Brick and Click Libraries: the Shape of Tomorrow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISSUE 4 ® the Newsletter Designed for Nexis.Com Power Users FOURTH QUARTER

LexisNexis® Corporate Information Professional Update ISSUE 4 ® The newsletter designed for nexis.com power users FOURTH QUARTER What’s new at nexis.com®, plus searching strategies to help “power users” solve the information issues their businesses face. Full-text features: New biographical group sources on executives trim The new current-awareness tool developed your research time and compile results specifically for small to midsize organizations … LexisNexis now offers four new group sources at nexis.com® and lexis.com® LexisNexis® Publisher … 12:62 that provide detailed biographical information on company executives, New biographical group sources on executives employees and government leaders. trim your research time and compile results … 12:65 One search covers 20+ executive biographical sources The Executive Directories provides biographical information on directors and executives of major corporations in the United States and Europe. Search by executive name, company, city/state or a variety of other sections. Find summaries and/or links to full-text PDFs of: Review the sources available through The Executive Directories. One million phone numbers added to Search results are presented in standard nexis.com group source format, LexisNexis® Public Records sources … 12:56 with a left navigation pane that allows you to focus in on specific publications within the results. Trademark prosecution history now included with registration documents … 12:56 Get people news plus biographical stories in one source Biographies Plus News adds people-related news sources and selected ® LexisNexis Company Dossier: Search by biographical stories, obituaries and business-related stories covering ® radius or Fortune designation … 12:56 company executives from the News, All (English, Full Text) source. -

Business Source Main Edition Magazines and Journals

Business Source Main Edition Magazines and Journals 2213 = Total number of journals & magazines indexed and abstracted (787 are peer-reviewed ) 665 = Total number of journals & magazines in full text (221 are peer-reviewed ) *Titles with 'Coming Soon' in the Availability column indicate that this publication was recently added to the database and therefore few or no articles are currently available. If the ‡ symbol is present, it indicates that 10% or more of the articles from this publication may not contain full text because the publisher is not the rights holder. Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. The numbers given at the top of this list reflect all titles, active and ceased. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Information Services is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Source Type ISSN Publication Name Publisher Indexing and Indexing and Full Text Start Full Text Stop Full Text Peer- PDF Image Country Availability* MID Abstracting Start Abstracting Stop Delay Review Images QuickVie (Months) ed (full w page) Trade Publication 0192- 20/20 Jobson Healthcare Information LLC 11/01/2006 United States of Available Now 1G2E 1304 America Trade Publication 0149- 33 Metalproducing Penton Publishing 07/01/1999 12/31/2002 -

Список Источников Для Продукта Lexisnexis Academic

Список источников для продукта LexisNexis Academic LN Academic Source Package (EUROPE) (Menu ZZYXZ1 - 11 846 ) Оглавление News-5980 Sources .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Aggregate News Sources-119 Sources............................................................................................................. 4 Industry Trade Press-1260 Sources .................................................................................................................. 5 Newspapers-2062 Sources.............................................................................................................................. 16 Blogs-38 Sources............................................................................................................................................ 35 Web-based Publications-230 Sources............................................................................................................. 35 Magazines & Journals-1589 Sources.............................................................................................................. 37 Newsletters-964 Sources ................................................................................................................................ 51 Newswires & Press Releases-703 Sources ..................................................................................................... 59 News Transcripts-85 Sources ........................................................................................................................ -

