Sources of Altruistic Calling in Orthodox Jewish Communities: a Grounded Theory Ethnography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Politics, Presidential Contest Loom Large at AIPAC

HEADLINES | 8 SPECIAL SECTION | 15 GRAPPLING WITH SENIOR LIFESTYLE INFERTILITY Developing empathy, A film hits home for staying active and local Jewish group getting screened MARCH 6, 2020 | ADAR 10, 5780 | VOLUME 72, NUMBER 12 $1.50 Neo-Nazis target editor Politics, presidential contest of Jewish publication loom large at AIPAC ELLEN O’BRIEN | STAFF WRITER JACKSON RICHMAN AND HEATHER ROBINSON | JNS.ORG TOBY TABACHNICK | CONTRIBUTING WRITER n Arizona man associated with a neo-Nazi group was among Afour arrested on Wednesday, Feb. 26, and charged with ona Kaufman had never been to an AIPAC Policy conspiracy to threaten and intimidate Mala Blomquist, the editor RConference. But for the Duquesne University of Arizona Jewish Life, and an unnamed member of the Arizona School of Law professor from Pennsylvania, this was Association of Black Journalists. an important year to travel to the nation’s capital All four charged are affiliated with Atomwaffen Division, a and be among 18,000 supporters of the pro-Israel small neo-Nazi group that became active in 2016, according to lobbying group. the Anti-Defamation League. The group’s members “are prepar- “I’m aware, especially right now, that there is a little ing for a race war to combat what they consider the cultural and bit more controversy about Israel than I recognized or racial displacement of the white race,” reported the ADL. The noticed in the past,” said Kaufman. “So to the extent group’s propaganda includes references to Charles Manson and that it is more important that we are showing that we Nazi iconography. -

Shabbat Ki Teitzei B”H

Shabbat Ki Teitzei B”H Friday, September 13th, 2019 14 Elul, 5779 Candle lighting 6.:50 PM KIDDISH: Kiddish is sponsered by Benyomin and Leiba Simon in honor of Benyomin's Mincha at 7:00PM birthday. JUNIOR CONGREGATOIN: For the new year begins this Shabbat and we are excited to have expanded to 3 groups; Shabbat Services Tanya/soul maps 8:30 AM - Children through Grade 3, upstairs, with Mrs. Dina Klapper Shacharit 9:00 AM - Girls, Grades 4 and up, downstairs classroom on right, led by Aviva Laskin and Bella Rudoy, Mincha 6:50 PM originally Junior Congregants themselves. Shabbat Ends 7:48 PM - Boys, Grades 4 and up, downstairs library on left, led by a rotation of fathers and a student rabbi. Havdalah Service/Living Torah DVD Feel free to email [email protected] if you'd like to discuss anything. of the Rebbe 7:48 PM JOIN US FOR THE HIGH HOLIDAYS!!: If you will be away for the High Holidays and Daven with us all year, please consider sponsoring a seat for someone who can not afford. Chabad of Junior Congregation Riverdale offers a unique style of services which uplift and renew the spirit! Seats are now available 10:45 am - 12 pm online at ChabadBronx.org/Holidays/High Holiday Reservations. PreK-Grade 3 (upstairs) - Mrs. Dina Klapper SHOFAR FACTORY: Sunday, September 22, 2019 11:00 am—1:00 pm. See flyer for detail. Grades 4+ Girls (downstairs) - Aviva Laskin & Maya Rudoy HAVE YOUR MEZUZOT AND TEFILLIN: checked by Rabbi Feitel Lewin (the scribe) Sunday, Grade 4+ Boys (downstairs September 22nd at Chabad of Riverdale.day from 9:30am -2pm. -

