Fairness and Freedom: the Final Report of the Equalities Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Equality and Human Rights Commission

House of Lords House of Commons Joint Committee on Human Rights Equality and Human Rights Commission Thirteenth Report of Session 2009–10 Report, together with formal minutes and oral and written evidence Ordered by the House of Lords to be printed 2 March 2010 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 2 March 2010 HL Paper 72 HC 183 [incorporating HC 1842-i and ii of Session 2008-09] Published on 15 March 2010 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 Joint Committee on Human Rights The Joint Committee on Human Rights is appointed by the House of Lords and the House of Commons to consider matters relating to human rights in the United Kingdom (but excluding consideration of individual cases); proposals for remedial orders, draft remedial orders and remedial orders. The Joint Committee has a maximum of six Members appointed by each House, of whom the quorum for any formal proceedings is two from each House. Current membership HOUSE OF LORDS HOUSE OF COMMONS Lord Bowness Mr Andrew Dismore MP (Labour, Hendon) (Chairman) Lord Dubs Dr Evan Harris MP (Liberal Democrat, Oxford West & Baroness Falkner of Margravine Abingdon) Lord Morris of Handsworth OJ Ms Fiona MacTaggart (Labour, Slough) The Earl of Onslow Mr Virendra Sharma MP (Labour, Ealing, Southall) Baroness Prashar Mr Richard Shepherd MP (Conservative, Aldridge-Brownhills) Mr Edward Timpson MP (Conservative, Crewe & Nantwich) Powers The Committee has the power to require the submission of written evidence and documents, to examine witnesses, to meet at any time (except when Parliament is prorogued or dissolved), to adjourn from place to place, to appoint specialist advisers, and to make Reports to both Houses. -

Delga News Sept 2009

The newsletter for the Lib Dem LGBT equality group September 2009 Pride in our Performance! Marriage without Borders New LGBT Campaign Resources The 2009 Executive Your DELGA Chair Jen Yockney [email protected] needs you! As every other conference publication and training session will remind Secretary you, this is the last Autumn Conference of the Parliament with eyes Adrian Trett [email protected] turning to a general election that seems to be expected at the start of May 2010: just over seven months away. Ordinary Exec Members For DELGA we have a crucial Annual General Meeting this September, from Steph Ashley which we need to elect a team to take us through that General Election. Matt Casey Several of the existing exec will not be restanding having worked hard to get Kelvin Meyrick us back into a fighting shape - our Dave Page Secretary Adrian and our Chair Jen are both Steve Sollitt stepping down. That means we need more DELGA members like you to step forward for The exec can all be contacted on the same format of forename.familyname the team! @lgbt.libdems.org.uk email address as for the Officers The coming election will see Labour seeking to defend what we know to be a lacklustre record on LGBT issues, and the Tories trying Honorary President to pretend history began in about 2007. Evan Harris MP The Lib Dems are alone in our long and proud track record: we need you, our Vice Presidents members, to come forward whether for the Bernard Greaves Jonathan Fryer 2010 exec team or to help on specific areas Sarah Ludford MEP of work, to help proverbially shout that message from the rooftops. -