Annual Report 2018 / 2018 Report Annual Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 / ANNUAL REPORT / NEW MEDIA INVESTMENT GROUP INC. 2018 NEW MEDIA OVERVIEW 5+ MILLION New Media A leading source of local SMALL & MEDIUM BUSINESSES IN OUR MARKETS news and premier SMB solutions provider for its small to mid-sized communities PAID PRINT 1.6M CIRCULATION OPERATE IN 580+ REACH OVER 22 MARKETS ACROSS MILLION PEOPLE 600+ 146 37 STATES ON A WEEKLY BASIS TOTAL COMMUNITY DAILY PUBLICATIONS NEWSPAPERS SMB SOLUTIONS PROVIDER SERVES 199K+ SMALL & MEDIUM 54M+ VISITORS BUSINESSES & PAGE 365M VIEWS 1,160+ IN-MARKET SALES PAID DIGITAL REPRESENTATIVES All figures are as of December 30, 2018 145K CIRCULATION COMMUNITY FOCUSED SOLUTIONS COMMUNITY FOCUSED SUCCESSFUL EXECUTION OF NEW MEDIA INVESTMENT GROUP // 01 OUR STRATEGY Diversify revenue Diversified away from Traditional Print revenue, which was base to create 56% of total revenue in FY 2013 to now only 41% of total organic revenue and revenue in FY 2018(1) cash flow growth UpCurve revenue was $95.8 million for FY 2018, a 72% Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) since FY 2013 GateHouse Live and Promotions combined revenue of $45.7 million in FY 2018, in increase of 58% to the prior year 01. ORGANIC GROWTH 02. ACQUISITIONS Out of favor and Completed Purchase price Average unlevered fragmented industry $1.1 billion in has averaged 4.1x yield of 23%(4) and has created attrac- acquisitions the Seller’s LTM average levered tive pricing for assets since spin-out(2) As Adjusted yield of 28%(5) EBITDA(3) Return a meaningful portion of free cash flow to shareholders $6.46 $6.08 2018 dividends of $1.49 per common share $5.70 $0.38 $5.33 $0.38 $4.96 $0.37 $4.59 $0.37 $4.22 $0.37 $3.87 $0.37 $3.52 $0.35 $3.17 $0.35 $2.82 $0.35 $2.49 $0.35 $2.16 $0.33 $1.83 $0.33 $1.50 $0.33 $1.17 $0.33 $0.84 $0.33 $0.54 $0.33 $0.27 $0.30 $0.27 $0.27 Q2 Q3 Q3 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 03. -

(The) Last Magazine 2 1 40.32 5/7/2015 46014 032C

SKU Product Issues Years Price Updated 44233 (t)here 2 3 30.00 5/7/2015 46003 (The) Last Magazine 2 1 40.32 5/7/2015 46014 032c 2 1 101.96 5/7/2015 45532 10 Magazine 2 1 48.50 5/7/2015 45533 10 Men 2 1 45.00 5/7/2015 51333 1602 Witch Hunter 12 1 29.99 7/30/2015 45534 18 Karati Export 2 1 65.50 5/7/2015 45535 18 Karati Gold & Fashion 6 1 157.50 5/7/2015 46354 25 Beautiful Homes 12 1 163.45 5/7/2015 48210 25Ans 12 1 261.67 5/7/2015 44316 30+ MILF Combo (no DVD) 6 2 35.00 11/29/2016 44317 40+ Magazine (no DVD) 6 2 35.00 11/29/2016 51452 417 Magazine 12 2 27.00 12/12/2017 45179 4TH D Wellbeing 12 1 60.00 5/7/2015 44319 50+ Magazine (no DVD) 6 2 35.00 11/29/2016 46357 A Tavola 12 1 215.16 5/7/2015 48148 A+U 12 1 682.04 5/7/2015 40528 ABC Soaps in Depth 26 1 39.97 9/6/2017 44401 Ability 12 1 29.70 5/7/2015 45761 Abitare 12 1 368.97 5/7/2015 46017 Acclaim 4 1 80.64 5/7/2015 3158 Acoustic Guitar 12 3 40.00 4/5/2018 63158 Acoustic Guitar - Digital 12 3 40.00 4/5/2018 1108 Action Comics (1/2 year) 12 1 24.99 10/12/2016 4446 ADDitude 4 1 19.95 1/11/2018 60047 Adoption Today - Digital 12 1 12.00 5/7/2015 48361 Adventist Review 12 1 36.95 11/2/2015 1653 Adweek 45 1 99.00 5/7/2015 61653 Adweek - Digital 45 1 99.00 5/7/2015 46360 Aeroplane Monthly 12 1 157.06 5/7/2015 45834 Aesthetica 6 1 88.25 5/7/2015 45222 AFAR 6 2 20.00 5/7/2015 45334 Affordable Housing Finance 6 1 119.00 5/7/2015 51334 A-Force 12 1 29.99 7/30/2015 42696 African American Golfers Digest 4 1 18.00 5/7/2015 46364 Afrique Asie 12 1 124.42 5/7/2015 46365 Afrique Magazine 12 1 162.93 5/7/2015 -

