Austria by Geoffrey W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report for Austria– Questionnaire Related the Administration Control

ADMINISTRATIVE JUSTICE IN EUROPE – Report for Austria– Questionnaire related the administration control list and typology in the 25 Member States of the European Union Preliminary. 1. Administration jurisdictional control was one typical concern of the liberal streams in the 19th century. In Austria, “the Reichsgericht”, a precursor of the Constitutional Court, was created by the December 1867 constitution which also planned creation of a Supreme Administrative Court (hereafter “the Verwaltungsgerichtshof”). However, this project was only fulfilled in 1876. Following this, the Verwaltungsgerichtshof played a decisive role in developing the legal protection system in Austria, establishing fundamental principles for administrative procedural law. Between 1934 and 1938, the Constitutional Court and the Verwaltungsgerichtshof merged to become “the Bundesgerichtshof”. Several judges were retired for political reasons. The introductions of Chambers with extended composition and of actions for administrative failure to act were significant reforms. After 1938, “the Bundesgerichtshof” lost its authority as Constitutional Court as well as several of its administrative jurisdiction authorities. Several judges were retired for political reasons. In 1940 “the Bundesgerichtshof” became “the Verwaltungsgerichtshof in Vienna” which was an administrative authority of the Reich. In 1941, the Verwaltungsgerichtshof became the “Vienna Außensenat” of the “Reichsverwaltungsgericht” by forming an organisational association with other German administrative courts. A few weeks after the Austrian declaration of independence in 1945, Chancellor Renner commissioned Mr. Coreth to revive the Verwaltungsgerichtshof which took up its duties again on 7th December 1945. The legal text on the Verwaltungsgerichtshof was amended and reissued several times but, in substance, it is still in force today. In 1945, the Constitutional Court was re-established with the same capacities as 1933 and it began carrying out its duties again in 1946. -

Women's and Gender History in Central Eastern Europe, 18Th to 20Th Centuries

Forthcoming in: Irina Livezeanu, Arpad von Klimo (eds), The Routledge History of East Central Europe since 1700 (Routledge 2015) Women‘s and Gender History1 Krassimira Daskalova and Susan Zimmermann Since the 1980s, historians working on East Central Europe, as on other parts of the world, have shown that historical experience has been deeply gendered. This chapter focuses on the modern history of women, and on gender as a category of analysis which helps to make visible and critically interrogate ―the social organization of sexual difference‖2. The new history of women and gender has established, as we hope to demonstrate in this contribution, a number of key insights. First, gender relations are intimately related to power relations. Gender, alongside dominant and non-dominant sexualities, has been invoked persistently to produce or justify asymmetrical and hierarchical arrangements in society and culture as a whole, to restrict the access of women and people identifying with non-normative sexualities to material and cultural goods, and to devalue and marginalize their ways of life. Second, throughout history both equality and difference between women and men have typically resulted in disadvantage for women. Men and women have generally engaged in different socio-cultural, political and economic activities, and this gender-based division of labor, which has itself been subject to historical change, has tended to put women in an inferior position. Even when women and men appeared as equals in one sphere of life, this perceived equality often resulted in drawbacks or an increased burden for women in another area and women‘s contribution was still devalued as compared to men‘s. -

Austria: Vienna

Guide to Catholic-Related Records outside the U.S. about Native Americans See User Guide for help on interpreting entries Archdiocese of Vienna new 2004 AUSTRIA, VIENNA Archdiocese of Vienna Archives AT- 2 A-1010 Wollzeile 2 Wien, Oesterreich Phone 43 1 51552 http://stephanscom.at/ Hours: Monday, Tuesday, and Thursday, 8:30-1:00, 2:00-4:00; and Friday, 8:30-12:00 Access: Some restrictions apply Copying facilities: Yes History of the Leopoldine Society 1827 Bishop Edward D. Fenwick, O.P. of Cincinnati, Ohio sent Reverend John Fréderic Résé to Europe to recruit German- speaking priests and financial assistance for the Cincinnati Diocese; Reverend Samuel Mazzuchelli, O.P. (1806-1864) was among those recruited 1829 In response, the Leopoldine Society (Leopoldinen Stetiftung) was established in Vienna with headquarters at the Augustinian monastery; it solicited German- speaking priests and financial assistance from the dioceses of the Austrian Empire for needy dioceses in the United States, some of which had American Indian missions 1830-1910 The Leopoldine Society donated about $680,500 (3,402,000 kronen) to U.S. dioceses; those with Indian missions that received notable funding included Boise, Cincinnati, Detroit, Grand Rapids, Green Bay, Lead (later renamed Rapid City), Marquette, Nesqually (later renamed Seattle), Oregon (later renamed Portland in Oregon), and Tucson Before 1850 Due to efforts by the Leopoldine Society, several priests from the Austrian Empire emigrated to the United States; those who became missionaries to American Indians include Reverend Frederic I. Baraga (first bishop of the Diocese of Marquette, Michigan), Reverend Joseph F. Buh, Reverend Ignatius Mrak (second bishop of the Diocese of Marquette, Michigan), Reverend Francis Pierz, and Reverend Otto Skolla, O.F.M. -

