Conservation Implications for the Himalayan Wolf Canis (Lupus) Himalayensis Based on Observations of Packs and Home Sites in Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(DREF) Nepal: Earthquake

Disaster relief emergency fund (DREF) Nepal: Earthquake DREF operation n° MDRNP005 GLIDE n° EQ-2011-000136-NPL 21 September 2011 The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC) Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross and Red Crescent emergency response. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of National Societies to respond to disasters. CHF 172,417 has been allocated from the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies’ (IFRC) Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the National Society in conducting rapid assessments and in delivering immediate assistance to some 1,500 families. Unearmarked funds to repay DREF are encouraged. Summary: On the evening of 18 September, Nepal was shaken by an earthquake measuring 6.9 on the Richter scale. The epicentre is known to be on the Nepal-India border of Taplejung district of Nepal and Sikkim state of India, with a depth of 19.7 km. Tremors were felt throughout Nepal, Bhutan, and some parts of India and Bangladesh. The full extent of the damage is unclear at this stage as many areas remain inaccessible, due to their remote location as well as heavy rainfall and several landslides. The Government of Nepal does not anticipate a need for external assistance but has activated its National Emergency Operations Centre which has identified seven highly affected districts outside of Kathmandu, mainly in the areas close to the earthquake's epicentre. -

ZSL National Red List of Nepal's Birds Volume 5

The Status of Nepal's Birds: The National Red List Series Volume 5 Published by: The Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK Copyright: ©Zoological Society of London and Contributors 2016. All Rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-900881-75-6 Citation: Inskipp C., Baral H. S., Phuyal S., Bhatt T. R., Khatiwada M., Inskipp, T, Khatiwada A., Gurung S., Singh P. B., Murray L., Poudyal L. and Amin R. (2016) The status of Nepal's Birds: The national red list series. Zoological Society of London, UK. Keywords: Nepal, biodiversity, threatened species, conservation, birds, Red List. Front Cover Back Cover Otus bakkamoena Aceros nipalensis A pair of Collared Scops Owls; owls are A pair of Rufous-necked Hornbills; species highly threatened especially by persecution Hodgson first described for science Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson and sadly now extinct in Nepal. Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of any participating organizations. Notes on front and back cover design: The watercolours reproduced on the covers and within this book are taken from the notebooks of Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894). -

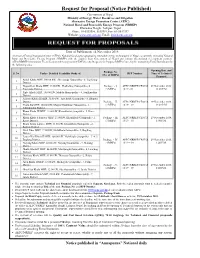

Request for Proposal (Notice Published)

Request for Proposal (Notice Published) Government of Nepal Ministry of Energy, Water Resources and Irrigation Alternative Energy Promotion Centre (AEPC) National Rural and Renewable Energy Program (NRREP) Khumaltar Height, Lalitpur, Nepal Phone: 01-5539390, 5539391, Fax: 01-5542397 Website: www.aepc.gov.np, Email: [email protected] Date of Publication: 14 November 2018 Alternative Energy Promotion Centre (AEPC): National focal agency promoting renewable energy technologies in Nepal, is currently executing National Rural and Renewable Energy Program (NRREP) with the support from Government of Nepal and various international development partners. AEPC/NRREP/Community Electrification Sub-Component (CESC) hereby Requests for Proposal (RFP) from eligible Consulting Firms/Institutions for the following tasks: Opening Date and Package No. S. No. Tasks - Detailed Feasibility Study of: RFP Number Time of Technical (No. of MHPs) Proposal Aamji Khola MHP, 100.00 kW, Shreejanga Gaunpalika - 8, Taplejung 1 District Nagpokhari Khola MHP, 15.00 kW, Phaktalung Gaunpalika - 6, Package - I, AEPC/NRREP/CESC/20 29 November 2018, 2 Taplejung District (3 MHPs) 18/19 - 01 12.20 P.M. Piple Khola MHP, 100.00 kW, Makalu Municipality - 4, Sankhusabha 3 District Aakuwa Khola II MHP, 32.00 kW, Amchowk Gaunpalika - 8, Bhojpur 4 District Package - II, AEPC/NRREP/CESC/20 29 November 2018, Cholu Ku MHP, 100.00 kW, Mapya Dhudhkosi Gaunpalika - 1, (2 MHPs) 18/19 – 02 12:40 P.M. 5 Solukhumbu District Khani Khola III MHP, 11.00 kW, Khanikhola Gaunpalika - 5, Kavre 6 District Khani Khola Falametar MHP, 23.00 kW, Khanikhola Gaunpalika - 2, Package - III, AEPC/NRREP/CESC/20 29 November 2018, 7 Kavre District (3 MHPs) 18/19 – 03 1:00 P.M. -

