The Congressional Bureaucracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Studies –American History: the Founding Principles, Civics and Economics Course

Appendix A: American History: The Founding Principles, Civics and Economics This appendix contains additions made to the North Carolina Essential Standards for Civics and Economics pursuant to the North Carolina General Assembly passage of The Founding Principles Act (SL 2011-273). This document is organized as follows: an introduction that describes the intent of the course and a set of standards that establishes the expectation of what students should understand, know, and be able to do upon successful completion of the course. There are ten essential standards for this course, each with more specific clarifying objectives. The name of the course has been changed to American History: The Founding Principles, Civics and Economics and the last column has been added to show the alignment of the standards to the Founding Principles Act. 6 North Carolina Essential Standards Social Studies –American History: The Founding Principles, Civics and Economics Course American History: The Founding Principles, Civics and Economics has been developed as a course that provides a framework for understanding the basic tenets of American democracy, practices of American government as established by the United States Constitution, basic concepts of American politics and citizenship and concepts in macro and micro economics and personal finance. The essential standards of this course are organized under three strands – Civics and Government, Personal Financial Literacy and Economics. The Civics and Government strand is framed to develop students’ increased understanding of the institutions of constitutional democracy and the fundamental principles and values upon which they are founded, the skills necessary to participate as effective and responsible citizens and the knowledge of how to use democratic procedures for making decisions and managing conflict. -

The Influence of Jurisprudential Inquiry 1

Running Head: THE INFLUENCE OF JURISPRUDENTIAL INQUIRY 1 The Influence of Jurisprudential Inquiry Learning Strategies and Logical Thinking Ability towards Learning of Civics in Senior High School (SMA) 1Hernawaty Damanik 2I Nyoman S. Degeng 2Punaji Setyosari 2I Wayan Dasna 1Open University; State University of Malang 2State University of Malang Author Note Hernawaty Damanik is senior lecturer at Open University, Malang, and student of Graduate Program in Education Technology State University of Malang. I Nyoman S. Degeng and Punaji Setyosari are professors at Graduate Program State University of Malang. I Wayan Dasna is senior lecturer at Graduate Program State University of Malang Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to [email protected] THE INFLUENCE OF JURISPRUDENTIAL INQUIRY 2 THE INFLUENCE OF JURISPRUDENTIAL INQUIRY LEARNING STRATEGIES AND LOGICAL THINKING ABILITY TOWARDS LEARNING OF CIVICS SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL (SMA) Abstract Pancasila and Citizenship Education (Civics) is one of many other school subjects emphasizing on value and moral education in order to form multicultural Indonesian citizens who appreciate the culture of plural communities. The learning of PPKn (civics) should be designed and developed through a thorough strategy in accordance with its aims and materials to create students with critical, argumentative, and logical thinking ability. The learning of civics has not been totally carried out on the tract where teachers are dominantly active in the class while students just do memorizing and reading, less of joyfull learning, and become “text-bookish”. One of many other strategies to succeed innovative, constructive, and relevant learning in accordance with the thinking ability of Senior High School students is through jurisprudential inquiry. -

NGPF's 2021 State of Financial Education Report

11 ++ 2020-2021 $$ xx %% NGPF’s 2021 State of Financial == Education Report ¢¢ Who Has Access to Financial Education in America Today? In the 2020-2021 school year, nearly 7 out of 10 students across U.S. high schools had access to a standalone Personal Finance course. 2.4M (1 in 5 U.S. high school students) were guaranteed to take the course prior to graduation. GOLD STANDARD GOLD STANDARD (NATIONWIDE) (OUTSIDE GUARANTEE STATES)* In public U.S. high schools, In public U.S. high schools, 1 IN 5 1 IN 9 $$ students were guaranteed to take a students were guaranteed to take a W-4 standalone Personal Finance course standalone Personal Finance course W-4 prior to graduation. prior to graduation. STATE POLICY IMPACTS NATIONWIDE ACCESS (GOLD + SILVER STANDARD) Currently, In public U.S. high schools, = 7 IN = 7 10 states have or are implementing statewide guarantees for a standalone students have access to or are ¢ guaranteed to take a standalone ¢ Personal Finance course for all high school students. North Carolina and Mississippi Personal Finance course prior are currently implementing. to graduation. How states are guaranteeing Personal Finance for their students: In 2018, the Mississippi Department of Education Signed in 2018, North Carolina’s legislation echoes created a 1-year College & Career Readiness (CCR) neighboring state Virginia’s, by which all students take Course for the entering freshman class of the one semester of Economics and one semester of 2018-2019 school year. The course combines Personal Finance. All North Carolina high school one semester of career exploration and college students, beginning with the graduating class of 2024, transition preparation with one semester of will take a 1-year Economics and Personal Finance Personal Finance. -

