Interreligious Dialogues in Switzerland a Multiple-Case Study Focusing on Socio-Political Contexts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canton of Vaud: a Drone Industry Booster

Credit photo: senseFly Canton of Vaud: a drone industry booster “We now Engineering Quality, Trusted Applications & Neutral Services practically cover Switzerland offers a unique multicultural and multidisciplinary drone ecosystem ideally the entire located in the centre of Europe. Swiss drone stakeholders have the expertise and spectrum of experience that can be leveraged by those looking to invest in a high growth industry, technology for develop their own business or hire talent of this new era for aviation. Foreign small drones: companies, like Parrot and GoPro, have already started to invest in Switzerland. sensors and control, Team of teams mechatronics, Swiss academia, government agencies, established companies, startups and industry mechanical associations have a proven track record of collaborating in the field of flying robotics design, and unmanned systems. Case in point: the mapping solution proposed by senseFly communication, (hardware) and Pix4D (software). Both are EPFL spin-offs, respectively from the and human Intelligent Systems Lab & and the Computer Vision Labs. They offer a good example of interaction.” how proximity to universities and the Swiss aviation regulator (FOCA) gave them a competitive and market entry advantage. Within three years the two companies have Prof. Dario Floreano, collectively created 200 jobs in the region and sell their products and services Director, Swiss worldwide. Another EPFL spin-off, Flyability, was able to leverage know-how of National Centre of regionally strong, robust and lightweight structure specialists, Décision and North TPT Competence and to produce their collision tolerant drone that won The UAE Drones for Good Award of Research Robotics USD One Million in 2015. -

Canton of Basel-Stadt

Canton of Basel-Stadt Welcome. VARIED CITY OF THE ARTS Basel’s innumerable historical buildings form a picturesque setting for its vibrant cultural scene, which is surprisingly rich for THRIVING BUSINESS LOCATION CENTRE OF EUROPE, TRINATIONAL such a small canton: around 40 museums, AND COSMOPOLITAN some of them world-renowned, such as the Basel is Switzerland’s most dynamic busi- Fondation Beyeler and the Kunstmuseum ness centre. The city built its success on There is a point in Basel, in the Swiss Rhine Basel, the Theater Basel, where opera, the global achievements of its pharmaceut- Ports, where the borders of Switzerland, drama and ballet are performed, as well as ical and chemical companies. Roche, No- France and Germany meet. Basel works 25 smaller theatres, a musical stage, and vartis, Syngenta, Lonza Group, Clariant and closely together with its neighbours Ger- countless galleries and cinemas. The city others have raised Basel’s profile around many and France in the fields of educa- ranks with the European elite in the field of the world. Thanks to the extensive logis- tion, culture, transport and the environment. fine arts, and hosts the world’s leading con- tics know-how that has been established Residents of Basel enjoy the superb recre- temporary art fair, Art Basel. In addition to over the centuries, a number of leading in- ational opportunities in French Alsace as its prominent classical orchestras and over ternational logistics service providers are well as in Germany’s Black Forest. And the 1000 concerts per year, numerous high- also based here. Basel is a successful ex- trinational EuroAirport Basel-Mulhouse- profile events make Basel a veritable city hibition and congress city, profiting from an Freiburg is a key transport hub, linking the of the arts. -