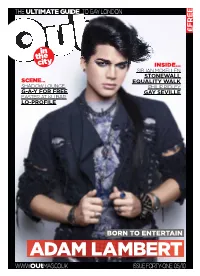

Adam Lambert

B63C:B7;/B35C723B=5/G:=<2=< 4@33 7<A723 A7@7/<;193::3< AB=<3E/:: A13<3 3?C/:7BGE/:9 A6/2=E:=C<53 >67:7>@72:3G 5/G4=@4@33 5/GA3D7::3 3/AB3@/B9C0/@ :=>@=47:3 0=@<B=3<B3@B/7< /2/;:/;03@B EEE=Cb;/51=C9 7AAC34=@BG=<3# =CbT`]\b PAGE 30 Texture and Sauterelle EDITORIAL// ADAM LAMBERT reviewed ADVERTISING PAGE 47 OUT THERE Editor Upcoming scene David Hudson highlights for May, [email protected] plus coverage of As +44 (0)20 7258 1943 One, Shadow Lounge, Staff writer Ku Bar and Lo-Profi le John O’Ceallaigh [email protected] PAGE 69 Design Concept OUTREACH Boutique Marketing London Lesbian and www.boutiquemarketing.co.uk Gay Switchboard, Graphic Designer community listings Ryan Beal plus changes in the Sub Editor laws surrounding Kathryn Fox surrogacy Contributors Adrian Foster, Edward PAGE 72 Gamlin, David Hadley, Mark OUTNEWS Palmer-Edgecumbe, David All the gay news from Perks, Max Skjönsberg, home and abroad Richard Tonks Photographer CONTENTS PAGE 78 Chris Jepson CAREER Publishers Sarah Garrett//Linda Riley PAGE 04 ISDN: 1473-6039 LETTERS Head of Advertising Send your Rob Harkavy correspondence to [email protected] [email protected] + 44 (0)20-7258 1777 Head of Business PAGE 06 Development MY LONDON Lyndsey Porter DJ and musician Larry [email protected] HUDSON’S LETTER Tee gives us his capital + 44 (0)20-7258 1777 highlights PAGE 12 Senior Advertising Executive I was wondering whether choice but to roll with it DIARY: BRAZIL! BRAZIL! Dan Goodban to write my monthly letter and make the best of a PAGE 08 [email protected] about the General Election, challenging situation. -

The 'Homophobic Hatred' Offence, Free Speech and Religious Liberty

The ‘homophobic hatred’ offence, free speech and religious liberty Clause 126 of the Criminal Justice and Immigration Bill The ‘homophobic hatred’ offence, free speech and religious liberty Clause 126 of the Criminal Justice and Immigration Bill First printed in January 2008 ISBN 978-1-901086-37-9 Published by The Christian Institute Wilberforce House, 4 Park Road, Gosforth Business Park, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE12 8DG All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of The Christian Institute. The Christian Institute is a Company Limited by Guarantee, registered in England as a charity. Company No. 263 4440, Charity No. 100 4774. Contents Incitement to ‘homophobic hatred’ 5 Tragic cases 6 The existing law 7 Inadequate safeguards 11 A realistic concern 17 A climate of fear 19 A warning from Sweden 21 Tolerance is a two way street 22 Hateful lyrics in music 24 The Bishop of Chester case: 27 can you change sexual orientation? “Temperate” language 29 The nature of religious discourse 32 Oversensitivity 34 Is this incitement law necessary? 35 Free speech amendment 37 References 39 The ‘homophobic hatred’ offence, free speech and religious liberty 4 Incitement to ‘homophobic hatred’ Clause 126 of the Criminal Justice and Immigration Bill introduces a new offence of inciting hatred on grounds of sexual orientation. The Government has set the threshold of the proposed offence at “threatening” words or behaviour and requires proof of intention to stir up hatred. -

Blue Boyz Get Their Party Invite the Conservative Party Has Embraced Its Gay Supporters in Unexpected Ways

SPECIAL Gay Tory supporters at Conference Pride in1 Manchester’s Spirit bar bulletin REPORT Blue boyz get their Party invite The Conservative Party has embraced its gay supporters in unexpected ways. David Bridle reports from last week’s Tory conference in Manchester. wonks, students and just ordinary party he transvestite at the Conference the party who disagreed with David members. Pride event in Manchester’s Spirit Cameron’s hand of friendship to his gay This year’s Conference Pride was Tbar was in high heels and a short supporters. Some of the members ar- the idea of a senior party HQ worker dress revealing a long smooth pair of gued that the party was doing it just for who received the express support of legs. I guessed he was in his late 20s. votes, but many of those traditional true David and Samantha Cameron for the ‘Have you been at the conference?’ blue ladies and gentlemen genuinely night to go ahead. It was heavily pub- I asked, thinking he might be a local welcomed the overtures. licised in the conference programme Mancunian trannie who had just come ‘We all love Matthew Parris,’ one and as delegates walked through the to see the Tory boys. lady said to me, as though the Times entrance foyer, young party workers backbencher and Labour and Liberal ‘Yes, of course,’ he said, ‘but not journalist’s years of openness about his invited them to buy tickets – alongside MP to undo the equality legislation. No dressed like this. I don’t think they’re sexuality had mellowed the blue-rinse the more traditional events. -

