ABSTRACT in Paradise: a Feature Film Philip Heinrich, 0.A. Advisor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021-22 Bulletin: Graduate School Of

2021–22 Bulletin Graduate School of Art Bulletin 2021-22 Table of Contents (07/22/21) Table of Contents About This Bulletin .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 About Washington University in St. Louis ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Trustees & Administration ........................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Academic Calendar .................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Campus Resources .................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 University Policies .................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 University Affiliations .............................................................................................................................................................................. 12 Graduate School of Art ................................................................................................................................................................................ -

IPMS April 2015

PREZNOTES IPMS Seattle Spring Show 2015 Show Calendar Needs YOU! Thanks to Chellie Lynn This Saturday at the Chapter meeting we need to sign up more members to help out 4/11/2015 Lynnwood Galaxy with the Spring Show. With 100 or so paid 4/18/2015 Portland 25th Model Car up members, you would think it would be Fest a cinch to pull off a model show, even one 4/25/2015 Renton IPMS Seattle the size of the IPMS Spring Show. But it 5/3/2015 Puyallup MCS 26 simply isn’t. Our Show is a big deal, and 6/27/2015 Chehalis Billetproof requires a massive amount of bodies to 6/27/2015 Kitsap Fair NOPMS make it work effectively. 7/24-26/2015 Puyallup Good Guys 7/22-25/2015 Columbus OH IPMS By effectively, I mean that in order to get Nationals folks to volunteer, we don’t want to be a burden by requiring them to work so hard, and for so long, that they can’t personally enjoy the show. We need to balance out the effort, so that while people volunteer to work the event, they also can find time to shop with the vendors, and view all the lovely models on display. This means limiting folks to working less than half the show time, so that they can spend the other half, well, NOT working. Otherwise next year, having been overburdened, folks will baulk at the idea of putting on a show. Seattle Chapter News So if you want this Show to continue, if you want to have fun helping people out, while at the same time enjoying a great day at the region’s largest scale model contest and show, please sign up for a task slot or two at one of these areas: Registration or Raffle (both provide a seat In This Issue to sit on), Hosting, or Judging. -

The Estranged Object Young & Ayata Kutan Ayata Michael Young

THE ESTRANGED OBJECT YOUNG & AYATA KUTAN AYATA MICHAEL YOUNG THE ESTRANGED OBJECT Contents Introduction: 5 The Nature of the Real Rhett Russo An Aesthetics of Realism 19 The Morning Cleaning 22 Estrangement & Objects 29 Aesthetic Regimes of the Sensible 32 Speculative Objects 39 Realism and Medium Specificity 47 Photography and Estrangement through Absorption 53 The Parafictional and Medium Promiscuity 65 One or Many Mediums 76 Young & Ayata: 1. Drawings 79 2. Objects 85 3. Buildings 91 Introduction: The Nature of the Real Rhett Russo The challenges associated with depicting the real have played an important role in cinema, literature, art, sculpture, and philosophy, but have yet to be fully exploited by architecture. Nonetheless architecture shares many of the same ontological predicaments with these other arts—the introduction of iron, the invention of photography, and the Industrial Revolution are a few examples of crucial developments, which have significantly challenged classicist doctrine. The realist painting of the 1850s, in particular works by Gustave Courbet, confront the viewer with the realities of labor in a new way. With Courbet, reality is presented through the tensed body of the kneeling peasant in Sifting Wheat (1854) or the brokenhearted embodiment of the Wounded Man (1854). Similarly, the emaciated travelers depicted in the Raft of the Medusa (1818–19) emerged from Gericault’s careful practice of painting dead corpses—and seizing the opportunity to speculate on the aesthetics of historical events. These unusual practices formed the core in the developing aesthetic category of the “real.” As Michael Fried has remarked, the content of realist painting presents a particular challenge for historians, due in part to the shift in emphasis toward depicting the “everyday,” but also Rhett Russo Rhett Russo because its resultant strangeness dislodged it from the framework at the moment of its crew’s rescue. -

Graduate School of Art (09/09/21)

