The Character of Future Conflicts — Partial Report 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OCTOBER 4, 2018 the INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER of the UNIVERSITY of IOWA COMMUNITY SINCE 1868 DAILYIOWAN.COM 50¢ INSIDE 80 Hours

The Daily Iowan THURSDAY, OCTOBER 4, 2018 THE INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA COMMUNITY SINCE 1868 DAILYIOWAN.COM 50¢ INSIDE 80 Hours The weekend in arts & entertainment Thursday, October 4, 2018 IC police make arrest in weekend shooting The Art of the SCREAM An Iowa City woman has been charged in connection with the Sept. 29 shooting at Court and Gilbert Streets. BY CHARLES PECKMAN reckless use of a firearm. Once officers arrived, a male victim was wound. The second male victim’s in- [email protected] According to a press release from discovered suffering from an apparent juries were also non-life-threatening, the city of Iowa City, the investigation gunshot wound. The injuries sustained and he was also transported to UIHC. Iowa City police have made an arrest is ongoing by the Iowa City Police De- by the victim were non-life-threatening, As The Daily Iowan has previously on Wednesday in connection to a shoot- partment’s Investigations Division. and he was transported to the University reported, Sgt. Jerry Blomgren said in- ing that happened on Sept. 29 near East The press release encourages anyone of Iowa Hospital. dividuals at the scene, including those Court and South Gilbert Streets. with information to contact the police. Shortly after the first victim was who were shot, did not cooperate with Arielle Grier, 24, of Iowa City has On Sept. 29, Iowa City police received a discovered, a second person was locat- authorities. Blomgren said Sept. 29 that been charged with two counts of at- report of shots fired near the intersection ed one block away from the shooting’s authorities planned to use surveillance tempted murder and one count of of East Court and South Gilbert Streets. -

Introduction ROBERT AUNGER a Number of Prominent Academics

CHAPTER 1: Introduction ROBERT AUNGER A number of prominent academics have recently argued that we are entering a period in which evolutionary theory is being applied to every conceivable domain of inquiry. Witness the development of fields such as evolutionary ecology (Krebs and Davies 1997), evolutionary economics (Nelson and Winter 1982), evolutionary psychology (Barkow et al. 1992), evolutionary linguistics (Pinker 1994) and literary theory (Carroll 1995), evolutionary epistemology (Callebaut and Pinxten 1987), evolutionary computational science (Koza 1992), evolutionary medicine (Nesse and Williams 1994) and psychiatry (McGuire and Troisi 1998) -- even evolutionary chemistry (Wilson and Czarnik 1997) and evolutionary physics (Smolin 1997). Such developments certainly suggest that Darwin’s legacy continues to grow. The new millennium can therefore be called the Age of Universal Darwinism (Dennett 1995; Cziko 1995). What unifies these approaches? Dan Dennett (1995) has argued that Darwin’s “dangerous idea” is an abstract algorithm, often called the “replicator dynamic.” This dynamic consists of repeated iterations of selection from among randomly mutating replicators. Replicators, in turn, are units of information with the ability to reproduce themselves using resources from some material substrate. Couched in these terms, the evolutionary process is obviously quite general. for example, the replicator dynamic, when played out on biological material such as DNA, is called natural selection. But Dennett suggests there are essentially no limits to the phenomena which can be treated using this algorithm, although there will be variation in the degree to which such treatment leads to productive insights. The primary hold-out from “evolutionarization,” it seems, is the social sciences. Twenty-five years have now passed since the biologist Richard Dawkins introduced the notion of a meme, or an idea that becomes commonly shared through social transmission, into the scholastic lexicon. -

The Role of the Online News Media in Reporting ISIS Terrorist Attacks In

The Role of the Online News Media in Reporting ISIS Terrorist Attacks in Europe (2014-present): the Case of BBC Online Agne Vaitekenaite A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Master of Arts in International Journalism COMM5600 Dissertation and Research Methods School of Media and Communication University of Leeds 29 August 2018 Word count: 14,955 ABSTRACT The numbers of ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) terrorist attacks have risen in Europe since 2014. Consequently, these incidents have particularly attracted the media attention and received a great amount of news coverage. The study has examined the role of that the online news media in reporting ISIS terrorist attacks during the period between 2014-present, based on the fact, that the online news has overtaken the print media and the television as the most popular source of the news within the last few years (Newman et al., 2018). Hence, this allows it to reach and affect the highest numbers of audience. The research has focused on the case study of the British Broadcasting Corporation news website BBC Online coverage on the Manchester Arena bombing, which was caused by ISIS. The study has investigated the news coverage throughout 29 weeks since the date of the terrorist attack, what includes the period between the 22nd May 2017 and the 11th December 2017. This time slot has provided the qualitative study with 155 articles, what were analysed while conducting the thematic analysis. The findings indicated that some themes are dominant in the content of the online news media coverage on ISIS terrorist attacks. -

