Africa Digest Vol. 2020-14

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

It Runs in the Family

TRENDS INTEL INDUSTRY REGION PURSUITS SUSTAINABLE BANKING STAWI PENSION EAST AFRICA TRAVEL GEMS NOT FOR SALE NOT Corporate Magazine | October2020 - January, 2021 A society in business It runs in Making Mulleys the Family Things cannot Secrets of building a great just fall family business into place Also in this issue, updates on the COVID 19 vaccine and how Biden will approach Africa The Ultimate Trade Finance Solutions 18 How Biden will approach Africa Biden has promised to “bring Our services include: to the presidency decades of • Pre-Shipment Finance/Pre-Export Finance foreign policy experience and a • LPO Financing/Supply Chain Financing demonstarted committment to Africa.” • Bills/Invoice Discounting Facilities • Stock Financing Facilities • Documentary Collections • Bank Guarantees/Bonds • Post-Import Finance 6 • Letters of Credit KCB bags major green finance deal CONTACT US TODAY: The bank is the first lender in Kenya and private sector entity Call: 0711 087 000 or 0732 187 000 to receive this accreditation Email: [email protected] cementing the sustainability Web: www.kcbgroup.com thought leadership efforts within the Group 44 Side-stepping the common pitfalls of family businesses The challenges of family businesses can be summed up to governance and succession 10 First annuity road paves way for more The road construction contract 12 was awarded to Intex Raf Construction Company at a cost Will Africa get the short end of the vaccine stick again? of KShs8 billion and financed by Kenya among countries in which trials -

Hy 2020 Results

HY 2020 RESULTS 1 CUSTOMERS 24.6 MILLION OUR REGIONAL PRESENCE 359 BRANCHES 1,082 ATMS, Banking Businesses: 23,192 AGENTS & MERCHANTS •KCB Bank Kenya •KCB Bank Tanzania STAFF •KCB Bank South Sudan 7,814 •KCB Bank Rwanda •KCB Bank Uganda •KCB Bank Burundi KCB BANK KENYA (ETHIOPIA •National Bank of Kenya KCB BANK REPRESENTATIVE •Ethiopia Rep. Office SOUTH SUDAN OFFICE ) KCB BANK KENYA Other Investments: KCB BANK NATIONAL BANK OF KENYA UGANDA • KCB Capital Limited KCB INSURANCE AGENCY KCB FOUNDATION • KCB Insurance Agency KCB CAPITAL KCB BANK • KCB Foundation RWANDA • Kencom House Limited KCB BANK KCB BANK BURUNDI TANZANIA 2 OUR FOOTPRINT Branches 12 Ethiopia South ATMs 3 Sudan Agents 42 (Representative Office Staff 118 with 1 staff) Touch Points: Branches 15 Uganda ATMs 18 Agents 530 Branches 300 Staff 271 ATMs 357 Kenya Agents 13,412 Branches 12 Staff 6,774 ATMs 25 Rwanda Agents 415 Staff 249 Branches 14 ATMs 15 Branches 6 Tanzania Agents 172 ATMs 7 Staff 274 Burundi Agents 185 Staff 127 3 CREDIT RATINGS RATING AGENCY SOVEREIGN KCB BANK KENYA Credit Ratings at par with the Sovereign Rating B2 (Negative) B2 (Negative) B+/B B+/B (Negative) (Negative) 4 KCB 2JIAJIRI 2JIAJIRI BENEFICIARIES AGRIBUSINESS PROGRAMME 19,080 PER SECTOR BUILDING AND HIGHLIGHTS CONSTRUCTION BEAUTY AND 9,910 PERSONAL CARE AUTOMOTIVE 3,480 ENGINEERING 2,083 FUTURE OF 2JIAJIRI DOMESTIC Catalyze job and wealth SERVICES creation for at least 1,638 36,706 2,000,000 ICT youth engaged in the informal BENEFICIARIES TO 515 DATE sector within Eastern Africa 5-year investment of over KShs 50 billion Male : Female Ratio to nurture and grow youthful and Kenya 35,949 SME entrepreneurs Tanzania ‘Young Africa Works’ 54:46 357 Rwanda KShs 10 billion funding 300 from the MasterCard Foundation Uganda to scale up the Bank’s 2jiajiri job 100 creation programme 5 KCB FOUNDATION Peter Kanyi, Owner, D-DEKX Autocare, Nairobi CASE STUDIES • Studied mechanical and electrical engineering at Eastlands College of Technology under 2jiajiri. -