Clarity on Swiss Taxes 2019

Clarity on Swiss Taxes Playing to natural strengths 4 16 Corporate taxation Individual taxation Clarity on Swiss Taxes EDITORIAL Welcome Switzerland remains competitive on the global tax stage according to KPMG’s “Swiss Tax Report 2019”. This annual study analyzes corporate and individual tax rates in Switzerland and internationally, analyzing data to draw comparisons between locations. After a long and drawn-out reform process, the Swiss Federal Act on Tax Reform and AHV Financing (TRAF) is reaching the final stages of maturity. Some cantons have already responded by adjusting their corporate tax rates, and others are sure to follow in 2019 and 2020. These steps towards lower tax rates confirm that the Swiss cantons are committed to competitive taxation. This will be welcomed by companies as they seek stability amid the turbulence of global protectionist trends, like tariffs, Brexit and digital service tax. It’s not just in Switzerland that tax laws are being revised. The national reforms of recent years are part of a global shift towards international harmonization but also increased legislation. For tax departments, these regulatory developments mean increased pressure. Their challenge is to safeguard compliance, while also managing the risk of double or over-taxation. In our fast-paced world, data-driven technology and digital enablers will play an increasingly important role in achieving these aims. Peter Uebelhart Head of Tax & Legal, KPMG Switzerland Going forward, it’s important that Switzerland continues to play to its natural strengths to remain an attractive business location and global trading partner. That means creating certainty by finalizing the corporate tax reform, building further on its network of FTAs, delivering its “open for business” message and pressing ahead with the Digital Switzerland strategy. -

PARLIAMENT of CANTON VAUD LAUSANNE, SWITZERLAND a BONELL I GIL + ATELIER CUBE ARCHITECTS 1 /4

PARLIAMENT OF CANTON VAUD LAUSANNE, SWITZERLAND A BONELL i GIL + ATELIER CUBE ARCHITECTS 1 /4 Site plan Befor the fire Fire 2002 The Parliament of Lausanne, originally built by Alexandre Perregaux in 1803 rebuilt by Viollet-le-Duc in the 1800s) and the The façade of Rue Cité-Devant, a grand opening that acts as the new on the occasion of the foundation of the Canton of Vaud, was destroyed by Saint-Maire Castle (built in the fourteenth cen- access to the building. Crossing the threshold means entering into a parti- a fire in 2002. tury) provides a setting that rebalances the cular atmosphere, a space that fuses the past and the present. presence of the religious and military institu- Its reconstruction presented the opportunity to reassess the criteria that tions. The reconstruction of the Salle Perregaux, with its neoclassical façade saved would allow to solve both the parliamentary seat and the revitalization of the from the fire, is another of the attractions of the project. The old entrance to neighbouring buildings. In closer view, the project presents itself as a unitary ensemble, formally the Parliament is now used as a Salle des pas perdus, a hall for gatherings. autonomous, containing all part of the programme and where the Great As- The project proposed an architecture capable of restoring the continuity and sembly Hall assumes its prominent role both spatially and functionally. The new Parliament headquarters has been erected on top of historical ves- atmosphere of the historical city. An architecture that would be the synthesis tiges and wants to present itself as an efficient and modern building, cons- between old and new, between traditional construction and new technolo- The three-storey high foyer unites and separates the diverse spaces, but it tructed using innovative techniques but offering an image of timelessness. -

La Broye À Vélo Veloland Broye 5 44

La Broye à vélo Veloland Broye 5 44 Boucle 5 Avenches tel â euch N e Lac d Boucle 4 44 Payerne 5 Boucle 3 44 Estavayer-le-Lac 63 Boucle 2 Moudon 63 44 Bâle e Zurich roy Bienne La B Lucerne Neuchâtel Berne Yverdon Avenches 1 0 les-Bains Payerne Boucle 1 9 Thoune 8 Lausanne 3 Oron 6 6 6 Sion 2 Genève Lugano 0 c Martigny i h p a r g O 2 H Boucle 1 Oron Moudon - Bressonnaz - Vulliens Ferlens - Servion - Vuibroye Châtillens - Oron-la-Ville Oron-le-Châtel - Chapelle Promasens - Rue - Ecublens Villangeaux - Vulliens Bressonnaz - Moudon 1000 800 600 400 m 0,0 5,0 10,0 15,0 20,0 25,0 30,0 35,0 km Boucle 1 Oron Curiosités - Sehenwürdigkeiten Zoo et Tropiquarium 1077 Servion Adultes: CHF 17.- Enfants: CHF 9.- Ouvert tous les jours de 9h à 18h. Tél. 021 903 16 71/021 903 52 28 Fax 021 903 16 72 /021 903 52 29 www.zoo-servion www.tropiquarium.ch [email protected] Le menhir du "Dos à l'Ane" Aux limites communales d'Essertes et Auborange Le plus grand menhir de Suisse visible toute l'année Tél. 021 907 63 32 Fax 021 907 63 40 www.region-oron.ch [email protected] ème Château d'Oron - Forteresse du 12 siècle 1608 Oron-le-Châtel Ouvert d'avril à septembre de 10h à 12h et de 14h à 18h. Groupes de 20 personnes ouvert toute l'année sur rendez-vous. Tél. 021 907 90 51 Fax 021 907 90 65 www.swisscastles.ch [email protected] Hébergement - Unterkünfte (boucle 2 Moudon) Chambre d’hôte Catégorie*** Y. -

