Steve Mackey's Music Has Muscle. It Behaves Like An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nasher Sculpture Center's Soundings Concert Honoring President John F. Kennedy with New Work by American Composer Steven Macke

Nasher Sculpture Center’s Soundings Concert Honoring President John F. Kennedy with New Work by American Composer Steven Mackey to be Performed at City Performance Hall; Guaranteed Seating with Soundings Season Ticket Package Brentano String Quartet Performance of One Red Rose, co-commissioned by the Nasher with Carnegie Hall and Yellow Barn, moved to accommodate bigger audience. DALLAS, Texas (September 12, 2013) – The Nasher Sculpture Center is pleased to announce that the JFK commemorative Soundings concert will be performed at City Performance Hall. Season tickets to Soundings are now on sale with guaranteed seating to the special concert honoring President Kennedy on the 50th anniversary of his death with an important new work by internationally renowned composer Steven Mackey. One Red Rose is written for the Brentano String Quartet in commemoration of this anniversary, and is commissioned by the Nasher (Dallas, TX) with Carnegie Hall (New York, NY) and Yellow Barn (Putney, VT). The concert will be held on Saturday, November 23, 2013 at 7:30 pm at City Performance Hall with celebrated musicians; the Brentano String Quartet, clarinetist Charles Neidich and pianist Seth Knopp. Mr. Mackey’s One Red Rose will be performed along with seminal works by Olivier Messiaen and John Cage. An encore performance of One Red Rose, will take place Sunday, November 24, 2013 at 2 pm at the Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza. Both concerts will include a discussion with the audience. Season tickets are now available at NasherSculptureCenter.org and individual tickets for the November 23 concert will be available for purchase on October 8, 2013. -

6 Program Notes

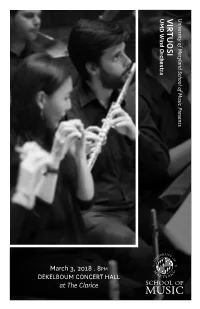

UMD Wind OrchestraUMD VIRTUOSI University Maryland of School Music of Presents March 3, 2018 . 8PM DEKELBOUM CONCERT HALL at The Clarice University of Maryland School of Music presents VIRTUOSI University of Maryland Wind Orchestra PROGRAM Michael Votta Jr., music director James Stern, violin Audrey Andrist, piano Kammerkonzert .........................................................................................................................Alban Berg I. Thema scherzoso con variazioni II. Adagio III. Rondo ritmico con introduzione James Stern, violin Audrey Andrist, piano INTERMISSION Serenade for Brass, Harp,Piano, ........................................................Willem van Otterloo Celesta, and Percussion I. Marsch II. Nocturne III. Scherzo IV. Hymne Danse Funambulesque .....................................................................................................Jules Strens I wander the world in a ..................................................................... Christopher Theofanidis dream of my own making 2 MICHAEL VOTTA, JR. has been hailed by critics as “a conductor with ABOUT THE ARTISTS the drive and ability to fully relay artistic thoughts” and praised for his “interpretations of definition, precision and most importantly, unmitigated joy.” Ensembles under his direction have received critical acclaim in the United States, Europe and Asia for their “exceptional spirit, verve and precision,” their “sterling examples of innovative programming” and “the kind of artistry that is often thought to be the exclusive -

Juilliard Orchestra Jeffrey Milarsky, Conductor Jaewon Wee, Violin

Thursday Evening, October 17, 2019, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard Orchestra Jeffrey Milarsky, Conductor Jaewon Wee, Violin ANNA THORVALDSDÓTTIR (b. 1977) Metacosmos (2018) SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891–1953) Violin Concerto No. 2 in G minor (1935) Allegro moderato Andante assai Allegro, ben marcato JAEWON WEE, Violin Intermission BÉLA BARTÓK (1881–1945) Concerto for Orchestra (1944) Introduzione. Andante non troppo—Allegro vivace Presentando le coppie. Allegro scherzando Elegia. Andante non troppo Intermezzo interrotto. Allegretto Finale. Presto Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 45 minutes, including an intermission The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. soundscapes is on full display in Notes on the Program Metacosmos. Unfolding as a single move- by Thomas May ment that lasts about 14 minutes, the piece manifests this composer’s aesthetic of deep Metacosmos listening as well as a contemporary slant on ANNA THORVALDSDÓTTIR Romantic concept of “organic” unity as the Born: July 11, 1977, in Reykjavik, Iceland basis for musical creativity. Thorvaldsdóttir describes her composition as “an ecosys- The Icelandic composer Anna Thorvaldsdóttir tem of materials that are carried from one emerged on the scene less than a decade performer—or performers—to the next ago (her debut album, Rhízo¯¯ma, appeared throughout the process of the work.” in 2011), but already she has become an internationally sought-after composer. -