Learn About the United States Quick Civics Lessons for the Naturalization Test

Learn About the United States Quick Civics Lessons for the Naturalization Test M-638 (rev. 02/19) Learn About the United States: Quick Civics Lessons Thank you for your interest in becoming a citizen of the United States of America. Your decision to apply for IMPORTANT NOTE: On the naturalization test, some U.S. citizenship is a very meaningful demonstration of answers may change because of elections or appointments. your commitment to this country. As you study for the test, make sure that you know the As you prepare for U.S. citizenship, Learn About the United most current answers to these questions. Answer these States: Quick Civics Lessons will help you study for the civics questions with the name of the official who is serving and English portions of the naturalization interview. at the time of your eligibility interview with USCIS. The USCIS Officer will not accept an incorrect answer. There are 100 civics (history and government) questions on the naturalization test. During your naturalization interview, you will be asked up to 10 questions from the list of 100 questions. You must answer correctly 6 of the 10 questions to pass the civics test. More Resources to Help You Study Applicants who are age 65 or older and have been a permanent resident for at least 20 years at the time of Visit the USCIS Citizenship Resource Center at filing the Form N-400, Application for Naturalization, uscis.gov/citizenship to find additional educational are only required to study 20 of the 100 civics test materials. Be sure to look for these helpful study questions for the naturalization test. -

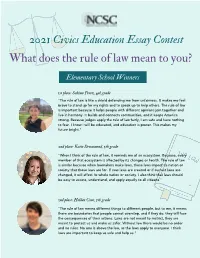

What Does the Rule of Law Mean to You?

2021 Civics Education Essay Contest What does the rule of law mean to you? Elementary School Winners 1st place: Sabina Perez, 4th grade "The rule of law is like a shield defending me from unfairness. It makes me feel brave to stand up for my rights and to speak up to help others. The rule of law is important because it helps people with different opinions join together and live in harmony. It builds and connects communities, and it keeps America strong. Because judges apply the rule of law fairly, I am safe and have nothing to fear. I know I will be educated, and education is power. This makes my future bright." 2nd place: Katie Drummond, 5th grade "When I think of the rule of law, it reminds me of an ecosystem. Because, every member of that ecosystem is affected by its changes or health. The rule of law is similar because when lawmakers make laws, those laws impact its nation or society that those laws are for. If new laws are created or if current laws are changed, it will affect its whole nation or society. I also think that laws should be easy to access, understand, and apply equally to all citizens." 3nd place: Holden Cone, 5th grade "The rule of law means different things to different people, but to me, it means there are boundaries that people cannot overstep, and if they do, they will face the consequences of their actions. Laws are not meant to restrict, they are meant to protect us and make us safer. -

Impeachment on a Page

Impeachment on a Page Whistleblower Complaint “In the course of my official duties, I have received information from multiple U.S. Government officials that the President of the United States is using the power of his office to solicit interference from a foreign country in the 2020 U.S. election” Chairman Schiff outlines the 4 questions of his investigation 1. Did Trump seek foreign assistance for an election? 3. Was military assistance withheld until confirmation that the investigation would occur? 2. Was the meeting sought by the Ukrainian government conditioned on the Ukraine investigation of Vice President Biden and his son? 4. Were these issues covered up by the Trump administration? Headlines from Testimony to House Investigators “Joseph Maguire defends his handling of the “Kent told investigators he was cut out of Ukraine whistleblower complaint involving President policymaking after May meeting with Chief of Staff Mick Joseph Maguire Trump” – Fox News George Kent Mulvaney” – New York Times Acting Director of National Deputy Assitant Secretary Intelligence of State Testified September 25-26 Testified October 15th “Volker depicts Giuliani as the driving force “Sondland testifies that Trump directed diplomats to work behind an effort to get Ukraine to investigate Joe with Giuliani on Ukraine” – CNN Kurt Volker and Hunter Biden” – CBS News Gordon Sondland Former U.S. Special Envoy U.S. Ambassador to the to Ukraine European Union Testified October 3rd Testified: October 17th “McKinley told House investigators that he quit his job -