Parliamentary Debates House of Commons Official Report General Committees

PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT GENERAL COMMITTEES Public Bill Committee MARRIAGE (SAME SEX COUPLES) BILL Second Sitting Tuesday 12 February 2013 (Afternoon) CONTENTS Written evidence reported to the House. Examination of witnesses. Adjourned till Thursday 14 February at half-past Eleven o’clock. PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS LONDON – THE STATIONERY OFFICE LIMITED £6·00 PBC (Bill 126) 2012 - 2013 Members who wish to have copies of the Official Report of Proceedings in General Committees sent to them are requested to give notice to that effect at the Vote Office. No proofs can be supplied. Corrigenda slips may be published with Bound Volume editions. Corrigenda that Members suggest should be clearly marked in a copy of the report—not telephoned—and must be received in the Editor’s Room, House of Commons, not later than Saturday 16 February 2013 STRICT ADHERENCE TO THIS ARRANGEMENT WILL GREATLY FACILITATE THE PROMPT PUBLICATION OF THE BOUND VOLUMES OF PROCEEDINGS IN GENERAL COMMITTEES © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2013 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. Public Bill Committee12 FEBRUARY 2013 Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Bill The Committee consisted of the following Members: Chairs: †MR JIM HOOD,MR GARY STREETER † Andrew, Stuart (Pudsey) (Con) † McDonagh, Siobhain (Mitcham and Morden) (Lab) † Bradshaw, Mr Ben (Exeter) (Lab) † McGovern, Alison (Wirral South) (Lab) † Bryant, -

Runmed March 2001 Bulletin

No. 336 DECEMBER Bulletin 2003 RUNNYMEDE’S QUARTERLY revelation, so to speak, the one that A Sense of Place stood out for me was arts practitioners themselves From 24–27 November, the old Central Library building in the linking successful arts intervention projects to the utilisation of ‘social heart of Cardiff played host to the conference ‘A Sense of Place capital’ when devising and running – Displacement and Integration: the role of the arts and media in these sorts of projects. I’ll explain reshaping societies and identities in Europe’. Runnymede was one that in a moment, but first let me just step back and talk about why I of several partners facilitating this 4-day event organised by the came to this conference. British Council, and after a brief description of its aims and There are two main reasons. objectives, three active participants contribute their impressions, First, I have a strong personal belief beginning with Runnymede’s Director, Michelynn Laflèche. that it is possible to create a fairer, more just and more equal society and that I, as an individual, can ‘A Sense of Place’ was developed In preparation for this closing contribute towards creating it.This in the context of heightened public panel, we were asked to reflect on is on a very personal level, suspicion, fear and intolerance, and three questions: obviously, but it is a belief that evolving European human rights • the most memorable moment permeates all I do in all aspects of A section of the and immigration policies. Its aim of the conference for each of us my life. -

Sexismatthebbc

The creatures Love Island: A war film that will “appallingly without outlive us all watchable” heroes HEALTH & TALKING FILM P31 SCIENCE P19 POINTS P21 29TH JULY 2017 | ISSUE 1135 | £3.30 EWTHE BEST OF THE BRITISHEEK AND INTERNATIONAL MEDIA Sexism at the BBC The revolt over pay Page 2 ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT EVERYTHING THAT MATTERS www.theweek.co.uk 2 NEWS The main stories… What happened What the editorials said The BBC “fought tooth and nail” to prevent these revelations, Mind the gap said the Daily Mail, which were demanded by the Government Some of the BBC’s best-known female stars, as part of its latest Royal Charter agreement. including Clare Balding, Emily Maitlis and Fiona And no wonder. “Hard-pressed TV owners, Bruce, have called on the corporation to “act forced on pain of prosecution to pay £147 a now” to redress the glaring gap in pay between year” to keep Evans, Lineker and the like “in men and women. Salaries of 96 “creative staff” luxury”, must be furious. There is a debate to earning £150,000 or more were published last be had about “whether anybody is worth” the week. The figures showed that only a third of £2.2m that Evans is paid, said The Times. But the BBC’s highest-paid presenters are women, the “enormous disparity” between male and that its seven highest earners are all men, and female pay is “not only embarrassing for the that its best-paid man makes four times as much BBC but also clearly ridiculous”. -