Table of Contents

Weekly report - Week 35 Market Perfomance P revious T oday %Change Market Summary Shares traded 125,158,500 358,870,700 186.7% It was a mixed bag for the NSE Last week. After a very tumultuous week in the banking industry that Equity Turnover (KES) 2,670,283,939 6,726,668,014 151.9% saw banking stocks lose over 40bn on the market, Banks bounced back mainly due to investors who Market Cap (KES Bill) 1,944 1,931 -0.7% were keen to take advantage of the low entry levels for banks stocks. Most activity was seen on Market Cap (USD Mil) 19 19 -0.6% Safaricom where investors were rushing to lock in the ordinary and special dividend before book NSE-20 Share Index 3,217 3,188 -0.9% closure. Other counters that registered elevated activity were KCB Group, Equity bank and Co- NSE All Share Index 135 134 -0.7% 3,552 3,485 operative bank that witnessed activity mostly from investors that were taking advantage of the low NSE 25 Share Index -1.9% 91-day Treasury Bills 8.607 8.258 -4.1% banking valuations as well as investors fleeing to value. 182-day Treasury Bills 11.182 11.125 -0.5% All the main indices closed the week in the red.The Alsi, NSE 20 and NSE 25 shed 0.67%, 0.89% and 364-day Treasury Bills 11.982 11.502 -4.0% 1.87% respectively to close at 134.6, 3,187.87 and 3,485.42. Top Gainers & Losers Top gainers W eek Close w-o-w % Shares Traded Gainers Following news that Kuramo Capital had agreed to acquire about 25% percent of Transcentury’s Trans-Century Ltd 6.6 45.6% 52,500 Housing Finance Group Ltd 16.7 19.4% 312,300 shareholding in exchange for 2.0bn cash injection (a big premium on the price of Kes 4.50), NIC Bank Ltd 27.8 15.6% 486,900 Transcentury’s share prices soared 45.5% to close the week at Kes 6.60 from Kes 4.50 the previous Eveready East Africa Ltd 2.2 13.2% 14,200 Barclays Bank of Kenya Ltd 9.7 12.9% 5,925,700 Friday. -

