The Beijing Trials: Secret Judicial Procedures and the Exclusion of Foreign Observers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

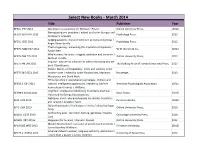

Select New Books - March 2014 Title Publisher Year BF321 .P67 2012 Attention in a Social World / Michael I

Select New Books - March 2014 Title Publisher Year BF321 .P67 2012 Attention in a social world / Michael I. Posner. Oxford University Press, c2012. Stereotyping and prejudice / edited by Charles Stangor and BF323.S63 S747 2013 Psychology Press, 2013. Christian S. Crandall. Judging passions : moral emotions in persons and groups / BF531 .G56 2012 Psychology Press, 2012. Roger Giner-Sorolla. That's disgusting : unraveling the mysteries of repulsion / BF575.A886 H47 2012 W.W. Norton & Co., c2012. Rachel Herz. Why humans like to cry : tragedy, evolution and the brain / BF575.C88 T75 2012 Oxford University Press, 2012. Michael Trimble. Impulse : why we do what we do without knowing why we BF575.I46 L49 2013 The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013. do it / David Lewis. Shame, blame, and culpability : crime and violence in the BF575.S45 S522 2013 modern state / edited by Judith Rowbotham, Marianna Routledge, 2013. Muravyeva, and David Nash. Ethical practice in operational psychology : military and BF636.3 .E84 2011 national intelligence applications / edited by Carrie H. American Psychological Association, c2011. Kennedy and Thomas J. Williams. Ungifted : intelligence redefined / Scott Barry Kaufman ; BF698.9.I6 K38 2013 Basic Books, [2013] illustrated by George Doutsiopoulos. Righteous mind : why good people are divided by politics BJ45 .H25 2012 Pantheon Books, c2012. and religion / Jonathan Haidt. Oxford handbook of the history of ethics / edited by Roger BJ71 .O94 2013 Oxford University Press, 2013. Crisp. Confronting evils : terrorism, torture, genocide / Claudia BJ1401 .C293 2010 Cambridge University Press, 2010. Card. BJ1481 .R87 2012x Happiness for humans / Daniel C. Russell. Oxford University Press, 2012. Muslim Brotherhood : evolution of an Islamist movement / BP10.I385 W53 2013 Princeton University, [2013] Carrie Rosefsky Wickham. -

Confession, Redemption, and Death: Liu Xiaobo and the Protest Movement of 1989

Confession, Redemption, and Death: Liu Xiaobo and the Protest Movement of 1989 Geremie Barmé1 There should be room for my extremism; I certainly don’t demand of others that they be like me... I’m pessimistic about mankind in general, but my pessimism does not allow for escape. Even though I might be faced with nothing but a series of tragedies, I will still struggle, still show my opposition. This is why I like Nietzsche and dislike Schopenhauer. Liu Xiaobo, November 19882 I FROM 1988 to early 1989, it was a common sentiment in Beijing that China was in crisis. Economic reform was faltering due to the lack of a coherent program of change or a unified approach to reforms among Chinese leaders and ambitious plans to free prices resulted in widespread panic over inflation; the question of political succession to Deng Xiaoping had taken alarming precedence once more as it became clear that Zhao Ziyang was under attack; nepotism was rife within the Party and corporate economy; egregious corruption and inflation added to dissatisfaction with educational policies and the feeling of hopelessness among intellectuals and university students who had profited little from the reforms; and the general state of cultural malaise and social ills combined to create a sense of impending doom. On top of this, the government seemed unwilling or incapable of attempting to find any new solutions to these problems. It enlisted once more the aid of propaganda, empty slogans, and rhetoric to stave off the mounting crisis. University students in Beijing appeared to be particularly heavy casualties of the general malaise. -

