University of Copenhagen (Physics) in 1970

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Astrometry

5 Gaia web site: http://sci.esa.int/Gaia site: web Gaia 6 June 2009 June are emerging about the nature of our Galaxy. Galaxy. our of nature the about emerging are More detailed information can be found on the the on found be can information detailed More technologies developed by creative engineers. creative by developed technologies scientists all over the world, and important conclusions conclusions important and world, the over all scientists of the Universe combined with the most cutting-edge cutting-edge most the with combined Universe the of The results from Hipparcos are being analysed by by analysed being are Hipparcos from results The expression of a widespread curiosity about the nature nature the about curiosity widespread a of expression 118218 stars to a precision of around 1 milliarcsecond. milliarcsecond. 1 around of precision a to stars 118218 trying to answer for many centuries. It is the the is It centuries. many for answer to trying created with the positions, distances and motions of of motions and distances positions, the with created will bring light to questions that astronomers have been been have astronomers that questions to light bring will accuracies obtained from the ground. A catalogue was was catalogue A ground. the from obtained accuracies Gaia represents the dream of many generations as it it as generations many of dream the represents Gaia achieving an improvement of about 100 compared to to compared 100 about of improvement an achieving orbit, the Hipparcos satellite observed the whole sky, sky, whole the observed satellite Hipparcos the orbit, ear Y of them in the solar neighbourhood. -

The Astronomers Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler

Ice Core Records – From Volcanoes to Supernovas The Astronomers Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler Tycho Brahe (1546-1601, shown at left) was a nobleman from Denmark who made astronomy his life's work because he was so impressed when, as a boy, he saw an eclipse of the Sun take place at exactly the time it was predicted. Tycho's life's work in astronomy consisted of measuring the positions of the stars, planets, Moon, and Sun, every night and day possible, and carefully recording these measurements, year after year. Johannes Kepler (1571-1630, below right) came from a poor German family. He did not have it easy growing Tycho Brahe up. His father was a soldier, who was killed in a war, and his mother (who was once accused of witchcraft) did not treat him well. Kepler was taken out of school when he was a boy so that he could make money for the family by working as a waiter in an inn. As a young man Kepler studied theology and science, and discovered that he liked science better. He became an accomplished mathematician and a persistent and determined calculator. He was driven to find an explanation for order in the universe. He was convinced that the order of the planets and their movement through the sky could be explained through mathematical calculation and careful thinking. Johannes Kepler Tycho wanted to study science so that he could learn how to predict eclipses. He studied mathematics and astronomy in Germany. Then, in 1571, when he was 25, Tycho built his own observatory on an island (the King of Denmark gave him the island and some additional money just for that purpose). -

Galileo in Early Modern Denmark, 1600-1650

1 Galileo in early modern Denmark, 1600-1650 Helge Kragh Abstract: The scientific revolution in the first half of the seventeenth century, pioneered by figures such as Harvey, Galileo, Gassendi, Kepler and Descartes, was disseminated to the northernmost countries in Europe with considerable delay. In this essay I examine how and when Galileo’s new ideas in physics and astronomy became known in Denmark, and I compare the reception with the one in Sweden. It turns out that Galileo was almost exclusively known for his sensational use of the telescope to unravel the secrets of the heavens, meaning that he was predominantly seen as an astronomical innovator and advocate of the Copernican world system. Danish astronomy at the time was however based on Tycho Brahe’s view of the universe and therefore hostile to Copernican and, by implication, Galilean cosmology. Although Galileo’s telescope attracted much attention, it took about thirty years until a Danish astronomer actually used the instrument for observations. By the 1640s Galileo was generally admired for his astronomical discoveries, but no one in Denmark drew the consequence that the dogma of the central Earth, a fundamental feature of the Tychonian world picture, was therefore incorrect. 1. Introduction In the early 1940s the Swedish scholar Henrik Sandblad (1912-1992), later a professor of history of science and ideas at the University of Gothenburg, published a series of works in which he examined in detail the reception of Copernicanism in Sweden [Sandblad 1943; Sandblad 1944-1945]. Apart from a later summary account [Sandblad 1972], this investigation was published in Swedish and hence not accessible to most readers outside Scandinavia. -