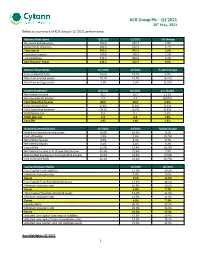

KCB Group Plc – Q1'2021

KCB Group Plc – Q1’2021 28th May, 2021 Below is a summary of KCB Group’s Q1’2021 performance: Balance Sheet Items Q1'2020 Q1'2021 y/y change Net Loans and Advances 553.9 597.1 7.8% Government Securities 202.6 212.1 4.7% Total Assets 947.1 977.5 3.2% Customer Deposits 740.4 749.4 1.2% Total Liabilities 811.5 830.0 2.3% Shareholders’ Funds 135.5 147.5 8.8% Balance Sheet Ratios Q1'2020 Q1'2021 % point change Loan to Deposit Ratio 74.8% 79.7% 4.9% Return on average equity 20.1% 13.9% (6.2%) Return on average assets 3.1% 2.0% (1.1%) Income Statement Q1'2020 Q1'2021 y/y change Net Interest Income 15.1 16.7 11.1% Net non-Interest Income 7.9 6.3 (20.0%) Total Operating income 23.0 23.0 0.4% Loan Loss provision (2.90) (2.86) (1.3%) Total Operating expenses (14.0) (13.9) (0.8%) Profit before tax 8.9 9.1 2.2% Profit after tax 6.3 6.4 1.8% Core EPS 1.95 1.98 1.8% Income Statement Ratios Q1'2020 Q1'2021 %point change Yield from interest-earning assets 10.8% 10.9% 0.1% Cost of funding 2.8% 2.6% (0.2%) Net Interest Spread 8.0% 8.3% 0.3% Net Interest Margin 8.1% 8.4% 0.3% Cost of Risk 12.6% 12.4% (0.2%) Net Interest Income as % of operating income 65.6% 72.6% 7.0% Non-Funded Income as a % of operating income 34.4% 27.4% (7.0%) Cost to Income Ratio 61.1% 60.4% (0.7%) Capital Adequacy Ratios Q1'2020 Q1'2021 Core Capital/Total Liabilities 17.1% 19.2% Minimum Statutory ratio 8.0% 8.0% Excess 9.1% 11.2% Core Capital/Total Risk Weighted Assets 17.1% 18.2% Minimum Statutory ratio 10.5% 10.5% Excess 6.6% 7.7% Total Capital/Total Risk Weighted Assets 19.0% 21.8% Minimum Statutory ratio 14.5% 14.5% Excess 4.5% 7.3% Liquidity Ratio 40.1% 37.3% Minimum Statutory ratio 20.0% 20.0% Excess 20.1% 17.3% Adjusted core capital/ total deposit liabilities 17.5% 19.4% Adjusted core capital/ total risk weighted assets 17.5% 18.3% Adjusted total capital/ total risk weighted assets 19.4% 21.9% Key Highlights Q1’2021 1 KCB Group Plc – Q1’2021 28th May, 2021 KCB Group’s restructured loan book stands at Kshs 102.5 bn, representing 18.8% of its loan book which stood at Kshs 597.1 bn as at Q1’2021. -

Integrated Report & Financial Statements

INTEGRATED REPORT & 2019 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Regulated by the Central Bank of Kenya 2 2019 Integrated Report & Financial Statements INTEGRATED REPORT & 2019 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS About this report he KCB Group Plc. Integrated Report and Financial Statement 2019 provides a balanced and Tcomprehensive view of the Group’s performance as part of our continuous efforts to enhance disclosure and keep our stakeholders well informed. The Report has been prepared for the period of January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2019 and covers the business activities of the KCB Group. Framework The report has been prepared in compliance with global best practice and prudent accounting frameworks for existing and prospective investors. It is aligned to the provisions of the Companies Act, 2015, Capital Markets Authority (CMA) guidelines, the Nairobi Securities Exchange (NSE) Listings Manual, and Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) Prudential Guidelines. This report is also in compliance with the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) Guidelines. The Group’s Annual Financial Statements were prepared in accordance with the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). The report is part of our commitment to be transparent and accountable to our stakeholders. Assurance The Annual Financial Statements for the Group, KCB Bank Kenya, KCB Bank South Sudan, KCB Bank Rwanda and KCB Bank Burundi were audited by KPMG. KCB Bank Tanzania was audited by PwC while KCB Bank Uganda was audited by EY. The Annual Financial Statements of National Bank of Kenya were audited -

Cytonn Report a Product of Cytonn Technologies

Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) in the Real Estate Industry in Kenya, & Cytonn Weekly #19/2021 Equities Markets Performance During the week, the equities market recorded mixed performance, with NSE 20 recording a marginal gain of 0.04% respectively, while NASI and NSE 25 declined by 3.1% and 3.7%. This week’s performance took their YTD performance to gains of 9.0% and 5.2%, for NASI and NSE 25, respectively, and a loss of 0.5% for NSE 20. The equities market performance was driven by gains recorded by stocks such as DTB-K and BAT which gained by 1.2% and 0.7%, respectively. The gains were however weighed down by losses recorded by stocks such as Safaricom and Co-operative Bank which declined by 3.4% and 1.2%, respectively. Equities turnover increased by 14.7% to USD 28.6 mn, from USD 24.9 mn recorded the previous week, taking the YTD turnover to USD 433.5 mn. Foreign investors turned net sellers during the week, with a net selling position of USD 5.4 mn, from a net buying position of USD 6.8 mn recorded the previous week, taking the YTD net selling position to USD 7.9 mn. The market is currently trading at a price to earnings ratio (P/E) of 12.7x, which is 1.5% below the historical average of 12.9x, and a dividend yield of 3.6%, 0.5% points below the historical average of 4.1%. Key to note, NASI’s PEG ratio currently stands at 1.4x, an indication that the market is trading at a premium to its future earnings growth. -