Radio Essentials 2012

Artist Song Series Issue Track 44 When Your Heart Stops BeatingHitz Radio Issue 81 14 112 Dance With Me Hitz Radio Issue 19 12 112 Peaches & Cream Hitz Radio Issue 13 11 311 Don't Tread On Me Hitz Radio Issue 64 8 311 Love Song Hitz Radio Issue 48 5 - Happy Birthday To You Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 21 - Wedding Processional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 22 - Wedding Recessional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 23 10 Years Beautiful Hitz Radio Issue 99 6 10 Years Burnout Modern Rock RadioJul-18 10 10 Years Wasteland Hitz Radio Issue 68 4 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night Radio Essential IssueSeries 44 Disc 44 4 1975, The Chocolate Modern Rock RadioDec-13 12 1975, The Girls Mainstream RadioNov-14 8 1975, The Give Yourself A Try Modern Rock RadioSep-18 20 1975, The Love It If We Made It Modern Rock RadioJan-19 16 1975, The Love Me Modern Rock RadioJan-16 10 1975, The Sex Modern Rock RadioMar-14 18 1975, The Somebody Else Modern Rock RadioOct-16 21 1975, The The City Modern Rock RadioFeb-14 12 1975, The The Sound Modern Rock RadioJun-16 10 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 4 2 Pistols She Got It Hitz Radio Issue 96 16 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This Radio Essential IssueSeries 23 Disc 23 3 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 16 21 Savage Feat. J. Cole a lot Mainstream RadioMay-19 11 3 Deep Can't Get Over You Hitz Radio Issue 16 6 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Hitz Radio Issue 46 6 3 Doors Down Be Like That Hitz Radio Issue 16 2 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Hitz Radio Issue 62 16 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Hitz Radio Issue 12 15 3 Doors Down Here Without You Hitz Radio Issue 41 14 3 Doors Down In The Dark Modern Rock RadioMar-16 10 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time Hitz Radio Issue 95 3 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Hitz Radio Issue 3 9 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Hitz Radio Issue 57 15 3 Doors Down One Light Modern Rock RadioJan-13 6 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Hitz Radio Issue 31 2 3 Doors Down Feat. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

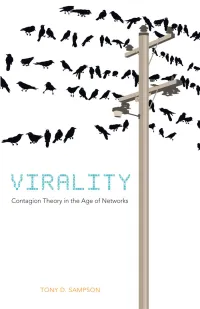

Virality : Contagion Theory in the Age of Networks / Tony D

VIRALITY This page intentionally left blank VIRALITY TONY D. SAMPSON UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA PRESS Minneapolis London Portions of chapters 1 and 3 were previously published as “Error-Contagion: Network Hypnosis and Collective Culpability,” in Error: Glitch, Noise, and Jam in New Media Cultures, ed. Mark Nunes (New York: Continuum, 2011). Portions of chapters 4 and 5 were previously published as “Contagion Theory beyond the Microbe,” in C Theory: Journal of Theory, Technology, and Culture (January 2011), http://www.ctheory.net/articles.aspx?id=675. Copyright 2012 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 http://www.upress.umn.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sampson, Tony D. Virality : contagion theory in the age of networks / Tony D. Sampson. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8166-7004-8 (hc : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8166-7005-5 (pb : alk. paper) 1. Imitation. 2. Social interaction. 3. Crowds. 4. Tarde, Gabriel, 1843–1904. I. Title. BF357.S26 2012 302'.41—dc23 2012008201 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer. 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Dedicated to John Stanley Sampson (1960–1984) This page intentionally left blank Contents Introduction 1 1. -

The Histories and Origins of Memetics

Betwixt the Popular and Academic: The Histories and Origins of Memetics Brent K. Jesiek Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Science and Technology Studies Gary L. Downey (Chair) Megan Boler Barbara Reeves May 20, 2003 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: discipline formation, history, meme, memetics, origin stories, popularization Copyright 2003, Brent K. Jesiek Betwixt the Popular and Academic: The Histories and Origins of Memetics Brent K. Jesiek Abstract In this thesis I develop a contemporary history of memetics, or the field dedicated to the study of memes. Those working in the realm of meme theory have been generally concerned with developing either evolutionary or epidemiological approaches to the study of human culture, with memes viewed as discrete units of cultural transmission. At the center of my account is the argument that memetics has been characterized by an atypical pattern of growth, with the meme concept only moving toward greater academic legitimacy after significant development and diffusion in the popular realm. As revealed by my analysis, the history of memetics upends conventional understandings of discipline formation and the popularization of scientific ideas, making it a novel and informative case study in the realm of science and technology studies. Furthermore, this project underscores how the development of fields and disciplines is thoroughly intertwined with a larger social, cultural, and historical milieu. Acknowledgments I would like to take this opportunity to thank my family, friends, and colleagues for their invaluable encouragement and assistance as I worked on this project. -

