Trevor Burnard HEARING SLAVES SPEAK with an Introduction by Trevor Burnard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Netherlands the Netherlands Despite Being a Small Country, Lacking

Netherlands The Netherlands despite being a small country, lacking in natural resources, was able in the 17th Century to become the centre for European overseas trade, including the trade in human beings. This 'Dutch Miracle' was a product of numerous innovations in navigation, manufacturing and finance, which allowed for slaves and slave produce to be transported at greater capacity and at lower cost. The first recorded trader sold 20 Africans to the colony of Virginia in North America in 1619, but the Dutch trade only really took off in response to labour shortage in the newly conquered sugar plantations of Northern Brazil in 1630. Wars with Portugal (1620-1655) left the Dutch in control of many of the slave depots on the West African coast, centred on modern Ghana, which by 1650 had dispatched 30,000 slaves to Brazil alone. After the return of the Brazilian colonies to Portugal in 1654, the Dutch traders were able to draw upon their network of forts to supply other European powers, dominating the supply to Spain until the 1690s. However the near constant warfare the Netherlands were waged in with other European nations, such as Spain, France and Britain, by Imperial Spain, did eventually sap its strength, and Dutch involvement in the trade declined in the 18th Century, and effectively ceased in 1795. When the final abolition of the trade and institution of slavery formally occurred in 1863, Dutch agents had brought 540,000 Africans to the Americas and cast the spectre of slavery east, from the Cape of Good Hope to the Indonesian archipelago. -

Interactive Reader and Study Guide

Interactive Reader and Study Guide HOLT Social Studies United States History Beginnings to 1877 Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any informa- tion storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Teachers using HOLT SOCIAL STUDIES: UNITED STATES HISTORY may photocopy com- plete pages in sufficient quantities for classroom use only and not for resale. HOLT and the “Owl Design” are registered trademarks licensed to Holt, Rinehart and Winston, registered in the United States of America and/or other jurisdictions. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-03-042643-X 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 082 08 07 06 05 Contents Chapter 1 The World before the Opening Chapter 8 The Jefferson Era of the Atlantic Chapter Opener with Graphic Organizer . 66 Chapter Opener with Graphic Organizer . 1 Sec 8.1 . 67 Sec 1.1 . 2 Sec 8.2 . 69 Sec 1.2 . 4 Sec 8.3 . 71 Sec 1.3 . 6 Sec 8.4 . 73 Sec 1.4 . 8 Chapter 9 A New National Identity Chapter 2 New Empires in the Americas Chapter Opener with Graphic Organizer . 75 Chapter Opener with Graphic Organizer . 10 Sec 9.1 . 76 Sec 2.1 . 11 Sec 9.2 . 78 Sec 2.2 . 13 Sec 9.3 . 80 Sec 2.3 . 15 Chapter 10 The Age of Jackson Sec 2.4 . 17 Chapter Opener with Graphic Organizer . 82 Sec 2.5 . -