Alan Shockley Kojiro Umezaki

dead, and a letter to a friend that he had written the previous year describing the passage of time in prison was later published. Rzewski read the letter, and set this excerpt. ABOUT KOJIRO UMEZAKI Born to a Japanese father and Danish mother, Kojiro Umezaki grew up in Tokyo and is a performer of the shakuhachi, a composer of electro-acoustic works, and a technologist with interests in developing portable and mobile interactive music systems for live performance. He performs regularly with the Grammy-nominated Silk Road Ensemble with whom he appears on the recordings Beyond the Horizon (Sony BMG, 2005), New Impossibilities (Sony BMG, 2007), Off the Map (World Village, 2009), NEW MUSIC and A Playlist Without Borders (Sony Masterworks, 2013). Other notable recordings of his work have been released on Brooklyn Rider's Dominant Curve (In A Circle, 2010); Yo-Yo Ma's Appassionato (Sony BMG, 2007) and Songs of Joy and Peace (Sony BMG, 2008); Beat in Fractions' Beat Infraction (Healthy Boys, 2007); and The Silk Road: A Musical Caravan (Smithsonian Folkways, 2002). Recent commissioned compositions and producer credits ENSEMBLE include those for Brooklyn Rider (2009), Joseph Gramley (2009, 2010), Huun Huur Tu (Ancestors Call, 2010), and the Silk Road Ensemble (2012). As Assistant Professor of Music at the University of California, Irvine, he is ALAN SHOCKLEY a core faculty member of the Integrated Composition, Improvisation, and Technology (ICIT) group where his research focuses on forms of hybrid music at the intersection of tradition and technology and intercultural DIRECTOR musical practices across the historic Silk Road regions and beyond. -

Concert: Chamber Music of Steven Mackey Steven Mackey

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 4-17-2011 Concert: Chamber Music of Steven Mackey Steven Mackey Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Mackey, Steven, "Concert: Chamber Music of Steven Mackey" (2011). All Concert & Recital Programs. 155. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/155 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Chamber Music of Steven Mackey The 2010-2011 Husa Visiting Professor of Composition Hockett Family Recital Hall Sunday, April 17, 2011 4:00 p.m. Indigenous Instruments Jacqueline Christen*, flute/piccolo Adam Butalewicz*, clarinet Kate Goldstein*, violin Nathan Gulla*, piano Richard Faria**, conductor Measures of Turbulence Eric Pearson, Matt Gillen, Nick Throop, Nick Malishak, Russ Knifin, guitar Dave Moore, Scott Card, electric guitar Sam Verneuille, electric bass Chun-Ming Chen, conductor Intermission Gaggle and Flock Gaggle Flock Nicholas DiEugenio**, Susan Waterbury**, Isaac Shiman, Sadie Kenny, violin Zachary Slack, Max Aleman, viola Elizabeth Simkin**, Peter Volpert, cello Jeffery Meyer**, conductor * Ithaca College Alumni ** Ithaca College Faculty Biography Steven Mackey Steven Mackey was born in 1956 to American parents stationed in Frankfurt, Germany. His first musical passion was playing the electric guitar, in rock bands based in northern California. He later discovered concert music and has composed for orchestras, chamber ensembles, dance, and opera. He regularly performs his own works, including two electric guitar concertos and numerous solo and chamber works, and is also active as an improvising musician and performs with his band Big Farm. -

Norfolk Chamber Music Festival Also Has an Generous and Committed Support of This Summer’S Season