Rabbi Eliezer Levin, ?"YT: Mussar Personified RABBI YOSEF C

il1lj:' .N1'lN1N1' invites you to join us in paying tribute to the memory of ,,,.. SAMUEL AND RENEE REICHMANN n·y Through their renowned benevolence and generosity they have nobly benefited the Torah community at large and have strengthened and sustained Yeshiva Yesodei Hatorah here in Toronto. Their legendary accomplishments have earned the respect and gratitude of all those whose lives they have touched. Special Honorees Rabbi Menachem Adler Mr. & Mrs. Menachem Wagner AVODASHAKODfSHAWARD MESORES A VOS AW ARD RESERVE YOUR AD IN OUR TRIBUTE DINNER JOURNAL Tribute Dinner to be held June 3, 1992 Diamond Page $50,000 Platinum Page $36, 000 Gold Page $25,000 Silver Page $18,000 Bronze Page $10,000 Parchment $ 5,000 Tribute Page $3,600 Half Page $500 Memoriam Page '$2,500 Quarter Page $250 Chai Page $1,800 Greeting $180 Full Page $1,000 Advertising Deadline is May 1. 1992 Mall or fax ad copy to: REICHMANN ENDOWMENT FUND FOR YYH 77 Glen Rush Boulevard, Toronto, Ontario M5N 2T8 (416) 787-1101 or Fax (416) 787-9044 GRATITUDE TO THE PAST + CONFIDENCE IN THE FUTURE THEIEWISH ()BSERVER THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN) 0021 -6615 is published monthly except July and August by theAgudath Israel of America, 84 William Street, New York, N.Y. 10038. Second class postage paid in New York, N.Y. LESSONS IN AN ERA OF RAPID CHANGE Subscription $22.00 per year; two years, $36.00; three years, $48.00. Outside of the United States (US funds drawn on a US bank only) $1 O.00 6 surcharge per year. -

2016-2017 Guide to Jewish Living 1 2 2016-2017 Guide to Jewish Living 2016-2017 Guide to Jewish Living 3

2016-2017 Guide to Jewish Living 1 2 2016-2017 Guide to Jewish Living 2016-2017 Guide to Jewish Living 3 AT A GLANCE Chapter 1: Chapter 4: JEWISH LEARNING RELIGIOUS LIFE 6 – 17 38 – 41 Chapter 2: Chapter 5: COMMUNITY RESOURCES ACTIVITIES & VOLUNTEERING 18 – 24 42 – 48 Chapter 3: Chapter 6: SYNAGOGUES & CONGREGATIONS FOOD & FUN 26 – 36 50 – 55 INDEX OF GUIDE ENTRIES: 56 – 57 INDEX OF ADVERTISERS: 58 4 2016-2017 Guide to Jewish Living 2016-2017 Guide to Jewish Living 5 The Jewish Voice’s 2016-2017 Guide to Jewish Dear Friends, Living is a directory of all things Jewish in Welcome to the 2016-2017 Guide to Jewish the Rhode Island community, a voice for our Living. Whether you are new to the area or advertisers and us. It’s a comprehensive listing you’ve been here for years, this guide will help of the programs and resources available in our you find everything Jewish in greater Rhode area. And it’s a showcase for the advertisers Island. that support them. Each organization, program, service, and We hope you, our readers, will turn to the resource is part of a beautiful mosaic that guide when you need a resource. And please supports quality Jewish living. Use this guide support the advertisers in the 2016-2017 Guide regularly to discover all that our community to Jewish Living by letting them know you has to offer. In the meantime, we at the Jewish saw their ad and rewarding them with your Alliance look forward to seeing you at the business. -

Rjc Bulletin

ויחי RJC BULLETIN Parshat December 21 – December 28, 2018 י‘ד טבת— כ‘ טבת Candle Lighting December 21, 2018 4:13 PM Havdalah December 22, 2018 5:13 PM 14 Tevet– 20 Tevet 5779 RJC Membership Renewal is Happening Now MAZAL TOV Mazal Tov to Dr. Jonathan and Rena Boniuk on The RJC Membership Committee has launched the the upcoming marriage of their son Yoseph to Adira 2019 Membership Drive and Renewal. Koppel, daughter of Dr. Robert and Tammy Koppel Visit rjconline.org/membership.html to renew your membership for 2019 today! of West Hempstead. Mazal Tov to the grandparents, Dr. Irving and Sarah Listowsky, Isabel Boniuk, Rabbi Fabian Schonfeld, and Mrs. Vera SHIURIM THIS SHABBAT RJC CHOLENT COOK-OFF RECAP Koppel. Mazal Tov to Yoseph's siblings Gavriel, Rabbi Drelich's Shabbat Parsha and Thank you to our RJC amazing volunteers who Josh, & Rivka and the entire family. Talmud Macot Shiur will follow the 7:00AM helped make our Cholent Cook-off a wonderful minyan Kiddush. event: Mazal Tov to Shira and Zach Baratz and big sis- Melissa Arnold, Brenda Ben-Zaken, Stacey Daube, ter, Zoe, on the birth of a baby boy. Hashkama Shiur Naomi Dorfman, Debbie Drelich, Faith Feder, Rabbi Charles Sheer's shiur will take place Melanie Finkel, Rabbi Yitzi Genack, Adina Haller, Mazel Tov Dana & Josh Jerusalmi and big sister, after the Hashkama kiddush in room 201. The Sima Horowitz, Alyssa Herman-Kronisch, Marcella Ava, on the birth of a baby girl, Lyla Emilia. topic is “A T’shuva of the Havvot Yair regard- Marcus, Sandra Molinas, Vivian Neiss, Donna Salamon, Hannah Shapiro, Barbara Sopher, ing a Father’s Will that His Daughter Should Recite Kaddish in His Memory—Part II.” Deena Spinder, Rhonda Stober, and Susan Tessel. -