OF CHRISTMAS by Hannah Craven

MEET THE TEAM George McMillan Editor-in-Chief [email protected] Congratulations on making it through the first semester of this uni year, I hope you’ve enjoyed these past three months. Here at Nerve we’ve been working hard round the clock to showcase some of the talented writers we have here at the university. In issue #3 of the mag we bring you interviews with DMA’s and Lewis Capaldi, some great features on the upcoming festive season and our big review of the year. Have a great couple weeks off, enjoy your Christmas and we’ll see you in the new year! Ryan Evans Aakash Bhatia Zlatna Nedev Design & Deputy Editor Features Editor Fashion & Lifestyle Editor [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Silva Chege Claire Boad Jonathan Nagioff Debates Editor Entertainment Editor Sports Editor [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 3 @nervemagazinebu CONTENTS /Nerve Now 60 DMA’s Photo credit: Sven Mandel on Wikimedia Commons 88 DARTS WORLD 6 CHAMPIONSHIP BIG REVIEW 2018 4 Powered by ISSUE 3 | DECEMBER 2018 | CHRISTMAS EDITION BIG REVIEW 6 FEATURES 16 Commercialisation at Christmas 17 Christmas in Scandinavia 20 CONTRIBUTORS Help for the Homeless 22 FEATURES Crohn’s and Colitis Awareness Week 24 Hannah Craven Jake Carter FASHION & LIFESTYLE 26 Charlotte Willis Secret Santa Ideas 27 Ryan Evans Fashion on Campus 30 Best places to visit at Christmas 34 FASHION & LIFESTYLE Clare Stephenson Christmas Traditions across the World 36 Raluca Rusoiu Party season outfit Inspiration -

Contagion: Historical and Cultural Studies / Edited by Alison 7 Bashford and Claire Hooker

1111 2 Contagion 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1011 1 2 3111 In the age of HIV, antibiotic-resistant bacteria, the Ebola virus and BSE, 4 the metaphors and experience of contagion are a central concern of govern- 5 ment, biomedicine and popular culture. 6 Contagion explores cultural responses to infectious diseases and their 7 biomedical management over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It 8 also investigates the use of ‘contagion’ as a concept in postmodern re- 9 thinking of embodied subjectivity. 20111 These essays are written from within the fields of cultural studies, 1 biomedical history and critical sociology. The contributors examine 2 the geographies, policies and identities which have been produced in the 3 massive social effort to contain diseases. They explore both social responses 4 to infectious diseases in the past, and contemporary theoretical and biomed- 5 ical sites for the study of contagion. 6 7 Alison Bashford is Chair of the Department of Gender Studies at the 8 University of Sydney. She writes on the cultural history of medicine in 9 the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In 1998 she published Purity and 30111 Pollution: Gender, Embodiment and Victorian Medicine (St Martin’s Press/ 1 Macmillan) and is currently completing Public Health and the Imagining of 2 Australia, 1880–1940. 3 4 Claire Hooker is a research associate with the History and Material 5 Culture of Public Health in Australia Project, Department of Gender 6 Studies, University of Sydney, in collaboration with the Powerhouse 7 Museum, Sydney. Her book Not a Job in the Ordinary Sense: Women and Science 8 in Australia is forthcoming (Melbourne University Press). -

Muse Simulation Theory Deluxe Edition Mp3 Free Download Mega

muse simulation theory deluxe edition mp3 free download mega Simulation Theory by Muse (CD, 2018) С самой низкой ценой, совершенно новый, неиспользованный, неоткрытый, неповрежденный товар в оригинальной упаковке (если товар поставляется в упаковке). Упаковка должна быть такой же, как упаковка этого товара в розничных магазинах, за исключением тех случаев, когда товар является изделием ручной работы или был упакован производителем в упаковку не для розничной продажи, например в коробку без маркировки или в пластиковый пакет. См. подробные сведения с дополнительным описанием товара. Muse Simulation Theory. One of the most popular band on Has it Leaked has a new album on the way. Right now, it's very likely the album title is "Simulation Theory", with "Emotionality Rush" also being discussed. Reddit member diegopc5 dug out the info, compiling a pretty solid argument that Simulation Theory is in fact the title. And it sure is a very Muse-ish title. Video. Something Human Teaser. MUSE - Something Human [Official Music Video] The Dark Side. Track list (Standard Edition): 01. Algorithm 02. The Dark Side 03. Pressure 04. Propaganda 05. Break It To Me 06. Something Human 07. Thought Contagion 08. Get Up and Fight 09. Blockades 10. Dig Down 11. The Void. Track list (Deluxe Edition): 01. Algorithm 02. The Dark Side 03. Pressure 04. Propaganda 05. Break It To Me 06. Something Human 07. Thought Contagion 08. Get Up and Fight 09. Blockades 10. Dig Down 11. The Void 12. Algorithm (Alternate Reality Version) 13. The Dark Side (Alternate Reality Version) 14. Propaganda (Acoustic) 15. Something Human (Acoustic) 16. Dig Down (Acoustic Gospel Version) Muse - Pressure. -