Welcome To The Festival Welcome to another concerts that explore different aspects of this theme, I hope that season of “Music you come away intrigued, curious, and excited to learn and hear Among Friends” more. Professor Paul Berry returns to give his popular pre-concert at the Norfolk lectures, where he will add depth and context to the theme Chamber Music of the summer and also to the specific works on each Friday Festival. Norfolk is a evening concert. special place, where the beauty of the This summer we welcome violinist Martin Beaver, pianist Gilbert natural surroundings Kalish, and singer Janna Baty back to Norfolk. You will enjoy combines with the our resident ensemble the Brentano Quartet in the first two sounds of music to weeks of July, while the Miró Quartet returns for the last two create something truly weeks in July. Familiar returning artists include Ani Kavafian, magical. I’m pleased Melissa Reardon, Raman Ramakrishnan, David Shifrin, William that you are here Purvis, Allan Dean, Frank Morelli, and many others. Making to share in this their Norfolk debuts are pianist Wendy Chen and oboist special experience. James Austin Smith. In addition to I and the Faculty, Staff, and Fellows are most grateful to Dean the concerts that Blocker, the Yale School of Music, the Ellen Battell Stoeckel we put on every Trust, the donors, patrons, volunteers, and friends for their summer, the Norfolk Chamber Music Festival also has an generous and committed support of this summer’s season. educational component, in which we train the most promising Without the help of so many dedicated contributors, this festival instrumentalists from around the world in the art of chamber would not be possible. -

Eighth Blackbird Department of Music, University of Richmond

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Music Department Concert Programs Music 9-13-2004 Eighth Blackbird Department of Music, University of Richmond Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/all-music-programs Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Department of Music, University of Richmond, "Eighth Blackbird" (2004). Music Department Concert Programs. 351. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/all-music-programs/351 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Department Concert Programs by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Monday, September 13, 2004 • 7:30 pm Modlin Center for the Arts Camp Concert Hall, Booker Hall of Music ICM Artists, Ltd. presents eighth blackbird Molly Alicia Barth, flutes Michael J. Maccaferri, clarinets Matt Albert, violin Nicholas Photinos, cello Matthew L. Duvall, percussion Lisa Kaplan, piano Department ofMusic Ensemble-in-Residence Exclusive Management: ICM Artists, Ltd. 40 West 57th Street New York, New York 10019 David V. Foster, President and CEO Tonight's Program Critical Moments 2 (2001) GEORGE PERLE (b. 1915) Les Moutons des Panurge (1969) FREDERIC RZEWSKI (b. 1938) Indigenous Instruments (1989) STEVE MACKEY (b. 1956) -Intermission- Cendres (1998) KAIJA SMRIAHO (b. 1952) Dramamine (2002) DAVID M. GORDON (b. 1976) Molly Alicia Barth plays on a Lillian Burkart flute and piccolo A·b out t h e Art is t s eighth blackbird Molly Alicia Barth, flutes Michael J. Maccaferri, clarinets Matt Albert, violin & viola Nicholas Photinos, cello Matthew Duvall, percussion Lisa Kaplan, piano Hailed as ambassadors of new music, eighth blackbird has a growing reputation for its astounding musical versatility as well as its dedication to the works of today's composers. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1992

IS HiM Hi Tanglew®d Music Center Festival of Contemporary Music July 27 -August 2, 1992 G* Schirmer, Inc. and Associated Music Publishers, Inc. applaud John Harbison 1992 Composer- irvResidence i wp< wm Tanglewood Music Center Works available for sale Opera A Full Moon in March (1977) Vocal score, 50236490 Orchestra Concerto for Double Brass Choir and Orchestra (1988) Score, 50481513 Concerto for Piano (1978) Piano reduction, 50236210 The Merchant of Venice, Incidental Music (1971) for string orchestra Score, 50488508 Remembering Gatsby, Foxtrot for Orchestra (1985) Study Score, 50480538 Symphony No. 1 (1981) Study Score, 50480027 Chorus Ave Maria (1959) for women's chorus a cappella Score, 50481511 Five Songs of Experience (1971) for soloists, chorus, and ensemble Vocal score, 50231780 The Flight into Egypt, Sacred Ricercar (1986) for chorus and ensemble Vocal score, 50480255 He Shall Not Cry (1959) for women's chorus a cappella Score, 50481512 Music When Soft Voices Die (1975) for mixed chorus and harpsichord or organ Score, 50231750 Nunc Dimittis (1975) for men's chorus Score, 50233830 Chamber/Vocal/Solo Christmas Vespers (1988) for brass quintet and reader (in movement II) Score and parts, 50481660 Two Chorale Preludes for Advent (1987) The Three Wise Men (1988) Little Fantasy on "The Twelve Days of Christmas" (1988) Duo (1961) for flute and piano Score and part, 50488894 Fantasy Duo (1988) for violin and piano Score and part, 50481281 Mirabai Songs (1982) for soprano and ensemble Vocal score, 50480104 Mottetti di Montale (1980) for soprano and piano Vocal score, 50480303 Music for 18 Winds (1986) Score, 50488840 November 19, 1828 (1988) for piano quartet Score and parts, 50481406 Quintet for Winds (1979) Score and parts, 50481208 String Quartet No. -