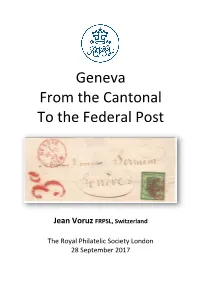

Geneva from the Cantonal to the Federal Post

Geneva From the Cantonal To the Federal Post Jean Voruz FRPSL, Switzerland The Royal Philatelic Society London 28 September 2017 Front cover illustration On 1 st October 1849, the cantonal posts are reorganized and the federal post is created. The Geneva cantonal stamps are still valid, but the rate for local letters is increased from 5 to 7 cents. As the "Large Eagle" with a face value of 5c is sold at the promotional price of 4c, additional 3c is required, materialized here by the old newspapers stamp. One of the two covers being known dated on the First Day of the establishment of the Federal Service. 2 Contents Frames 1 - 2 Cantonal Post Local Mail Frame 2 Cantonal Post Distant Mail Frame 3 Cantonal Post Sardinian & French Mail Frame 4 Transition Period Nearest Cent Frames 4 - 6 Transition Period Other Phases Frame 7 Federal Post Local Mail Frame 8 Federal Post Distant Mail Frames 9 - 10 Federal Post Sardinian & French Mail Background Although I started collecting stamps in 1967 like most of my classmates, I really entered the structured philately in 2005. That year I decided to display a few sheets of Genevan covers at the local philatelic society I joined one year before. Supported by my new friends - especially Henri Grand FRPSL who was one of the very best specialists of Geneva - I went further and got my first FIP Large Gold medal at London 2010 for the postal history collection "Geneva Postal Services". Since then the collection received the FIP Grand Prix International at Philakorea 2014 and the FEPA Grand Prix Finlandia 2017. -

Lump-Sum Taxation Regime for Individuals in Switzerland by End of 2014, Swiss Voters Decided by a Clear Majority to Maintain the Lump-Sum Taxation Regime

Lump-Sum Taxation Regime for Individuals in Switzerland By end of 2014, Swiss voters decided by a clear majority to maintain the lump-sum taxation regime. At federal level the requirements to qualify for being taxed under the lump-sum regime will be slightly amended. Cantonal regulations also consider adjustments to ensure an attractive and pragmatic lump-sum taxation regime for selected individual tax payers. Background is then subject to ordinary tax rates the Lump-sum taxation are Schwyz, Under the lump-sum tax regime, applicable at the place of residence. As Zug, Vaud, Grisons, Lucerne and Valais. foreign nationals taking residence a consequence, it is not necessary to In autumn 2012, more stringent rules in Switzerland who do not engage in report effective earnings and wealth. to tighten the lump-sum taxation were gainful employment in Switzerland may The lump-sum taxation regime may be approved by the Swiss parliament to choose to pay an expense-based tax attractive to wealthy foreigners given strengthen its acceptance. The revised instead of ordinary income and wealth the fact that the ordinary tax rates only legislation will be effective on federal tax. Typically, the annual living expenses apply to a portion of the taxpayer’s and cantonal level as of 1 January 2016. of the tax payer and his family, which worldwide income and assets. are considered to be the tax base, are Current legislation and rulings in disclosed and agreed on in a ruling Over the last years this taxation regime place continue to be applicable for a signed and confirmed by the competent has come under some pressure in transitional period of five years from cantonal tax authority prior to relocating Switzerland. -