Standoff at Tiananmen: Recollections of 1989: the Making of Goddess of Democracy

2019/4/23 Standoff At Tiananmen: Recollections of 1989: The Making of Goddess of Democracy 更多 创建博客 登录 Standoff At Tiananmen How Chinese Students Shocked the World with a Magnificent Movement for Democracy and Liberty that Ended in the Tragic Tiananmen Massacre in 1989. Relive the history with this blog and my book, "Standoff at Tiananmen", a narrative history of the movement. Home Days People Documents Pictures Books Recollections Memorials Monday, May 30, 2011 "Standoff at Tiananmen" English Language Edition Recollections of 1989: The Making of Goddess of Democracy Click on the image to buy at Amazon "Standoff at Tiananmen" Chinese Language Edition On May 30, 1989, the statue Goddess of Democracy was erected at Tiananmen Square and became one of the lasting symbols of the 1989 student movement. The following is a re-telling of the making of that statue, originally published in the book Children of Dragon, by a sculptor named Cao Xinyuan: Nothing excites a sculptor as much as seeing a work of her own creation take shape. But although I was watching the creation of a sculpture that I had had no part in making, I nevertheless felt the same excitement. It was the "Goddess of Democracy" statue that stood for five days in Tiananmen Square. Until last year I was a graduate student at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, where the sculpture was made. I was living there when these events took place. 点击图像去Amazon购买 Students and faculty of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, which is located only a short distance from Tiananmen Square, had from the beginning been actively involved in the demonstrations. -

Amnesty International

amnesty international PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA No Improvement in Human Rights: The Imprisonment of dissidents in 1998 4 March 1999 AI Index: ASA 17/14/99 Despite the marking of the 50th anniversary of the adoption of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights in 1998 and despite the recent signing by China of the two United Nations Covenants on Human Rights there are still no guarantees for the Chinese people that they will not be detained or arrested for seeking the freedoms of association and expression enshrined in the UN Declaration. In the past twelve months, many scores of people throughout China have been detained, harassed and imprisoned solely for exercising these rights. The Chinese government’s signing of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) in October 1998, the visits to China of American President Bill Clinton, and the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Mary Robinson were heralded as triumphs for diplomacy and human rights ‘dialogue’. International opinion began to suggest that the Chinese authorities were making improvements in human rights. However, as the prospect of international censure recedes and the international spotlight faded, the Chinese authorities once again began to crack down on dissidents and activists. During the last few weeks of 1998, over 29 dissidents were detained, four leading dissidents sentenced to lengthy terms of imprisonment and several other dissidents and labour activists have been sentenced to re-education through labour terms and lengthy terms of imprisonment. Since October 1998 when China signed the ICCPR it is estimated that over 80 dissidents have been detained and at least 15 high profile dissidents have been given heavy prison sentences or assigned to re-education through labour. -

Han Dongfang: from Tiananmen Hero to Modest Workers' Champion

48 autumn-winter 2014/HesaMag #10 Books 1/2 Han Dongfang: from Tiananmen hero to modest workers’ champion Don’t, whatever you do, call him a dissident. commenting on working conditions in China But there is still a long and challenging Hero of Tiananmen Square he may be, but he from his cramped studio. But he got bored road ahead. Industrial development has put won’t be labelled that way – too intellectual, with it not being connected to workface real- the environment and workers’ health at risk. too highbrow. Han Dongfang always remem- ities. "I was just an editorializing journalist, "Most of the cases we have taken up in the bers that before the spring 1989 protests he never getting out of the office and doing noth- past two years concern work-related accidents was a railway worker. And who with a name ing but commenting," he now says. and diseases," he says. Silicosis is wreaking like Dongfang – meaning "the East" in refer- So he persuaded Radio Free Asia to set havoc, affecting more than six million work- ence to The East is Red, China’s anthem dur- up a direct chat line with workers in all re- ers – miners, naturally, but also workers in ing the Cultural Revolution – could set them- gions of China. "These weekly talks helped the building trades, cement works, jewellery selves up as a counter-revolutionary? me understand how Chinese workers live manufacture, etc. To help them claim com- No, Han Dongfang was never a self-ap- and what they go through every day. They let pensation, the China Labour Bulletin sends pointed Lech Walesa of the Far East. -

Wikileaks Advisory Council

1 WikiLeaks Advisory Council 2 Hi everyone, My name is Tom Dalo and I am currently a senior at Fairfield. I am very excited to Be chairing the WikiLeaks Advisory Council committee this year. I would like to first introduce myself and tell you a little Bit about myself. I am from Allendale, NJ and I am currently majoring in Accounting and Finance. First off, I have been involved with the Fairfield University Model United Nations Team since my freshman year when I was a co-chair on the Disarmament and International Security committee. My sophomore year, I had the privilege of Being Co- Secretary General for FUMUN and although it was a very time consuming event, it was truly one of the most rewarding experiences I have had at Fairfield. Last year I was the Co-Chair for the Fukushima National Disaster Committee along with Alli Scheetz, who filled in as chair for the committee as I was unaBle to attend the conference. Aside from my chairing this committee, I am currently FUMUN’s Vice- President. In addition to my involvement in the Model UN, I am a Tour Ambassador Manager, and a Beta Alpha Psi member. I love the outdoors and enjoy skiing, running, and golfing. I am from Allendale, NJ and I am currently majoring in Accounting and Finance. Some of you may wonder how I got involved with the Model United Nations considering that I am a business student majoring in Accounting and Finance. Model UN offers any student, regardless of their major, a chance to improve their puBlic speaking, enhance their critical thinking skills, communicate Better to others as well as gain exposure to current events. -

