Runner-Up Project: Thereâ•Žs Something Happening Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BROADSIDE Hoots Will Be Held Sunday, Jan

1F53 THE NATIONAL TOPICAL SONG l·1A.GAZINE DECEHBER 20, 1964 PRICE -- 50¢ BY @ 1964 PETER Hopi Busic LA FARGE New York jin - "l<t 'fir 'b in +hl!.. +wo- bit CMait-- in' ~( 1:0. '1.Ic.Jc-er just -to +h, .... 1c. +h~t- SY1akes wen.. 0.1 - w--oyr:;. 'Gut the..y Ai~lr r~rtic:.·Il\'" tbout 'the @] fv' r'l t;fhf- o~ of" thU"rl ~S&'cI nell f"1 :r: Tk 1)~~rJ them too at 0. ..f!o.r)- Coy ~lJ. en- Chorl.lS beArd the. (at- ..... le.. e>olllce loud bfld de..3r c.irdJ Dy dib -.q\al1~S ;he.. rattle. - ~nbtes C"l)il f\ : I j , j ~ 0 I jg~ J~ I Cl I .-I .. fJ r~t- +-Ie....- sl'lak~• R. r6t -t\e. sna.ke. noise he-II ~~e ~---- 2. I'Ve heard it too alley's side Where the pushers deal and the addicts glide Heroin's quiet, it enchants the boys But I've heard its anthem and the rattlesnake's noise ~iJ.Jf II Then there's the uptown doctor with his needle clean ra±- He_ st'\a.ke. He's always nice and never mean He gives them dope by another name But I heard the rattlesnake just the same. (Chorus) 3. There's the city official 'way down low Keepin' his pockets full of dough If you want help don't ask his aid There's a rattlesnake sitting in his shade " There's a politician 'way up h!gh ! Too far to hear the people cry ,I Passin' bills for the wealthy men He won't explain but the rattlesnake can. -

Musical Images of the Vietnam War

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 325 431 SO 030 221 AUTHOR Chilcoat, George W.; Vocke, David E. TITLE MusicEl Images of the Vietnam War. PUB DATE Nov 86 NOTE 30p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Council for the Social Studies (Orlando, FL, November 19, 1988). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) -- Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Class Activities; Creative Teaching; Creativity; Curriculum Enrichment; *Drama; *Educational Strategies; High Schools; *History Instrvr'tion; Instructional Materials; Modern History; *Music; Social History; Social Studies; Songs; *United States History; *Vietnam War ABSTRACT Teaciling the Vietnam War in high school history courses is a challenge to the instructor, and study that relies only on textbooks may neglect the controversy surrounding the War and the issues that faced the nation. This v.per discusses how to use songs about the Vietnam War as an instr,.ctional tool to investigate the role of songs during the War and to serve as a stimulus tc study the controversies surrounding the War. Students are challenged to investigate the various perspectives presented these songs and to examine devices utilized within lyrics to support the views they present. Titles and categories of songs that either censured the inhumanity of wars in general and the Vietnam War specifically, or portrayed support for the War in Indochina are included. (NL) *******************************************************************. ** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can te made from the original document. ******************************x**************************************** Musical Images of the Vietnam War U S DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION O.f K e of Edvcahonal Research and Impro.ertent EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER IER ". -

Press Release

6 4 8 7 - 4 “PHIL OCHS: There But For Fortune,” the new film about the iconic folk music hero 8 of the 1960s, has U.S. Theatrical Premiere January 5th in New York at the IFC Center 5 ) National roll out to select cities follows; Advance screenings December 9th 14th & 28th 7 1 Media Contact: Julia Pacetti, JMP Verdant, [email protected], (917) 584-7846 9 ( New York, NY, November 1, 2010 – First Run Features is pleased to invite you and a guest to a special , t advance screening of PHIL OCHS: There But For Fortune, the new film by acclaimed filmmaker e Kenneth Bowser (Easy Riders, Raging Bulls & Live From New York, SNL in the 70’s) about one of the most n . iconic folk music heroes and political agitators in American history. k n As the country continues to engage in foreign wars, PHIL OCHS: There But For Fortune is a timely i l tribute to an unlikely American hero whose music is as relevant today as it was in the 1960s. Ochs, a folk h singing legend, was moved by the conviction that he and his music would change the world. He loved his t r country and fought to honor it, in both song and action. Wielding only a battered guitar, a clear voice and the a quiver of his razor sharp songs, he tirelessly fought the good fight for peace and justice throughout his short e life. @ t i t Phil Ochs rose to fame in the early 1960’s during the height of the folk and protest song movement. -

