Aylesford Otford Snowdown Bromley So Borough Chelsfield Green East Malling Elmers End Maidstone -

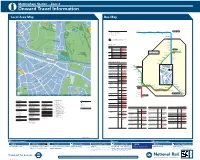

Local Area Map Bus Map

Mottingham Station – Zone 4 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 58 23 T 44 N E Eltham 28 C S E R 1 C Royalaal BlackheathBl F F U C 45 E D 32 N O A GolfG Course R S O K R O L S B I G L A 51 N 176 R O D A T D D H O A Elthamam 14 28 R E O N S V A L I H S T PalacPPalaceaala 38 A ROA 96 126 226 Eltham Palace Gardens OURT C M B&Q 189 I KINGSGROUND D Royal Blackheath D Golf Club Key North Greenwich SainsburyÕs at Woolwich Woolwich Town Centre 281 L 97 WOOLWICH 2 for Woolwich Arsenal E Ø— Connections with London Underground for The O Greenwich Peninsula Church Street P 161 79 R Connections with National Rail 220 T Millennium Village Charlton Woolwich A T H E V I S TA H E R V Î Connections with Docklands Light Railway Oval Square Ferry I K S T Royaloya Blackheathack MMiddle A Â Connections with river boats A Parkk V Goolf CourseCo Connections with Emirates Air Line 1 E 174 N U C Woolwich Common Middle Park E O Queen Elizabeth Hospital U Primary School 90 ST. KEVERNEROAD R T 123 A R Red discs show the bus stop you need for your chosen bus 172 O Well Hall Road T service. The disc !A appears on the top of the bus stop in the E N C A Arbroath Road E S King John 1 2 3 C R street (see map of town centre in centre of diagram). -

Characterisation Study Chapters 3-4.Pdf

3. BOROUGH WIDE ANALYSIS 3 BOROUGH WIDE ANALYSIS 3.1 TOPOGRAPHY 3.1.1 The topography of Lewisham has played a vital role in influencing the way in which the borough has developed. 3.1.2 The natural topography is principally defined by the valley of the Ravensbourne and Quaggy rivers which run north to south through the centre and join at Lewisham before flowing northwards to meet the Thames at Deptford. The north is characterised by the flat floodplain of the River Thames. 3.1.3 The topography rises on the eastern and western sides, the higher ground forming an essential Gently rising topography part of the borough's character. The highest point to the southwest of the borough is at Forest Hill (105m). The highest point to the southeast is Grove Park Cemetery (55m). Blackheath (45m) and Telegraph Hill (45m) are the highest points to the north. 3.1.4 The dramatic topography allows for elevated views from within the borough to both the city centre and its more rural hinterland. High points offer panoramas towards the city 42 Fig 18 Topography 2m 85m LEWISHAM CHARACTERISATION STUDY December 2018 43 3.2 GEOLOGY 3.2.1 The majority of the borough is underlain by the Thames Group rock type which consists mostly of the London Clay Formation. 3.2.2 To the north, the solid geology is Upper Chalk overlain by Thanet Sand. The overlying drift geology is gravel and alluvium. The alluvium has been deposited by the tidal flooding of the Thames and the River Ravensbourne. River deposits are also characteristic along the Ravensbourne. -

South East London Green Chain Plus Area Framework in 2007, Substantial Progress Has Been Made in the Development of the Open Space Network in the Area

All South East London Green London Chain Plus Green Area Framework Grid 6 Contents 1 Foreword and Introduction 2 All London Green Grid Vision and Methodology 3 ALGG Framework Plan 4 ALGG Area Frameworks 5 ALGG Governance 6 Area Strategy 8 Area Description 9 Strategic Context 10 Vision 12 Objectives 14 Opportunities 16 Project Identification 18 Project Update 20 Clusters 22 Projects Map 24 Rolling Projects List 28 Phase Two Early Delivery 30 Project Details 50 Forward Strategy 52 Gap Analysis 53 Recommendations 56 Appendices 56 Baseline Description 58 ALGG SPG Chapter 5 GGA06 Links 60 Group Membership Note: This area framework should be read in tandem with All London Green Grid SPG Chapter 5 for GGA06 which contains statements in respect of Area Description, Strategic Corridors, Links and Opportunities. The ALGG SPG document is guidance that is supplementary to London Plan policies. While it does not have the same formal development plan status as these policies, it has been formally adopted by the Mayor as supplementary guidance under his powers under the Greater London Authority Act 1999 (as amended). Adoption followed a period of public consultation, and a summary of the comments received and the responses of the Mayor to those comments is available on the Greater London Authority website. It will therefore be a material consideration in drawing up development plan documents and in taking planning decisions. The All London Green Grid SPG was developed in parallel with the area frameworks it can be found at the following link: http://www. london.gov.uk/publication/all-london-green-grid-spg . -