Copernicus and Tycho Brahe

THE NEWTONIAN REVOLUTION – Part One Philosophy 167: Science Before Newton’s Principia Class 2 16th Century Astronomy: Copernicus and Tycho Brahe September 9, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. The Copernican Revolution .................................................................................................................. 1 A. Ptolemaic Astronomy: e.g. Longitudes of Mars ................................................................... 1 B. A Problem Raised for Philosophy of Science ....................................................................... 2 C. Background: 13 Centuries of Ptolemaic Astronomy ............................................................. 4 D. 15th Century Planetary Astronomy: Regiomantanus ............................................................. 5 E. Nicolaus Copernicus: A Brief Biography .............................................................................. 6 F. Copernicus and Ibn al-Shāţir (d. 1375) ……………………………………………………. 7 G. The Many Different Copernican Revolutions ........................................................................ 9 H. Some Comments on Kuhn’s View of Science ……………………………………………... 10 II. De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelstium (1543) ..................................................................................... 11 A. From Basic Ptolemaic to Basic Copernican ........................................................................... 11 B. A New Result: Relative Orbital Radii ................................................................................... 12 C. Orbital -

The Nova Stella and Its Observers

Running title: Nova stella 1572 AD The Nova Stella and its Observers P. Ruiz–Lapuente ∗,∗∗ 1. Introduction In 1572, physicists were still living with the concepts of mechanics inherited from Aris- totle and with the classification of the elements from the Greek philosopher. The growing criticism towards the Aristotelian views on the natural world could not turn very produc- tive, because the necessary elements of calculus and the empirical tools to move into a better frame were still lacking. However, in astronomy, observers had witnessed by that time the comet of 1556 and they would witness a new one in 1577. Moreover, since 1543 when De Revolutionibus Orbium Caelestium by Copernicus came to light, the apparent motion of the planets had a radically different explanation from the ortodox geocentrism. The new helio- centric view slowly won supporters among astronomers. The explanations concerning the planetary motions would depart from the “common sense” intuitions that had placed the earth sitting still at the center of the planetary system. Thus the “nova stella” in 1572 happened in the middle of the geocentric–versus–heliocentric debate. The other “nova”, the one that would be observed in 1604 by Kepler, came just shortly after the posthumous publication of Tycho Brahe’s Astronomiae Instauratae Progymnasmata1 which contains most of the debates in relation to the appearance of the “new star”2. arXiv:astro-ph/0502399v1 21 Feb 2005 The machinery moving the planetary spheres, i.e. the intrincate system of solid spheres rotating by the motion imparted to them as the wheels in a clock, was not directly affected by the new heliocentric proposal. -

Three Editions of the Star Catalogue of Tycho Brahe*

A&A 516, A28 (2010) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201014002 & c ESO 2010 Astrophysics Three editions of the star catalogue of Tycho Brahe Machine-readable versions and comparison with the modern Hipparcos Catalogue F. Verbunt1 andR.H.vanGent2,3 1 Astronomical Institute, Utrecht University, PO Box 80 000, 3508 TA Utrecht, The Netherlands e-mail: [email protected] 2 URU-Explokart, Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University, PO Box 80 115, 3508 TC Utrecht, The Netherlands 3 Institute for the History and Foundations of Science, PO Box 80 000, 3508 TA Utrecht, The Netherlands Received 6 January 2010 / Accepted 3 February 2010 ABSTRACT Tycho Brahe completed his catalogue with the positions and magnitudes of 1004 fixed stars in 1598. This catalogue circulated in manuscript form. Brahe edited a shorter version with 777 stars, printed in 1602, and Kepler edited the full catalogue of 1004 stars, printed in 1627. We provide machine-readable versions of the three versions of the catalogue, describe the differences between them and briefly discuss their accuracy on the basis of comparison with modern data from the Hipparcos Catalogue. We also compare our results with earlier analyses by Dreyer (1916, Tychonis Brahe Dani Scripta Astronomica, Vol. II) and Rawlins (1993, DIO, 3, 1), finding good overall agreement. The magnitudes given by Brahe correlate well with modern values, his longitudes and latitudes have error distributions with widths of 2, with excess numbers of stars with larger errors (as compared to Gaussian distributions), in particular for the faintest stars. Errors in positions larger than 10, which comprise about 15% of the entries, are likely due to computing or copying errors. -

History of Astronomy

NASE publications History of Astronomy History of Astronomy Jay Pasachoff, Magda Stavinschi, Mary Kay Hemenway International Astronomical Union, Williams College (Massachusetts, USA), Astronomical Institute of the Romanian Academy (Bucarest, Romania), University of Texas (Austin, USA) Summary This short survey of the History of Astronomy provides a brief overview of the ubiquitous nature of astronomy at its origins, followed by a summary of the key events in the development of astronomy in Western Europe to the time of Isaac Newton. Goals • Give a schematic overview of the history of astronomy in different areas throughout the world, in order to show that astronomy has always been of interest to all the people. • List the main figures in the history of astronomy who contributed to major changes in approaching this discipline up to Newton: Tycho Brahe, Copernicus, Kepler and Galileo. • Conference time constraints prevent us from developing the history of astronomy in our days, but more details can be found in other chapters of this book Pre-History With dark skies, ancient peoples could see the stars rise in the eastern part of the sky, move upward, and set in the west. In one direction, the stars moved in tiny circles. Today, when we look north, we see a star at that position – the North Star, or Polaris. It isn't a very bright star: 48 stars in the sky are brighter than it, but it happens to be in an interesting place. In ancient times, other stars were aligned with Earth's north pole, or sometimes, there were no stars in the vicinity of the pole. -