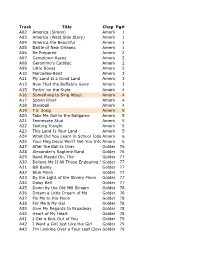

RUS Teaching Disk Track List.Pdf

Track # Title Chap Pg# A02 America (Simon) America 1 A03 America (West Side Story) America 1 A04 America the Beautiful America 1 A05 Battle of New Orleans America 1 A06 Be Prepared America 2 A07 Camptown Races America 2 A08 Geronimo's Cadillac America 2 A09 Little Boxes America 2 A10 Mercedes-Benz America 3 A11 My Land Is a Good Land America 3 A13A12 NowThe NightThat theThey Buffalo's Drove Old Gone Dixie DownAmerica 3 A15A14 Puttin'The Power on the & the Style Glory America 43 A16 Something to Sing About America 4 A17 Spoon River America 4 A18 Stewball America 4 A19 T. V. S o n g America 5 A20 Take Me Out to the Ballgame America 5 A21 Tennessee Stud America 5 A22 Tenting Tonight America 5 A23 This Land Is Your Land America 5 A24 What Did You Learn in School Today?America 6 A25 Your Flag Decal Won't Get You Into AmericaHeaven Anymore6 A27 After the Ball Is Over Golden 76 A28 Alexander's Ragtime Band Golden 76 A29 Band Played On, The Golden 77 A30 Believe Me If All Those Endearing YoungGolden Charms77 A31 Bill Bailey Golden 77 A32 Blue Moon Golden 77 A33 By the Light of the Silvery Moon Golden 77 A34 Daisy Bell Golden 77 A35 Down by the Old Mill Stream Golden 78 A36 Dream a Little Dream of Me Golden 78 A37 Fly Me to the Moon Golden 78 A38 For Me & My Gal Golden 78 A39 Give My Regards to Broadway Golden 78 A40 Heart of My Heart Golden 78 A41 I Get a Kick Out of You Golden 79 A42 I Want a Girl Just Like the Girl Golden 79 A43 I'm Looking Over a Four Leaf CloverGolden 79 A44 I'm Sitting on Top of the World Golden 79 A45 In a Little Spanish -

Book Notes #71

Book Notes #71 August 2021 By Jefferson Scholar-in-Residence Dr. Andrew Roth Songs of Freedom, Songs of Protest Part One As always, reader responses give me ideas for future Book Notes. In this and next week’s Book Notes, I’ll be following the suggestion of several readers who, in response to the two Book Notes in June on patriotic music, thought it might be interesting to canvass America’s tradition of protest music. If one of my The American Tapestry Project’s major threads is “Freedom’s Faultlines”, those tales of race and gender, those tales of exclusion and the many times America did not live up to its stated ideals, then the songs those excluded sang as they fought for inclusion ring patriotic. For, as the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. said in his last speech the night before he was murdered, “Somewhere I read that the greatness of America is the right to protest for right!” [1] And, those “rights” found some of their most memorable expressions in songs of protest exhorting America, as King said, “Be true to what you said on paper.” [2] In this Note, we’ll answer “What is a protest song?”, and we’ll consider three approaches to exploring protest music: a chronological approach, a thematic- genre approach, and although it sounds kind of silly a “Greatest Hits” approach. There actually are “Top Ten”, “Top Fifty” protest song lists from reputable sources floating around the internet. Finally, we’ll dive into two of the genres for a closer look at songs protesting environmental issues and, most famously, anti-war songs from World War I through the War in Viet Nam to Operation Iraqi Freedom. -

Troubadours Folk and the Roots of American Music

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected] Troubadours Folk And The Roots Of American Music INFORMATION In the one hundred years that folk music has been recorded in the United States, the tradition has embraced ballads – mostly new, but some transplanted from Europe, political statements, personal introspection, and much more. Now the story is here from the 1920s to the 1970s and beyond in four exclusive 3-CD sets. Through this music, we feel it all from the isolation of early twen- tieth century Appalachia through the economic and political upheavals of the Depression, War, and Civil Rights eras to contem- porary west coast singer-songwriters looking within for inspiration. The story is here: original artists and original versions in stunning sound with detailed notes from folk scholar Dave Samuelson. The first set covers the period from the 1920s through to 1957. All the names you'd expect are here: the Carter Family, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, the Weavers, Lead Belly, Cisco Houston, and many, many more. Here are the original versions of songs that have become classics and rallying cries: Wildwood Flower, Midnight Special, Rock Island Line, Wayfaring Stranger, So Long It's Been Good To Know You, This Land Is Your Land, 16 Tons, 900 Miles, Delia, and many, many more. The second set begins with the folk revival that started in the wake of the Kingston Trio's Tom Dooley and continues through the dawn of the singer-songwriter era. It includes early folk revival classics like Walk Right In, Michael, and Green, Green. -

Vanguard Label Discography Was Compiled Using Our Record Collections, Schwann Catalogs from 1953 to 1982, a Phono-Log from 1963, and Various Other Sources

