Labor Research: 1) Read “A Miner's Story” and Explain As Many of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Fear Is Substituted for Reason: European and Western Government Policies Regarding National Security 1789-1919

WHEN FEAR IS SUBSTITUTED FOR REASON: EUROPEAN AND WESTERN GOVERNMENT POLICIES REGARDING NATIONAL SECURITY 1789-1919 Norma Lisa Flores A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2012 Committee: Dr. Beth Griech-Polelle, Advisor Dr. Mark Simon Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Michael Brooks Dr. Geoff Howes Dr. Michael Jakobson © 2012 Norma Lisa Flores All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Beth Griech-Polelle, Advisor Although the twentieth century is perceived as the era of international wars and revolutions, the basis of these proceedings are actually rooted in the events of the nineteenth century. When anything that challenged the authority of the state – concepts based on enlightenment, immigration, or socialism – were deemed to be a threat to the status quo and immediately eliminated by way of legal restrictions. Once the façade of the Old World was completely severed following the Great War, nations in Europe and throughout the West started to revive various nineteenth century laws in an attempt to suppress the outbreak of radicalism that preceded the 1919 revolutions. What this dissertation offers is an extended understanding of how nineteenth century government policies toward radicalism fostered an environment of increased national security during Germany’s 1919 Spartacist Uprising and the 1919/1920 Palmer Raids in the United States. Using the French Revolution as a starting point, this study allows the reader the opportunity to put events like the 1848 revolutions, the rise of the First and Second Internationals, political fallouts, nineteenth century imperialism, nativism, Social Darwinism, and movements for self-government into a broader historical context. -

Haymarket Riot (Chicago: Alexander J

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 HAYMARKET MARTYRS1 MONUMENT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service______________________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Haymarket Martyrs' Monument Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 863 South Des Plaines Avenue Not for publication: City/Town: Forest Park Vicinity: State: IL County: Cook Code: 031 Zip Code: 60130 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): Public-Local: _ District: Public-State: _ Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing ___ buildings ___ sites ___ structures 1 ___ objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register:_Q_ Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: Designated a NATIONAL HISTrjPT LANDMARK on by the Secreury 01 j^ tai-M NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 HAYMARKET MARTYRS' MONUMENT Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National_P_ark Service___________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Adaptation As Anarchist

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2012 Adaptation as Anarchist: A Complexity Method for Ideology-Critique of American Crime Narratives Kristopher Mecholsky Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Mecholsky, Kristopher, "Adaptation as Anarchist: A Complexity Method for Ideology-Critique of American Crime Narratives" (2012). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3247. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3247 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. ADAPTATION AS ANARCHIST: A COMPLEXITY METHOD FOR IDEOLOGY-CRITIQUE OF AMERICAN CRIME NARRATIVES A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Kristopher Mecholsky B.A., The Catholic University of America, 2004 M.A., Marymount University, 2008 August 2012 Copyright © 2012 by Kristopher Mecholsky All rights reserved ii Perhaps the sentiments contained in the following pages, are not yet sufficiently fashionable to procure them general favour… Thomas Paine, Common Sense iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This section was originally a lot longer, a lot funnier, and a lot more grateful. Before I thank anyone, let me apologize to those I cannot list here. Know that deep in my computer, a file remains saved, inscribed with eloquent gratitude. -

Colouring-Book-Vol-2-Final-GHC.Pdf

Colouring outside the Lines Colouring is cool again! These days, many stores carry a vast array of colouring and activity books on a variety of topics, from popular TV shows to cute cats and exotic plants. There is even an adult colouring book “For Dummies,” promising to guide people through the basics of colouring in case they need a refresher. Most of these books market colouring as a fun, creative, and mindless distraction, and there is something soothing about getting lost in adding colour to an intricate illustration. Colouring can help us relax and reduce stress and can also serve as a form of meditation. Moreover, colouring taps into our nostalgia for childhood, a time when life was simpler and we had less responsibility. In short, most adult colouring books sell us on the fact that life is busy and difficult, but colouring is simple and fun! The Little Red Colouring Book has a different objective. Our art aims to fan the flames of discontent rather than snuff them out. Taking inspiration from the Industrial Workers of the World’s Little Red Song Book, The Little Red Colouring Book offers a mindful activity to inspire people to learn more about historical labour activists and revolutionaries that fought for the rights and freedoms many of us take for granted today. Volume 2 focuses on the Haymarket Martyrs. Many people are not aware that May Day, International Workers’ Day, or May 1, commemorates the 1886 Haymarket affair. The event involved eight anarchists in Chicago who were wrongly convicted of throwing a bomb at police during a labour demonstration in support of workers striking for the eight-hour day. -