Bulletin 2021-22 Graduate School of Art (09/09/21) Graduate School of F10 ART 542 Graduate Studio Graduate studio work emphasizes individual development through a mix of independent study and activities structured Art around shared student and faculty interests. The direction of student artwork is determined through consultation with Email: [email protected] faculty, and faculty act as guides to realize objectives set by the student. Faculty provide critical commentary through ongoing Website: https://samfoxschool.wustl.edu/ dialogue with students and facilitate dialogue expanded by group academics/college-of-art critiques, contact with visiting artists, and museum and gallery trips. Graduate students are encouraged to explore traditional Courses and experimental approaches to art making. Credit 10 units. EN: H • F10 Art: Art foundation and major studio courses • F20 Art: Art elective courses F10 ART 542A Graduate Studio Graduate studio work emphasizes individual development through a mix of independent study and activities structured F10 Art around shared student and faculty interests. The direction of student artwork is determined through consultation with Visit online course listings to view semester offerings for faculty, and faculty act as guides to realize objectives set by the F10 ART (https://courses.wustl.edu/CourseInfo.aspx? student. Faculty provide critical commentary through ongoing sch=F&dept=F10&crslvl=5:6). dialogue with students and facilitate dialogue expanded by group critiques, contact with visiting artists, and museum and gallery trips. Graduate students are encouraged to explore traditional F10 ART 541 Graduate Studio and experimental approaches to art making. Graduate studio work emphasizes individual development Credit 9 units. -

Central Valley Bridge Kitbash

Price: Forever Free PRINTER-FRIENDLY Edition November 2011 - IN DEPTH: Moving coal Tom Patterson does a - Stripping Kato paint - Improving Atlas crossovers Central Valley - Canvas curtains from teabags Bridge Kitbash and lots more, inside ... Page 1 • Issue 11-11• Nov 2011 Front cover Front Cover: MRH forum regular Tom Patterson shows us how he beefed up a Central Valley truss bridge to make it more suitable for heavy coal train mainline traffic on his CVE railroad. Read all about what Tom did in this issue. Cover photo by Tom Patterson. ISSN 2152-7423 Editorial Staff Joe D. Fugate, Publisher Charlie Comstock, Editor Columnists Richard Bale, News and events Remember to tell them: “MRH sent me!” John Drye, N scale Lew Matt, Narrow gauge and shortlines Bruce Petrarca, DCC Sponsoring Advertisers - Les Halmos, Modular railroading Our sponsors get extra visibility with the Special Correspondents Jim Duncan, Layouts and operations MRH web audience (45,000+). There’s also our Hobby Marketplace! see page 22 ... Byron Henderson, Layouts and track planning For more model Production Patty Fugate, pasteup and layout railroading Joe Brugger, copy editing Mike Dodd, copy editing products, including Technical Assistant hard-to-find items, Jeff Shultz also see our Advertising Account Manager Hobby Marketplace Les Halmos Click here to learn how to become on page 22. a sponsoring advertiser. Page 2 • Issue 11-11• Nov 2011 Masthead and Sponsors Page 3 • Issue 11-11• Nov 2011 Advertisement Visit BLMA website LAST CHANCE Click before they disappear. HUNDREDS -

