(CAJ) in Relation to the Supervision of the Cases Concerning the Actions of the Security Forces in Northern Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barnard's (Edward) Application for Judicial Review of The

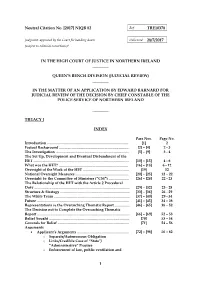

Neutral Citation No. [2017] NIQB 82 Ref: TRE10378 Judgment: approved by the Court for handing down Delivered: 28/7/2017 (subject to editorial corrections)* IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE IN NORTHERN IRELAND ________ QUEEN’S BENCH DIVISION (JUDICIAL REVIEW) ________ IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION BY EDWARD BARNARD FOR JUDICIAL REVIEW OF THE DECISION BY CHIEF CONSTABLE OF THE POLICE SERVICE OF NORTHERN IRELAND ________ TREACY J INDEX Para Nos. Page No. Introduction ........................................................................................ [1] 2 Factual Background ........................................................................... [2] – [4] 2 - 3 The Investigation .............................................................................. [5] – [9] 3 - 4 The Set Up, Development and Eventual Disbandment of the HET ....................................................................................................... [10] – [15] 4 - 6 What was the HET? ........................................................................... [16] – [18] 6 - 12 Oversight of the Work of the HET .................................................. [19] 12 National Oversight Measures .......................................................... [20] – [25] 12 – 22 Oversight by the Committee of Ministers (“CM”) ...................... [26] – [28] 22 - 23 The Relationship of the HET with the Article 2 Procedural Duty ....................................................................................................... [29] – [32] 23 - 25 Structure -

Dziadok Mikalai 1'St Year Student

EUROPEAN HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY Program «World Politics and economics» Dziadok Mikalai 1'st year student Essay Written assignment Course «International relations and governances» Course instructor Andrey Stiapanau Vilnius, 2016 The Troubles (Northern Ireland conflict 1969-1998) Plan Introduction 1. General outline of a conflict. 2. Approach, theory, level of analysis (providing framework). Providing the hypothesis 3. Major actors involved, definition of their priorities, preferences and interests. 4. Origins of the conflict (historical perspective), major actions timeline 5. Models of conflicts, explanations of its reasons 6. Proving the hypothesis 7. Conclusion Bibliography Introduction Northern Ireland conflict, called “the Troubles” was the most durable conflict in the Europe since WW2. Before War in Donbass (2014-present), which lead to 9,371 death up to June 3, 20161 it also can be called the bloodiest conflict, but unfortunately The Donbass War snatched from The Troubles “the victory palm” of this dreadful competition. The importance of this issue, however, is still essential and vital because of challenges Europe experience now. Both proxy war on Donbass and recent terrorist attacks had strained significantly the political atmosphere in Europe, showing that Europe is not safe anymore. In this conditions, it is necessary for us to try to assume, how far this insecurity and tensions might go and will the circumstances and the challenges of a international relations ignite the conflict in Northern Ireland again. It also makes sense for us to recognize that the Troubles was also a proxy war to a certain degree 23 Sources, used in this essay are mostly mass-media articles, human rights observers’ and international organizations reports, and surveys made by political scientists on this issue. -

Over Ten Years of Cover-Ups Left Nineteen People Dead

Irelandclick.com January 22 2007 Site Search DailyIreland.com Advanced Home As of 11th April 2006, www.dailyireland.com, incorporating www.irelandclick.com is Registered with ABC ELECTRONIC (www.abce.org.uk) and supports industry agreed standards for website News traffic measurement Comment Sport Over ten years of cover-ups left nineteen Features people dead ------------------------- RUC’s Special Branch gave Mount Vernon UVF a licence to kill Lá North Belfast News ------------------------- By Ciaran Barnes Downloads 19/01/2007 ------------------------- Andersonstown News 17 January 1993, Sharon McKenna: Two former policemen claim Mark Haddock told them he shot Shraon Home McKenna dead at the house of an elderly Protestant friend on the Shore Road. News Jonty Brown and Trevor McIlwrath claim Special Branch blocked attempts Comment by them to charge the UVF men involved despite the detectives having the confession. Sport Features 24 February 1994, Sean McParland: Murdered by a UVF Special Branch agent from Newtownabbey nicknamed ------------------------- the Beast. The paramilitary is the current boss of the organisation in Southeast Antrim. North Belfast News No one has been charged with the killing. Home News 17 May 1994, Eamon Fox and Gary Convie: The Catholic builders were allegedly shot dead by Haddock as they worked on a building site in Tiger's Comment Bay. Despite admitting to Special Branch handlers that he was involved Haddock was never charged. Sport Features 17 June 1994, Cecil Dougherty and William Corrigan: The Protestant builders were shot dead in a hut on a construction site in Rathcoole. They ------------------------- were mistaken for Catholics. South Belfast News The killing was carried out by a paramilitary who was trying to wrest control of the Southeast Antrim UVF from Haddock, shooting the men while Home his boss was on holiday. -