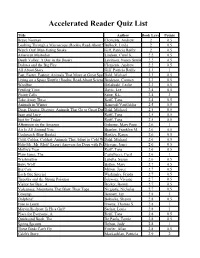

Accelerated Reader Quiz List

Accelerated Reader Quiz List Title Author Book Level Points Brave Norman Clements, Andrew 2 0.5 Looking Through a Microscope (Rookie Read-About Science)Bullock, Linda 2 0.5 Watch Out! Man-Eating Snake Giff, Patricia Reilly 2 0.5 American Mastodon Lindeen, Carol K. 2.2 0.5 Death Valley: A Day in the Desert Levinson, Nancy Smiler 2.2 0.5 Dolores and the Big Fire Clements, Andrew 2.2 0.5 All About Stacy Giff, Patricia Reilly 2.3 1 Fast, Faster, Fastest: Animals That Move at Great SpeedsDahl, Michael 2.3 0.5 Living on a Space Shuttle (Rookie Read-About Science)Bredeson, Carmen 2.3 0.5 Woolbur Helakoski, Leslie 2.3 0.5 Feeding Time Davis, Lee 2.4 0.5 Phone Calls Stine, R.L. 2.4 3 Take Away Three Reiff, Tana 2.4 0.5 Animals in Winter Bancroft/VanGelder 2.5 0.5 Deep, Deeper, Deepest: Animals That Go to Great DepthsDahl, Michael 2.5 0.5 Juan and Lucy Reiff, Tana 2.5 0.5 Just for Today Reiff, Tana 2.5 0.5 Afternoon on the Amazon Osborne, Mary Pope 2.6 1 Air Is All Around You Branley, Franklyn M. 2.6 0.5 Cockroach (Bug Books) Hartley, Karen 2.6 0.5 Cold, Colder, Coldest: Animals That Adapt to Cold WeatherDahl, Michael 2.6 0.5 Help Me, Mr. Mutt! Expert Answers for Dogs with PeopleStevens, Problems Janet 2.6 0.5 Mollie's Year Reiff, Tana 2.6 0.5 Plain Janes, The Castellucci, Cecil 2.6 1 Washington Labella, Susan 2.6 0.5 Baby Wolf Batten, Mary 2.7 0.5 Big Cats Milton, Joyce 2.7 0.5 Each One Special Wishinsky, Frieda 2.7 0.5 Timothy and the Strong Pajamas Schwarz, Viviane 2.7 0.5 Visitor for Bear, A Becker, Bonny 2.7 0.5 Volcanoes: Mountains That Blow Their Tops Nirgiotis, Nicholas 2.7 0.5 Coverup Bennett, Jay 2.8 3 Dolphins! Bokoske, Sharon 2.8 0.5 Free to Learn Owens, Thomas S. -

31584 Big Brown Bear Mcphail, David 0.4 0.5 41850 Clifford Makes a Friend Bridwell, Norman 0.4 0.5 48225 Gifts for Gus: the Sound of G Ballard, Peg 0.4 0.5 31594 B

31584 Big Brown Bear McPhail, David 0.4 0.5 41850 Clifford Makes a Friend Bridwell, Norman 0.4 0.5 48225 Gifts for Gus: The Sound of G Ballard, Peg 0.4 0.5 31594 B. Bears Ride the Thunderbolt, The Berenstain, Stan 0.6 0.5 48215 Cats: The Sound of Short A Flanagan, Alice K. 0.6 0.5 9018 Foot Book, The Seuss, Dr. 0.6 0.5 48207 Fox: The Sound of X, A Flanagan, Alice K. 0.6 0.5 48224 Fun! The Sound of Short U Ballard/Klingel 0.6 0.5 48233 Little Bit: The Sound of Short I Ballard/Klingel 0.6 0.5 48208 Pet: The Sound of P, A Flanagan, Alice K. 0.6 0.5 9310 Eat Your Peas, Louise! Snow, Pegeen 0.7 0.5 48223 Four Fish: The Sound of F Flanagan, Alice K. 0.7 0.5 134214 Pigeon Wants a Puppy!, The Willems, Mo 0.7 0.5 48244 Sam: The Sound of S Flanagan, Alice K. 0.7 0.5 9367 Happy Birthday, Dear Dragon Hillert, Margaret 0.8 0.5 123748 I Will Surprise My Friend! Willems, Mo 0.8 0.5 9375 It's Halloween, Dear Dragon Hillert, Margaret 0.8 0.5 48232 Left: The Sound of L Flanagan, Alice K. 0.8 0.5 54463 Let's Go to a Fair Foley, Cate 0.8 0.5 48236 On My Boat: The Sound of Long O Noyed/Kingel, B. 0.8 0.5 48239 Play Day: The Sound of Long A Flanagan, Alice K. -