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices 2003: China (Includes Tibet, Hong Kong and Macau)

Page 1 of 66 China (includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau) Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2003 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 25, 2004 (Note: Also see the section for Tibet, the report for Hong Kong, and the report for Macau.) The People's Republic of China (PRC) is an authoritarian state in which, as directed by the Constitution, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP or Party) is the paramount source of power. Party members hold almost all top government, police, and military positions. Ultimate authority rests with the 24-member political bureau (Politburo) of the CCP and its 9-member standing committee. Leaders made a top priority of maintaining stability and social order and were committed to perpetuating the rule of the CCP and its hierarchy. Citizens lacked both the freedom peacefully to express opposition to the Party-led political system and the right to change their national leaders or form of government. Socialism continued to provide the theoretical underpinning of national politics, but Marxist economic planning has given way to pragmatism, and economic decentralization increased the authority of local officials. The Party's authority rested primarily on the Government's ability to maintain social stability; appeals to nationalism and patriotism; Party control of personnel, media, and the security apparatus; and continued improvement in the living standards of most of the country's 1.3 billion citizens. The Constitution provides for an independent judiciary; however, in practice, the Government and the CCP, at both the central and local levels, frequently interfered in the judicial process and directed verdicts in many high-profile cases. -

Digital Authoritarianism and the Global Threat to Free Speech Hearing

DIGITAL AUTHORITARIANISM AND THE GLOBAL THREAT TO FREE SPEECH HEARING BEFORE THE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 26, 2018 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available at www.cecc.gov or www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 30–233 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 VerDate Nov 24 2008 12:25 Dec 16, 2018 Jkt 081003 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\USERS\DSHERMAN1\DESKTOP\VONITA TEST.TXT DAVID CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Senate House MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Chairman CHRIS SMITH, New Jersey, Cochairman TOM COTTON, Arkansas ROBERT PITTENGER, North Carolina STEVE DAINES, Montana RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio TODD YOUNG, Indiana TIM WALZ, Minnesota DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TED LIEU, California JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon GARY PETERS, Michigan ANGUS KING, Maine EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Not yet appointed ELYSE B. ANDERSON, Staff Director PAUL B. PROTIC, Deputy Staff Director (ii) VerDate Nov 24 2008 12:25 Dec 16, 2018 Jkt 081003 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 C:\USERS\DSHERMAN1\DESKTOP\VONITA TEST.TXT DAVID C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS Page Opening Statement of Hon. Marco Rubio, a U.S. Senator from Florida; Chair- man, Congressional-Executive Commission on China ...................................... 1 Statement of Hon. Christopher Smith, a U.S. Representative from New Jer- sey; Cochairman, Congressional-Executive Commission on China .................. 4 Cook, Sarah, Senior Research Analyst for East Asia and Editor, China Media Bulletin, Freedom House ..................................................................................... 6 Hamilton, Clive, Professor of Public Ethics, Charles Sturt University (Aus- tralia) and author, ‘‘Silent Invasion: China’s Influence in Australia’’ ............ -

Tiananmen Square

The Tiananmen Legacy Ongoing Persecution and Censorship Ongoing Persecution of Those Seeking Reassessment .................................................. 1 Tiananmen’s Survivors: Exiled, Marginalized and Harassed .......................................... 3 Censoring History ........................................................................................................ 5 Human Rights Watch Recommendations ...................................................................... 6 To the Chinese Government: .................................................................................. 6 To the International Community ............................................................................. 7 Ongoing Persecution of Those Seeking Reassessment The Chinese government continues to persecute those who seek a public reassessment of the bloody crackdown. Chinese citizens who challenge the official version of what happened in June 1989 are subject to swift reprisals from security forces. These include relatives of victims who demand redress and eyewitnesses to the massacre and its aftermath whose testimonies contradict the official version of events. Even those who merely seek to honor the memory of the late Zhao Ziyang, the secretary general of the Communist Party of China in 1989 who was sacked and placed under house arrest for opposing violence against the demonstrators, find themselves subject to reprisals. Some of those still targeted include: Ding Zilin and the Tiananmen Mothers: Ding is a retired philosophy professor at -