Sinn Féin Ard Fheis 2014 Dé Haoine 7Ú & Dé Sathairn 8Ú Feabhra, Loch Garman Friday 7Th & Saturday 8Th Febuary, Wexford Bí Le Shinn Féin / Join Sinn Féin

Clar 2014 Cover spread no spine 24/01/2014 11:36 Page 1 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis 2014 Dé hAoine 7ú & Dé Sathairn 8ú Feabhra, Loch Garman Friday 7th & Saturday 8th Febuary, Wexford Bí le Shinn Féin / Join Sinn Féin Bí le Téacs / Join by Text: Seol an focal SINN FEIN ansin d’ainm agus seoladh chuig / Text the word SINN FEIN followed by your name and address to: 51444 (26 Chondae / 26 counties) 60060 (6 Chondae / 6 counties) Ar Líne / Join online: www.sinnfein.ie/join-sinn-fein PUTTING IRELAND Sinn Féin Sinn Féin 44 Cearnóg Pharnell, 44 Parnell Square, Baile Átha Cliath 1, Éire. Dublin 1, Ireland. FIRST Tel: (353) 1 872 6100/872 6932 Tel: (353) 1 872 6100/872 6932 Fax: (353) 1 889 2566 Fax: (353) 1 889 2566 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] ÉIRE CHUN TOSAIGH Sinn Féin Sinn Féin 53 Bóthar na bhFál, 53 Falls Road, Béal Feirste, BT 12PD, Éire. Belfast, BT 12PD, Ireland. Tel: 028 90 347350 Tel: 028 90 347350 Fax: 028 90 347386 Fax: 028 90 347386 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] www.sinnfein.ie www.sinnfein.ie SFAF Clar 2014.qxd 24/01/2014 11:34 Page 1 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis 2014 Wexford Friday 7th February 16.00 » Registration 18.00 » David Cullinane Opening 18.15 » Economy • Decent Work for Decent Pay Motions 1-13 | Pages 5-8 • Reducing the Tax Burden on Ordinary Workers Motions 14-19 | Pages 8-10 • Protecting the Conditions of those in Work Motions 20-21 | Pages 10-11 • Economic Sovereignty Motions 22-25 | Pages 11-13 19.00 » Keynote Address from Martin McGuinness 19.15 » Peace Process • Dealing with the Legacy of -

Written Answers to Questions Official Report (Hansard)

Written Answers to Questions Official Report (Hansard) Friday 17 February 2012 Volume 72, No WA2 This publication contains the written answers to questions tabled by Members. The content of the responses is as received at the time from the relevant Minister or representative of the Assembly Commission and has not been subject to the official reporting process or changed in any way. Contents Written Answers to Questions Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister ............................................................... WA 195 Department of Agriculture and Rural Development .................................................................. WA 202 Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure ................................................................................ WA 210 Department of Education ...................................................................................................... WA 219 Department for Employment and Learning .............................................................................. WA 255 Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment .................................................................... WA 263 Department of the Environment ............................................................................................. WA 279 Department of Finance and Personnel ................................................................................... WA 285 Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety ......................................................... WA 289 Department -

THE APPARATUS of IMPUNITY? Human Rights Violations and the Northern Ireland Conflict: a Narrative of Official Limitations on Post-Agreement Investigative Mechanisms

THE APPARATUS OF IMPUNITY? Human rights violations and the Northern Ireland conflict: a narrative of official limitations on post-Agreement investigative mechanisms Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) © Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The material may be reproduced, free of charge, in any format or medium without specific permission, provided the reproduction is not for financial or material gain.The material must be reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. If the material is to be republished or issued to others, acknowledgement must be given to its source, copyright status, and date of publication. This publication is available on our website. CAJ Committee on the Administration of Justice 2nd Floor, Sturgen Building 9-15 Queen Street Belfast BT1 6EA Tel: 028 9031 6000 Fax: 028 9031 4583 [email protected] www.caj.org.uk ISBN 978 1 873285 94 7 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) THE APPARATUS OF IMPUNITY? Human rights violations and the Northern Ireland conflict: a narrative of official limitations on post-Agreement investigative mechanisms Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) Recent comments from key Council of Europe and UN human rights bodies in relation to existing mechanisms investigating the conflict in Northern Ireland: The absence of any plausible explanation for the failure to collect key evidence at the time when this was possible, and for attempts to even obstruct this process, should be treated with particular vigilance. -

