The Semiotics of Photographic Evidence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remembering Katie Reich

THE M NARCH Volume 18 Number 1 • Serving the Archbishop Mitty Community • Oct 2008 Remembering Katie Reich Teacher, Mentor, Coach, Friend Katie Hatch Reich, beloved Biology and Environmental Science teacher and cross-country coach, was diagnosed with melanoma on April 1, 2008. She passed away peacefully at home on October 3, 2008. While the Mitty community mourns the loss of this loving teacher, coach, and friend, they also look back in remembrance on the profound infl uence Ms. Reich’s life had on them. “Katie’s passions were apparent to all “We have lost an angel on our campus. “My entire sophomore year, I don’t think “Every new teacher should be blessed to who knew her in the way she spoke, her Katie Reich was an inspiration and a mentor I ever saw Ms. Reich not smiling. Even after have a teacher like Katie Reich to learn from. hobbies, even her key chains. Her personal to many of our students. What bothers me is she was diagnosed with cancer, I remember Her mind was always working to improve key chain had a beetle that had been encased the fact that so many of our future students her coming back to class one day, jumping up lessons and try new things. She would do in acrylic. I recall her enthusiasm for it and will never have the opportunity to learn on her desk, crossing her legs like a little kid anything to help students understand biology wonder as she asked me, “Isn’t it beautiful?!” about biology, learn about our earth, or learn and asking us, “Hey! Anyone got any questions because she knew that only then could she On her work keys, Katie had typed up her about life from this amazing person. -

Connections Equity, Opportunity and Inclusion for People with Disabilities Since 1975

Connections Equity, Opportunity and Inclusion for People with Disabilities since 1975 Volume 41 w Issue 4 w Winter 2016 Agency Transformation In This Issue 5 The Role of Agency and Systems Transformation in Supporting “One Person at A Time” Lifestyles and Supports, by Guest Editor Michael Kendrick 8 The Transformation of Amicus: Our Story, by Ann-Maree Davis, Chief Executive Officer, Amicus 12 Muiriosa Foundation: Our Journey with Person-Centred Options, by Brendan Broderick, CEO, Muiriosa Foundation 16 Our Transformation as an Organization, by Christopher Liuzzo, Associate Executive Director (Ret.), the Arc of Rensselaer County, New York 20 Dane County, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and Individualized Services, by Dennis Harkins, with Monica Bear and Dan Rossiter 25 The Story of KFI’s Agency Transformation, by Gail Fanjoy 28 Transformational Change in Avalon (BOP) Inc: “Don’t look back we are not going that way”, by Helen Brownlie 36 Spectrum: The Story Of Our Journey, by Susan Stanfield, Spectrum Society for Community Living 2016 TASH Conference, Page 41 Chapter News, Page 43 SAVE THE DATE FOR THE 2017 TASH CONFERENCE Each year, the TASH Conference strengthens the disability field by connecting attendees to inno- vative information and resources, facilitating connections between stakeholders within the dis- ability movement, and helping attendees reignite their passion for an inclusive world. The 2017 TASH Conference will focus on transformation in all aspects of life and throughout the lifespan. We look forward to -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Beyond Lip Service on Mutual Learning

Beyond lip service on mutual learning: The potential of CSO and think-tank partnerships for transforming Rising Powers’ contributions to sustainable development Alex Shankland and Jennifer Constantine Institute of Development Studies, UK Introduction1 society organisations based in Rising Power countries with think-tanks and other academic actors from those countries and from the global As the introduction to this report puts it, North. We conclude by highlighting some of the “‘partnership’ has become a buzzword in the potential contributions that such partnerships global arena.” Given this context, the Global could make in a post-2015 era, where the principle Partnership for Effective Development of universality will challenge donor-recipient Cooperation (GPEDC), which was launched in dichotomies and where knowledge exchange will late 2011 and held its first High-Level Meeting be as important as financial flows in achieving in Mexico City in April 2014, should have been effective development cooperation. ideally positioned to make a difference. In particular, the GPEDC held out the promise of significant progress in two key areas of From Busan to Mexico partnership. The first was between the donors (mainly Northern countries) aligned with the The GPEDC emerged from the 2011 Busan High OECD-DAC, and the ‘Rising Power’ exponents Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness, whose final of South-South Cooperation.2 The second was declaration saw a range of commitments that between governments and non-state actors seemed to hold genuine promise for efforts to in both the North and South – with the latter make the rhetoric of mutual learning and multi- including both civil society organisations (CSOs) stakeholder partnership a reality. -