Table 4-5: Caste/ Ethnic Composition of the Project Districts

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Social Assessment (SA) of Public Disclosure Authorized Kabeli-A Hydroelectric Project MAY 2011 Submitted to WORLD BANK Submitted by KABELI ENERGY LIMITED Buddha Nagar, Kathmandu, Nepal Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by HYDRO CONSULT PRIVATE LIMITED Buddha Nagar, Kathmandu, Nepal HCPL SA of KAHEP Table of contents Page No. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................... 1 1 INTRODUCTION OF THE PROJECT ............................................ 2 1.1 Background context of the KAHEP ...................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Project proponent ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Organization responsible for preparing the report ........................................................................... 4 1.4 Objectives of SA study ............................................................................................................................. 5 2 DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT ................................................ 7 2.1 Project location .......................................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Accessibility ................................................................................................................................................. 7 2.2.1 Overall -

Table of Province 01, Preliminary Results, Nepal Economic Census 2018

Number of Number of Persons Engaged District and Local Unit establishments Total Male Female Taplejung District 4,653 13,225 7,337 5,888 10101PHAKTANLUNG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 539 1,178 672 506 10102MIKWAKHOLA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 269 639 419 220 10103MERINGDEN RURAL MUNICIPALITY 397 1,125 623 502 10104MAIWAKHOLA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 310 990 564 426 10105AATHARAI TRIBENI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 433 1,770 837 933 10106PHUNGLING MUNICIPALITY 1,606 4,832 3,033 1,799 10107PATHIBHARA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 398 1,067 475 592 10108SIRIJANGA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 452 1,064 378 686 10109SIDINGBA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 249 560 336 224 Sankhuwasabha District 6,037 18,913 9,996 8,917 10201BHOTKHOLA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 294 989 541 448 10202MAKALU RURAL MUNICIPALITY 437 1,317 666 651 10203SILICHONG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 401 1,255 567 688 10204CHICHILA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 199 586 292 294 10205SABHAPOKHARI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 220 751 417 334 10206KHANDABARI MUNICIPALITY 1,913 6,024 3,281 2,743 10207PANCHAKHAPAN MUNICIPALITY 590 1,732 970 762 10208CHAINAPUR MUNICIPALITY 1,034 3,204 1,742 1,462 10209MADI MUNICIPALITY 421 1,354 596 758 10210DHARMADEVI MUNICIPALITY 528 1,701 924 777 Solukhumbu District 3,506 10,073 5,175 4,898 10301 KHUMBU PASANGLHAMU RURAL MUNICIPALITY 702 1,906 904 1,002 10302MAHAKULUNG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 369 985 464 521 10303SOTANG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 265 787 421 366 10304DHUDHAKOSHI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 263 802 416 386 10305 THULUNG DHUDHA KOSHI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 456 1,286 652 634 10306NECHA SALYAN RURAL MUNICIPALITY 353 1,054 509 545 10307SOLU DHUDHAKUNDA MUNICIPALITY -

OCHA Nepal Situation Overview

F OCHA Nepal Situation Overview Issue No. 19, covering the period 09 November -31 December 2007 Kathmandu, 31 December 2007 Highlights: • Consultations between the Seven Party Alliance (SPA) breaks political deadlock • Terai based Legislators pull out of government, Parliament • Political re-alignment in Terai underway • Security concerns in the Terai persist with new reports of extortion, threats and abductions • CPN-Maoist steps up extortion drive countrywide • The second phase of registration of CPN-Maoist combatants completed • Resignations by VDC Secretaries continue to affect the ‘reach of state’ • Humanitarian and Development actors continue to face access challenges • Displacements reported in Eastern Nepal • IASC 2008 Appeal completed CONTEXT Constituent Assembly. Consensus also started to emerge on the issue of electoral system to be used during the CA election. Politics and Major Developments On 19 November, the winter session of Interim parliament met Consultations were finalized on 23 December when the Seven but adjourned to 29 November to give time for more Party Alliance signed a 23-point agreement. The agreement negotiations and consensus on constitutional and political provided for the declaration of a republic subject to issues. implementation by the first meeting of the Constituent Assembly, a mixed electoral system with 60% of the members Citing failure of the government to address issues affecting of the CA to be elected through proportional system and 40% their community, four members of parliament from the through first-past-the-post system, and an increase in number Madhesi Community, including a cabinet minister affiliated of seats in the Constituent Assembly (CA) from the current 497 with different political parties resigned from their positions. -

An Overview of the Status and Conservation Initiatives of Red Panda Ailurus Fulgens (Cuvier, 1825) in Nepal