VIENNA Gets High Marks

city, transformed Why VIENNA gets high marks Dr. Eugen Antalovsky Jana Löw years city, transformed VIENNA 1 Why VIENNA gets high marks Dr. Eugen Antalovsky Jana Löw Why Vienna gets high marks © European Investment Bank, 2019. All rights reserved. All questions on rights and licensing should be addressed to [email protected] The findings, interpretations and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Investment Bank. Get our e-newsletter at www.eib.org/sign-up pdf: QH-06-18-217-EN-N ISBN 978-92-861-3870-6 doi:10.2867/9448 eBook: QH-06-18-217-EN-E ISBN 978-92-861-3874-4 doi:10.2867/28061 4 city, transformed VIENNA Austria’s capital transformed from a peripheral, declining outpost of the Cold War to a city that consistently ranks top of global quality of life surveys. Here’s how Vienna turned a series of major economic and geopolitical challenges to its advantage. Introduction In the mid-1980s, when Vienna presented its first urban development plan, the city government expected the population to decline and foresaw serious challenges for its urban economy. However, geopolitical transformations prompted a fresh wave of immigration to Vienna, so the city needed to adapt fast and develop new initiatives. A new spirit of urban development emerged. Vienna’s remarkable migration-driven growth took place in three phases: • first, the population grew rapidly between 1989 and 1993 • then it grew again between 2000 and 2006 • and finally from 2010 until today the population has been growing steadily and swiftly, by on average around 22,000 people per year • This means an addition of nearly 350,000 inhabitants since 1989. -

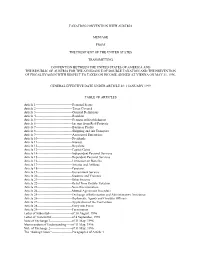

Taxation Convention with Austria Message from The

TAXATION CONVENTION WITH AUSTRIA MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING CONVENTION BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE REPUBLIC OF AUSTRIA FOR THE AVOIDANCE OF DOUBLE TAXATION AND THE PREVENTION OF FISCAL EVASION WITH RESPECT TO TAXES ON INCOME, SIGNED AT VIENNA ON MAY 31, 1996. GENERAL EFFECTIVE DATE UNDER ARTICLE 28: 1 JANUARY 1999 TABLE OF ARTICLES Article 1----------------------------------Personal Scope Article 2----------------------------------Taxes Covered Article 3----------------------------------General Definitions Article 4----------------------------------Resident Article 5----------------------------------Permanent Establishment Article 6----------------------------------Income from Real Property Article 7----------------------------------Business Profits Article 8----------------------------------Shipping and Air Transport Article 9----------------------------------Associated Enterprises Article 10--------------------------------Dividends Article 11--------------------------------Interest Article 12--------------------------------Royalties Article 13--------------------------------Capital Gains Article 14--------------------------------Independent Personal Services Article 15--------------------------------Dependent Personal Services Article 16--------------------------------Limitation on Benefits Article 17--------------------------------Artistes and Athletes Article 18--------------------------------Pensions Article 19--------------------------------Government Service Article 20--------------------------------Students -