Copernicus, Tycho Brache, and Kepler

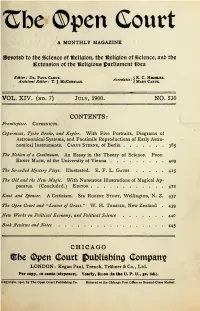

^be ©pen Gourt A MONTHLY MAGAZINE S)c\>otc& to tbc Science of "Religfon, tbe IRellgton of Science, an& tbe Bitension ot tbe IReliQious parliament f&ea EcHtor: Dr. Paul Caids. E- C. Hboblu. Astoaaus.j,.^^^t,..S -j Atnttant Editor: T. J. McCoemack. j^^^^^ Cards. VOL. XIV. (no. 7) July, 1900. NO. 530 CONTENTS: Frontispiece. Copernicus. Copernicus, Tycho Brake, and Kepler. With Five Portraits, Diagrams of Astronomical Systems, and Facsimile Reproductions of Early Astro- nomical Instruments. Carus Sterne, of Berlin 385 The Notion of a Continuum. An Essay in the Theory of Science. Prof. Ernst Mach, of the University of Vienna 409 The So-called Mystery Plays. Illustrated. E. F. L. Gauss 415 The Old and the New Magic. With Numerous Illustrations of Magical Ap- paratus. (Concluded.) Editor 422 Kant and Spencer. A Criticism. Sir Robert Stout, Wellington, N. Z. 437 The Open Court and ^'Leaves of Grass.'" W. H. Trimble, New Zealand . 439 New Works on Political Economy, and Political Science 440 Book Eeviews and Notes 445 CHICAGO ®be ©pen Court IpubUsbing Companie LONDON : Kegan Paul, Trench, Triibner & Co., Ltd. Per copy, 10 cents (sixpence). Yearly, $1.00 (In the U. P. U., 5s. 6(L). Copyright, 1900, by Tbe Open Court PvbliahiaK Co. Entered at the Chic«Ko Post Oflk;e as Second>Clasa MatUr. ^be ©pen Court A MONTHLY MAGAZINE 2)cvote& to tbe Science of IReligion, tbe IReUaton of Science, arH> tbe Extension ot tbe IReligious parliament irt)ea EcHtfr: Dr. Ca«us. E. C. Hboblxk. Paul Af*otMi€M.>#,,<,««/^, j j^^^^^ Atnsiant Editor: T. -

A True Demonstration Bellarmine and the Stars As Evidence Against Earth’S Motion in the Early Seventeenth Century

Christopher M. Graney A True Demonstration Bellarmine and the Stars as Evidence Against Earth’s Motion in the Early Seventeenth Century In 1615 Robert Cardinal Bellarmine demanded a “true demonstra- tion” of Earth’s motion before he would cease to doubt the Coperni- can world system. No such demonstration was available because the geocentric Tychonic world system was a viable alternative to the he- liocentric Copernican system. On the contrary, recent work concern- ing early observations of stars suggests that, thanks to astronomers’ misunderstanding of the images of stars seen through the telescope, the only “true demonstration” the telescope provided in Bellarmine’s day showed the earth not to circle the Sun. This had been discussed by the German astronomer Simon Marius, in his Mundus Iovialis, just prior to Bellarmine’s request for a “true demonstration.” In the early seventeenth century, careful telescopic observa- tions made by skilled astronomers did not support the heliocentric world system of Copernicus, but rather the geocentric world sys- tem of the great Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe. This was because early telescopic astronomers did not understand the limitations of their telescopes, which produced spurious views of stars. Since they failed to realize this, they concluded that the stars were not suffi- ciently distant to be compatible with the Copernican system.1 logos 14:3 summer 2011 70 logos In April 1615, in a letter offering his opinion on the Copernican world system, Robert Cardinal Bellarmine wrote: I say that if there were a true demonstration that the sun is at the center of the world and the earth in the third heaven, and that the sun does not circle the earth but the earth circles the sun, then one would have to proceed with great care in explaining the Scriptures that appear contrary, and say rather that we do not understand them then that what is demonstrated is false. -