San Diego Public Library New Additions February 2007

San Diego Public Library New Additions February 2007 Juvenile Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities Compact Discs 100 - Philosophy & Psychology DVD Videos/Videocassettes 200 - Religion E Audiocassettes 300 - Social Sciences E Audiovisual Materials 400 - Language E Books 500 - Science E CD-ROMs 600 - Technology E Compact Discs 700 - Art E DVD Videos/Videocassettes 800 - Literature E Foreign Language 900 - Geography & History E New Additions Audiocassettes Fiction Audiovisual Materials Foreign Languages Biographies Large Print CD-ROMs Fiction Call # Author Title J FIC/BARROWS Barrows, Annie. Ivy + Bean and the ghost that had to go J FIC/BOOTH Booth, Martin. Soul stealer J FIC/CLEMENTS Clements, Andrew, Room one J FIC/ELLIOTT Elliott, David, Evangeline Mudd and the golden-haired apes of the Ikkinasti Jungle J FIC/GIFF Giff, Patricia Reilly. Pictures of Hollis Woods J FIC/GOSCINNY Goscinny, Nicholas again J FIC/GUTMAN Gutman, Dan. Miss Holly is too jolly! J FIC/GUTMAN Gutman, Dan. Mrs. Patty is batty! J FIC/HARRAR Harrar, George, The wonder kid J FIC/HOWE Howe, James, Howie Monroe and the doghouse of doom J FIC/JACQUES Jacques, Brian. Voyage of slaves J FIC/JOHNSON Johnson, Jane, The secret country J FIC/LA FEVERS La Fevers, R. L. The forging of the blade J FIC/LAWRENCE Lawrence, Iain, Gemini summer J FIC/LEWIS Lewis, C. S. The lion, the witch, and the wardrobe J FIC/MCCAUGHREAN McCaughrean, Geraldine. Peter Pan in scarlet J FIC/MORRISSY Morrissey, Dean. The moon robber J FIC/NIMMO Nimmo, Jenny. The snow spider J FIC/OSBORNE Osborne, Mary Pope. Night of the new magicians J FIC/POTTER Potter, Ellen, Pish Posh J FIC/SALTEN Salten, Felix, Bambi J FIC/SALTEN Salten, Felix, Bambi J FIC/STEVENSON Stevenson, Robert Louis, Kidnapped J FIC/TINGLE Tingle, Tim. -

Adventure Books Available at Green Hills Public Library

Adventure Books Available at GHPLD J 39 Clues The 39 Clues Series J Aiken, J. Dangerous Games J Aiken, J. Midwinter Nightingale J Aiken, J. The Wolves of Willoughby Chase J Appelt, K. The Underneath J Appelt, K. The Underneath AUDIOBOOK J Avi A Beginning, a Middle, and an End J Avi The End of the Beginning J Avi Poppy’s Return J Avi Poppy and Ereth J Avi The Good Dog AUDIOBOOK J Avi Windcatcher AUDIOBOOK J Baccalario, P.D. The Century Quartet series J Bauer, M.D. Runt J Birney, B. Humphrey series J Black, S. Lassie J Bond, M. A Bear Called Paddington AUDIOBOOK J Bond, M. A Bear Called Paddington J Bond, M. More About Paddington J Bond, M. Paddington Here and Now J Boniface, W. The Extraordinary Adventures of Ordinary Boy < J Bosch, P. The Name of This Book Is Secret J Bosch, P. If You’re Reading This, It’s Too Late J Bosch, P. This Isn’t What it Looks Like J Bosch, P. You Have to Stop This J Bosch, P. This Book is Not Good for You J Breathed, B. Flawed Dogs J Bright, J.E. Kung Fu Panda: The Secret of the Scroll J Brown, J. The Worldwide Adventures of Flat Stanley (7) J Brown, J. Flat Stanley His Original Adventure J Brown, J. Flat Stanley’s Worldwide Adventures (6) J Byars, B. Little Horse on His Own J Byars, B. Tornado J Byars, B. Me Tarzan J Chambers, A. Seal Secrets J Choldenko, G. Al Capone Does My Shirts J Choose Your Own Beware the Snake’s Venom J Choose Your Own Caravan J Choose Your Own Curse of the Pirate Mist J Choose Your Own Dragon Day J Choose Your Own The Haunted House J Choose Your Own Journey Under the Sea J Choose Your Own Monsters of the Deep J Choose Your Own The Trail of Lost Time J Choose Your Own Search for Dragon Queen J Choose Your Own Search for the Black Rhino J Choose Your Own Smoke Jumpers J Choose Your Own Your Grandparents are Zombies! J Choose Your Own Curse of the Pirate Mist J Choose Your Own Search for the Black Rhino J Choose Your Own The Trail of Lost Time J Choose Your Own Search for the Dragon Queen J Choose Your Own Island of Doom J Chrisman, A. -