Discography Of The Vanguard Label Vanguard Records was established in New York City in 1947. It was owned by Maynard and Seymour Solomon. The label released classical, folk, international, jazz, pop, spoken word, rhythm and blues and blues. Vanguard had a subsidiary called Bach Guild that released classical music. The Solomon brothers started the company with a loan of $10,000 from their family and rented a small office on 80 East 11th Street. The label was started just as the 33 1/3 RPM LP was just gaining popularity and Vanguard concentrated on LP’s. Vanguard commissioned recordings of five Bach Cantatas and those were the first releases on the label. As the long play market expanded Vanguard moved into other fields of music besides classical. The famed producer John Hammond (Discoverer of Robert Johnson, Bruce Springsteen Billie Holiday, Bob Dylan and Aretha Franklin) came in to supervise a jazz series called Jazz Showcase. The Solomon brothers’ politics was left leaning and many of the artists on Vanguard were black-listed by the House Un-American Activities Committive. Vanguard ignored the black-list of performers and had success with Cisco Houston, Paul Robeson and the Weavers. The Weavers were so successful that Vanguard moved more and more into the popular field. Folk music became the main focus of the label and the home of Joan Baez, Ian and Sylvia, Rooftop Singers, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Doc Watson, Country Joe and the Fish and many others. During the 1950’s and early 1960’s, a folk festival was held each year in Newport Rhode Island and Vanguard recorded and issued albums from the those events. -

Abstract Songs in the Key of Protest

ABSTRACT SONGS IN THE KEY OF PROTEST: HOW MUSIC REFLECTS THE SOCIAL TURBULENCE IN AMERICA FROM THE LATE 1950S TO THE EARLY 1970S By Katie M. Laux The Vietnam War polarized the American public. From the late 1950s to the early 1970s, the American public debated nuclear policy, foreign policy, and the war at home. As a result, two social movements emerged, one dedicated to end the war in Vietnam, and the other committed to anti-communism and halting the counterculture. As these two groups battled on American campuses, American musicians on both sides of the debate wrote and performed songs that tried and succeeded in persuading the American public. Their music provides another perspective of the chaos in America caused by the Vietnam War. SONGS IN THE KEY OF PROTEST: HOW MUSIC REFLECTS THE SOCIAL TURBULENCE IN AMERICA FROM THE LATE 1950S TO THE EARLY 1970S A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University In partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts By Katie M. Laux Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2007 Advisor Dr. Allan M. Winkler Reader Dr. Daniel M. Cobb Reader Dr. Amanda K. McVety Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................1 Musical Roots…………………………….................................1 Post-War America……………………………………………..3 American Involvement in Vietnam…………………………....6 Anti-Nuclear, Pacifist, and Anti-Vietnam War Folk Music…...9 American Involvement in Vietnam, 1965 - 1967…………….15 Anti-Vietnam Rock Protest Music……………………………16 Vietnam, 1968 - 1970………………………………………...18 Anti-Vietnam Rock Music, 1968 - 1970……………………..20 The Conservative Movement in the Early 1960s…………….22 Conservative Music, 1965 – 1970…………………………....25 Conclusion……………………………………………………29 ii Introduction Popular music provides a window into society. -

Swarthmore Folk Alumni Songbook 2019

Swarthmore College ALUMNI SONGBOOK 2019 Edition Swarthmore College ALUMNI SONGBOOK Being a nostalgic collection of songs designed to elicit joyful group singing whenever two or three are gathered together on the lawns or in the halls of Alma Mater. Nota Bene June, 1999: The 2014 edition celebrated the College’s Our Folk Festival Group, the folk who keep sesquicentennial. It also honored the life and the computer lines hot with their neverending legacy of Pete Seeger with 21 of his songs, plus conversation on the folkfestival listserv, the ones notes about his musical legacy. The total number who have staged Folk Things the last two Alumni of songs increased to 148. Weekends, decided that this year we’d like to In 2015, we observed several anniversaries. have some song books to facilitate and energize In honor of the 125th anniversary of the birth of singing. Lead Belly and the 50th anniversary of the Selma- The selection here is based on song sheets to-Montgomery march, Lead Belly’s “Bourgeois which Willa Freeman Grunes created for the War Blues” was added, as well as a new section of 11 Years Reunion in 1992 with additional selections Civil Rights songs suggested by three alumni. from the other participants in the listserv. Willa Freeman Grunes ’47 helped us celebrate There are quite a few songs here, but many the 70th anniversary of the first Swarthmore more could have been included. College Intercollegiate Folk Festival (and the We wish to say up front, that this book is 90th anniversary of her birth!) by telling us about intended for the use of Swarthmore College the origins of the Festivals and about her role Alumni on their Alumni Weekend and is neither in booking the first two featured folk singers, for sale nor available to the general public. -