KCB Group Plc Q3 2020 Results

KCB Group Plc Q3 2020 Results Q3 2020 RESULTS Group Macro Economic Channel Financial Overview Highlights Performance Performance KCB Group Plc Q3 2020 Results 2020 Plc Q3 Group KCB Overview Group Group 2 3 KCB Group Plc Q3 2020 Results Our Regional Presence 22.9 MILLION KCB BANK KENYA (ETHIOPIA Banking Businesses: CUSTOMERS REPRESENTATIVE •KCB Bank Kenya OFFICE ) •KCB Bank Tanzania •KCB Bank South Sudan •KCB Bank Rwanda 360 BRANCHES KCB BANK •KCB Bank Uganda SOUTH SUDAN 1,090 ATMS •KCB Bank Burundi KCB BANK KENYA •National Bank of Kenya 23,230 AGENTS & NATIONAL BANK OF KENYA •Ethiopia Rep. Office KCB BANK UGANDA KCB INSURANCE AGENCY MERCHANTS KCB FOUNDATION KCB CAPITAL Other Investments: KENCOM HOUSE LIMITED • KCB Capital Limited KCB BANK RWANDA STAFF • KCB Insurance Agency KCB BANK BURUNDI • KCB Foundation 7,644 • Kencom House Limited KCB BANK TANZANIA 4 KCB Group Plc Q3 2020 Results Our Footprint Touch Points: Branches 12 Branches 15 ATMs 3 ATMs 18 Agents 45 Agents 465 Staff 115 Staff 254 Branches 13 Branches 6 ATMs 26 ATMs 7 Agents 431 Agents 98 Staff 247 Staff 125 Branches 300 Branches 14 ATMs 488 ATMs 15 Agents 14,195 Agents 200 Staff 6,616 Staff 276 1 Staff 5 KCB Group Plc Q3 2020 Results Operating Environment Highlights RESTRUCTURED LOANS Kenya Banking Sector Total restructured loans, 38% of the total banking KShs1.12T sector loan book. Kenya’s banking sector continues to remain stable and LIQUIDITY resilient in the face Liquidity availed by the lowering of CRR advanced of the pandemic with strong liquidity 92% to customers, KShs. -

H1 2021 Investor Presentation 19 August 2021 2

1 H1 2021 INVESTOR PRESENTATION 19 AUGUST 2021 2 Group Overview KCB’s Beyond Banking Strategy 3 Our Strategic Our 2023 Thrusts Aspirations CES Customer first, <15% Total assets with leading value Strategy Vision KES 1.5Tr NPS propositions 55+ Step change in CIR efficiency & productivity The very best 42% in customer experience, driving NFI Digital leader & digital a digital future 40% to the core PBT from subsidiaries 20% Scale to achieve regional relevance LARGEST FOOTPRINT IN THE REGION 4 26.8 M Customers 7,573 Staff 354 Branches 1,103 ATMs 26,394 Agents & POS / Merchants Kenya Bank National Bank of KCB Bank KCB Bank KCB Bank KCB Bank KCB Bank Ethiopia Rep Kenya Kenya Tanzania Burundi Rwanda Uganda South Sudan Office Branches 201 Branches and agencies 94 Branches 14 Branches 6 Branches 13 Branches 13 Branches 13 1 Staff ATMs 397 ATMs 105 ATMs 15 ATMs 8 ATMs 26 ATMs 15 ATMs 4 Agents 15,273 Agents 443 Agents 263 Agents 195 Agents 492 Agents 420 Agents 43 Staff 4,827 Staff 1,680 Staff 291 Staff 134 Staff 239 Staff 269 Staff 132 Other investments: KCB Insurance Agency, KCB Foundation, KCB Capital OUR ORGANISATION STRUCTURE 5 Board HR & AUDIT & RISK OVERSIGHT STRATEGY & IT NOMINATIONS GOVERNANCE Group CEO & MD Reporting to the Board & executing delegated powers Executive Committee General Management Assets & Liabilities Group Operational Risk & Management Credit Committee Management Committee Compliance Committee Risk Committee RATINGS 6 KCB BANK KENYA 2019 2020 2021 Credit ratings at par with the sovereign Rating B2 B2 B2 rating. Outlook Stable Negative Negative Credit rating affirmed KCB’s: • Solid profitability metrics • Stable deposit-based funding structure, and; • Strong capital buffers AWARDS 7 ❖ Best Bank in Kenya by: The Banker ❖ Global Finance World’s Best Bank Awards. -