Novi-Sad 2021 Bid Book

CREDITS Published by City of Novi Sad Mayor: Miloš Vučević City Minister of Culutre: Vanja Vučenović Project Team Chairman: Momčilo Bajac, PhD Project Team Members: Uroš Ristić, M.Sc Dragan Marković, M.Sc Marko Paunović, MA Design: Nada Božić Logo Design: Studio Trkulja Photo Credits: Martin Candir KCNS photo team EXIT photo team Candidacy Support: Jelena Stevanović Vuk Radulović Aleksandra Stajić Milica Vukadinović Vladimir Radmanović TABLE OF CONTENT 7 BASIC PRINCIPLES 7 Introducing Novi Sad 9 Why does your city wish to take part in the I competition for the title of European Capital of CONTRIBUTION TO THE Culture? LONG-TERM STRATEGY 14 Does your city plan to involve its surrounding 20 area? Explain this choice. Describe the cultural strategy that is in place in your city at the Explain the concept of the programme which 20 18 time of the application, as well as the city’s plans to strengthen would be launched if the city designated as the capacity of the cultural and creative sectors, including European Capital of Culture through the development of long term links between these sectors and the economic and social sectors in your city. What are the plans for sustaining the cultural activities beyond the year of the title? How is the European Capital of Culture action included in this strategy? 24 If your city is awarded the title of Europian Capital of Culture, II what do you think would be the long-term cultural, social and economic impact on the city (including in terms of urban EUROPEAN development)? DIMENSION 28 25 Describe your plans for monitoring and evaluating the impact of the title on your city and for disseminating the results of the evaluation. -

Low Fertility in Austria and the Czech Republic: Gradual Policy Adjustments

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Sobotka, Tomáš Working Paper Low fertility in Austria and the Czech Republic: Gradual policy adjustments Vienna Institute of Demography Working Papers, No. 2/2015 Provided in Cooperation with: Vienna Institute of Demography (VID), Austrian Academy of Sciences Suggested Citation: Sobotka, Tomáš (2015) : Low fertility in Austria and the Czech Republic: Gradual policy adjustments, Vienna Institute of Demography Working Papers, No. 2/2015, Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW), Vienna Institute of Demography (VID), Vienna This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/110987 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten -

Open Government Data Austria - Organisation, Procedures and Uptake

Open Government Data Austria - Organisation, Procedures and Uptake Johann Höchtl, Peter Parycek, Center for EGovernance, Danube University Krems, Dr. KarlDorrekStraße 30, 3500 Krems, Austria. {johann.hoechtl|peter.parycek}@donauuni.ac.at Brigitte Lutz, Office of the CIO City of Vienna, Rathausstraße 8, 1010 Vienna, Austria. [email protected] Stefan Pawel, City of Linz, project manager of OPEN COMMONS_LINZ, Gruberstraße 42, 4020 Linz, Austria. [email protected] Abstract. Open Government Data in Austria is characterized by a collaboration of the willing and capable, as well as direct community involvement which happens at various levels along the data publication line. Early and direct community involvement is regarded as one substantial key success factor of OGD in Austria. This paper describes some of the noteworthy measures to spark open data usage as well as first visible effects of changed administrative and external processes and procedures since the inception of OGD. Organisation of Open Government Data in Austria Unlike the administrations of the UK, the USA or France, there is no proactive freedom of information law which would govern the release of Open Government Data (OGD) in Austria. At the time when the EU directive on the reuse of public sector information of 2003 got implemented into national law, no single portal provided access to information of the public administration. In short, when the OGD movement was brought from bottomup to the administration, no good practice was in place how legally or organisationalwise should be dealt with requests for data. While there is a longlasting tradition in Austria of legally framed eGovernment, concerns were raised that for OGD to be effective, a much faster pace of development and less formalisation than currently would be necessary. -

Global Austria Austria’S Place in Europe and the World

Global Austria Austria’s Place in Europe and the World Günter Bischof, Fritz Plasser (Eds.) Anton Pelinka, Alexander Smith, Guest Editors CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | Volume 20 innsbruck university press Copyright ©2011 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, ED 210, 2000 Lakeshore Drive, New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Book design: Lindsay Maples Cover cartoon by Ironimus (1992) provided by the archives of Die Presse in Vienna and permission to publish granted by Gustav Peichl. Published in North America by Published in Europe by University of New Orleans Press Innsbruck University Press ISBN 978-1-60801-062-2 ISBN 978-3-9028112-0-2 Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Fritz Plasser, Universität Innsbruck Production Editor Copy Editor Bill Lavender Lindsay Maples University of New Orleans University of New Orleans Executive Editors Klaus Frantz, Universität Innsbruck Susan Krantz, University of New Orleans Advisory Board Siegfried Beer Helmut Konrad Universität Graz Universität -