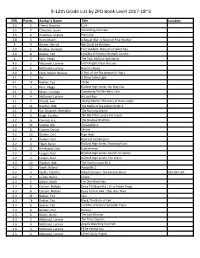

9-12Th Grade List by ZPD Book Level 2017-18~3

9-12th Grade List by ZPD Book Level 2017-18~3 ZPD Points Author's Name Title Location 3.2 5 Friend, Natasha Lush 3.5 7 Colasanti, Susan Something Like Fate 3.5 6 Hamilton, Virginia Plain City 3.8 3 Harry Mazer A Boy at War: A Novel of Pearl Harbor 4 4 Barnes, Derrick We Could be Brothers 4.0 5 Bradley, Kimberly For Freedom: Story of a French Spy 4.0 8 Dekker, Ted Lost Bks of History Series#5: Lunatic 4 3 Kern, Peggy The Test, Bluford High Series 4.0 5 McDaniel, Lurlene Until Angels Close my Eyes 4.0 5 McDaniel, Lurlene Heart to Heart 4.0 4 Peck, Robert Newton A Part of the Sky (sequel to Pigs ) 4.1 5 Avi A Place Called Ugly 4.1 14 Dekker, Ted Thr3e 4.1 3 Kern, Peggy Bluford High Series: No Way Out 4.1 4 Mazer, Lerangis Somebody Tell Me Who I Am 4.1 4 McDaniel, Lurlene Hit and Run 4.1 7 Rinaldi, Ann Taking Liberty: The Story of Oney Judge 4.1 12 Riordan, Rick The Battle of the Labyrinth Bk 4 4.1 9 Van Draanen, Wendelin The Running Dream 4.1 9 Voigt, Cynthia Tell Me if the Lovers are Losers 4.2 6 Cannon, A.E. The Shadow Brothers 4.2 13 Condie, Ally Crossed Bk 2 4.2 8 Cooner, Donna Skinny 4.2 10 Deuker, Carl High Heat 4.2 8 Deuker, Carl Heart of a Champion 4.2 4 Folan, Karyn Bluford High Series: Breaking Point 4.2 12 Honeyman, Kay Interference 4.2 3 Langan, Paul Bluford High Series: Search for Safety 4.2 3 Langan, Paul Bluford High Series: The Fallen 4.2 10 Riordan, Rick The Titan’s Curse Bk 3 4.2 10 Smith, Roland Above Bk 2 4.2 5 Yeatts, Tabatha Albert Einstein: The Miracle Mind 530.092 YEA 4.2 6 Lo'pez, Diana Choke 4.3 5 Albom, Mitch For -