Business & Company Resource Center

Business & Company Resource Center Business & Company Resource Center brings together in a single database company profiles, company brand information, rankings, investment reports, company histories, chronologies, and periodicals. Search this database to find detailed company and industry news and information. This title list provides detailed information on the periodicals covered in this database. Updated November 1, 2009 Journal Name ISSN Index Start Index End Full-text Full-text Image Image End Format Refereed/Peer- Embargo Publisher Name Publisher Country Start End Start Reviewed (Days) 123Jump 4/2001 1/2002 4/2001 1/2002 Newswire COMTEX News Network, Inc. United States 2.5G-3G 1540-0719 2/2002 4/2006 Newsletter Information Gatekeepers, Inc. United States --- Now: 2.5G-4G. Effective Date = 12/01/2007; Former: Wireless Cellular. Effective Date = 01/30/2002 2008 Survey of Small and Mid-Sized Business 1/2008 1/2008 1/2008 Report National Small Business Association United States 2008 Year End Economic Report 1/2008 1/2008 1/2008 Report National Small Business Association United States 2009 Energy Survey of Small Business 1/2009 1/2009 1/2009 Report National Small Business Association United States 2009 Health Care Survey of Small Business 1/2009 1/2009 1/2009 Report National Small Business Association United States 2009 Small Business Credit Card Survey 1/2009 1/2009 1/2009 Report National Small Business Association United States 33 Metalproducing 0149-1210 11/2000 11/2002 11/2000 11/2002 12/2000 11/2002 Magazine/Journal Penton Media, Inc. United States --- Now: Metal Producing & Processing. Effective Date = 12/31/2002 3G Mobile 10/2002 11/2003 10/2002 11/2003 Newsletter Informa UK Ltd. -

ISSUE 4 the Newsletter Designed for Nexis.Com® Power Users FOURTH QUARTER

® LexisNexis Corporate Information Professional Update ISSUE 4 The newsletter designed for nexis.com® power users FOURTH QUARTER What’s new from the LexisNexis® services? by Nancy Gallenson, Manager, LexisNexis Business Insights Solutions Titles listed below are organized by geographic coverage then alphabetically by title. All titles are linked to their entry in the Searchable Directory of Online Sources. Click to learn more about each title. Go to http://www.lexisnexis.com/newsandbusiness/ content/ for the entire archive of news and business content additions back to 2005. Highlights Food & Drink Digital covers industry-specific issues such as: drinks, food equipment, food manufacturing, health foods This update includes the return of Frankfurter Allgemeine and drinks, ingredients, hotels, restaurants and more. Zeitung, the preeminent German language newspaper, to the LexisNexis® services. Also noteworthy is NetProspex, a Healthcare Digital covers solutions that enable global contacts database for B2B professionals. We have added 17 healthcare executives to improve the way they manage their White Digital Media publications which deliver digital news operations. It provides information on industry-specific issues and information for business professionals and global reviews such as: finance & insurance; health service; hospitals; medical for operations, technology, finance and leadership. A focus on devices; and pharmaceuticals. Asia brings new English-language titles published in a variety of International Journal of Energy Sector Management facilitates countries including Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, India, Pakistan, Nepal, the dissemination of research on issues relating to supply Bahrain, and Bangladesh. And for the Middle East, we have added management (covering the entire supply chain of resource 49 Arabic-language publications to the LexisNexis services. -