The Initiation An Overview of the Status and Conservation Initiatives of Red Panda Ailurus fulgens (Cuvier, 1825) in Nepal Damber Bista1 and Rajiv Paudel2 Corresponding author: Damber Bista Email: [email protected] Abstract The existing status of Red Panda Ailurus fulgens in Nepal is poorly known. Current work attempts to put the information on Red Panda status together from Nepal and the conservation initiatives taken so far in the country. Red Panda inhabits eastern Himalayan temperate broadleaved forest with bamboo in the understory with an altitudinal range preference of 2400-3900 m. The Red Panda population in Nepal is about 314 individuals. Although the majority of potential habitat i.e. 62% lies in community managed and national forest, a very few initiatives have been started for the research and conservation of this species outside the protected areas. The Red Panda is protected in Nepal. Forest fire, rotational grazing, slash and burn cultivation, timber and fire wood collection, predation by dogs, natural dying of ringal bamboo species, drought, landslide and lack of awareness are identified as the major conservation threats for Red Panda throughout its habitat within the country. Key Words: Community managed forest, Conservation policy, Protected Areas, Red Panda, Threats Introduction The Red Panda is distributed from Nepal in the West through China, India, Bhutan and Myanmar (Ghose & Dutta, 2011). Its westernmost occurrence in Nepal is recorded so far in Mugu District (820E, Sharma, 2008), Western Nepal and eastern most in the Minshan mountains and upper Min Valley of Sichuwan Province, South-Central China (1040E) with a narrow extent of north-south distribution from 250N to 330N (Ellerman & Morrison-Scott 1966, Macdonald 1984, Corbet & Hill 1992, Chaudhary 1997). -

Environmental Education and Perceptions in Eastern Nepal: Analysis of Student Drawings

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION AND PERCEPTIONS IN EASTERN NEPAL: ANALYSIS OF STUDENT DRAWINGS By Sara D. Keinath Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Forestry Michigan Technological University 2004 The project paper: “Environmental Education and Perceptions in Eastern Nepal: Analysis of Student Drawings” is hereby approved in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN FORESTRY. School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science Signatures Advisor: __________________________________ Blair D. Orr Dean: __________________________________ Margaret R. Gale Date: __________________________________ ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vi CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 2 NEPAL Geography and Climate 5 People and Culture 14 Agriculture-based Economy 19 History and Current Situation 22 Education System 26 CHAPTER 3 STUDY AREA: MECHI ZONE 33 CHAPTER 4 ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION 45 CHAPTER 5 METHODOLOGY AND DATA Literature Review 49 Study Design 53 CHAPTER 6 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Description 60 Interpretation 66 CHAPTER 7 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 78 LITERATURE CITED 81 APPENDIX A 89 APPENDIX B 90 iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 1: Class 8 students in Jhapa 1 Figure 2: Reference map of Asia 6 Figure 3: Major geographical regions of Nepal 7 Figure 4: Langtang National Park 8 Figure 5: The middle hills 9 Figure 6: The Terai 10 Figure 7: Royal Chitwan National Park 12 Figure 8: Lumbini, the birthplace of Buddha 13 Figure 9: Road during monsoon -

Plant Biodiversity Inventory, Identification of Hotspots and Conservation Strategies for Threatened Species and Habitats in Kanc

Plant Biodiversity Inventory, Identification of Hotspots and Conservation Strategies for Threatened Species and Habitats in Kanchenjungha-Singhalila Ridge, Eastern Nepal PROJECT EXECUTANT Ethnobotanical Society of Nepal (ESON) 107 Guchha Marg, New Road, Kathmandu, Nepal Ph: 01 - 6213406, Email: [email protected] , web: www.eson.org.np LOCAL COLLABORATORS Shree High Altitude Herb Growers Group (SHAHGG), Ilam & Deep Jyoti Youth Club (DJYC), Panchthar REPORT SUBMITTED TO Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) & WWF Nepal Program September 2008 Plant Biodiversity Inventory, Identification of Hotspots and Conservation Strategies for Threatened Species and Habitats in Kanchenjungha-Singhalila Ridge, Eastern Nepal Ripu M. Kunwar, Krishna K. Shrestha and Ram C. Poudel With the assistance of Sangeeta Rajbhandary, Jeevan Pandey, Nar B. Khatri Man K. Dhamala, Kamal Humagain, Rajendra Rai, Yub R. Poudel Ethnobotanical Society of Nepal (ESON) Karthmandu, Nepal In collaboration with Shree High Altitude Herb Growers Group (SHAHGG), Ilam Deep Jyoti Youth Club (DJYC), Panchthar September 2008 ii Preface The Eastern Himalaya stands out as being one of the globally important sites representing the important hotspots of the South Asia. The Eastern Himalaya has been included among the Earth’s biodiversity hotspots and it includes several Global 200 eco-regions, two endemic bird areas, and several centers for plant diversity. Kanchenjungha-Singhalila Complex (KSC) is one of the five prioritized landscape of the Eastern Himalaya, possesses globally significant population of landscape species. The complex stretches from Kanchenjungha Conservation Area (KCA) in Nepal, which is contiguous with Khanchendzonga Biosphere Reserve in Sikkim, India, to the forest patches in south and southwest of KCA in Ilam, Panchthar and Jhapa districts. -