Sanbio Business Plan 2014–2018 Sanbio

SANBio Business Plan 2014–2018 SANBio SANBio Business Plan 2014–2018 Business Plan 2013–2018 Contents Contents 1 PAGE NOS TO Acronyms 3 BE UPDATED Executive Summary 4 Sumário Executivo 4 CHAPTER 1 SANBio Strategic Objectives 9 1.1 Background 9 1.1.1 Rationale for the Business Plan 9 1.1.2 SANBio has made significant progress 10 1.1.3 International Cooperation Partner support 12 1.1.4 Challenges remaining 12 1.1.5 Business Plan outline 12 1.2 Vision and Strategy 13 1.3 Mission, Core Functions and Expected Outputs 13 CHAPTER 2 Situational Analysis 15 2.1 Global Context 15 2.1.1 Over view 15 2.1.2 Global Biosciences industry 15 2.1.3 Global R&D spending 15 2.2 African Context 15 2.2.1 Overview 15 2.2.2 R&D investment in Africa 16 2.2.3 Human capacity development 16 2.2.4 Private-sector involvement 17 2.3 SADC Regional Context 15 2.3.1 Overview 16 2.3.2 R&D investment in SADC region 16 2.3.3 Innovation Systems in Southern Africa 16 2.3.4 Human capacity development 16 2.3.5 International Cooperation Partners 16 2.3.6 Collaberation 15 2.4 African Context 15 2.4.1 AU Nepad policies and priorities 20 2.4.2 SADC Policy Framework and priority areas 20 2.4.3 National development strategies 22 2.5 Themes Emerging from Situational Analysis 22 SANBIO BUSINESS PLAN 2013 – 2018 1 CHAPTER 3 Business Model 24 3.1 Guiding Principles 24 3.1.1 A transparent collaborative, regionally-focussed initiative 24 3.1.2 ‘Hub-Node’ Network Model 25 3.1.3 Committed to the active participation of key stakeholders 25 3.1.4 Demand-driven 25 3.1.5 Results-oriented 25 3.1.6 -

Local Volleyball Centralia Printing a Cappella at Centralia College

Mill Lane Winery: New Winery Opens Tomorrow in Tenino / Main 14 Cowlitz Wildlife Refuge Kosmos Release Site Fosters Pheasant Hunting Fun / Sports: Outdoors $1 Midweek Edition Thursday, Sept. 27, 2012 Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com Mossyrock Park Advocate Wins Statewide Award / Main 3 Centralia Printing Historic Downtown Building to Sell Inventory, A Cappella at Repurpose as Apartments and Offices / Centralia College Local Volleyball Main 12 LC Concerts to Host Vocalists / Life: A&E Scores & Stats / Sports Tumultuous Tenino Recalls, Scandal, Illegal Use of Office and the State of Affairs in a Once Quiet Thurston County Town By Kyle Spurr “I didn’t break any laws,” [email protected] Strawn told the audience Tues- day night. “I probably broke a ‘‘Integrity has been compromised across the board.’’ TENINO — Residents of this few people’s support.” once quiet city spoke up Tuesday While the mayor defends his Wayne Fournier Tenino City Councilor night as a standing-room only innocence, Councilor Robert crowd challenged the city council Scribner was discovered to have for bringing consistent controver- used resources when working at sy to the south Thurston County the Washington State Depart- town over the past eight months. ment of Labor and Industries in ‘‘I didn’t break any laws. I probably broke a In the past two weeks alone, June to access personal and con- the city’s mayor, Eric Strawn, fidential records on the mayor few people’s support.’’ was accused of having sexual and other city employees, ac- Eric Strawn contact with a woman inside a cording to internal investigation city vehicle, but did not face any Mayor of the City of Tenino charges for the incident. -

GE^EN HLAND Design • Installation • Maintenance • Tree Work

DELINQUENT The islands' newspaper TAX of record NOTICES i Where to find the lists • see page 19 Week of May 6 - 12,2004 SANiBEL & CAPTIVA, FLORIDA VOLUME 31, NUMBER 19, 24 PAGES 75 CENTS Feeding alligators still a problem on Sanibel Jenny Burnham approached the officer. The state wildlife Staff Writer officer made a determination that Gates was aggressive, and contacted the Sanibei His nickname was "'Gates,'" and he was Police Department. The Police always there, sunning himself on a bank Department responded with assistance, as not far from the entrance to Gulf Pines off they are required to do. A state-licensed the Sanibel-Captiva Road. He had lived at trapper was summoned and used a cross- Gulf Pines for most of his life, and he was bow to kill Gates. "kind of a mascot to some people'" in the The villain in this story is not the Fish community, according to resident John and Wildlife Commission, nor is it the Elting. Sanibel Police Department. The villain But Gates died, not because of disease, here is the person who ignored clearly or poachers. Gates lost his life because an posted warnings noi to feed the alligators. unknown person tossed him some tidbits This is the person who really killed of food. Gates. According to the City of Sanibel According to the Florida Fish and Alligator Management Program, wild Wildlife Conservation Commission, "by alligators, even big ones, fear humans and tossing scraps to alligators, people actual- will move away when approached. Any ly teach the reptiles to associate people alligator on land that does not retreat, or with food.'" and alligators seldom attack that approaches at the sight oi" humans, is humans for any reason other than food. -