FROM “WE SHALL OVERCOME” to “FORTUNATE SON”: the EVOLVING SOUND of PROTEST an Analysis on the Changing Nature of American Protest Music During the Sixties

FROM “WE SHALL OVERCOME” TO “FORTUNATE SON”: THE EVOLVING SOUND OF PROTEST An analysis on the changing nature of American protest music during the Sixties FLORIS VAN DER LAAN S1029781 MA North American Studies Supervisor: Frank Mehring 20 Augustus 2020 Thesis k Floris van der Laan - 2 Abstract Drawing on Denisoff’s theoretical framework - based on his analysis of the magnetic and rhetorical songs of persuasion - this thesis will examine how American protest music evolved during the Sixties (1960-1969). Songs of protest in relation to the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War gave a sound to the sociopolitical zeitgeist, critically addressing matters that were present throughout this decade. From the gentle sounds of folk to the dazzling melodies of rock, protest music became an essential cultural medium that inspired forms of collective thought. Ideas of critique and feelings of dissent were uniquely captured in protest songs, creating this intrinsic correlation between politics, music, and protest. Still, a clear changing nature can be identified whilst scrutinizing the musical phases and genres – specifically folk and rock - the Sixties went through. By taking a closer look on the cultural artifacts of protest songs, this work will try to demonstrate how American songs of protest developed during this decade, often affected by sociopolitical factors. From Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” to The Doors’ “The Unknown Soldier”, and from “Eve of Destruction” by Barry McGuire to “Superbird” by Country Joe and The Fish, a thorough analysis of protest music will be provided. On the basis of lyrics, melodies, and live performances, this thesis will discuss how protest songs reflected the mood of the times, and provided an ever-evolving destabilizing force that continuously adjusted to its social and political surroundings. -

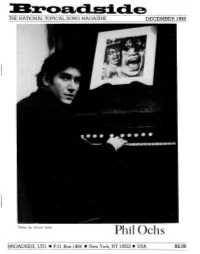

To Read Broadside

• -ad.sic:l.e THE NATIONAL TOPICAL SONG MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1983 Photo by Alice Ochs PhilOehs BROADSIDE, LTD .• P.O. Box 1464 • New York, NY 10023 • USA $2.00 2 lBx-<:>adside #147 BROADSIDE #147 The National Topical Song Magazine Published monthly by: Broadside, Ltd. P.O. Box 1464 New York, NY 10023 Publisher Norman A. Ross Editor Jeff Ritter Assistant Editors Gordon Grinberg Robin Ticho Contributing Editors Jane Friesen Paul Kaplan Sonny Ochs Ron Turner Illustrations by Agnes Friesen Kenneth E. Klammer Jane Ron Sonny Paul Poetry Editors D. B. Axelrod Friesen Turner Ochs Kaplan lC. Hand Editorial Board Sis Cunningham Gordon Friesen ISSN: 0740-7955 <D 1983, BROADSIDE LTD. Phil This issue of Broadside is a tribute to Phil Ochs, works, one of which is his song about Raygun's who would have been 43 years old on December invasion of Grenada! Finally, this issue contains six 19th. Phil was one of Broadside's most frequent songs "written" by Phil but never previously pub contributors over the years: the Index to Broadside lished either in print or on a record. These songs lists more than 70 of Phil's songs. Furthermore, the were among 15 or more that Phil sent on tape many pages of Broadside over these years were filled with years ago to his long-time friend Jim Glover and items by and about Phil and with songs written by which had been forgotten. Having recently redis Phil's contemporaries, many of whom were inspired covered them, Jim gave copies to Broadside (with by Phil--as we all were. -

An Intimate Look Back at 1968

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2019 Nothing Is Revealed: An Intimate Look Back at 1968 Aaron Barlow CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/462 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Nothing Is Revealed An Intimate Look Back at 1968 Aaron Barlow Cover Photo by Atlas Green (CC0) Published by: Brooklyn, NY 2019 ISBN-13: 9781697690675 PUBLISHED UNDER AN ATTRIBUTION-NONCOMMERCIAL-SHAREALIKE CREATIVE COMMONS LICENSE ii For all of those who didn’t make it far enough to be able to look back ii Introduction This project isn’t simply one of memoir. It’s a cultural study from a personal base, one created, also, through a unique temporal framework, a moving narrative composed of blog posts each focused on the exact day fifty years earlier. Its sub- jectivity is deliberate, for the intent is to provide an impression of a significant year through the eyes of a young man in the process of coming of age. It’s also a political tale sparked by the rise of Donald Trump to the Presiden- cy of the United States, one detailing the seeds of that rise and the false populism and white nationalism that are still buoying him in 2019. Sexual violence. Racial violence. Political violence.