The Post-Truth Reception of Hamilton (2015) and the New Prince (2017)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mohammed Fairouz: an Appreciation by Rick Schultz

Artist Biographies & Liner Notes “Zabur” Indianapolis Symphonic Choir Mohammed Fairouz: An Appreciation by Rick Schultz Zabur is Mohammed Fairouz's first oratorio, a genre for large orchestra, choir and soloists going back centuries. Such rich musical soil allows Fairouz to create a sacred dialogue -- a dialogue not just between characters, but also between the artist and his listeners. From its powerful choral opening, Zabur doesn't let up, placing us directly into a theater of war where a city is under siege. Like one of his literary predecessors, English poet William Blake, Fairouz rages against those "who would if they could, for ever depress Mental & prolong Corporeal War." Fairouz, an Emirati-American composer, once characterized himself as a "creature of the desert," referring to his deep Middle Eastern roots. Dry desert winds often drift across his emotionally resonant musical landscapes. But Fairouz, one of our country's most essential storytellers, isn't out to lecture anyone. His mission, if he has one, is to beautify the world -- to create art as a counterforce to dehumanization, as a bridge to our universal past. One of Fairouz's most aching and ravishing scores, Zabur conjures a timeless world in song settings of epic grandeur and shattering intimacy. Like his Symphony No. 3 ("Poems and Prayers"), Zabur becomes an enticement to feel. By revealing our shared emotions and experiences, Fairouz allows us to recharge our humanity amid a surfeit of numbing images of disaster and atrocity. At the conclusion of "Poems and Prayers," Fairouz sets Yehuda Amichai's poem "Memorial Day for the War Dead," in which the poet hopes that behind so much sorrow, "some great happiness is hiding." Paradoxically, what makes Zabur such a compelling war requiem is its optimism. -

Chorale Fantasy.MUS

MOHAMMED FAIROUZ CHORALE FANTASY for String Quartet MOHAMMED FAIROUZ CHORALE FANTASY for String Quartet Chorale Fantasy was written in response to the Borromeo String Quartet’s initiative to com- mission a set of chorale preludes. This short work lives in the world between maqam (Arabic modes) and gentle counterpoint. It opens with a short introduction leading to a violin line with unheard lyrics against an insisting drone. It then conspires into a whirling dance reaching a vocal climax and returns at the end to the gentleness of the opening. All of the parts of Chorale Fantasy are written within the singing range of the human voice. The work is affectionately dedicated to the Borromeo Quartet. —Mohammed Fairouz Chorale Fantasy is recorded on "Native Informant," Naxos American Classics CD 8.559744, performed by the Borromeo String Quartet. Mohammed Fairouz, born in 1985, is one of the most frequently performed, commissioned, and recorded composers of his generation. Hailed by The New York Times as “an important new artistic voice” and by BBC World News as “one of the most talented composers of his generation,” Fairouz melds Middle-Eastern modes and Western structures to deeply expressive effect. His large-scale works, including four symphonies and an opera, engage major geopolitical and philosophical themes with persuasive craft and a marked seriousness of purpose. His solo and chamber music attains an “intoxicating intimacy,” according to New York’s WQXR. A truly cosmopolitan voice, Fairouz had a transatlantic upbringing. By his early teens, the Arab- American composer had traveled across five continents, immersing himself in the musical life of his surroundings. -