Congregation Ohr Torah

Congregation Ohr Torah Weekly Announcements http://www.ohrtorah.net 48 Edgemount Road Edison, NJ 08817 Rabbi Yaakov Luban – Rabbi Jeff Klein - President Rabbi Sariel Malitzky – Assistant Rabbi Parshat Chayei Sarah/Mevarchim 25 Cheshvan 5779 November 3, 2018 Candlelighting: 5:34PM MAZEL TOV The Infamous Dreyfus Affair. The video Mincha: 5:40 PM …to Miriam and David Hanfling on details the travesty which exposed the Shacharis: 7:45 & 9 AM granddaughter Frumie Rajchgod ignorance and prejudice of a nation in France Rabbi Hoffman’s Halacha B’iyun Shiur after becoming a Kallah. Mazel Tov to Frumie's in 1895. See how high-ranking officers set Hashkama up Dreyfus to take the blame for a critical Sof Z’man Krias Shma (GR”A): 10:10 AM parents Rabbi Tzvi and Deena Rajchgod, Rabbi Luban’s Moed Katan Shiur –4:35 PM to the Chosen, Shabsi and parents, Uri and security leak. An absolutely great movie! Mincha: 1:45 PM & 5:25 PM Judy Aqua and Family of New Rochelle, and Introduction by Henry Schanzer D’var Torah Shalosh Seudos speaker: Rabbi Malitzky to extended Rajchgod, Hanfling, Lehman and by Mike Samel Date: Tues. Nov 13, Time Kavesh families. Special Mazel Tov to Bubby Noon At Ohr Torah Cost for lunch $12.00 Maariv: 6:35 PM Kagan. RSVP by Nov 9th to Bella Shabbos Ends: 6:42 PM …to Fay and David Moskovic on the birth of [email protected] or 732 3171786 or MOVE CLOCKS BACK ONE HOUR a son to their chidren Dr Sheemon and Mildred 732 572 1712 or Marcia 732 572 Weekday Shacharis: 5998 Sun. -

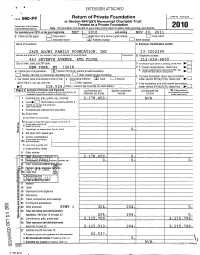

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

d I EXTENSION ATTACHED Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2010 Internal Revenue Service Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. For calendar year 2010 , or tax year beginning DEC 1, 2010 and ending NOV 3 0, 2011 G Check all that apply. Initial return Initial return of a former public charity Ej Final return 0 Amended return ® Address chanae Name change Name of foundation A Employer identification number JACK ADJMI FAMILY FOUNDATION INC 13-3202295 Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/swte B Telephone number 463 SEVENTH AVENUE , 4TH FLOOR 212-629-960 0 City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here NEW YORK , NY 10 018 D 1- Foreign organizations, check here 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, H Check type of organization: Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation check here and attach computation charitable Other taxable foundation Section 4947(a )( 1 ) nonexem pt trust 0 private E If p rivate foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: ® Cash 0 Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part ll, col. (c), line 16) = Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination 111114 218 5 2 4 . (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis.) under section 507 b 1 B , check here Part I Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net ( d) Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns (b) (c), and (d) may not for charitable purposes necessarily equal the amounts in column (a)) expenses per books income income (cash basis only) 1 Contributions, gifts, grants, etc., received 2 , 178 , 450. -