Government of Nepal

Government of Nepal District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Department of Local Infrastructure Development and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR) District Development Committee, Taplejung Volume I: Main Report September 2013 Prepared by Rural Infrastructure Developers Consultant P. Ltd (RIDC) for the District Development Committee (DDC) and District Technical Office (DTO) Taplejung with Technical Assistance from the Department of Local Infrastructure and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR), Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development and grant supported by DFID District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) of Taplejung District ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to express gratitude to RTI SECTOR Maintenance Pilot for entrusting us on preparation of District Transport Master Plan of Taplejung District. We would also like to express our sincere thanks to Mr. Bharat Mani Pandey, Local Development Officer (LDO) of Taplejung District for his cooperation and continuous support during the preparation of District Transport Master Plan (DTMP). We are thankful to Er. Sushil Shrestha, District Engineer and other concerned officials and staffs from DDC/DTO Taplejung for their support during the DTMP workshops. We thank the expert team who has worked very hard to bring this report at this stage and successful completion of the assignment. We are grateful to the VDC secretary from all VDCs, local people, political parties and leaders, civil society, members of government organizations and non government organizations of Taplejung District who have rendered their valuable suggestion and support for the successful completion of the DTMP. Rural Infrastructure Developers Consultants P. Ltd. (RIDC), Baneshwor, Kathmandu. August 2013 i District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) of Taplejung District EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Taplejung District is located in Mechi Zone of the Eastern Development Region of Nepal. -

Tinjure-Milke-Jaljale Rhododendron Conservation Area a Strategy

Tinjure-Milke-Jaljale Rhododendron Conservation Area A Strategy for Sustainable Development PreparedPrepared in partnershippartnership with IUCN NepalNepal NORM 2010 IUCN Nepal P.O. Box 3923 Kathmandu, Nepal Email: [email protected] URL: www.iucnnepal.org Copy right: © 2010 IUCN Nepal Published by: IUCN Nepal Country Office The role of Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) in supporting IUCN Nepal is gratefully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is permitted without prior written consent from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other non-commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. ISBN: 978-9937-8222-3-7 Available from: IUCN Nepal, P.O. Box 3923, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: (977-1) 5528781, 5528761, Fax: (977-1) 5536786 email: [email protected], URL: http://iucnnepal.org Sponsors Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) The initial draft report was prepared by a team of experts headed by Prof. Dr. Khadga Basnet with support from Mr. Laxman Tiwari (NORM), Mr. Rajendra Khanal, Mr. Meen Dahal, Dr. V.N. Jha and Miss. Utsala Shrestha (IUCN Dharan Office) and Mr. Mingma Norbu Sherpa IUCN Country Office. Table of contents Index of Tables Index of Figures List of Abbreviations/Acronyms Summary .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Fact Sheet....................................................................................................................................... -

Status and Distribution of Red Panda (Ailurus Fulgens Fulgens) in Simsime Community Forest of Papung VDC of Taplejung District, Nepal

Lama Banko Janakari, Vol 29 No. 1, 2019 Pp 25‒32 Status and distribution of Red Panda (Ailurus fulgens fulgens) in Simsime community forest of Papung VDC of Taplejung district, Nepal B. Lama1 Red Panda (Ailurus fulgens fulgens), globally an endangered species of Himalaya, were studied in Simsime community forest of Papung Village Development Committee (VDC) in Taplejung district.. It was carried out to assess status, habitat characteristics and threats to Red Panda. Three transects were laid out along the contours and their total length was 2200 m. The altitude of these transects varied from 2800–3400m. While moving along the transect line, the signs such as pellets, footprints and nests of Red Panda were searched and the GPS points were recorded in those places where the signs were observed. The habitat was assessed simultaneously to describe its characteristics in this community forest. Square plots of 10m * 10m, 4m * 4m and 1m*1m were laid out to assess trees, shrubs and herbs, respectively along contour lines at an altitudinal interval of 200 m between 2800 m and 3400 m and the plots were spaced at a distance of 100 m. Diameter at breast height (DBH) of major tree species (Juniperus spp., Pinus spp., Acer spp. and Rhododendron spp) was measured in the plots. The signs were found in Simsime community forest at an altitude of 3026 m, 3125 m and 3127 m. Overall sign encounter rate for this community forest was 1.36/ km. Acer spp. had the highest Importance Value Index (IVI) and Arundinaria maling was the major bamboo species with highest relative frequency (RF).