Oliver Knussen Ensemble Signal Brad Lubman, Conductor

Miller Theatre at Columbia University 2012-13 | 24th Season Composer Portraits Oliver Knussen Ensemble Signal Brad Lubman, conductor Thursday, April 18, 8:00 p.m. Miller Theatre at Columbia University 2012-13 | 24th Season Composer Portraits Oliver Knussen Ensemble Signal Brad Lubman, conductor Rachel Calloway, mezzo-soprano Jamie Jordan, soprano Courtney Orlando, violin Thursday, April 18, 8:00 p.m. Ophelia Dances, Book 1 (1975) Oliver Knussen (b. 1952) Brad Lubman, conductor Secret Psalm (1990) Courtney Orlando, violin Hums and Songs of Winnie-the-Pooh (1970/1983) I. Aphorisms: 1. Inscription 2. Hum 3. The Hundred Acre Wood (Nocturne) 3a. Piglet Meets a Heffalump 4. Hum, continued, and Little Nonsense Song 5. Hum 6. Vocalise (Climbing the Tree) 7. Codetta II. Bee Piece III. Cloud Piece Jamie Jordan, soprano Brad Lubman, conductor INTERMISSION Miller Theatre at Columbia University 2012-13 | 24th Season Onstage discussion with Oliver Knussen and Brad Lubman Songs without Voices (1991-92) I. Fantastico (Winter’s Foil) II. Maestoso (Prairie Sunset) III. Leggiero (First Dandelion) IV. Adagio (Elegiac Arabesques) Brad Lubman, conductor Requiem – Songs for Sue (2005-06) Rachel Calloway, mezzo-soprano Brad Lubman, conductor This program runs approximately one hour and 20 minutes, including a brief intermission. Major support for Composer Portraits is provided by the Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts. Composer Portraits is presented with the friendly support of Please note that photography and the use of recording devices are not permitted. Remember to turn off all cellular phones and pagers before tonight’s performance begins. Miller Theatre is wheelchair accessible. Large print programs are available upon request. -

New on Naxos | November 2013

NEWThe World’s O LeadingN ClassicalNAX MusicOS Label NOVEMBER 2013 This Month’s Other Highlights © 2013 Naxos Rights US, Inc. • Contact Us: [email protected] www.naxos.com • www.classicsonline.com • www.naxosmusiclibrary.com • blog.naxos.com NEW ON NAXOS | NOVEMBER 2013 Leonard Slatkin Maurice RAVEL (1875–1937) Orchestral Works, Volume 2 Orchestre National de Lyon • Leonard Slatkin Valses nobles et sentimentales Gaspard de la nuit (orch. Marius Constant) Le tombeau de Couperin • La valse Maurice Ravel’s Valses nobles et sentimentales present a vivid mixture of atmospheric impressionism, intense expression and modernist wit, his fascination with the waltz further explored in La valse, a mysterious evocation of a vanished imperial epoch. Heard here in an orchestration by Marius Constant, Gaspard de la nuit is Ravel’s response to the other-worldly poems of Aloysius Bertrand, and the dance suite Le tombeau de Couperin is a tribute to friends who fell in the war of 1914-18 as well as a great 18th century musical forbear. ‘It is a delightful and assorted collection… presented in splendid performances by the Orchestre National de Lyon led by their music director, the venerable American conductor Leonard Slatkin.’ (Classical.net / Volume 1, 8.572887) Volume 1 of this series of Ravel’s orchestral music (8.572887 and NBD0030) has proved an immediate hit and has been warmly received by the press. Gramophone admired Leonard Slatkin’s ‘affinity with [Ravel’s] particular world of sound’, and of the Orchestre National de Lyon, stated that ‘it augurs well as a companion to the orchestra’s Debussy set 8.572888 Playing Time: 66:39 under Jun Märkl.’ The Blu-ray version provides a spectacular alternative to CD, ‘the orchestral colors… are beautifully realized by Slatkin and his forces, and well-preserved in either hi-res format’ (Audiophile Audition 7 47313 28887 8 5-star review). -

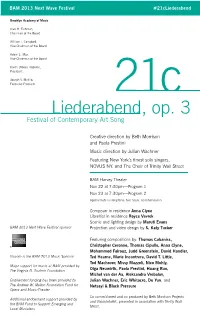

21C Liederabend , Op 3

BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival #21cLiederabend Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer 21c Liederabend, op. 3 Festival of Contemporary Art Song Creative direction by Beth Morrison and Paola Prestini Music direction by Julian Wachner Featuring New York’s finest solo singers, NOVUS NY, and The Choir of Trinity Wall Street BAM Harvey Theater Nov 22 at 7:30pm—Program 1 Nov 23 at 7:30pm—Program 2 Approximate running time: two hours, no intermission Composer in residence Anna Clyne Librettist in residence Royce Vavrek Scenic and lighting design by Maruti Evans BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival sponsor Projection and video design by S. Katy Tucker Featuring compositions by: Thomas Cabaniss, Christopher Ceronne, Thomas Cipullo, Anna Clyne, Mohammed Fairouz, Judd Greenstein, David Handler, Viacom is the BAM 2013 Music Sponsor Ted Hearne, Marie Incontrera, David T. Little, Tod Machover, Missy Mazzoli, Nico Muhly, Major support for music at BAM provided by The Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation Olga Neuwirth, Paola Prestini, Huang Ruo, Michel van der Aa, Aleksandra Vrebalov, Endowment funding has been provided by Julian Wachner, Eric Whitacre, Du Yun, and The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fund for Netsayi & Black Pressure Opera and Music-Theater Co-commisioned and co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects Additional endowment support provided by and VisionIntoArt, presented in association with Trinity Wall the BAM Fund to Support Emerging and Street. Local Musicians 21c Liederabend Op. 3 Being educated in a classical conservatory, the Liederabend (literally “Song Night” and pronounced “leader-ah-bent”) was a major part of our vocal educations. -