Muse Gir Deg Nytt, Fremtidsrettet Album

Muse (c) Jeff Forney 09-11-2018 09:00 CET Muse gir deg nytt, fremtidsrettet album Muse utgir deres åttende studioalbum Simulation Theory via Warner Bros i dag. Albumet har totalt 11 spor og er produsert av bandet selv, sammen med flere prisvinnende produsenter som Rich Costey, Mike Elizondo, Shellback og Timbaland. Tidligere i høst slapp trioen noen smakebiter i form av singlene «Pressure / The Dark Side / Something Human / Thought Contagion / Dig Down» med hver sin tilhørende musikkvideo. Bandet har gjennom årene skapt en umiddelbart gjenkjennelig sound bestående av Matt Bellamy’s karakteristiske, svevende vokal og forrykende gitar, samt de drivende rytmepartiene ved Chris Wolstenholme og Dominic Howard. Denne stadion-rungende merkevaren er også høyst tilstedeværende på de siste singlene, hvilket ser ut til å ha falt i smak med strømmetall på over 7,5 millioner på «The Dark Side» og over 6,5 millioner på «Pressure» på Spotify. Den tilhørende musikkvideoen til førstnevnte har dessuten også nesten 7 millioner visninger på YouTube. Simulation Theoryblir utgitt i tre ulike formater: standard (11 låter), deluxe (16 låter), og super deluxe (21 låter). Den utvidede låtlisten består av en akustisk versjon av «Dig Down», samarbeid med the UCLA Bruin Marching Band på «Pressure», en live-versjon av «Thought Contagion», samt akustiske versjoner av flere låter inkludert «Something Human», «Alternate Reality», «Algorithm» og «The Dark Side». For detaljert liste over låtene i hvert format, se nederst. Albumcoveret er illustrert av den digitale artisten Kyle Lambert som står bak poster illustrasjoner for Stranger Things, Jurassic Park, og mange flere filmer. Simulation Theory blir etterfølgeren til Drones fra 2015 som debuterte som No.1 i 21 land rundt omkring i verden, i tillegg til å sikre bandet deres andre Grammy for Best Rock Album. -

Cultural Replication Theory and Law: Proximate Mechanisms Make a Difference

CULTURAL REPLICATION THEORY AND LAW: PROXIMATE MECHANISMS MAKE A DIFFERENCE Oliver R. Goodenough* INTRODUCTION Does law itself evolve? It has been widely suggested that culturally transmitted-behavioral information exhibits a Darwinian evolutionary dynamic.1 The argument is straightforward. Darwinian evolution has three basic elements: (1) replicative descent with (2) variation, subject to (3) a form of selection.2 Bundles of cultural information as diverse as language, * Professor, Vermont Law School; J.D. 1978, University of Pennsylvania; B.A. 1975 Harvard University. 1. See, e.g., SUSAN BLACKMORE, THE MEME MACHINE 9 (1999) (“[M]any aspects of human nature are explained far better by a theory of memetics than by any rival theory yet available.”); ROBERT BOYD & PETER J. RICHERSON, CULTURE AND THE EVOLUTIONARY PROCESS 2 (1985) (proposing a “dual inheritance theory” by linking “models of cultural transmission to models of genetic evolution”); L.L. CAVALLI-SFORZA & M.W. FELDMAN, CULTURAL TRANSMISSION AND EVOLUTION: A QUANTITATIVE APPROACH 362–66 (1981) (discussing an example of “how a cultural adaptation, and hence culture itself, can promote Darwinian fitness of a species”); RICHARD DAWKINS, THE SELFISH GENE 1 (2d ed. 1989) (exploring the consequences of Darwinian evolutionary theory in order “to examine the biology of selfishness and altruism”); PETER J. RICHERSON & ROBERT BOYD, NOT BY GENES ALONE: HOW CULTURE TRANSFORMED HUMAN EVOLUTION 3–4 (2005) (arguing that culture and human biology are intimately intertwined); Robert Aunger, Introduction to DARWINIZING CULTURE: THE STATUS OF MEMETICS AS A SCIENCE 1, 1 (Robert Aunger ed., 2000) (examining the roles of memes in the social sciences generally); William H.