Local and Regional Democracy in Switzerland

33 SESSION Report CG33(2017)14final 20 October 2017 Local and regional democracy in Switzerland Monitoring Committee Rapporteurs:1 Marc COOLS, Belgium (L, ILDG) Dorin CHIRTOACA, Republic of Moldova (R, EPP/CCE) Recommendation 407 (2017) .................................................................................................................2 Explanatory memorandum .....................................................................................................................5 Summary This particularly positive report is based on the second monitoring visit to Switzerland since the country ratified the European Charter of Local Self-Government in 2005. It shows that municipal self- government is particularly deeply rooted in Switzerland. All municipalities possess a wide range of powers and responsibilities and substantial rights of self-government. The financial situation of Swiss municipalities appears generally healthy, with a relatively low debt ratio. Direct-democracy procedures are highly developed at all levels of governance. Furthermore, the rapporteurs very much welcome the Swiss parliament’s decision to authorise the ratification of the Additional Protocol to the European Charter of Local Self-Government on the right to participate in the affairs of a local authority. The report draws attention to the need for improved direct involvement of municipalities, especially the large cities, in decision-making procedures and with regard to the question of the sustainability of resources in connection with the needs of municipalities to enable them to discharge their growing responsibilities. Finally, it highlights the importance of determining, through legislation, a framework and arrangements regarding financing for the city of Bern, taking due account of its specific situation. The Congress encourages the authorities to guarantee that the administrative bodies belonging to intermunicipal structures are made up of a minimum percentage of directly elected representatives so as to safeguard their democratic nature. -

WOMEN SEEKING FACULTY POSITIONS in Urban and Regional

2015 FWIG CV Book WOMEN SEEKING FACULTY POSITIONS in Urban and Regional Planning Prepared by the Faculty Women’s Interest Group (FWIG) The Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning October 2015 Dear Department Chairs, Heads, Directors, and Colleagues: The Faculty Women’s Interest Group (FWIG) of the Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning (ACSP) is proud to present you with the 2014 edition of a collection of abbreviated CVs of women seeking tenure-earning faculty positions in Urban and Regional Planning. Most of the women appearing in this booklet are new PhD’s or just entering the profession, although some are employed but looking for new positions. Most are seeking tenure-track jobs, although some may consider a one-year, visiting, or non-tenure earning position. These candidates were required to condense their considerable skills, talents, and experience into just two pages. We also forced the candidates to identify their two major areas of interest, expertise, and/or experience, using our categories. The candidates may well have preferred different categories. Please carefully read the brief resumes to see if the candidates meet your needs. We urge you to contact the candidates directly for additional information on what they have to offer your program. On behalf of FWIG we thank you for considering these newest members of our profession. If we can be of any help, please do not hesitate to call on either of us. Sincerely !Dr. J. Rosie Tighe Dr. K. Meghan Wieters Editor, 2014 Resume Book President, FWIG! [email protected] -

Naturalisation » Questions Locales Corcelles-Le-Jorat

Questionnaire « naturalisation » Questions locales Corcelles-le-Jorat GEOGRAPHIE QUESTION 1 Qui est propriétaire de l’auberge communale ? ☐ L’Association des Amis de l’Auberge ☐ Le comité de l’ancien chœur mixte Sàrl ☒ La Commune ☐ Le restaurateur QUESTION 2 Quelle est l’entreprise de transports en commun traversant le village ? ☐ Les Bus du Jorat, ligne 1 ☒ Car Postal, ligne 383 ☐ L’Entreprise PP (Porchet-Pullman) ☐ Les Transports Lausannois, ligne 22 QUESTION 3 Quel est le nom des habitants de Corcelles-le-Jorat ? ☐ Les Corsellinnois / Corsellinnoises ou les Belles descentes ☐ Les Coqs hardis / Coquettes hardies ou les Fiereaux chapuns ☐ Les Coqelards / Coqelardes ou les Gaux fumats ☒ Les Corçallins / Corçalinnes ou les Grands cous QUESTION 4 Quel est le nombre moyen d’habitants à Corcelles-le-Jorat ? ☐ Entre 260 et 300 habitants ☐ Entre 340 et 380 habitants ☒ Entre 410 et 470 habitants ☐ Entre 500 et 540 habitants QUESTION 5 Quel est le point le plus haut en altitude de la commune ? ☐ En Gillette ☐ La Moille-aux-Blanc ☒ Le Bois Vuacoz ☐ Le Moulin QUESTION 6 De quelle vallée les deux ruisseaux de Corcelles sont-ils affluents ? ☒ La Broye ☐ L’Eau Tzaudet ☐ Le Rhône ☐ La Venoge QUESTION 7 Quelle superficie du territoire de la commune est-il couvert par des forêts ? ☐ 794 hectares, soit 100% ☐ 660 hectares, soit 20% ☐ 365 hectares, soit 12% ☒ 300 hectares, soit 40% QUESTION 8 Quels sont les bâtiments communs regroupés au centre du village ? ☒ Auberge, église, grande salle ☐ Bureau de poste, école, épicerie ☐ Caserne, école, église ☐ Château, -