Hail the Queen

ThE QLIEEN? BY TAMARA WINFREY HARRIS ILLUSTRATIONS RYIRANA DOUER What do our perceptions of Bejonce'sfeminism say about us? Who run the world? If entertainment domination is the litmus test, then all hail Queen Bey. Beyoncé. She who, in the last few months alone, whipped her golden lace-front and shook her booty fiercely enough to zap the power in the Superdome (electrical relay device, bah!); produced, directed, and starred in Life Is Buta Dream, HBO's most-watched documentary in nearly a decade; and launched the Mrs. Carter Show—the must-see concert of the summer. Beyoncé's success would seem to offer many reasons But some pundits are hesitant to award the for feminists to cheer. The performer has enjoyed singer feminist laurels. For instance, Anne Helen record-breaking career success and has taken con- Petersen, writer for the blog Celebrity Gossip, trol of a multimillion-dollar empire in a male-run Academic Style (and Bitch contributor), says, industry, while being frank about gender inequities "What bothers me—what causes such profound and the sacrifices required of women. She employs ambivalence—is the way in which [Beyoncé has] an all-woman band of ace musicians—the Sugar been held up as an exemplar of female power and, Mamas—that she formed to give girls more musical by extension, become a de facto feminist icon.... role models. And she speaks passionately about the Beyoncé is powerful. F-cking powerful. And that, power of female relationships. in truth, is what concerns me." SUMMER.13 I ISSUE NO.59 bítCh I 29 Petersen says the singer's lyrical feminism In a January 2013 Guardian article titled "Beyoncé: Being Photographed in Your swings between fantasy ("Run the World [Girls]") Underwear Doesn't Help Feminism," writer Hadley Freeman blasts the singer for posing and "bemoaning and satirizing men's inability to in the February issue of GQ "nearly naked in seven photos, including one on the cover in commit to monogamous relationships" ("Single which she is wearing a pair of tiny knickers and a man's shirt so cropped that her breasts Ladies"). -

Skate Life: Re-Imagining White Masculinity by Emily Chivers Yochim

/A7J;(?<; technologies of the imagination new media in everyday life Ellen Seiter and Mimi Ito, Series Editors This book series showcases the best ethnographic research today on engagement with digital and convergent media. Taking up in-depth portraits of different aspects of living and growing up in a media-saturated era, the series takes an innovative approach to the genre of the ethnographic monograph. Through detailed case studies, the books explore practices at the forefront of media change through vivid description analyzed in relation to social, cultural, and historical context. New media practice is embedded in the routines, rituals, and institutions—both public and domestic—of everyday life. The books portray both average and exceptional practices but all grounded in a descriptive frame that ren- ders even exotic practices understandable. Rather than taking media content or technol- ogy as determining, the books focus on the productive dimensions of everyday media practice, particularly of children and youth. The emphasis is on how specific communities make meanings in their engagement with convergent media in the context of everyday life, focusing on how media is a site of agency rather than passivity. This ethnographic approach means that the subject matter is accessible and engaging for a curious layperson, as well as providing rich empirical material for an interdisciplinary scholarly community examining new media. Ellen Seiter is Professor of Critical Studies and Stephen K. Nenno Chair in Television Studies, School of Cinematic Arts, University of Southern California. Her many publi- cations include The Internet Playground: Children’s Access, Entertainment, and Mis- Education; Television and New Media Audiences; and Sold Separately: Children and Parents in Consumer Culture. -

From American Bandstand to Total Request Live: Teen Culture and Identity on Music Television Kaylyn Toale Fordham University, [email protected]