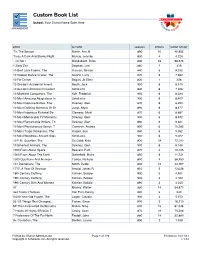

Custom Book List

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 10 40,955 'Twas A Dark And Stormy Night Murray, Jennifer 830 4 4,224 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 23 98,676 1 Zany Zoo Degman, Lori 860 1 415 10 Best Love Poems, The Hanson, Sharon 840 6 8,332 10 Coolest Dance Crazes, The Swartz, Larry 870 6 7,660 10 For Dinner Bogart, Jo Ellen 820 1 328 10 Greatest Accidental Inventi Booth, Jack 900 6 8,449 10 Greatest American President Scholastic 840 6 7,306 10 Mightiest Conquerors, The Koh, Frederick 900 6 8,034 10 Most Amazing Adaptations In Scholastic 900 6 8,409 10 Most Decisive Battles, The Downey, Glen 870 6 8,293 10 Most Defining Moments Of Th Junyk, Myra 890 6 8,477 10 Most Ingenious Fictional De Clemens, Micki 870 6 8,687 10 Most Memorable TV Moments, Downey, Glen 900 6 8,912 10 Most Remarkable Writers, Th Downey, Glen 860 6 9,321 10 Most Revolutionary Songs, T Cameron, Andrea 890 6 10,282 10 Most Tragic Romances, The Harper, Sue 860 6 9,052 10 Most Wondrous Ancient Sites Scholastic 900 6 9,022 10 P.M. Question, The De Goldi, Kate 830 18 72,103 10 Smartest Animals, The Downey, Glen 900 6 8,148 1000 Facts About Space Beasant, Pam 870 4 10,145 1000 Facts About The Earth Butterfield, Moira 850 6 11,721 1000 Questions And Answers Tames, Richard 890 9 38,950 101 Dalmatians, The Smith, Dodie 830 12 44,767 1777: A Year Of Decision Arnold, James R. -

Marlfox, Brian Jacques

Marlfox, Brian Jacques DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1qEagpj http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marlfox Queen Silth rules Castle Marl from behind the curtains of her palanquin. Greedy and vain, she has sent her six children into the world to plunder treasure. Stealth and cunning are the traits of the Marlfox. Known only in Redwall country by legend, they are said to able to appear and disappear by magic. When the strange creatures begin to appear in Mossflower Woods, it is clear that evil is abroad. A kidnapping and a cunning raid to steal the beautiful Redwall tapestry confirm the worst; Redwall is under threat! Three young friends, fated by the prophecy of Martin the Warrior, pursue the villains in a quest of daring, courage and wit to return the beloved tapestry to its home. DOWNLOAD http://t.co/af7g5fm09S http://bit.ly/1xRgKJr Outcast Of Redwall , Brian Jacques, Jan 25, 2011, Juvenile Fiction, 368 pages. Ferret Swartt Sixclaw and badger Sunflash the Mace are arch enemies who have sworn a pledge of death upon each other. Meanwhile, the Abbess of Redwall has banished a young. Mattimeo , Brian Jacques, Jul 31, 2012, Juvenile Fiction, 448 pages. Slagar the Fox is bent on revenge - and determined to bring death and destruction to Redwall Abbey. Gathering his evil band around him, Slagar plots to strike at the heart of. The Sable Quean , Brian Jacques, Feb 23, 2010, Fiction, 368 pages. Buckler the hare, Blademaster of the Long Patrol, must save the youngsters of Redwall Abbey-kidnapped by the vile Vilaya the Sable Quean-and stop the villain's conquest of. -

Hugo Grotius Pioneer of Modern International Law

The Netherlands in a Nutshell highlights from dutch history and culture Amsterdam University Press The Netherlands in a Nutshell The Netherlands in a Nutshell highlights from dutch history and culture Amsterdam University Press www.entoen.nu © 2008 Frits van Oostrom | Stichting entoen.nu isbn 978-90-8964-039-0 nur 688/840 Published by Amsterdam University Press, the Netherlands www.aup.nl Design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam, the Netherlands All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Contents 7 Foreword 9 The canon of the Netherlands 112 Main lines of the canon When we, as individuals, pick and mix cultural elements for ourselves, we do not do so indiscriminately, but according to our natures. Societies, too, must retain the ability to discriminate, to reject as well as to accept, to value some things above others, and to insist 6 on the acceptance of those values by all their members. [...] If we are to build a plural society on the foundation of what unites us, we must face up to what divides. But the questions of core freedoms and primary loyalties can’t be ducked. No society, no matter how tolerant, can expect to thrive if its citizens don’t prize what their citizenship means – if, when asked what they stand for as Frenchmen, as Indians, as Britons, they cannot give clear replies. -