Boznia and Herzegovina

Grids & Datums BOZNIA AND HERZEGOVINA by Clifford J. Mugnier, C.P., C.M.S. “The region’s ancient inhabitants were Illyrians, followed by the Ro- Austria-Hungarians pushed Bosnia and Herzegovina into the modern mans who settled around the mineral springs at Ilidža near Sarajevo in age with industrialization, the development of coal mining and the 9AD. When the Roman Empire was divided in 395AD, the Drina River, building of railways and infrastructure. Ivo Andric´ ’s Bridge over the today the border with Serbia, became the line dividing the Western Drina succinctly describes these changes in the town of Višegrad. But Roman Empire from Byzantium. The Slavs arrived in the late 6th and political unrest was on the rise. Previously, Bosnian Muslims, Catholics early 7th centuries. In 960 the region became independent of Serbia, and Orthodox Christians had only differentiated themselves from each only to pass through the hands of other conquerors: Croatia (PE&RS, other in terms of religion. But with the rise of nationalism in the mid- July 2012), Byzantium, Duklja (modern-day Montenegro) and Hungary 19th century, Bosnia’s Catholic and Orthodox population started to (PE&RS, April 1999). Bosnia’s medieval history is a much-debated identify themselves with neighboring Croatia or Serbia respectively. subject, mainly because different groups have tried to claim authen- At the same time, resentment against foreign occupation intensified ticity and territorial rights on the basis of their interpretation of the and young people across the sectarian divide started cooperating with country’s religious make-up before the arrival of the Turks. -

Austrian Federalism in Comparative Perspective

CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 24 Bischof, Karlhofer (Eds.), Williamson (Guest Ed.) • 1914: Aus tria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I War of World the Origins, and First Year tria-Hungary, Austrian Federalism in Comparative Perspective Günter Bischof AustrianFerdinand Federalism Karlhofer (Eds.) in Comparative Perspective Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) UNO UNO PRESS innsbruck university press UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Austrian Federalism in ŽŵƉĂƌĂƟǀĞWĞƌƐƉĞĐƟǀĞ Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 24 UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Copyright © 2015 by University of New Orleans Press All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage nd retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive. New Orleans, LA, 70148, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America Book design by Allison Reu and Alex Dimeff Cover photo © Parlamentsdirektion Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press by Innsbruck University Press ISBN: 9781608011124 ISBN: 9783902936691 UNO PRESS Publication of this volume has been made possible through generous grants from the the Federal Ministry for Europe, Integration, and Foreign Affairs in Vienna through the Austrian Cultural Forum in New York, as well as the Federal Ministry of Economics, Science, and Research through the Austrian Academic Exchange Service (ÖAAD). The Austrian Marshall Plan Anniversary Foundation in Vienna has been very generous in supporting Center Austria: The Austrian Marshall Plan Center for European Studies at the University of New Orleans and its publications series. -

Austria-Czech Republic

INTERREG II Austria/Czech Republic Austria-Czech Republic Examples of projects ¡ Vienna Centre for business co-operation Interreg II is helping finance a feasibility study on whether, and if so, under what conditions, a East-West Business Centre (EBC) may be able to assist small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Vienna and the bor- dering regions of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia to compete more successfully in international markets, by supporting research and development pilot actions and technology transfer and innovative activities. ¡ Eligible Areas The project is structured into four, partially overlapping Austria: Mühlviertel, Waldviertel, Weinviertel stages. Interreg is co-funding the first two stages, which Vienna focus on a series of workshops designed to bring together all relevant partners, and the development of initial plan- ¡ Financing ning strategies on the viability of an eventual Vienna- Total cost: (1995 prices) 12.114 million euro based EBC. It is anticipated that at the end of these initial EU contribution: 4.5 million euro phases, a basis will be provided for a definite decision to be taken on whether to establish the Centre and, if so, ¡ Areas of Intervention how to proceed. One essential element of the project is Improvement of infrastructure 7 % the emphasis placed on tracking its progress: it is evaluat- Economy, tourism and socio-cultural co-operation 69.3% ed at short intervals in order to determine how best the Agriculture and forestry 6.9% next stage should be implemented. Human resources 5.4% ¡ Spatial planning, regional policy VITECC project and technical assistance 11.4% The Vienna Tele Cooperation Centre (VITECC) is a service network using modern communication technology to sup- port and advance interurban co-operation across the EU outside border.