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham American Studies Senior Theses American Studies 2011 From American Bandstand to Total Request Live: Teen Culture and Identity on Music Television Kaylyn Toale Fordham University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/amer_stud_theses Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Toale, Kaylyn, "From American Bandstand to Total Request Live: Teen Culture and Identity on Music Television" (2011). American Studies Senior Theses. 14. https://fordham.bepress.com/amer_stud_theses/14 This is brought to you for free and open access by the American Studies at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Studies Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From American Bandstand to Total Request Live : Teen Culture and Identity on Music Television Kaylyn Toale American Studies Senior Thesis Fall 2010 Prof. Amy Aronson, Prof. Edward Cahill Toale 1 “When we started the show… there weren’t any teenagers,” remarked Dick Clark to The Washington Post in 1977. “They were just miniatures of their parents. They didn’t have their own styles. They didn’t have their own music. They didn’t have their own money. And now, of course, the whole world is trying to be a kid.” 1 The show to which he refers, of course, is American Bandstand, which paved the way for Total Request Live (TRL) and other television shows which aimed to distribute popular music to young audiences. Here, Dick Clark situates the intersection of music and television as an entity that provides great insight into the social dynamics, the media experience, and the very existence of teenagers in the United States. -

The Effects of Hip-Hop and Rap on Young Women in Academia

The Effects of Hip-Hop and Rap on Young Women in Academia by Sandra C Zichermann A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education Sociology in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Sandra C Zichermann 2013 The Effects of Hip-Hop and Rap on Young Women in Academia Sandra C Zichermann Doctor of Education Sociology in Education University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This thesis investigates the rise of the cultures and music of hip-hop and rap in the West and its effects on its female listeners and fans, especially those in academia. The thesis consists of two parts. First I conducted a content analysis of 95 lyrics from the book, Hip-Hop & Rap: Complete Lyrics for 175 Songs (Spence, 2003). The songs I analyzed were performed by male artists whose lyrics repeated misogynist and sexist messages. Second, I conducted a focus group with young female university students who self-identify as fans of hip-hop and/or rap music. In consultation with my former thesis supervisor, I selected women enrolled in interdisciplinary programmes focused on gender and race because they are equipped with an academic understanding of the potential damage or negative effects of anti-female or negative political messaging in popular music. My study suggests that the impact of hip-hop and rap music on young women is both positive and negative, creating an overarching feeling of complexity for some young female listeners who enjoy music that is infused with some lyrical messages they revile. -

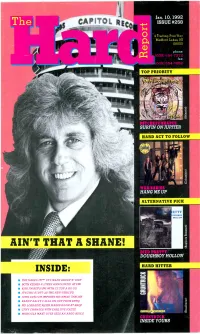

Ain't That a Shane!

Jan. 10, 1992 CAPITOL R ISSUE #258 0 4 Trading Post Way fai Medford Lakes, NJ 08055 phone: (609) 654-7272 fax: (ROMPR4-6852 TOP PRIORITY HARD ACT TO FOLLOW ALTERNATIVE PICK ',ETTY OUGHBOY 1101.1.0W AIN'T THAT A SHANE! INSIDE: HARD HITTER II THE NAKED CIT7' UTZ MADE GROUP W VEEP III BOTH KEINER & ..YKES ANNOUNCED AT EMI KISS FM RETURNS WITH ZZ TOP A GC GO IT'S ERIC STOTT AS THE NEW WXRC FD JOHN DUNTi-LN DEPARTS HIS WMAD THRONE IN RANDY RALEI. F )LLS ON OUT FROM KFMQ MD LORRAINE MCIER MAKES ROOM AT KRQF CFNY CHANGES KITH EARL JIVE JOLTED MISSOULA MA Kr OVER SEES AN ARGO ADIC S 0.111M11,1111 INSIDE YOURS NAG MANAGEMENT: ARTISTSHORIZON SERVICES ENTERTAINMENT CORP. Hard Hundred Lw Tw Artist Track LwTw Artist Track 1 1 U2 "Mysterious Ways" 32 51 Ozzy Osbourne "No More Tears" 2 2VAN HALEN "Right Now" 26 52The Who "Saturda Ni ht's ..." 4 3JOHN MELLENCAMP "Love And ..." >> D 53UGLY KID JOE "Everything About ..." 6 4BRYAN ADAMS "There Will Never ..." 62 54 U2 "Who's Gonna Ride..." 20 5GENESIS "I Can't Dance" 83 55 DIRE STRAITS "The Bug" 8 6NIRVANA "Smells Like Teen ..." >> D56 RTZ "Until Your Love ..." 18 7TOM PETTY "Kings Highway" 40 57 Lynyrd Skyrd "All I Can Do ..." 9 8 GUNS N' ROSES "November Rain" 63 58 GENESIS - "Jesus He Knows..." 12 9EDDIE MONEY "She Takes My ..." 66 59JAMES REYNE "Some People" 13 10BOB SEGER "Take A Chance" 69 60 DRAMARAMA "Haven't Got A ..." 10 11 METALLICA "The Unforgiven" 72 61 VINNIE MOORE "Meltdown" 3 12 Stevie Ray Vaughan "The Sky Is.