Study Guide for Sumeida's Song, Version 2.Pub

Pittsburgh Opera The Inspiration for Sumeida’s Song by Jill Leahy Education thanks our Tawf īq al-Ḥak īm, (b. Oct. 9, 1898, Alexandria, Egypt – d. July 26, 1987, Cairo), generous supporters: is considered to be the founder of contemporary Egyptian drama and a leading figure in modern Arabic literature. His American Eagle Outfitters, Inc. wealthy family wanted him to become a lawyer, but after Bayer USA Foundation Sumeida’s Song traveling to Paris to continue his legal studies, he fell in love The Frick Fund of the Buhl nson-Davies, with Western theater. On his return to Egypt, he worked in Foundation several government positions, but he eventually resigned The Jack Buncher Foundation and spent all his time writing, eventually writing more than Dominion Foundation 50 plays. Eat ‘n Park Hospitality Group, Inc. He became famous ESB Bank as a dramatist with First Commonwealth Ahl al-kahf (1933; The Financial Corporation al-Hakim Ismail Tawfiq by People of the Cave ), The Grable Foundation which on the surface The Hearst Foundation Rachel Calloway andDan Kempson thein 2009 World Premiere Production of Jill Steinberg) (Photo by http://mohammedfairouz.com/sumeidas-song-2009/ appeared to be based Hefren-Tillotson, Inc. on the ancient legend Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield Opera Vancouver at Tim Matheson by Photo Production The High Cost of Family Honor by Jill Leahy of the Seven Sleepers The Huntington National Bank Sumeida’s Song , a chamber opera in three scenes, was written in 2009 and of Ephesus, but “was Intermediate Unit #1, Pennsylvania had its first fully-staged production as the opening event of the first actually a study of the Department of Education "Prototype: Opera/Theater/Now" festival in New York in January 2013. -

Calendar of Events

Contact: Jessica Wolf, Communications Manager [email protected] 310.825.7789 Image Library: cap.ucla.edu/press CENTER FOR THE ART OF PERFORMANCE AT UCLA 2013-2014 SEASON 2012-2013 Venues Royce Hall 340 Royce Drive Parking: Lot 5 Schoenberg Hall 445 Charles E. Young Dr., East Parking: Lot 2 Freud Playhouse at Macgowan Hall 245 Charles E. Young Dr., East Parking: Lot 3 Little Theater at Macgowan Hall 245 Charles E. Young Dr., East Parking: Lot 3 Fowler Museum at UCLA 308 Charles E. Young Dr., North The Actor’s Gang at The Ivy Substation 9070 Venice Blvd. Culver City 90232 Parking: Street/Lot Ticket information : UCLA Central Ticket Office 310.825.2101 Subscription packages on sale April 23. Individual tickets on sale July 11. Ticket prices listed are advertised price. Season subscriptions in Theater, Dance, Spoken Word, Jazz, Roots/Folk, Global Music, Contemporary Music, Tune-In Festival L.A., Family and Royce Choice include a 15 percent discount off advertised price. Create-Your-Own subscriptions of five or more performances include a 10 percent discount. *Indicates no-discount shows. **Indicates UCLA student ticket price. All prices and programs are subject to change. Calendar of Events SEPTEMBER The Moth: Saints and Sinners Spoken Word/ Royce Hall Tues., Sept. 10 – 8 p.m. $50/40/$35/$40/$25/$15** Outlaws and angels, on the cusp of darkness or drawn to the light. Join us for true stories of haloes and horns, good and evil, the naughty and the nice and those who dabble on both sides of the spectrum. -