Regional Inequality in Switzerland, 1860 to 2008

Economic History Working Papers No: 250/2016 Multiple Core Regions: Regional Inequality in Switzerland, 1860 to 2008 Christian Stohr London School of Economics Economic History Department, London School of Economics and Political Science, Houghton Street, London, WC2A 2AE, London, UK. T: +44 (0) 20 7955 7084. F: +44 (0) 20 7955 7730 LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC HISTORY WORKING PAPERS NO. 250 - SEPTEMBER 2016 Multiple Core Regions: Regional Inequality in Switzerland, 1860 to 2008 Christian Stohr London School of Economics Abstract This paper estimates regional GDP for three different geographical levels in Switzerland. My analysis of regional inequality rests on a heuristic model featuring an initial growth impulse in one or several core regions and subsequent diffusion. As a consequence of the existence of multiple core regions Swiss regional inequality has been comparatively low at higher geographical levels. Spatial diffusion of economic growth has occurred across different parts of the country and within different labor market regions at the same time. This resulted in a bell- shape evolution of regional inequality at the micro regional level and convergence at higher geographical levels. In early and in late stages of the development process, productivity differentials were the main drivers of inequality, whereas economic structure was determinant between 1888 and 1941. Keywords: Regional data, inequality, industrial structure, productivity, comparative advantage, switzerland JEL Codes: R10, R11, N93, N94, O14, O18 Acknowledgements: I thank Heiner Ritzmann-Blickensdorfer and Thomas David for sharing their data on value added by industry with me. I’m grateful to Joan Rosés, Max Schulze, and Ulrich Woitekfor several enlightening discussions. -

On the Way to Becoming a Federal State (1815-1848)

Federal Department of Foreign Affairs FDFA General Secretariat GS-FDFA Presence Switzerland On the way to becoming a federal state (1815-1848) In 1815, after their victory over Napoleon, the European powers wanted to partially restore pre-revolutionary conditions. This occurred in Switzerland with the Federal Pact of 1815, which gave the cantons almost full autonomy. The system of ruling cantons and subjects, however, remained abolished. The liberals instituted a series of constitutional reforms to alter these conditions: in the most important cantons in 1830 and subsequently at federal level in 1848. However, the advent of the federal state was preceded by a phase of bitter disputes, coups and Switzerland’s last civil war, the Sonderbund War, in 1847. The Congress of Vienna and the Restoration (1814–1830) At the Congress of Vienna in 1814 and the Treaty of Paris in 1815, the major European powers redefined Europe, and in doing so they were guided by the idea of restoration. They assured Switzerland permanent neutrality and guaranteed that the completeness and inviolability of the extended Swiss territory would be preserved. Caricature from the year 1815: pilgrimage to the Diet in Zurich. Bern (the bear) would like to see its subjects Vaud and Aargau (the monkeys) returned. A man in a Zurich uniform is pointing the way and a Cossack is driving the bear on. © Historical Museum Bern The term “restoration”, after which the entire age was named, came from the Bernese patrician Karl Ludwig von Haller, who laid the ideological foundations for this period in his book “Restoration of the Science of the State” (1816).