Mainline Modeler 1992

NEW UP, GN, C&NW SETS Our spring releoses are: UP 5450/CNW 3477 ACF 44-soot choir cars, Gel smoother Running Models $24.75. UP5900/C&NW 8225/GN 37·44ACF baggago·mail with 6 soparoto etched door pioces in two sizes, $30.75 . With oualilY NWSL Whee1se1s1 W o solicit reservations from doalers ond individuals for tho following HO phototched brass side sots being considerod for 1992: ess friction and drag C&O/D&AGW/SAL/C&NW holf·fluted PS coaches (Plan 7600) with Evergreen fluting. means improved pulling NYC 2600 PS 56-saat coaches. Lpower: See how smooth IC 2600.sories "City" PS coaches. your equipment will roll with Send a largo SSAE (52e) for our catolog and bulletin showing 42 side sets (6 for dome cersl custom quality wheelsets end body kits for over 30 roads. Available from NWSL. through hobby shops or direct (add $3.50 shipping). Dealer inquiri es invited. NWSL wheelsets are avial able in HO, HOn3, Sn3, On2, BRASS CAR SIDES 716 S, 7th St. Peter, MN 66082 On3, & 0 gauges. Wheelsizes range from 26" to 42" in a variety of tread and axle styles . All wheelsets are precision machined, non-magnetic, nickle plated brass (except 0 gauge, which are chemically blackened steel) and each is individually inspected to assure a true, concentric, wobble-free, efficient rolling wheelset. Also available are the special " Half-axle" replacement wheelsets for Athearn HO scale diese ls which provide COMPUTERIZED ARTWORK SERVICE WHEELSET STYLES improved performance and eliminate those pesky dirty wheel/ electrical pick-up problems. -

Mrr 199402.Pdf

TH( PROTO 2000 (8: TH( 6(NIUS IS IN TH( D(TAILS. 8&0 All of them. In fact. 170 there's never been a locomotive so precisely Two locomotive numbers per detailed and as proto road name. typically accurate as the new PROTO 2000 ES/9. So true to life in styling ............. ...... U'-=�:" ..::;==== - =--- and performance that it .. :;;;:-== (= It will change the way you I IHllle I think about model .........l N ��-.--ION [ railroading. With its all new body. the is the first ES/9 UP of its kind to feature accurate detail by road on everything Also available in: ATSF. Amtrak. Demo name from pilots to steam and Undecorated. generators. headlights to grilles. And. like the prototype. our is exceptionally ES powerful. with innovative six-wheel trucks designed to enhance all-wheel traction and electrical pick-up. The PROTO tradition continues with the new 2000 See it today at your favorite hobby store. ES/9. PRR OVER 110 DETAIL PARTS AND MORE • Working diaphragm. Mars light and doors. An engine so powerful it • can haul 135-150 on a level track. • See-thru steps. fan grilles. screening on cars winterization hatches. Can climb an uphill grade of over and • 23% can easily pull cars up a grade. • Photo-etched stainless steel grilles. 22 Lj% • Diecast chassis for maximum • Laser printed paint schemes and decoration. tractive effort. • Detailed cab interior with crew. • Sintered bronze oilless High-performance motor with superrite • bearings. Dual machined anisotropic magnets, pole skew wound 5 fly-wheels. Universal coupler armature, and low amp draw. pockets. A NtflSllMItd.£rrtllt«Ii.Hf)StIlt L&N Life-Like Products, Inc., Union Avenue. -

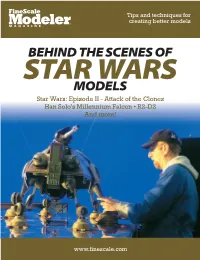

Behind the Scenes of Models

Tips and techniques for creating better models BEHIND THE SCENES OF STAR WARS MODELS Star Wars: Episode II - Attack of the Clones Han Solo’s Millennium Falcon • R2-D2 And more! www.finescale.com I I Peggy Hrastar details miniature towers for the Geonosis arena Steve Belleci details a model of a Kamino building. In Attack of sequence. The desolate planet Geonosis is the setting for some the Clones, Obi-Wan Kenobi visits the rain-swept world of spectacular sequences, including the sweeping first battle of Kamino and discovers its secret clone-production facilities. the movie's clone war. From left: Aaron Haye, Tom Ehline, and Grant lmahara work on Charlie Bailey details a section of the Geonosis android factory a Dexter's Diner model. miniature. A big challenge. "I am proud of my accomplishments on state-of-the-art workshops, which are stocked with a seemingly Episode II," Brian says. "The scale, scope, timing, level of detail, endless variety of tools and raw materials. and speed that this project was done on was unsurpassed. "When ILM was getting started, everything was done by "We cranked out a massive amount of work in a very short hand, or kitbashed," he says. "All the foam and wood patterns period of time. At our peak we had about 80 model makers. We were hand-carved or hand-sculpted. We had people there who did somewhere in the neighborhood of 150 to 200 miniatures made wooden propellers by hand, without a template. and models." "Now we use CNC [computer numerically controlled] mills for According to Brian, it took about 18 months to build the a lot of the work, and we're really focusing on laser cutting and models for Episode II. -