NGPF's 2021 State of Financial Education Report

11 ++ 2020-2021 $$ xx %% NGPF’s 2021 State of Financial == Education Report ¢¢ Who Has Access to Financial Education in America Today? In the 2020-2021 school year, nearly 7 out of 10 students across U.S. high schools had access to a standalone Personal Finance course. 2.4M (1 in 5 U.S. high school students) were guaranteed to take the course prior to graduation. GOLD STANDARD GOLD STANDARD (NATIONWIDE) (OUTSIDE GUARANTEE STATES)* In public U.S. high schools, In public U.S. high schools, 1 IN 5 1 IN 9 $$ students were guaranteed to take a students were guaranteed to take a W-4 standalone Personal Finance course standalone Personal Finance course W-4 prior to graduation. prior to graduation. STATE POLICY IMPACTS NATIONWIDE ACCESS (GOLD + SILVER STANDARD) Currently, In public U.S. high schools, = 7 IN = 7 10 states have or are implementing statewide guarantees for a standalone students have access to or are ¢ guaranteed to take a standalone ¢ Personal Finance course for all high school students. North Carolina and Mississippi Personal Finance course prior are currently implementing. to graduation. How states are guaranteeing Personal Finance for their students: In 2018, the Mississippi Department of Education Signed in 2018, North Carolina’s legislation echoes created a 1-year College & Career Readiness (CCR) neighboring state Virginia’s, by which all students take Course for the entering freshman class of the one semester of Economics and one semester of 2018-2019 school year. The course combines Personal Finance. All North Carolina high school one semester of career exploration and college students, beginning with the graduating class of 2024, transition preparation with one semester of will take a 1-year Economics and Personal Finance Personal Finance. -

"Public Service Must Begin at Home": the Lawyer As Civics Teacher in Everyday Practice

William & Mary Law Review Volume 50 (2008-2009) Issue 4 The Citizen Lawyer Symposium Article 5 3-1-2009 "Public Service Must Begin at Home": The Lawyer as Civics Teacher in Everyday Practice Bruce A. Green Russell G. Pearce Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Repository Citation Bruce A. Green and Russell G. Pearce, "Public Service Must Begin at Home": The Lawyer as Civics Teacher in Everyday Practice, 50 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 1207 (2009), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol50/iss4/5 Copyright c 2009 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr "PUBLIC SERVICE MUST BEGIN AT HOME": THE LAWYER AS CIVICS TEACHER IN EVERYDAY PRACTICE BRUCE A. GREEN* & RUSSELL G. PEARCE** TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................... 1208 I. THE IDEA OF THE LAWYER AS Civics TEACHER ........... 1213 II. WHY LAWYERS SHOULD TEACH CIVICS WELL ........... 1219 A. Teaching Civics Well as a Public Service ............ 1220 B. Teaching Civics Well as Intrinsic to the Lawyer's Social Function ......................... 1223 1. The ABA /AALS Report's Idea of Lawyers' PedagogicRole as Derived from Their Social Function .......................... 1223 2. Antecedents to the ABA /AALS Report's Idea of Lawyers'PedagogicRole ........................ 1227 3. The Perpetuationof the ABA/AALS Report's Idea of Lawyers'PedagogicRole ................. 1231 III. THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE CONCEPT IN PROFESSIONAL AND ACADEMIC DISCOURSE ............. 1233 A. Serving the Public Good ......................... 1233 B. The Lawyer's Role in a Democracy ................ -

Civics and Economics CE.6 Study Guide

HISTORY AND SOCIAL SCIENCE STANDARDS OF LEARNING • Prepares the annual budget for congressional action CURRICULUM FRAMEWORK 2008 (NEW) Reformatted version created by SOLpass • Appoints cabinet officers, ambassadors, and federal judges www.solpass.org Civics and Economics • Administers the federal bureaucracy The judicial branch CE.6 Study Guide • Consists of the federal courts, including the Supreme Court, the highest court in the land • The Supreme Court exercises the power of judicial review. • The federal courts try cases involving federal law and questions involving interpretation of the Constitution of the United States. STANDARD CE.6A -- NATIONAL GOVERNMENT STRUCTURE The structure and powers of the national government. The Constitution of the United States defines the structure and powers of the national government. The powers held by government are divided between the national government in Washington, D.C., and the governments of the 50 states. What is the structure of the national government as set out in the United States Constitution? STANDARD CE.6B What are the powers of the national government? -- SEPARATION OF POWERS Legislative, executive, and judicial powers of the national government are distributed among three distinct and independent branches of government. The principle of separation of powers and the operation of checks and balances. The legislative branch • Consists of the Congress, a bicameral legislature The powers of the national government are separated consisting of the House of Representatives (435 among three -