Florida Chapter Shines at Kips Bay Show House Supported by EF

A QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL FURNISHINGS AND DESIGN ASSOCIATION INTERNATIONAL PLATINUM SPONSORS INTERNATIONAL IN THIS GOLD SPONSOR ISSUE ■ Florida Chapter Shines at Kips Bay Show House ■ Supported By EF Grant, Creator Of IFDA Selects Launches New Phase Of Her Own Career ■ Chapter News BOARD OF DIRECTORS President Ida McCausland [email protected] Immediate Past President Janet Stevenson, FIFDA [email protected] Treasurer Dave Gilbert, FIFDA [email protected] Directors IFDA Selects Best of Show Award Winners Judith Clark Janofsky, FIFDA [email protected] THE INTERNATIONAL FURNISHINGS AND DESIGN ASSOCIATION MAGAZINE Rose Gilbert, FIFDA [email protected] Contents Spring 2019 Chris Magliozzi Editor: Rose Gilbert, FIFDA [email protected] Educational Foundation Chair CONTENTS Merry Mabbett Dean, FIFDA President’s Message ................................................................................................... 1 [email protected] Florida Chapter Shines at Kips Bay Show House ........................................................ 2 Account Manager IFDA Selects: Best of Show Awards ........................................................................... 4 Linda Kulla, FIFDA CHAPTER NEWS [email protected] Arizona Chapter.......................................................................................................... 4 Florida Chapter ........................................................................................................... 5 COUNCIL OF PRESIDENTS Illinois -

Document Title

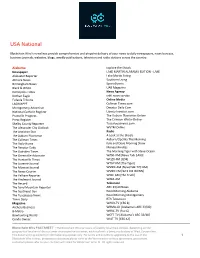

USA National Blockchain Wire’s newslines provide comprehensive and pinpoint delivery of your news to daily newspapers, news bureaus, business journals, websites, blogs, weekly publications, television and radio stations across the country. Alabama Explore the Shoals Newspaper LAKE MARTIN ALABAMA EDITION - LAKE Alabaster Reporter Lake Martin Living Atmore News Southern Living Birmingham News SportsEvents Black & White UAB Magazine Demopolis Times News Agency Dothan Eagle cnhi news service Eufaula Tribune Online Media LAGNIAPPE Cullman Times.com Montgomery Advertiser Decatur Daily.Com National Catholic Register Liberty Investor.com Prattville Progress The Auburn Plainsman Online Press-Register The Crimson White-Online Shelby County Reporter Tuscaloosanews.com The Alexander City Outlook WVTM Online The Anniston Star Radio The Auburn Plainsman A Look at the Shoals The Cullman Times Auburn/Opelika This Morning The Daily Home Kyle and Dave Morning Show The Decatur Daily Money Minutes The Gadsden Times The Morning Tiger with Steve Ocean The Greenville Advocate WANI-AM [News Talk 1400] The Huntsville Times WQZX-FM [Q94] The Luverne Journal WTGZ-FM [The Tiger] The Monroe Journal WVNN-AM [NewsTalk 770 AM] The News-Courier WVNN-FM [92.5 FM WVNN] The Pelham Reporter WXJC-AM [The Truth] The Piedmont Journal WZZA-AM The Record Television The Sand Mountain Reporter ABC 33/40 News The Southeast Sun Good Morning Alabama The Tuscaloosa News Good Morning Montgomery Times Daily RTA Television Magazine WAKA-TV [CBS 8] Archery Business WBMA-LD [Alabama's ABC 33/40] B-Metro WBRC-TV [Fox 6] Bowhunting World WCFT-TV [Alabama's ABC 33/40] Condo Owner WIAT-TV [CBS 42] Blockchain Wire FACTSHEET | The Blockchain Wire service is offered by local West entities, depending on the geographical location of the customer or prospective customer, each such entity being a subsidiary of West Corporation. -