Galileo Planetary Motion Tycho Brahe's Observations Kepler's Laws

Today Galileo Planetary Motion Tycho Brahe’s Observations Kepler’s Laws 1 Galileo c. 1564-1642 First telescopic astronomical2 observations • First use of telescope for astronomy in 1609 • 400 years ago! 3 Galileo’s observations of phases of Venus proved that it orbits the Sun and not Earth. 4 © 2007 Pearson Education Inc., publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley Phase and angular size Fig.of Venus 4.13 depend on elongation 5 Competing Cosmologies Geocentric Heliocentric Ptolemaic Copernican Earth at center Sun at center The sun is the source of light in both models Retrograde Motion Needs epicycles Consequence of Lapping nicer Inferiority of Mercury & Venus Must tie to sun Interior to Earth’s Orbit nicer Predicts - No parallax✓ - Parallax X - Venus: crescent phase only X - Venus: all phases6 ✓ © 2007 Pearson Education Inc., publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley Heliocentric Cosmology • Provides better explanation for – Retrograde motion – proximity of Mercury and Venus to the Sun • Provides only explanation for – Phases of Venus – Angular size variation of Venus • What about parallax? 7 © 2007 Pearson Education Inc., publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley How did Galileo solidify the Copernican revolution? Galileo (1564–1642) overcame major objections to the Copernican view. Three key objections rooted in the Aristotelian view were: 1. Earth could not be moving because objects in air would be left behind. 2. Noncircular orbits are not “perfect” as heavens should be. 3. If Earth were really orbiting Sun, we’d detect stellar parallax. 8 © 2007 Pearson Education Inc., publishing as Pearson Addison-Wesley Overcoming the first objection (nature of motion): Galileo’s experiments showed that objects in air would stay with a moving Earth. -

About Astronomy

About Astronomy Gazing up at the sky on a clear moonless night, you can see about two thousand stars. In the 2nd century B.C., Hipparchus, an ancient Greek astronomer, gazed at the sky and saw the same stars. Hipparchus spent years carefully observing the stars, and he became one of the first people to make a map of the sky. Using his map, together with observations made by the ancient Babylonians, he discovered that if you look at the positions of the stars on the first day of spring every year, they will have shifted slightly from the year before. His discovery ranks as one of the greatest discoveries in the history of astronomy. But he could not have made it without his map. Today, astronomers are on the verge of many other exciting discoveries. They have found objects called quasars, the size of the Solar System but brighter than an entire galaxy, that are the most distant objects in the universe. They have found faint failed stars called brown dwarfs, a missing link in the evolution of stars. And they are constructing a map of the entire universe that might shed light on the universe's origins fifteen billion years ago. But like Hipparchus, modern astronomers cannot continue to make these discoveries without an accurate map. Over the next few years, the Sloan Digital Sky Survey will make the most detailed map in the history of astronomy, a map that astronomers will use for decades to come. The History of Sky Surveys Sky surveys have had a long history, and have led to some of the most important discoveries in astronomy. -

Francesco Ingoli's Essay to Galileo: Tycho Brahe and Science in the Inquisition's Condemnation of the Copernican Theory

FRANCESCO INGOLI'S ESSAY TO GALILEO: TYCHO BRAHE AND SCIENCE IN THE INQUISITION'S CONDEMNATION OF THE COPERNICAN THEORY Christopher M. Graney Jefferson Community & Technical College 1000 Community College Drive Louisville, KY 40272 [email protected] In January of 1616, the month before before the Roman Inquisition would infamously condemn the Copernican theory as being “foolish and absurd in philosophy”, Monsignor Francesco Ingoli addressed Galileo Galilei with an essay entitled “Disputation concerning the location and rest of Earth against the system of Copernicus”. A rendition of this essay into English, along with the full text of the essay in the original Latin, is provided in this paper. The essay, upon which the Inquisition condemnation was likely based, lists mathematical, physical, and theological arguments against the Copernican theory. Ingoli asks Galileo to respond to those mathematical and physical arguments that are “more weighty”, and does not ask him to respond to the theological arguments at all. The mathematical and physical arguments Ingoli presents are largely the anti-Copernican arguments of the great Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe; one of these (an argument based on measurements of the apparent sizes of stars) was all but unanswerable. Ingoli's emphasis on the scientific arguments of Brahe, and his lack of emphasis on theological arguments, raises the question of whether the condemnation of the Copernican theory was, in contrast to how it is usually viewed, essentially scientific in nature, following the ideas of Brahe. Page 1 of 60 Page 2 of 60 “All have said, the said proposition to be foolish and absurd in philosophy; and formally heretical, since it expressly contradicts the meaning of sacred Scripture in many places according to the quality of the words and according to the common explanation and sense of the Holy Fathers and the doctors of theology.”1 -- statement regarding the Copernican theory from a committee of eleven consultants for the Roman Inquisition, 24 February 1616.