The London Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment 2017

The London Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment 2017 Part of the London Plan evidence base COPYRIGHT Greater London Authority November 2017 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk More London London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 Copies of this report are available from www.london.gov.uk 2017 LONDON STRATEGIC HOUSING LAND AVAILABILITY ASSESSMENT Contents Chapter Page 0 Executive summary 1 to 7 1 Introduction 8 to 11 2 Large site assessment – methodology 12 to 52 3 Identifying large sites & the site assessment process 53 to 58 4 Results: large sites – phases one to five, 2017 to 2041 59 to 82 5 Results: large sites – phases two and three, 2019 to 2028 83 to 115 6 Small sites 116 to 145 7 Non self-contained accommodation 146 to 158 8 Crossrail 2 growth scenario 159 to 165 9 Conclusion 166 to 186 10 Appendix A – additional large site capacity information 187 to 197 11 Appendix B – additional housing stock and small sites 198 to 202 information 12 Appendix C - Mayoral development corporation capacity 203 to 205 assigned to boroughs 13 Planning approvals sites 206 to 231 14 Allocations sites 232 to 253 Executive summary 2017 LONDON STRATEGIC HOUSING LAND AVAILABILITY ASSESSMENT Executive summary 0.1 The SHLAA shows that London has capacity for 649,350 homes during the 10 year period covered by the London Plan housing targets (from 2019/20 to 2028/29). This equates to an average annualised capacity of 64,935 homes a year. -

Re- Survey of S INC S / Report for Lewisham Planning Se Rvice

Re - survey of survey SINC s / Report for Report Lewisham PlanningLewisham Service Appendix 4: updated and new citations The Ecology Consultancy Re-survey of SINCs / Report for London Borough Lewisham Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation in Lewisham (BC) – Boundary change (U): SINC upgraded to Site of Borough Importance Name in blue: Proposed Site of Local Importance Name in red: Name change LeB01 – Grade II and Grade I merged into a single Borough designation LeB01 – Amended SINC number as a result of the above change or new site List of Sites of Metropolitan Importance M031 The River Thames and tidal tributaries (citation not amended) M069 Blackheath and Greenwich Park (Lewisham part updated only) M122 Forest Hill to New Cross Gate Railway Cutting M135 Beckenham Place Park (LNR) (BC) List of Sites of Borough Importance: LeB01 Brockley and Ladywell Cemeteries LeB02 Hither Green Cemetery, Lewisham Crematorium and Reigate Road Open Space (BC) LeB03 Downham Woodland Walk (LNR) (BC) LeB04 Pool River Linear Park (BC) LeB05 Hillcrest Estate Woodland LeB06 Grove Park Nature Reserve LeB07 Forster Memorial Park (BC) LeB08 Burnt Ash Pond Nature Reserve (LNR) LeB09 Horniman Gardens, Horniman Railway Trail and Horniman Triangle LeB10 Durham Hill (BC) LeB11 Dacres Wood Nature Reserve and Sydenham Park Railway Cutting (LNR) LeB12 Loats Pit LeB13 Grove Park Cemetery LeB14 Sue Godfrey Nature Park (LNR) LeB15 Honor Oak Road Covered Reservoir LeB16 St Mary's Churchyard, Lewisham LeB17 River Quaggy at Manor House Gardens LeB18 Mayow Park LeB19 Spring -

CHINBROOK ACTION RESIDENTS TEAM Big Local Plan September 2017 2017-2019 (Plan Years 2 and 3)

CHINBROOK ACTION RESIDENTS TEAM Big Local Plan September 2017 2017-2019 (Plan Years 2 and 3) 1 | P a g e CHINBROOK ACTION RESIDENTS TEAM BIG LOCAL PLAN 1. Introduction 2. Chinbrook Context 3. Partnership 4. Vision and Priority Areas o Priority 1 : Health & Well-being o Priority 2 : Parks & Green Spaces o Priority 3 : Education, Training & Employment o Priority 4 : Community & Belonging o Priority 5 : Routes out of Poverty o Priority 6 : Community Investment 5. Consulting the Community 6. Plan for Years 2 & 3 7. Appendices 2 | P a g e Introduction from our Vice Chairs “Welcome to Chinbrook Big Local, we call ourselves Chinbrook Action Residents Team, or ChART for short. Together we are working to make Chinbrook an even better place for people to live, work and play. We are pleased to introduce our second plan. We worked hard as a steering group to take on board the comments and view of local residents to forge our next set of priorities. There was a strong sense of the need for everybody to work together to tackle the harsh economic climate that is facing many people up and down the country which is why we have added a new priority, Routes out of Poverty. Over the last year I feel ChART has really started to make an impact in the area, doing what we intended which is galvanising local community solidarity based on what local people say they need, helping them to come together to do so. We have moved from people saying “ChART? What’s that” to “ChART, What are you up to?” and it was great to get so much positive feedback about our projects from the consultation exercise we undertook during the summer.