Mainfile Magazines and Journals

MainFile Magazines and Journals 5645 = Total number of journals & magazines indexed and abstracted (3440 are peer-reviewed ) 5252 = Total number of journals & magazines in full text (3200 are peer-reviewed ) *Titles with 'Coming Soon' in the Availability column indicate that this publication was recently added to the database and therefore few or no articles are currently available. If the ‡ symbol is present, it indicates that 10% or more of the articles from this publication may not contain full text because the publisher is not the rights holder. Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. The numbers given at the top of this list reflect all titles, active and ceased. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Information Services is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Source Type ISSN Publication Name Publisher Indexing and Indexing and Full Text Start Full Text Stop Full Text Peer- PDF Image Country Availability* MID Abstracting Start Abstracting Stop Delay Review Images QuickVie (Months) ed (full w page) Trade Publication 0192- 20/20 Jobson Healthcare Information LLC 11/01/2006 11/01/2006 Y United States of Available Now 1G2E 1304 America Trade Publication 0149- 33 Metalproducing Penton Publishing 07/01/1999 12/31/2002 07/01/1999 -

End-Market Study for Indonesian Home Accessories

END-MARKET STUDY FOR INDONESIAN HOME ACCESSORIES DECEMBER 2007 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Ted Barber of DAI with technical supervision and inputs from Marina Krivoshlykova of DAI. END-MARKET STUDY FOR INDONESIAN HOME ACCESSORIES The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS PREFACE...........................................................................................IX ACRONYMS.......................................................................................XI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................XIII I. INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................1 SENADA AND TARGET ENTERPRISES .......................................1 OBJECTIVE OF END MARKET STUDY ..........................................1 II. THE GLOBAL MARKET FOR INDONESIAN HOME ACCESSORIES ...............................................2 DEFINITION OF HOME ACCESSORIES AND CHALLENGES ASSOCIATED WITH DATA COLLECTION .......................................2 GLOBAL MARKET FOR HOME ACCESSORIES AND MARKET SEGMENTS ..................................................................3 KEY PLAYERS AND DISTRIBUTION CHANNELS ............................7 KEY TRENDS IN DISTRIBUTION CHANNELS ...............................12 PRICE SEGMENTS AND KEY TRENDS ........................................13 -

Before the Public Service Commission of South Carolina

BEFORE THE PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION OF SOUTH CAROLINA Docket No. 2008-327-C EXHIBIT AA-2 TO DIRECT TESTIMONY OF AUGUST H. ANKUM, PH. D. ON BEHALF OF TIME WARNER CABLE INFORMATION SERVICES (SOUTH CAROLINA) LLC FTC Page 1 of 1 Customer Support Locations Employment Contact Us Sitemap The Great Connection Serulues 92TSSPH FTC Weuther Newsletter Cufruht Prulnonohc OITouch LocalSerwces Home > About Us Long Distance Wllslsss About Us Susrness Solugons Farmers Telephone Cooperative, Inc. Internet (FTC), founded in 1951, is a local, multi- + faceted telecommunications company ~t."" ~' headquartered in Kingstree, SC. Serving x over 60,000 customers within a coverage area of 3000 miles, we provide cutting- teem5%IJ@ttttt edge technology to businesses and Online Account Management residents in Williamsburg, Lee, Sumter, Clarendon and Florence counties. A Online Directory veteran in the telephone industry, FTC is the 3rd largest telephone cooperative in E-Page the United States. From a humble beginning utilizing a crank type E Mail switchboard to serve 52 homes, FTC has evolved into a state-of-the-art organization offering local, long distance, paging, digital wireless, Internet access, and DSL services. Customers can choose from our wide array of products and services at any of our seven conveniently located full-service business offices. Two affiliate corporations fall under FTC's umbrella; namely, FTC Communications, Inc. (with two divisions, Farmers Long Distance and FTC Wireless), and FTC Diversified Services, Inc. Services, capabilities and products are explained in detail on other pages of this site. About Us FTC Weather Newsletter Customer Support Employment Contact Us Sitemap © Farmers Telephone Cooperative.