PROGRAM NOTES 5 by Nicholas Alexander Brown

A Fine Centennial FRIDAY MAY 16, 2014 8:00 A Fine Centennial FRIDAY MAY 16, 2014 8:00 JORDAN HALL AT NEW ENGLAND CONSERVATORY Pre-concert talk with Nicholas Alexander Brown, Music Director & Founder, The Irving Fine Society – 7:00 IRVING FINE Blue Towers (1959) Remarks by Eric Chasalow, Irving G. Fine Professor of Music, Brandeis University and Emily and Claudia Fine IRVING FINE Diversions for Orchestra (1959) I. Little Toccata II. Flamingo Polka III. Koko’s Lullaby IV. The Red Queen’s Gavotte HAROLD SHAPERO Serenade in D for string orchestra (1945) I. Adagio—Allegro II. Menuetto (scherzando): Allegretto III. Larghetto, poco adagio IV. Intermezzo: Andantino con moto V. Finale: Allegro assai, poco presto INTERMISSION ARTHUR BERGER Prelude, Aria, and Waltz for string orchestra (1945, rev. 1982) I. Prelude II. Aria III. Waltz IRVING FINE Symphony (1962) I. Intrada: Andante quasi allegretto II. Capriccio: Allegro con spirito III. Ode: Grave GIL ROSE, Conductor Presented in collaboration with the Fine Family, The Irving Fine Society, and Brandeis University. PROGRAM NOTES 5 by Nicholas Alexander Brown This evening’s concert commemorates the Irving Fine centennial TINA TALLON with works by Fine and two of his most revered friends and colleagues, Harold Shapero and Arthur Berger. These three composers, along with Leonard Bernstein and Lukas Foss, are known collectively as the Boston School or Boston Group. Influenced greatly by Aaron TONIGHT’S PERFORMERS Copland, Serge Koussevitzky, Igor Stravinsky, and Nadia Boulanger (with whom several of them studied), these composers carved a place at the forefront of American music. Fine, Shapero, and Berger all spent time as students at at Harvard before making FLUTE TROMBONE VIOLIN II Brandeis University their musical home. -

A Program of Works by Guest Composer STEVEN MACKEY and by ANTHONY BRANDT PIERRE JALBERT KARLHEINZ STOCKHAUSEN

NEW MUSIC AT RICE A program of works by guest composer STEVEN MACKEY and by ANTHONY BRANDT PIERRE JALBERT KARLHEINZ STOCKHAUSEN Friday, February 5, 2010 8:00 p.m. Lillian H Duncan Recital Hall RICE UNIVERSITY PROGRAM String Trio (2008) Pierre Jalbert (b. 1967) Cho-Liang Lin, violin James Dunham, viola Norman Fischer, cello Focus (2010) Anthony Brandt Glow (b. 1961) Blur Flicker Dapple Embers Leone Buyse, flute Christian Slagle, percussion Michael Webster, clarinet Luke Hsu, violin Andrew Staupe, piano Rosanna Butterfield, cello Sadie Turner, harp Cristian Mdcelaru, conductor The Little Harlequin (1975) Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928-2007) Carlos Cordeiro, clarinet PAUSE Gaggle and Flock (2001) Steven Mackey Gaggle (b. 1956) Flock Quartet A Kaoru Suzuki (guest) and Terna Watstein, violins James Dunham, viola, Morgen Johnson, cello Quartet B David Huntsman and Tina Zhang, violins Roberto Papi, viola, Norman Fischer, cello The reverberative acoustics of Duncan Recital Hall magnify the slightest sound made by the audience. Your care and courtesy will be appreciated. The taking ofphotographs and use ofrecording equipment are prohibited. PROGRAM NOTES String Trio Pierre Jalbert My String Trio was commissioned by the South Bay Chamber Music Soci ety in Los Angeles for the Janaki String Trio, and was premiered there by the Janaki Trio in September 2008. The piece is in one movement and follows a conventional slow-fast-slow structure. The work begins very atmospherically, with a slow, lyrical melody introduced by the cello. This quickly gives way to a faster, more aggressive section ofmusic where a rapid, repeated note figure, played with a jete - bouncing bow technique, is taken up by each player. -