2013 Sustainability Report

KCB Group Sustainability Report 1 Contents Introduction 2 Report Boundary 3 Chairman’s Report 4 CEO’s Statement 6 Key Highlights of our Performance 8 About KCB 10 Key Highlights from our Regional Operations 10 KCB Sustainability Vision 2013 12 Key Achievements in 2013: 12 Our 10 Point Action Plan 13 Our Customers 14 KCB Micro Banking for Innovative Minds 14 Customer Satisfaction 14 Aligning to the New Regulatory Environment 15 Financial Stability 16 Reducing Risk by Embracing Centralised System 16 Risk 17 KCB Revenues and Costs 18 Economic Sustainability KCB Foundation: Up-Skilling Small Business 19 Economic Sustainability 20 Increasing Access through Agency Banking 20 Contributions to Society 20 Staff Numbers 20 Staff Training 21 Staff Gender Balance 21 Staff Recruitment 22 Staff Separations 22 Banking the Unbanked 23 Social Sustainability 24 Reaching out to Rural Entrepreneurs 24 Procurement Policy 24 Making Secondary Education Affordable 25 Environmental Sustainability 26 Investing in the Sun 26 KCB’s Carbon Footprint 26 Helping Communities to Benefit from Re-afforestation 27 Our Progressive Performance 28 Financial 28 People and Values 28 Environment 30 Additional Notes/ Assumptions for Environmental Data 30 GRI Indicator Tabletor Table 31 2 Report Boundary since 2007 since 2006 Uganda South Sudan permanent permanent 336employees 408employees 16 ATMs 14 Branches 27ATMs 21Branches since 2008 since 1896 Rwanda Kenya permanent permanent 316employees 4011employees 19ATMs 11Branches 877ATMs 177Branches since 2012 since 1997 Burundi Tanzania permanent permanent 54 employees 250employees 2ATMs 1Branch 14ATMs 12Branches Figure 1: KCB Key Facts and Operating Regions The boundary of this report includes all KCB operations for the 2011, 2012 and 2013 years. -

Nimai Africa Financial Services Fund

NIMAI AFRICA FINANCIAL SERVICES FUND NEWSLETTER – MAY’20 KEY HIGHLIGHTS NIMAI NEWSLETTER COVID has emerged as one of the biggest Nimai Capital believes the short-term impact of challenges globally & investment manager COVID & downgrade of Kenya by Moody’s will be expects situation to stabilize & improve in severe on Financial Services Companies in East FYH20 Africa, higher NPLs & lower liquidity but higher demand for credit Nimai Africa Fund is progressing well with its Nimai Capital sees an opportunity to invest in Fund raise & has raised $25 Mn in hard & soft healthy Banks, NBFIs & Fintechs as they come out commitments from investors globally to raise capital to shore up their Balance Sheets & capture market vacated by weaker players Nimai Africa Fund is targeting First Close at Manish Parmar, Director Business Development, $35-40 Mn from Investors in Africa, Middle Victoria Commercial Bank & Sam Wanjohi, CEO & East & India between September – Founder, Popote Pay have also shared their views December’20 on the current situation of FS space in East Africa East Africa has been active from Fund raising for Nimai Capital sees faster adoption of digital Funds & New deal activities between Sept’19 & modes for Financial services globally & expects May’20. 5 Funds raised capital from international significant opportunities & demand for Fintech LPs & 9 Companies raised capital from several Companies local & global Funds. Fintechs raised $125 Mn across 6 deals Nimai’s Investment Team represented the Listed Kenyan Banks, Insurance & Financial Fund on speaking sessions held in Kenya, Saudi Services Companies performed better than global Arabia & Sri Lanka on Fund raising in times on peers, average 20% correction see in Banking Covid & Private Equity simplified stocks compared to 30-35% corrections across other emerging markets We are pleased to share with you that we have initiated a knowledge series where we will invite industry participants to share their views on various aspect of Private Equity & Venture Capital Industry. -