Final Report of the Committee to Study the Scope And

STATE OF MAINE 121ST LEGISLATURE FIRST REGULAR SESSION Final Report of the Commission to Study the Scope and Quality of Citizenship Education February 2004 Members: Senator Neria R. Douglas, Chair Representative Glenn Cummings, Chair Senator Betty Lou Mitchell Representative Gerald M. Davis Joseph Burnham Gale Caddoo Amanda Coffin Staff: Christopher J. Hall Phillip D. McCarthy, Ed.D., Legislative Analyst Judith Harvey Nicole A. Dube, Legislative Analyst Kurt Hoffman Richard Marchi Office of Policy & Legal Analysis Denise O’Toole Maine Legislature Elizabeth McCabe Park (207) 287-1670 Patrick Phillips http://www.state.me.us/legis/opla/ Francine Rudoff Table of Contents Page Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... i I. Introduction....................................................................................................... 1 II. Background ....................................................................................................... 4 III. Summary of Key Findings ................................................................................ 8 IV. Conclusions and Recommendations ............................................................... 15 Appendices A. Authorizing Legislation, Resolve 2003, Chapter 85 B. Membership List, Commission to Study the Scope and Quality of Citizenship Education C. Resource People and Presenters Providing Information to the Commission D. Definitions E. Bibliography of Citizenship Education Materials F. Citizenship -

Senate Confirms Acting OMB Chief to Be Permanent Director

https://www.govexec.com/management/2020/07/senate-confirms-acting-omb-chief-be- permanent-director/166623/ Management Senate Confirms Acting OMB Chief to Be Permanent Director Russell Vought has said he will "be as responsive as we possibly can" to Congress and prioritize requests from overseers related to the novel coronavirus pandemic. JULY 20, 2020 COURTNEY BUBLÉ Late Monday afternoon, the Senate voted 51-45, along party lines, to confirm acting Office of Management and Budget Director Russell Vought to fill the position permanently. Vought was the OMB deputy director from early in the Trump administration and then took over as acting OMB head in January 2019 when Mick Mulvaney left to become the president’s acting chief of staff. President Trump announced his intent to nominate Vought as the permanent OMB director on March 18. Vought has been able to remain as acting director due to two exceptions under the 1998 Federal Vacancies Reform Act, which typically precludes acting officials from remaining in their roles once they are formally nominated. As acting director, Vought has pushed for evidence-based policy making, championed the administration’s deregulatory agenda and handled the aftermath of the longest government shutdown in history. Also, during Vought’s tenure watchdogs and Democratic lawmakers have raised concerns about the Trump administration's perceived lack of cooperation with various investigative probes. During his confirmation hearing in June, Vought said he will “be as responsive as we possibly can” to Congress and “certainly work with [the Government Accountability Office] closely [since] it is our practice to do that.” He also said he would prioritize requests about the novel coronavirus pandemic. -

[email protected] Dionne Hardy FOIA Officer Office Of

February 12, 2020 BY EMAIL: [email protected] Dionne Hardy FOIA Officer Office of Management and Budget 725 17th Street, N.W., Suite 9204 Washington, D.C. 20503 Re: Freedom of Information Act Request Dear Ms. Hardy: Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (“CREW”) makes this request pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”), 5 U.S.C. § 552, and Office of Management and Budget (“OMB”) regulations. First, CREW requests records sufficient to show every delegation of authority by an OMB Director to any other officer or employee that was in effect at any time from December 1, 2018 to present. Second, CREW requests all email communications sent to or received by OMB Acting Director Russell Vought, OMB Deputy Director for Management Margaret Weichert, or OMB General Counsel Mark Paoletta from December 1, 2018 to the present regarding any delegation of authority to an OMB officer or employee by OMB Director John Michael “Mick” Mulvaney. This request includes, but is not limited to, records tied to any email address Mr. Vought, Ms. Weichert, or Mr. Paoletta has used to conduct OMB business, not just email addresses with the domain @omb.eop.gov. Third, CREW requests all records of reimbursement(s) made to OMB by the White House Office or any other component of the Executive Office of the President from December 1, 2018 to the present in connection with Mr. Mulvaney’s detail to serve as Acting White House Chief of Staff, including the reimbursement of salary or any other item or expense associated with the detail.