Juilliard Orchestra Jeffrey Milarsky , Conductor Brenden Zak , Violin

Thursday Evening, November 8, 2018, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard Orchestra Jeffrey Milarsky , Conductor Brenden Zak , Violin AUGUSTA READ THOMAS (b. 1964) Prayer Bells LEONARD BERNSTEIN (1918 –90) Serenade (After Plato’s “Symposium”) Phaedras - Pausanias: Lento - Allegro Aristophanes: Allegretto Eryximachus: Presto Agathon: Adagio Socrates - Alcibiades: Molto tenuto - Allegro molto BRENDEN ZAK , Violin Intermission SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891 –1953) Suite from Romeo and Juliet Montagues and Capulets The Young Juliet Romeo and Juliet Before Parting Romeo at Juliet’s Tomb Masks Balcony Scene Death of Tybalt Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 45 minutes, including one intermission The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Notes on the Program Thomas composed Prayer Bells in 2001 on commission from the Pittsburgh Symphony by James M. Keller Orchestra and its conductor, Mariss Jansons, who presented its premiere on May 4 of Prayer Bells that year. She provided this comment AUGUSTA READ THOMAS about the piece: Born April 24, 1964, in Glen Cove, New York Currently residing in Chicago There is an indisputable journey taking place during the 12-minute composition. Augusta Read Thomas, who began com - In general the score falls into a three-part posing as a child, has become one of the form: a slow-growing introduction of 90 most admired and fêted of her generation seconds (which is a section of music I of American composers. -

Juilliard Orchestra DAVID ROBERTSON, Conductor STEPHEN KIM, Violin

Tuesday Evening, February 25, 2020, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium / Ronald O. Perelman Stage THE JUILLIARD SCHOOL presents Juilliard Orchestra DAVID ROBERTSON, Conductor STEPHEN KIM, Violin STEVEN MACKEY Beautiful Passing (2008) (b. 1956) STEPHEN KIM, Violin Intermission GUSTAV MAHLER Symphony No. 5 in C-sharp minor (1901–02) (1860–1911) Erster Teil 1. Trauermarsch: in gemessenem Schritt, Streng, Wie ein Kondukt 2. Stürmisch bewegt, mit grösster Vehemenz Zweiter Teil 3. Scherzo: Kräftig, nicht zu schnell Dritter Teil 4. Adagietto: Sehr langsam 5. Rondo-Finale: Allegro Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 50 minutes, including an intermission This performance is made possible with support from the Celia Ascher Fund for Juilliard. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. Notes ON THE PROGRAM by James M. Keller Beautiful Passing STEVEN MACKEY Born February 14, 1956, in Frankfurt, Germany Lives in Princeton, New Jersey Growing up in northern California, percussion is managed by a timpanist Steven Mackey engaged in a favorite and two other players; they sometimes activity of male teenagers—playing employ special techniques, like bowing electric guitar in rock bands. His gongs and cymbals or dropping tennis awareness of “concert music” developed balls onto the head of a kettledrum. a bit later, in the course of studies at the University of California, Davis; Although Mackey principally composes State University of New York at Stony for instrumental ensembles, his Brook; and Brandeis University (from catalogue also includes several vocal which he holds a Ph.D.). Since 1985 he and stage works. One of them, the has taught at Princeton University, and multidisciplinary Slide (2009), for actor/ in 1991 he was awarded that school’s singer, electric guitar, and instrumental first-ever distinguished teaching award.