On a Mission 18 October 2012 Lancaster London Hotel

Measuring Impact Absolute returns Charity fraud Impact measurement can shape alter- Absolute return strategies embraced The challenge of fraud and why an native methods of funding charities by charities have increased ten-fold anti-fraud culture can mitigate risk April/May 2012 l www.charitytimes.com Social enterprises: on a mission 18 October 2012 Lancaster London Hotel CALL FOR ENTRIES Deadline for entries 25 May 2012 Overall sponsor: The Charity Times Awards are FREE to enter and there are 23 categories this year including four new categories: International Charity, Social Investment Initiative, the Big Society Award and Consultancy of the Year. The Charity Times Awards reaches its thirteenth year in 2012 and this highly successful, popular, and growing annual gala event will be bigger and better than ever. The Charity Times Awards continue to be the pre-eminent celebration of best practice in the UK charity and not-for-profit sector. Sponsor: We recognise that it is the leaders within charities who are responsible for coordinating much of the charitable activity throughout the UK and as the engines of the charity sector; it is at this level that the Awards are targeted. For Information about Entries As such, the event itself is built around the individuals and teams for whom the Awards Andrew Holt are intended: trustees, chief executives, directors and other upper-level management T: 020 7562 2411 from not-for-profits across the UK. Reflecting this belief, the Awards provide the charity E: [email protected] sector with a dedicated event to reward the work carried out in difficult and competi- Hayley Kempen T: 020 7562 2414 tive conditions, and establishes a unique annual congress of the pre-eminent figures in E: [email protected] the sector at the premier charity event of the year. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Homosexual Identity in England, 1967-2004: Political Reform, Media and Social Change by Sebastian Charles Buckle Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2012 2 ‘There are as many ways to live as there are people in this world, and each one deserves a closer look.’ - Gully Harriet the Spy, dir. by Bronwen Hughes (Paramount Pictures, 1996) 3 4 Abstract The thesis concentrates on examining how images and representations have shaped a discourse on homosexuality, and how, in turn, this has shaped a gay and lesbian social and group identity. It explores the political, media, and social spheres to show how at any point during this period, images of homosexuality and identity were being projected in society, contributing to public ideas about sexual identity. -

Living Together

Living together British attitudes to lesbian, gay and bisexual people in 2012 Stonewall Living Together 1 Introduction Britain’s legislative protections for gay people now make it a beacon around the world and Stonewall is proud to have been instrumental in securing many of those legal advances. However, we only need to look at some of the deeply offensive comments made by senior clerics about gay people recently - likening loving same-sex relationships to polygamy and bestiality - to see that prejudice remains deep-seated in some disproportionately vocal quarters. Thankfully this polling, conducted by YouGov among over 2,000 adults, clearly shows that these views are increasingly out of touch with modern Britain. The majority of people support what has been done to secure equality for lesbian, gay and bisexual people but they also strongly support going further still. Seven in ten Britons – and, crucially, almost as many Britons of faith – agree with extending the legal form of marriage to same-sex couples. This polling also shows, however, the scale of the challenge we continue to face. Three in five people acknowledge that prejudice still exists against gay people, 2.4 million people have witnessed homophobic bullying at work and two thirds of young people witnessed homophobic bullying in their own school. And they are clear that this should be tackled. We can rightly be proud, as a nation, of the progress we have made. It would have been quite unthinkable at the start of the Queen’s reign that in the year of her Diamond Jubilee more than four in five of her British subjects would feel comfortable if her heir was gay. -

Delga Sept 2007 Newsletter

Delga Brighton 2007 The newsletter of DELGA, Liberal Democrats for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Equality LGBT Equality: Where next? Chair’s Column Welcome back to Brighton! It’s hard to believe it’s been a year already. We had a great AGM last year, full of energy and ambition for the organisation. DELGA has moved forward since then and in particular membership communications have improved, with newsletter mailings in October and November last year, and January, March, June this year and the AGM calling notice in August. We’ve also been contacting newly-selected PPCs to congratulate them, thank them for Our Exec the work they will be doing and remind them DELGA is available to help The 2007 DELGA executive are: with LGBT issues whether they choose to join us or not. Honorary President Evan Harris MP However with a General Election in the air we need to quicken our pace; we need a bigger team for that than that listed to the left, so here’s to Chair a productive AGM. If you have time to spare, and particularly if there is Jen Yockney an area of work which you are skilled in and could commit to over the [email protected] coming year I strongly urge you to stand either for the 2008 exec or to contact them after the AGM to offer assistance: DELGA’s resources both Secretary in cash and people are limited and the load needs to be more widely Eve Friday spread. [email protected] As well as the AGM there will be our joint fringe with Stonewall on the Treasurer way ahead for LGBT equality on Monday night.