KCB Group Stock Rating Target Price Closing Price Buy KES62.8 KES37.6

27 November 2020 KCB Group Stock Rating Target Price Closing Price Buy KES62.8 KES37.6 Equity the beneficiary as KCB chases yet more What's Changed From To underproductive assets Company Update Banks. Kenya Rating: $RECO $ Target Price $ISO $$TP$ Potential acquisition of ABC Tanzania and BRP Rwanda KCB Group’s press release yesterday morning indicates that the bank is in discussions with the Atlas Mara Group to potentially acquire: i) a 62.06% stake in Banque Populaire Du Rwanda (BPR); and ii) a 96.6% stake in African Banking Corporation Tanzania Limited (ABCT). In addition, assuming that the BPR deal is successful, the bank intends to acquire the minority shareholders’ stake (37.94%) at the same acquisition multiple. Based on our calculations, we estimate the size of the transaction could be c.KES3.5bn-KES5.5bn (depending on whether the bank will be able to acquire BRP’s minority shareholders’ stake). We believe this will be another poor acquisition, if completed After sinking in KES6.2bn to acquire NBK (NPL ratio of +50%, CAR of 10.3%, and negligible ROE as of 9M20) less than twelve months ago, we think this could be yet another poor transaction by KCB, as: i) the inorganic growth as a result of the acquisition (+4.4% increase in loans and +6.7% increase in deposits) is not sufficient to offset the subsequent management distraction, especially as this growth could have been achieved organically (KCB Group’s 9M20 loans and deposits are up 7.9% and 12.5% YTD, respectively); ii) the underlying assets have low profitability, in both absolute -

ABIS 2019 Post Event Report

NAIROBI, KENYA | 19-20 FEBRUARY 2019 | WWW.AFRICABFSI.COM POST EVENT REPORT DIRECTOR’S NOTE Dear Participant, On behalf of Tradepass, I take immense pleasure in welcoming you to the inaugural edition of Africa BFSI Innovation Summit 2019. Being the inaugural edition, ABIS 2019 has attracted 350+ participants from the BFSI and technology industries, making it the largest Banking, Financial Services and Insurance summit in East Africa. The participation of leading local and international speakers representing some of the top banks, insurance and ȴQDQFLDOVHUYLFHFRPSDQLHVZLOOEULQJWRWKHIRUHQHZLQIRUPDWLRQDQGEXVLQHVVGHYHORSPHQWRSSRUWXQLWLHV 2YHUWKHFRXUVHRIWKHVHWZRGD\VWKHVXPPLWZLOOFRYHUFXWWLQJHGJHWRSLFVVXFKDV'LJLWDO%DQNLQJ&XVWRPHU([SHULHQFH0LFURȴQDQFH5LVNDQG &\EHUVHFXULW\'LJLWDO.<&&RUH%DQNLQJ3D\PHQWVDQG5HWDLO%DQNLQJDPRQJVWPDQ\RWKHUV$VSDUWRIWKHFXUUHQWHGLWLRQRIWKHFRQIHUHQFHDJHQGDD VHOHFWLRQRIRYHUSUHVHQWDWLRQVZLOOEHIHDWXUHGDORQJZLWKSDQHOGLVFXVVLRQVDQGȴUHVLGHFKDWVWKDWZLOOWKURZOLJKWRQVRPHRIWKHODWHVW technologies and innovations which play a key role in the evolving BFSI landscape.A series of interactive panel discussions and an array of networking sessions represent an exclusive opportunity to exchange ideas on trends in the BFSI sector & global best practices. The summit itself remains as an excellent platform to meet the industry thought leaders and key decision makers. I take this opportunity to specially thank our line-up of distinguished speakers for sparing their time to be here with us today. I would also like to extend a warm welcome to all