Opera Project That Received NEA Funding

Nov 2018 Under the Freedom of Information Act, agencies are required to proactively disclose frequently requested records. Often the National Endowment for the Arts receives requests for examples of funded grant proposals for various disciplines. In response, the NEA is providing examples of the “Project Information” also called the ”narrative” for a successful Opera project that received NEA funding. The selected examples is not the entire funded grant proposal and only contain the grant narrative and selected portions. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. The following narratives have been selected as example because it represents a diversity of project type and is well written. Although the project was funded by the NEA, please note that nothing should be inferred about the ranking of each application within its respective applicant pool. We hope that you will find these records useful as an example of a well written narrative. However please keep in mind that because each project is unique, these narrative should be used as reference, rather than templates. If you are preparing your own application and have any questions, please contact the appropriate program office. You may also find additional information regarding the grant application process on our website at Apply for a Grant | NEA . Opera Opera for the Young (Opera for the Young) Beth Morrison Project (Commissioning) Utah Symphony & Opera (Repeat Productions of Newly Premiered Works) Glimmerglass Opera (Opera Festival) Patrick G. and Shirley Ryan Opera Center (Young Artist Program) Opera Omaha (World Premiere) 16-973749 Attachments-ATT20-Project_Information.pdf Opera for the Young, Inc. -

The Eighth Season Maps and Legends CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 23–August 14, 2010 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Eighth Season Maps and Legends CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 23–August 14, 2010 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE 50 Valparaiso Avenue • Atherton, California 94027 • 650-330-2030 www.musicatmenlo.org Date Free Events Ticketed Events Tuesday, 11:45 a.m. Master class: Ralph Kirshbaum, cellist PAGE 67 8:00 p.m. Carte Blanche Concert III: The Beethoven Sonatas PAGE 48 August 3 Martin Family Hall for Piano and Cello David Finckel, cello; Wu Han, piano The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton Wednesday, 11:45 a.m. Café Conversation: Poetry Reading Workshop PAGE 66 8:00 p.m. Concert Program IV: Aftermath: 1945 PAGE 23 August 4 with Violinist Jorja Fleezanis and Stent Family Hall Artistic Administrator Patrick Castillo Martin Family Hall 6:00 p.m. Prelude Performance PAGE 59 Martin Family Hall Thursday, 11:45 a.m. Master class: Miró Quartet PAGE 67 8:00 p.m. Concert Program IV: Aftermath: 1945 PAGE 23 August 5 Martin Family Hall The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton 6:00 p.m. Koret Young Performers Concert PAGE 64 The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton Friday, 11:45 a.m. Master class: Bruce Adolphe, composer PAGE 67 7:30 p.m. Encounter III: Under the Influence: PAGE 10 August 6 and Encounter leader Cultural Collage in Paris during the Martin Family Hall Early Twentieth Century, with Bruce Adolphe 5:30 p.m. Prelude Performance PAGE 59 Martin Family Hall Stent Family Hall Saturday, 2:00 p.m. Koret Young Performers Concert PAGE 64 8:00 p.m. -

Pasadena Symphony 2016-‐17 Classics Season Artist Bios ABOUT

Pasadena Symphony 2016-17 Classics Season Artist Bios ABOUT THE ARTISTS David Lockington Music Director Over the past thirty-five years, David Lockington has developed an impressive conducting career in the United States. A native of Great Britain, he served as the Music Director of the Grand Rapids Symphony from January 1999 to May 2015, and is currently the orchestra’s Conductor Laureate. He has held the position of Music Director with the Modesto Symphony since May 2007 and in March 2013, Mr. Lockington was appointed to the same position with the Pasadena Symphony. He also has a close relationship with the Orquesta Sinfonica del Principado de Asturias in Spain where he is currently the orchestra’s Principal Guest Conductor, and beginning with the 15/16 season he will be one of three Artistic Partners with the Northwest Sinfonietta in Tacoma, Washington. In addition to his current posts, since his arrival to the United States in 1978 Mr. Lockington has also held additional positions with American orchestras, including serving as Assistant Conductor of the Denver Symphony Orchestra and Opera Colorado and Assistant and Associate Conductor of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra. In May 1993 he accepted the position of Music Director of the Ohio Chamber Orchestra, assumed the title of Music Director of the New Mexico Symphony Orchestra in September 1995 and was Music Director of the Long Island Philharmonic for the 96/97 through 99/2000 seasons. Mr. Lockington's guest conducting engagements include appearances with the Saint Louis, Houston, Detroit, Seattle, Toronto, Vancouver, Oregon and Phoenix symphonies; the Rochester and Louisiana Philharmonics; and the Orchestra of St. -