Born on One Side of Partition: Reassessing Lessons Of

Executive Master’s in International Politics 2019-2020 Born on One Side of Partition: Reassessing Lessons of Northern Ireland’s Conflict from a st 21 -Century Multidisciplinary Perspective By JACQUELINE NOLAN Supervisor PROFESSOR GUY OLIVIER FAURE Professor of International Negotiation, Sorbonne University October 2020 i “History says, don’t hope On this side of the grave. But then, once in a lifetime The longed-for tidal wave Of justice can rise up, And hope and history rhyme." (Seamus Heaney, ‘The Cure at Troy’) The question is: whose history? ii Abstract In the wake of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which brought an end to 30 years of conflict in Northern Ireland, the province became a ‘place of pilgrimage’ for people from other conflict zones in search of lessons and answers. This thesis revisits Northern Ireland’s lessons from a multidisciplinary and 21st-century perspective; it contends that to make sense of and resolve a conflict in a sustainable way, you have to not only under- stand it through substantive lenses, but also through emotional and behavioural ones – and likewise understand the interconnectedness between those lenses. It identifies relational and deep-seated themes common to other conflicts (like Israel-Palestine): de- monization, a siege mentality, the historical context of rifts in the relationship. Northern Ireland offered images of hope when former arch-enemies entered government together in 2007; yet this thesis shows that, in spite of political and social transformation, there is still too much societal psychological trauma, and too many unspoken, legacy- and identity-based blockers in the relationship to speak of a conflict resolution. -

Glenanne Gang’ Member’S Death a Reminder of British State Collusion

Sinn Féin: ‘Glenanne Gang’ member’s death a reminder of British state collusion Background Policies Peace Process Elections Join/Donate Newsroom English/Gaeilge Newsroom Daily news Latest News from Sinn Féin Archives ‘Glenanne Gang’ member’s death a reminder of Special Features British state collusion Audio/Video Ireland's most popular political Podcast weekly Campaign Other newspaper online. Published: 27 May, 2008 Literature stories for 27 May, 2008 RSS Feed Newry and Armagh MP Conor Murphy commenting on the death of 'Glenanne Gang' member James Mitchell has said that it is a reminder of the collusion between British state forces ● 2,500 Dogs Books, videos, and unionist death squads. impounded by CDs, shirts and Newry and much more Subscribe to our all available online. Mourne Council new email news Mr Murphy said: service & ● Ferris multimedia news "The death of 'Glenanne Gang' member James Mitchell is a highlights centre. issue of fuel reminder of the issue of British state forces collusion with If you live outside costs for unionist death squads. The Glenanne Gang carried out some of Ireland you can of the most notorious sectarian killings on both sides of the fishermen still play your part. border. There is compelling evidence that senior members of ● Sinn Féin British state forces, in particular RUC officers, UDR soldiers Introduces and their agents, were involved in these sectarian murders. Trade Union Recognition Bill "James Mitchell was named along with other Glenanne Gang members in the Barron Report of 2003 into bombings in ● Charter of Dublin and Monaghan. There is credible evidence that their Fundamental activities were known and supported, tacitly and in some Rights will not cases explicitly, by some of their RUC and UDR superiors and protect by British intelligence and army officers. -

Unquiet Graves Press Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Chas Moore 602.864.2356| [email protected] PHOENIX, Ariz. – (May 5, 2019) Western US Premiere of Unquiet Graves - film investigating collusion of the British Government with paramilitaries at the height of The Troubles in Northern Ireland Saturday June 8, 2019, 7PM Irish Cultural Center 1106 N. Central Ave. Phoenix, AZ 85004 The Irish Cultural Center and McClelland Library are excited to announce the Western United States Premiere of Unquiet Graves the latest film written and directed by award-winning Belfast filmmaker Seán Murray. Heartbreaking perspectives from the families of victims, chilling reconstructions, and a jaw- dropping interview with a whistleblower bring to the big screen the story of the Glenanne Gang and a sectarian killing spree that claimed the lives of over 120 innocent civilians during the 1970s. In painstaking detail, Murray details how members of the Northern Ireland police force and the largest British Army regiment, the Ulster Defense Regiment, was centrally involved in the murder of innocent people, the vast majority of them Catholic, in Counties Armagh and Tyrone and in the Irish Republic from 1972 - 1978. Among the victims of the Glenanne Gang are those murdered in the 1975 gun and bomb attack on the Miami Showband, now the subject of a major Netflix documentary, as well as 22-year-old Colm McCartney, a cousin of the late Nobel laureate, Seamus Heaney, for whom the famous poem ‘The Strand At Lough Beg’ was written. Based on Anne Cadwallader’s book, Lethal Allies and narrated by Oscar nominated actor Stephen Rae, this powerful film comes to Phoenix just weeks after the death of journalist Lyra McKee in Derry, a timely reminder of the complexities of Northern Ireland’s recent history and the fragility of its peace. -