Praise for Revolution and Other Writings: a Political Reader

PRAISE FOR REVOLUTION AND OTHER WRITINGS: A POLITICAL READER If there were any justice in this world – at least as far as historical memory goes – then Gustav Landauer would be remembered, right along with Bakunin and Kropotkin, as one of anarchism's most brilliant and original theorists. Instead, history has abetted the crime of his murderers, burying his work in silence. With this anthology, Gabriel Kuhn has single-handed- ly redressed one of the cruelest gaps in Anglo-American anarchist litera- ture: the absence of almost any English translations of Landauer. – Jesse Cohn, author of Anarchism and the Crisis of Representation: Hermeneutics, Aesthetics, Politics Gustav Landauer was, without doubt, one of the brightest intellectual lights within the revolutionary circles of fin de siècle Europe. In this remarkable anthology, Gabriel Kuhn brings together an extensive and splendidly chosen collection of Landauer's most important writings, presenting them for the first time in English translation. With Landauer's ideas coming of age today perhaps more than ever before, Kuhn's work is a valuable and timely piece of scholarship, and one which should be required reading for anyone with an interest in radical social change. – James Horrox, author of A Living Revolution: Anarchism in the Kibbutz Movement Kuhn's meticulously edited book revives not only the "spirit of freedom," as Gustav Landauer put it, necessary for a new society but also the spirited voice of a German Jewish anarchist too long quieted by the lack of Eng- lish-language translations. Ahead of his time in many ways, Landauer now speaks volumes in this collection of his political writings to the zeitgeist of our own day: revolution from below. -

Civil Disobedience in Chicago: Revisiting the Haymarket Riot Samantha Wilson College of Dupage

ESSAI Volume 14 Article 40 Spring 2016 Civil Disobedience in Chicago: Revisiting the Haymarket Riot Samantha Wilson College of DuPage Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai Recommended Citation Wilson, Samantha (2016) "Civil Disobedience in Chicago: Revisiting the Haymarket Riot," ESSAI: Vol. 14 , Article 40. Available at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai/vol14/iss1/40 This Selection is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at DigitalCommons@COD. It has been accepted for inclusion in ESSAI by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@COD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wilson: Civil Disobedience in Chicago Civil Disobedience in Chicago: Revisiting the Haymarket Riot by Samantha Wilson (English 1102) he city of Chicago, Illinois, is no stranger to political uprisings, riots, protests, and violence. However, there has never been a movement that the police and Chicago elite desired to squash Tquickly quite like the anarchist uprising during the 1880s. In the period of time after the Chicago Fire, the population of the city tripled, exceeding one million people (Smith 101). While business was booming for men like George Pullman, the railcar tycoon, and Louis Sullivan, the architect, the Fire left over 100,000 people homeless, mostly German and Scandinavian immigrant laborers who were also subjected to low wages and poor working conditions. In winter of 1872, the Bread Riot began due to thousands marching on the Chicago Relief and Aid Society for access to money donated by people of the United States and other countries after the Fire. Instead of being acknowledged, police filed them into a tunnel under the Chicago River and beat them with clubs (Adelman 4-5). -