World Watch One Newsletter (January 2021)

WORLD WATCH ONE IN THIS ISSUE Introduction from Dan “Big Shoulders” Berger, the Editor Libertyville, IL Page 1 In Memoriam: Steve “Rainbow Kitty” Mattsson Jerry Peterson Portland, OR Page 2 Beauty in Everyday Life Rich “Octopodes” Ross Alameda, CA Page 3 Camping & All Weather Colleen “Lady Chills” Method Go-Bag Extras Indianapolis IN Page 4 INTERVIEW: Bruce McCorkindale Dan Berger Pages 5-6 Buckaroo Banzai Sean “Figment” Murphy Action figures! Burke, VA Pages 7-12 Banzai Institute BBI Rolo Tomasi, Christmas Post Card Somewhere in Southern California Page 12 EXTENDED CUT: Bootleg Toys Sean Murphy Page 13 FAN FOCUS: Karl Lundstedt Dan Berger Page 14 The Buckaroo Barrier Steven “Green Town” Silver Deerfield, IL Pages 15-16 Lizardo (Undercover!) Sean Murphy Pages 17-18 INTERVIEW: Laura Harrington Steve Mattsson Pages 19-21 Continuity Polaroids Steve Mattsson Page 22 The Mrs. Johnson Dan Berger & Sean Murphy Compendium with Steve Mattsson Pages 23-30 Catching up with Vetted for publication Mrs. Johnson by Reno of Memphis Pages 31-32 Coming Attractions Scott “Camelot” Tate Alamosa, CO Pages 33-34 BOOK REVIEW: The Art of Star Trek Discovery Scott Tate Pages 35-36 INTERVIEW: Terry J. Erdmann Scott Tate Pages 37-39 BOOK REVIEW: A Dollop of Toothpaste Scott Tate Page 40 INTERVIEW: Billy Vera Scott Tate Page 41 From the Bureau Office Scott Tate & Dan Berger Page 42 A Salute to 2021 Dan Berger Page 43 Mrs. E. Johnson Karl Lundstedt Back Cover Acknowledgements This was something of an unexpected issue. Way back in the summer of 2020, a collection of articles began to take shape intended for this issue, along with several other pieces in development. -

Download Various Other Resources from the Internet and Modify Them As Needed

Acta Ludologica Faculty of Mass Media Communication Vol. 4,Vol. No. 1 Theory Education Design Development Research June 2021 History Marketing Experience Criticism Psychology Social Aspects Future Editorial Board Editor-In-Chief Zdenko Mago Deputy Managing Editors Zuzana Kvetanová Martin Solík Indexing Process Zuzana Kvetanová Technical Editors Zuzana Kvetanová Zuzana Točená English Editor Michael Valek Distribution Miroslav Macák Online Content Manager Johny Domanský Advisory Board Peter A. Bruck Koichi Hosoi Zora Hudíková Małgorzata Łuszczak Juraj Malíček Hana Pravdová Jaroslav Světlík Masayuki Uemura Editorial Team Anna Hurajová Michal Kabát Nikola Kaňuková Illustrations Zdenko Mago Graphic Production Coordinator & Cover Martin Graca Martin Klementis Journal Orientation Acta Ludologica is a scientific journal in the field of games and digital games. The journal contains professional sci- entific reflections on digital games; it also offers academic discourses on games, especially media and digital com- petencies, creation, design, marketing, research, devel- opment, psychology, sociology, history and the future of digital games and game studies. Acta Ludologica is a double-blind peer reviewed journal published twice a year. It focuses on theoretical studies, theoretical and empirical studies, research results and their implementation into practice, as well as professional publication and scientific reviews of digital games. Acta Ludologica Vol. 4, No. 1, June 2021 Publisher Faculty of Mass Media Communication University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius in Trnava Námestie Jozefa Herdu 2 917 01 Trnava SLOVAK REPUBLIC IČO: 360 789 13 Price: 1,99 € Published twice a year. ISSN 2585-8599 e-ISSN 2585-9218 EV 5620/18 ACTA LUDOLOGICA Editorial “Great stories happen what will happen next; it is so outstanding be- to those who can tell cause the player feels that their in-game choices really matter. -