Denver Tourist Guide

Denver Jewish Tourist Guide a project of Contents Welcome to Denver......2 Shul/Minyanim Listing......3 Kosher Food in Denver......4 Directory of Jewish Amenities in Denver......6 1 Denver Jewish Tourist Guide Welcome to the Mile High City! We hope you enjoy your stay in Denver, CO. The Denver Jewish community is unique in that it is has a full Jewish infrastructure including Torah day schools, Yeshiva and Bais Yaakov high schools, kosher eateries and groceries, shuls, and mikvaos, while retaining that special out-of- town feel. The Denver Jewish community is also unique in that there are different areas where the Jewish community is concentrated, with the main communities centered in West Denver, East Denver, and Southeast Denver/Greenwood Village. In addition, there is a Jewish Bucharian community in Aurora, Colorado. While there is no shortage of activities for vacationing Torah families to enjoy in Denver and the surrounding areas, both indoors and especially outdoors, this tourist guide is not meant to provide information on what to do while in Denver. Rather, this guide seeks to provide information regarding Jewish amenities in Colorado, such as shul/minyan info, kosher food info and the like. This guide was created by the Denver Community Kollel. The Kollel was founded in 1998 with the mission of bringing Torah learning, Torah teaching and Torah living to Denver Jewry. We invite you to come learn in one of our two batei medrash during your stay here in Denver. These batei medrash are accessible at all times of day; for more information on accessing them, contact the Kollel office at 303-820-2855 or email [email protected]. -

Terumah February 8-9, 2019 4 Adar I 5779 SHABBAT TIMES This Week’S Announcements Are Sponsored by Lamdeinu

CONGREGATION BETH AARON ANNOUNCEMENTS Parshat Terumah February 8-9, 2019 4 Adar I 5779 SHABBAT TIMES This week’s announcements are sponsored by Lamdeinu. For information on their schedule of classes, see page 4 and go to lamdeinu.org. Friday, February 8 Study in depth; be inspired! Latest Candles: 5:03 p.m. Mincha/Kabbalat Shabbat: 5:05 p.m. SCHEDULE FOR THE WEEK OF FEBRUARY 10 Shabbat, February 9 Sun Mon Tues Wed Thu Fri Hashkama Minyan: 7:30 a.m. 10 11 12 13 14 15 Nach shiur: 8:20 a.m. Main Minyan: 8:45 a.m. Earliest Tallit 5:57 5:56 5:55 5:54 5:52 5:51 Youth Minyan: 9:15 a.m. Shacharit 6:30 MS 5:45 SH 5:55 SH 5:55 SH 5:41 SH 5:55 SH Sof Zman Kriat Shema: 9:34 a.m. 7:15 MS 6:20 BM 6:30 BM 6:30 BM 6:20 BM 6:30 BM Early Mincha: 1:45 p.m. 8:00 MS 7:10 BM 7:15 BM 7:15 BM 7:10 BM 7:15 BM Daf Yomi: 3:45 p.m. 8:45 MS 8:00 BM 8:00 BM 8:00 BM 8:00 BM 8:00 BM Women’s Learning: 3:45 p.m., in the shul Mincha 1:00 BM Social Hall, Shmuel Bet, Chapter 21, led by Rivka Herzfeld and Mollie Fisch Mincha/ 5:10 MS 5:10 BM 5:10 MS 5:10 BM 5:10 BM 5:15 MS 5th/6th grade Boys’ Mishna Group: Maariv 4:25 p.m., in the Book Room Maariv Mincha: 4:55 p.m., followed by Rabbi 8:00 BM 8:00 BM 8:00 BM 8:00 BM 8:00 BM Rothwachs’ shiur, “The What, When, 9:30 BM 9:30 BM 9:30 BM 9:30 BM 9:30 BM Who, and How of Correcting a Ba’al KEY: MS = Main Shul BM = Beit Midrash SH = Social Hall Koreh (Part 1)” MAZAL TOV TO Maariv: 6:03 p.m. -