Tales of Members of the Resistance and Victims of War

Come tell me after all these years your tales about the end of war Tales of members of the resistance and victims of war Ellen Lock Come tell me after all these years your tales about the end of war tell me a thousand times or more and every time I’ll be in tears. by Leo Vroman: Peace Design: Irene de Bruijn, Ellen Lock Cover picture: Leo en Tineke Vroman, photographer: Keke Keukelaar Interviews and pictures: Ellen Lock, unless otherwise stated Translation Dutch-English: Translation Agency SVB: Claire Jordan, Janet Potterton. No part of this book may be reproduced without the written permission of the editors of Aanspraak e-mail: [email protected], website: www.svb.nl/wvo © Sociale Verzekeringsbank / Pensioen- en Uitkeringsraad, december 2014. ISBN 978-90-9030295-9 Tales of members of the resistance and victims of war Sociale Verzekeringsbank & Pensioen- en Uitkeringsraad Leiden 2014 Content Tales of Members of the Resistance and Victims of War 10 Martin van Rijn, State Secretary for Health, Welfare and Sport 70 Years after the Second World War 12 Nicoly Vermeulen, Chair of the Board of Directors of the Sociale Verzekeringsbank (SVB) Speaking for your benefit 14 Hans Dresden, Chair of the Pension and Benefit Board Tales of Europe Real freedom only exists if everyone can be free 17 Working with the resistance in Amsterdam, nursery teacher Sieny Kattenburg saved many Jewish children from deportation from the Hollandsche Schouwburg theatre. Surviving in order to bear witness 25 Psychiatrist Max Hamburger survived the camps at Auschwitz and Buchenwald. We want the world to know what happened 33 in the death camp at Sobibor! Sobibor survivor Jules Schelvis tells his story. -

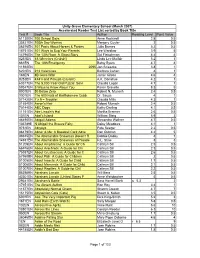

Test # Book Title Author Reading Level Point Value 61130EN 100

Unity Grove Elementary School (March 2007) Accelerated Reader Test List sorted by Book Title Test # Book Title Author Reading Level Point Value 61130EN 100 School Days Anne Rockwell 2.8 0.5 35821EN 100th Day Worries Margery Cuyler 3 0.5 56576EN 101 Facts About Horses & Ponies Julia Barnes 5.2 0.5 18751EN 101 Ways to Bug Your Parents Lee Wardlaw 3.9 5 14796EN The 13th Floor: A Ghost Story Sid Fleischman 4.4 4 8251EN 18-Wheelers (Cruisin') Linda Lee Maifair 5.2 1 661EN The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars 4.7 4 11592EN 2095 Jon Scieszka 3.8 1 6201EN 213 Valentines Barbara Cohen 4 1 166EN 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4 8252EN 4X4's and Pickups (Cruisin') A.K. Donahue 4.2 1 60317EN The 5,000-Year-Old Puzzle: Solvi Claudia Logan 4.7 1 59347EN 5 Ways to Know About You Karen Gravelle 8.3 5 8001EN 50 Below Zero Robert N. Munsch 2.4 0.5 9001EN The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubb Dr. Seuss 4 1 57142EN 7 x 9 = Trouble! Claudia Mills 4.3 1 51654EN Aaron's Hair Robert Munsch 2.4 0.5 70144EN ABC Dogs Kathy Darling 4.1 0.5 11151EN Abe Lincoln's Hat Martha Brenner 2.6 0.5 101EN Abel's Island William Steig 5.9 3 46490EN Abigail Adams Alexandra Wallner 4.7 0.5 105789E N Abigail the Breeze Fairy Daisy Meadows 4.1 1 9751EN Abiyoyo Pete Seeger 2.2 0.5 86479EN Abner & Me: A Baseball Card Adve Dan Gutman 4.2 5 86635EN The Abominable Snowman Doesn't R Debbie Dadey 4 1 14931EN The Abominable Snowman of Pasade R.L.