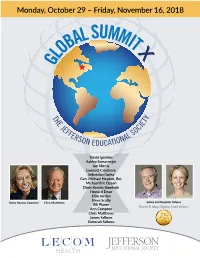

Globalsummit X

Event Sponsors Monday, October 29 – Friday, November 16, 2018 Thank You LSUMM Platinum BA IT LO X G Gold Silver Bronze Copper T H Y E T IE JE C GOHRS F O p: (814) 455-0629 · f: (814) 454-2718 FE S RS AL Patron Sponsors ON EDUCATION David Ignatius Personal Patrons Ashley Swearengin Ian Morris Maureen Plunkett and Family Anonymous Jefferson Trustee Leonard Calabrese Sebastian Gorka Gen. Michael Hayden, Ret. Michael Eric Dyson Thomas Jefferson believed a citizenry that was educated on issues and shared its ideas through public discourse had the power to make a difference in the world. Doris Kearns Goodwin Howard Dean The Jefferson Educational Society of Erie is a strong proponent of that belief, offering courses, seminars,and lectures that explain the ideas that formed the past, assist in exploring the present,and offer guidance in creating the future of the Erie region. Elise Jordan Steve Scully Doris Kearns Goodwin Chris Matthews James and Deborah Fallows Bill Plante Thomas B. Hagen Dignitas Award Winners 3207 State Street Ann Compton Erie, Pennsylvania Chris Matthews 16508-2821 James Fallows XXDeborah Fallows Dear Friends: Welcome to the Jefferson Educational Society’s Global Summit X! This important lecture series could not come at a more opportune time, as we address some of the key issues facing the Erie community, our country, and the world. As this event enters its 10th year, we can reflect proudly on last year’s summit, which marked the first time the Global Summit stretched into a third week! We heard nine great presentations from 13 of the most respected scholars, writers, and leaders in their respective fields. -

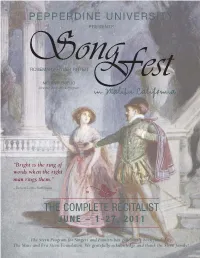

Jake Heggie – Songfest 2011 Distinguished Faculty Jake Heggie – Composer-In-Residence

PEPPERDINE UNIVERSITY PRESENTS ROSEMARY HYLER RITTER Director MELANIE EMELIO Director, Apprentice Program in Malibu California “Bright is the ring of words when the right man rings them.” – Robert Lewis Stevenson THE COMPLETE RECITALIST JUNE – 1-27, 2011 The Stern Program for Singers and Pianists has generously been funded by The Marc and Eva Stern Foundation. We gratefully acknowledge and thank the Stern family! Welcome to SongFest 2011 “Whatever you can do, or dream you can do, you can. Boldness has a genius, magic and power to it.” – Goethe SongFest 2011 is supported by grants from The Marc and Eva Stern Foundation, The Aaron Copland Fund for Music, The Louise K. Smith Family Foundation and the generosity of many individuals. Photos by Ron Hall Photography ©2010 SongFest is a 501(c)3 non profit corporation. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent permitted by law. JAKE HEGGIE – SONGFEST 2011 DISTINGUISHED FACULTY JAKE HEGGIE – COMPOSER-IN-RESIDENCE SongFest 2011 • Pepperdine University • Biography Jake Heggie Composer, Pianist JAKE HEGGIE is the Jake Heggie’s operas have been performed to American composer of tremendous acclaim internationally in Australia, the operas Moby-Dick Canada, Denmark, Germany, Sweden, Ireland, Austria, (libretto: Gene Scheer), South Africa and by more than a dozen American opera Dead Man Walking companies. The composer’s numerous songs and cycles, (libretto: Terrence including The Deepest Desire, Statuesque, Here & Gone, McNally), Three Rise & Fall, Songs & Sonnets to Ophelia, Facing Decembers