Labor's Martyrs: Haymarket 1887, Sacco and Vanzetti 1927

University of Central Florida STARS PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements 1-1-1937 Labor's martyrs: Haymarket 1887, Sacco and Vanzetti 1927 Vito Marcantonio Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/prism University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Book is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Marcantonio, Vito, "Labor's martyrs: Haymarket 1887, Sacco and Vanzetti 1927" (1937). PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements. 8. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/prism/8 PUBLISHED BY WORKERS LIBRARY PUBLISHERS, INC. P. O. BOX 148, STATION D, NEW YORK OCTOBF.R, ) 937 PaINTm IN U.S.A. INTRODUCTION BY WILLIAM Z. FOSTER N November 11, 1937, it is just fifty years since Albert R. O Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fischer, George Engel and Louis Lingg, leaders of the great eight-hour day national strike of 1886, were executed in Chicago on the framed-up charge of having organized the Haymarket bomb explosion that caused the death of a number of policemen. These early martyrs to labor's cause were legally lynched because of their loyal and intelligent strug gle for and with the working class. Their murder was encom passed by the same capitalist forces which, in our day, we have seen sacrifice Tom Mooney, Sacco and Vanzetti, the Scottsboro boys, McNamara, and a host of other champions of the oppressed. Parsons and his comrades were revolutionary trade unionists, they were Anarcho-Syndicalists rather than Anarchists. -

288381679.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository This item was submitted to Loughborough University as a PhD thesis by the author and is made available in the Institutional Repository (https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/) under the following Creative Commons Licence conditions. For the full text of this licence, please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ Towards a Libertarian Communism: A Conceptual History of the Intersections between Anarchisms and Marxisms By Saku Pinta Loughborough University Submitted to the Department of Politics, History and International Relations in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Approximate word count: 102 000 1. CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINALITY This is to certify that I am responsible for the work submitted in this thesis, that the original work is my own except as specified in acknowledgments or in footnotes, and that neither the thesis nor the original work contained therein has been submitted to this or any other institution for a degree. ……………………………………………. ( Signed ) ……………………………………………. ( Date) 2 2. Thesis Access Form Copy No …………...……………………. Location ………………………………………………….……………...… Author …………...………………………………………………………………………………………………..……. Title …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Status of access OPEN / RESTRICTED / CONFIDENTIAL Moratorium Period :…………………………………years, ending…………../…………20………………………. Conditions of access approved by (CAPITALS):…………………………………………………………………… Supervisor (Signature)………………………………………………...…………………………………... Department of ……………………………………………………………………...………………………………… Author's Declaration : I agree the following conditions: Open access work shall be made available (in the University and externally) and reproduced as necessary at the discretion of the University Librarian or Head of Department. It may also be digitised by the British Library and made freely available on the Internet to registered users of the EThOS service subject to the EThOS supply agreements. -

Lesson Title: Haymarket Conclusion – Direct Lesson and Inquiry Lesson

Lesson Title: Haymarket Conclusion – Direct Lesson and Inquiry Lesson Standards: NCSS Themes: I. Culture II. Time, Continuity, and Change V. Individuals, Groups, and Institutions VI. Power, Authority, and Governance VII. Civic Ideals and Practices Illinois Learning Standards: Goal 16: Understand events, trends, individuals, and movements shaping the history of Illinois, the United States, and other nations. A. Apply the skills of historical analysis and interpretation. 16. A.4b Compare competing historical interpretations of an event. 16.A.5a Analyze historical and contemporary developments using methods of historical inquiry (pose questions, collect and analyze data, make and support inferences with evidence, report findings). B. Understand the development of significant political events. 16.B.4b (W) Identify political ideas from the early modern historical era to the present which have had worldwide impact. C. Understand the development of economic systems. 16.C.5b (US) Analyze the relationship between an issue in United States economic history and the related aspects of political, social and environmental history. Objectives: By the end of this lesson, students will: 1. Understand the effects of the Haymarket Affair on the labor movement. 2. Know how to use the historical inquiry process. Materials/Equipment: ο Chalk/marker board ο Chalk/marker ο PowerPoint or transparencies including: . images of Lingg’s suicide, http://www.chicagohistory.org/dramas/act4/shadowOfTheGallows/shadowOfTheGallows_f.htm . illustration, “The Chicago Anarchists Pay the Penalty of their Crime,” http://www.chicagohistory.org/dramas/act4/powerfulSilence/powerfulSilence_f.htm ο Historical inquiry format (for Haymarket conclusion) ο Paper, colored pencils for posters and political cartoons ο Gompers, Samuel (head of AFL). -