The Path to Follow Mishpatim 376 a Hevrat Pinto Publication

The Path To Follow Mishpatim 376 A Hevrat Pinto Publication Under the Direction of Rabbi David H. Pinto Shlita www.hevratpinto.org | [email protected] th th Editor-in-Chief: Hanania Soussan Shvat 24 5771 - January 29 2011 32 rue du Plateau 75019 Paris, France • Tel: +331 48 03 53 89 • Fax: +331 42 06 00 33 Rabbi David Pinto Shlita The Principles Of The Fear Of Heaven is written, “Ve’eleh [And these] are the ordinances that you shall place He Will Eventually Return before them” (Shemot 21:1). Rashi explains: “Wherever eleh [these] is This is what Rashi is alluding to by saying that ve’eleh adds to what was previously used, it replaces what was previously stated; ve’eleh [and these] adds to stated. That is, just as the previous laws were given on Sinai, these were also given what was previously stated. Just as what was previously stated was from on Sinai, meaning that a person must not say: “I will fulfill the 613 mitzvot given by Sinai, these were also from Sinai.” In reality, how could anything think of G-d, but I won’t bother with the fences that the Sages added to the Torah mitzvot.” Itnot observing the social laws, even if they were not given on Sinai? In fact why does Just as it is a person’s duty to fulfill the mitzvot written in the Torah, it is also his the Torah need to tell us that just as the other laws were given on Sinai, these were duty to fulfill the decrees of the Sages, which were also given to Moshe on Sinai. -

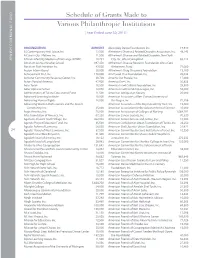

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2015 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. 19,930 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 12,500 Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Disorders Association, Inc. 46,245 A Cure in Our Lifetime, Inc. 11,500 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, New York A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 20,731 City, Inc. d/b/a CaringKind 65,215 Abraham Joshua Heschel School 397,450 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation d/b/a Cure JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Path Initiative, Inc. 42,500 Alzheimer’s Fund 71,000 Accion International 30,000 Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 15,100 Achievement First, Inc. 170,000 Am Yisroel Chai Foundation, Inc. 25,036 Achiezer Community Resource Center, Inc. 20,728 Ameinu Our People, Inc. 17,000 Actors Fund of America 47,900 America Gives, Inc. 30,856 Adas Torah 16,500 America-Israel Cultural Foundation, Inc. 25,500 Adler Aphasia Center 14,050 America-Israel Friendship League, Inc. 55,000 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 11,500 American Antiquarian Society 25,000 Advanced Learning Institute 10,000 American Associates of Ben-Gurion University of Advancing Human Rights 18,000 the Negev, Inc. 71,386 Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, Inc. 15,000 Community, Inc. 25,000 American Association for the Advancement of Science 35,000 Aegis America, Inc. 75,000 American Association of Colleges of Nursing 1,064,797 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 67,250 American Cancer Society, Inc. -

Controlling Anger

CONTROLLING ANGER o enjoy harmonious relationships with one’s spouse, family, friends, and Tprofessional associates is a universal human goal. Anger, however, is a character trait that can undermine this basic aspiration. Anger can destroy years of investment in a relationship in a matter of minutes. So why is it that many people are quite content to live with the tendency to become angry? The answer is that many people go through life without ever thinking how destructive anger really is, and conversely, how constructive patience is. And even if someone has this understanding, he may lack practical techniques to control anger. This class will analyze why anger is so destructive and provide insights and tools to help us gain control in the most trying moments. This class will address the following questions: What makes an angry person so frightening to other people? What does an angry person stand to lose and a patient person stand to gain? How does one replace anger with patience? Isn’t it appropriate to be angry sometimes? Is it really possible to overcome a tendency toward anger? Class Outline Section I. What We Stand to Lose Part A. Personal Damage Part B. Social Damage Part C. Undermining Personal and Spiritual Growth Section II. The Benefits of Patience Section III. Tools for Controlling Anger Part A. Forming Positive Habits Part B. Putting Things in Perspective Part C. Developing Humility Part D. Developing Trust in God 1 Bein Adam L’Chavero CONTROLLING ANGER SECTION I. WHAT WE STAND TO LOSE Anger and frustration – not so common, you say? Just consider the following: A large, international retail corporation is now proudly offering its customers “Frustration-free packaging – no dreaded wire ties, no impenetrable plastic clamshells.” This special wrapping is designed to protect valued customers from becoming victims of “wrap rage,” the fury that sets in when it takes a customer more than a nanosecond to get to his new purchase.