1989 Tiananmen Square: a Proto-History

1989 Tiananmen Square: A Proto-History Karman Miguel Lucero April 4th, 2011 Thesis Seminar Professor: Mae M. Ngai Second Reader: Dorothy Ko Word Count: 19,883 1 Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the advice, wisdom, and assistance of several individuals. I would like to thank my fellow students at Tsinghua University for providing me with source materials and assisting me in developing my own historical consciousness. Furthermore, I would like to thank Professors Tang Shaojie and Hu Weixi, not for their direct involvement with this project, but for their inspiring commitment to academic integrity and dedication to the wonderful possibilities that can result from receiving a good education. I owe much gratitude to Columbia Professor Lydia Liu, who not only offered her invaluable advice, but also provided me access to sources that are a critical component of this paper. Thank you to Ouyang Jianghe for his time and wisdom as well as to Qin Wuming (pseudonym), for letting me read his deeply moving essay. A special thank you goes to Mae M. Ngai, my senior thesis seminar professor, who has helped me throughout this process and shared in the excitement. Thank you to Dorothy Ko and Lisa J. Lucero for their priceless feedback and to Madeleine Zelin and Andrew Nathan for their advice. The passion and integrity of my various history teachers and professors have inspired me and contributed a great deal to my appreciation of history. Thank you in particular to Liu Lu, Volker R. Berghahn, and Gray Tuttle at Columbia University , each of whom really inspired my appreciation for the craft of history. -

The Political Repression of Chinese Students After Tiananmen A

University of Nevada, Reno “To yield would mean our end”: The Political Repression of Chinese Students after Tiananmen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by Katherine S. Robinson Dr. Hugh Shapiro/Thesis Advisor May, 2011 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by KATHERINE S. ROBINSON entitled “To Yield Would Mean Our End”: The Political Repression Of Chinese Students After Tiananmen be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Hugh Shapiro, Ph.D, Advisor Barbara Walker, Ph.D., Committee Member Jiangnan Zhu, Ph.D, Graduate School Representative Marsha H. Read, Ph. D., Associate Dean, Graduate School May, 2011 i ABSTRACT Following the military suppression of the Democracy Movement, the Chinese government enacted politically repressive policies against Chinese students both within China and overseas. After the suppression of the Democracy Movement, officials in the Chinese government made a correlation between the political control of students and the maintenance of political power by the Chinese Communist Party. The political repression of students in China resulted in new educational policies that changed the way that universities functioned and the way that students were allowed to interact. Political repression efforts directed at the large population of overseas Chinese students in the United States prompted governmental action to extend legal protection to these students. The long term implications of this repression are evident in the changed student culture among Chinese students and the extensive number of overseas students who did not return to China. -

The Legacy of Tiananmen: 20 Years of Oppression, Activism and Hope Chrd

THE LEGACY OF TIANANMEN: 20 YEARS OF OPPRESSION, ACTIVISM AND HOPE CHRD Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD) Web: Hhttp://crd-net.org/H Email: [email protected] THE LEGACY OF TIANANMEN: 20 YEARS OF OPPRESSION, ACTIVISM AND HOPE Chinese Human Rights Defenders June 1, 2009 Twenty years since the Tiananmen massacre, the Chinese government refuses to accept responsibility, much less apologize or offer compensation, for killing, injuring, imprisoning and persecuting individuals for participating in peaceful protests. The number of the victims, and their names and identities, remain unknown. Families continue to be barred from publicly commemorating and seeking accountability for the death of their loved ones. Activists are persecuted and harassed for independently investigating the crackdown or for calling for a rectification of the government’s verdict on the pro‐democracy movement. Many individuals continue to suffer the consequences of participating in the pro‐democracy movement today. At least eight individuals remain imprisoned in Beijing following unfair trials in which they were convicted of committing “violent crimes”. Those who were released after long sentences have had difficulty re‐integrating into society as they suffer from continued police harassment as well as illnesses and injuries resulting from torture, beatings and mistreatment while in prison. Many of those injured have had to pay for their own medical expenses and continue to struggle as the physical and psychological scars leave them unable to take care of themselves or to work. Some who took part in the protests still find it difficult to make ends meet after they were dismissed from comfortable jobs or expelled from universities after 1989.