Packet 14.Pdf

Pre-ICT and Nationals Open/Minnesota Open 2019 (PIANO/MO): “What about bad subject matter? Or a bad title drop, even? That could kill a tournament pretty good.” Written and edited by Jacob Reed, Adam Silverman, Sam Bailey, Michael Borecki, Stephen Eltinge, Adam S. Fine, Jason Golfinos, Matt Jackson, Wonyoung Jang, Michael Kearney, Moses Kitakule, Shan Kothari, Chloe Levine, John Marvin, and Derek So, with Joey Goldman and Will Holub-Moorman. Packet 14 Tossups 1. One of this economist’s theories was given empirical evidence in a paper by Costinot and Donaldson examining predicted agricultural productivity. A version of a model named for this economist uses an extreme value distribution of productivity to generate gravity equations. Eaton and Kortum built on earlier work by Dornbusch, Fischer, and Samuelson, who expanded this man’s model of two goods to cover a continuum of goods. Models named for this man typically focus on differences in (*) technology, rather than differences in factor endowments. He showed that, even if one agent is more productive in all tasks, there are still efficiency gains when multiple agents specialize. The “classic” version of his model of international trade is often contrasted with the Heckscher–Ohlin model. For 10 points, what economist used wine and cloth to exemplify the notion of comparative advantage? ANSWER: David Ricardo [accept answers including the adjective Ricardian] <SB> 2. Note to moderator: please read all of the sections in “quotes” slowly. A piece in this genre opens with the left hand outlining the bare fifth “C-sharp, G-sharp,” over which the right hand then plays a long E-natural, followed by repeated E-sharps. -

Newshound: Daily Northern Ireland News Catalog - Irish News Article

Newshound: Daily Northern Ireland news catalog - Irish News article Bleak reflection a cry for all north's victims HOME (Susan McKay, Irish News) History Mo Courtney walked free last week after Belfast Crown Court ruled he had no case to answer on a charge of NewsoftheIrish murdering young Alan 'Bucky' McCullough during a loyalist feud in 2003. Book Reviews Alex Maskey: Man and & Book Forum "You have to ask yourself if there is any justice in the world at all," the victim's mother, Barbara McCullough, whose Mayor by Barry McCaffrey Bookstore husband was also murdered in 1981, said. The family intends to appeal the ruling. This article appears Search / Archive Mrs McCullough expressed her sympathy for another thanks to the Irish News. Back to 10/96 bereaved mother, Vera McVeigh (82). Subscribe to the Irish News Papers Her teenage son, Columba, disappeared in 1975. She found out many years later that the IRA had abducted and murdered him and buried his body in a bog, where it still lies, Reference undiscovered, despite extensive searches. About On Thursday, the Reverend Ian Paisley visited Mrs McVeigh and appealed to those who knew where Columba's remains were to come forward. Contact Relatives of the six men murdered by the UVF in the Heights Bar at Loughinisland in 1994 went to Brussels to meet MEPs. They told the politicians they believed the RUC investigation had been compromised because of collusion between the killers and the security forces. Police Ombudsman Nuala O'Loan is investigating the handling of the case. It emerged that Mrs O'Loan's potentially explosive investigation of loyalist murders carried out by a north Belfast UVF gang will be delayed until early next year. -

Mcgurks Pub Bombing Physical Injury

APPLYING TO INVITATION THE MEMORIAL Towards Human Rights Join us at the Guildhall in Derry for a FUND and Truth Recovery The Memorial Fund is open to those ‘conversation with… Jesse Jackson’ who, as a result of the “Troubles” have lost family members, have themselves NEWSLETTER ISSUE 6/SPRING 2011 Jesse Jackson is a well known civil been injured, or are a registered pri- rights campaigner who marched with mary carer of an immediate family Martin Luther King. The PFC and the member who has an ongoing need for Bloody Sunday Trust are hosting a visit care as a result of a ‘Troubles’ related by Jesse Jackson to Derry. We would MCGURKS PUB BOMBING physical injury. like to invite all to attend “a conver- The Fund has a number of schemes sation with . Jesse Jackson” in the and while the amounts available are Victims vindicated th Guildhall on Sunday the 20 of March. small, many who are entitled to benefit Doors open at 3.30 and will close at may not be aware of the schemes. If you in PONI report – 3.55 sharp. Jesse Jackson will be talk- want more information or help making ing to Paul McFadden between 4pm an application give any of us a shout and retraumatised by and 5.30pm. Paul is well known as an we will be glad to help. experienced journalist and former BBC Chief Constable broadcaster. The UVF bomb on the night of Decem- ber 4th 1971 at McGurks Bar in North Belfast was an horrific and lasting trag- edy for all of those affected.