TSC Artile Guide List

VOLUME 1 Vol. 1:1 Modifying an Early American Secretary Kit (Realife 228) Modern Wegner Folding Chair Oriental Rug Knotting Hunting the Victorian Cabriole with Knife and Dental Burr Victorian Rococo Settee Linear Measurement & Tools The Whitman House, Part 1 Miniature Rooms: A Point of Reference Why Scale?: An Editorial Essay Vol. 1:2 The Slaw Bed: An 18th Century Murphy Basswood: maddening, Maligned, and Indispensable American Secretary Kit Modification, Part 2 Easier by the Dozen: The Parson's Table Miniature Rooms: A Different Point of View Cutting Queen Anne Cabriole Leg Blanks Smithfield Plantation Roundabout Chair Curvilinear Measurement & Scale Conversion Chart Art Nouveau Parlor Cabinet The Whitman House, Part 2 Vol. 1:3 Modeling From Prototype: 17th Century Gateleg Table The Whitman House, Part 3 Shaker Pedestal Stand Working with the Dremel Moto-lathe Introduction to Hand-Woven Caning Caning: Victorian Factory Side Chair Caning Contemporary Bamboo Headboard Bargello: Miniatures in Flame Victorian Transitional Side Chair Practice in Rushing and Turning: Shaker Ladderback Chair Kitbashing X-Acto's Cupboard and Drysink Vol 1:4 The Whitman House, Conclusion Dying with Natural Dyes Leisure Furniture in the Early 1900's Porch Swing Adirondack Chair Folding Desk Chair Modeling A Farm Kitchen (Kitbash)Part 1 Realife Icebox Cabinet Sink Range Utility Table Woodturning On the Metalworking Lathe: part 1, Chisels Casebound Bookbinding in Miniature VOLUME 2 Vol. 2:1 Miniature Dimension & The Architect Scale Christmas Toys The Pulltoy Doll Carriage & Grenier Doll Marbling Paper for Miniature Books Intro. To Embroidery on Canvas A Tomorrow Rug Woodturning on a Metalworking Lathe: Part 2, From Hand to Machine Control Chippendale in Suburbia Carving A Ball & Claw Foot on a Cabriole leg Chippendale Tea Table Kitbashing X-Acto's Arm and Side ChairWing Chair, and Sofa Modeling A Farm Kitchen, part 2 Caning: Late Empire Couch Vol. -

From Concept to Publication #1

Left & Previous Page: While an article on kitbashing this one-of-a-kind fire car would appeal to Central of New Jersey and Conrail fans, the rest of the model- ing community would likely have little use for it. They might, however, have an interest in how the scratchbuilt side sills were constructed, enabling those techniques to be used on projects such as build- ing a flatcar. Both Above: These two identical photos illustrate the relation between aperture and depth of field. The top photo was taken at f5 while the photo and the lower image was captured at f32, showing the deeper depth of field. The trade off is longer exposure needed to properly expose the image. It is almost impossible to hand hold an image captured at f32. subject may be ideally suited to a historical society, a broad audience may find its scope too narrow, leading us to the next question: 2. Can or should the audience be ex- panded by demonstrating different tech- niques within the context of the project, en- abling the reader to apply these in their own pursuits? For example, while one may not have any interest in that particular boxcar, learning how two cars were spliced together to create it may provide something that can be used in other endeavors. These two basic questions should dictate the direction to proceed while as- From Concept to Publication sembling the various elements that will Poor DePth of fielD comprise a potential article, the first being CauseD by low f-stoP photography. Photography — likely the (f5) setting.