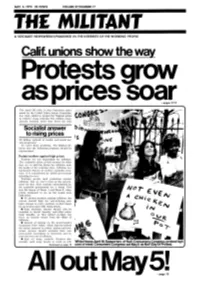

Calif. Unions Show the Way

MAY 4, 1973 25 CENTS VOLUME 37/NUMBER 17 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE Calif. unions show the way_ • -pages 9-12 The April 28 rally in San Francisco, spon sored by the United Labor Action Committee, has been called to protest the "highest prices in history; wage controls; five million unem ployed; unequal taxes that favor the rich; Socialist answer to rising prices $8 billion cutback in health and social ser vice programs." To solve these problems, The Militant be lieves that the following program should be implemented: Protect workers against high prices Workers are not responsible for inflation. The capitalist rulers of this country lie when they try to shift the blame for inflation onto the backs of the working class. Inflation is a permanent feature of modern capitalist econ omy. It is exacerbated by deficit government spending for war. Working people need protection against inflation. But we can't count on the govern ment for this. Price controls administered by the capitalist government are a fraud. This was the lesson of Phase 1 and Phase 2, when prices continued to go up but wages were held down. e To protect workers against inflation, the unions should fight for cost-of-living esca lator clauses in every contract, so that wages go up to keep pace with rising prices. e Such escalator clauses should also be included in Social Security and other retire ment benefits, so that retired workers can have an income secure from the effects of inflation. e Instead of relying on the government's Consumer Price Index, which lags far behind the actual increase in prices, unions and con sumer groups should organize their own price-watch committees to document and ex pose the real rate of inflation. -

Haymarket Chronology

Haymarket Chronology June 2010 for the Regina Polk Conference General strike for 8-hour work day In the winter and spring of 1886, the enthusiasm for the 8-hour work day had infected the skilled and unskilled laborers in Chicago. The national strike was to begin on May 1. The strike was held on the anniversary of when the nation’s first 8-hour work day law became effective upon then Illinois Governor Richard J. Oglesby’s signature on May 2nd, 1867. But the governor did not have the strength to stand up to business, so the law was never enforced. Chronology May 1, 1886 -- Coordinated strikes and demonstrations are held nationwide, to demand an eight-hour workday for indus- trial workers. May 3, 1886 -- McCormick Reaper Works factory strike; un- armed strikers, police clash; several strikers are killed. (plant on right) August Spies, a leader of the anarchists was so disgusted with the shooting of the strikers that he called a mass meet- ing for the next day. Evening of May 4, 1886 -- A meeting of workingmen is held near Haymarket Square; police arrive to disperse the peaceful assembly; a bomb is thrown into the ranks of the police; the police open fire; workingmen evi- dently return fire; police and an unknown number of workingmen killed; the bomb thrower is unidentified. May 5- 6, 1886 -- Widespread public outrage and shock in Chicago and nationwide; police arrest anarchist and labor activists, including seven of the eight eventual defendants (Al- bert Parsons fled the city only to surrender himself on June 21.[on right). -

Download Illustrated PDF of This Pamphlet

MAY DAY Made in the USA Exported to the World “This is the first and only International Labor Day. It belongs to the working class and is dedicated to the Revolution.” —Eugene Debs, 1907 A Speak Out Now pamphlet May Day – Made in the USA, Exported to the World May Day (International Workers Day) is one of the most important working-class holidays. It originated in the United States in the 1880s with the struggle for the eight-hour day. The expansion of capitalism in 19th century America brought new layers of the working class into existence. Many were imbued with a strong class hatred for their oppressors. The workers’ movement spread from large urban centers to small towns, building new organizations and engaging in militant struggles. The major labor organization at the time was the Knights of Labor. It was born as a secret society in 1869 and by May 1886 it had a membership of over one million. The Knights combined the idea of the need for a class approach to organizing with a moral exhortation for good works and education. Their view was an “injury to one is the concern of all.” They also believed that wage slavery needed to be done away with and replaced by cooperatives of some kind. This made them quite different from the American Federation of Labor (founded in 1884 as the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions). The new AFL was based on the skilled labor of white, American-born males and was quite narrow in both its approach and its tactics of winning a better life.