Blasphemy in Inferno

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNITED ARAB EMIRATES UNITED ARAB EMIRATES RELIGIONS 1.1% 1.9% Agnostics Buddhists 1.3% Other 11.0% Christians 6.2% Hindus

Religious Freedom in the World Report 2021 UNITED ARAB EMIRATES UNITED ARAB EMIRATES RELIGIONS 1.1% 1.9% Agnostics Buddhists 1.3% Other 11.0% Christians 6.2% Hindus Population Area 9,813,170 83,600 Km2 78.5% GDP per capita GINI INDEX* Muslims 67,293 US$ 32.5 *Economic Inequality tion of committing adultery.”2 Article 1 of the penal code LEGAL FRAMEWORK ON FREEDOM OF RELIGION provides that Islamic law applies in hudud cases, including AND ACTUAL APPLICATION the payment of blood money in cases of murder. Article 66 states that the “original punishments” under the law apply to hudud crimes, including the death penalty. No one, The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is a federation of seven however, has been prosecuted or punished by a court for emirates situated in the Persian Gulf. Dubai is politically such an offence. and economically the most important of them. The law criminalises blasphemy and imposes fines and According to the constitution of 1971,1 Islam is the official imprisonment in these cases. Insulting other religions is religion of the federation. Article 7 reads: “Islam is the of- also banned. Non-citizens face deportation in case of ficial religion of the UAE. Islamic Shari‘a is a main source blasphemy. of legislation in the UAE.” Article 25 excludes discrimina- tion based on religion. It states: “All persons are equal in While Muslims may proselytise, penalties are in place for law. There shall be no distinction among the citizens of the non-Muslims doing the same among Muslims. If caught, UAE on the basis of race, nationality, faith or social status.” non-citizens may have their residency revoked and face Article 32 states: “Freedom to exercise religious worship deportation. -

BLASPHEMY LAWS in the 21ST CENTURY: a VIOLATION of HUMAN RIGHTS in PAKISTAN Fanny Mazna Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School 2017 BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY: A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN Fanny Mazna Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Mazna, Fanny. "BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY: A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN." (Jan 2017). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN by Fanny Mazna B.A., Kinnaird College for Women, 2014 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Department of Mass Communication and Media Arts in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2017 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN By Fanny Mazna A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the field of Mass Communication and Media Arts Approved by: William Babcock, Co-Chair William Freivogel, Co-Chair Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April, 6th 2017 AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF FANNY MAZNA, for the Master of Science degree in MASS COMMUNICATION AND MEDIA ARTS presented on APRIL, 6th 2017, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: BLASPHEMY LAWS IN THE 21ST CENTURY- A VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN PAKISTAN MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. -

Malta Is a Small, Densely-Populated Island Nation of 450,000 Inhabitants, Located in the Mediterranean Sea, South of Sicily

Malta Malta is a small, densely-populated island nation of 450,000 inhabitants, located in the Mediterranean Sea, south of Sicily. It is a parliamentary republic and member state of the European Union. Despite opposition from the Catholic Church, which remains hugely influential, Malta has seen significant progressive reforms in recent years including the introduction of divorce and same-sex civil unions, and the abolition of the country’s “blasphemy” law. Constitution and Education and Family, Freedom of government children’s rights community, expression society, religious advocacy of courts and humanist values tribunals There is There is state Discriminatory systematic funding of at least prominence is religious privilege some religious given to religious Preferential schools bodies, traditions treatment is given Religious schools or leaders to a religion or have powers to Religious groups religion in general discriminate in control some There is an admissions or public or social established employment services church or state religion State-funding of religious institutions or salaries, or discriminatory tax exemptions Constitution and Education and Family, Freedom of government children’s rights community, expression society, religious advocacy of courts and humanist values tribunals Official symbolic Concerns that deference to secular or religion religious authorities interfere in specifically religious freedoms Legend Constitution and government Freedom of conscience, religion, and expression are protected in law (Articles 40 and 41, Constitution of Malta). However, in practice, strong preference is afforded to the Roman Catholic Church, and Catholicism remains the official state religion of Malta (Article 2). Education and children’s rights The constitution prescribes religious teaching of the Catholic faith as compulsory education in all State schools: Article 2: (1) The religion of Malta is the Roman Catholic Apostolic Religion. -

Blasphemy, Charlie Hebdo, and the Freedom of Belief and Expression

Blasphemy, Charlie Hebdo, and the Freedom of Belief and Expression The Paris attacks and the reactions rashad ali The horrific events in Paris, with the killing of a group of Other reactions highlight and emphasise the fact journalists, a Police officer, and members of the Jewish that Muslims are also victims of terrorism – often the community in France have shocked and horrified most main victims – a point which Charlie Hebdo made in commentators. These atrocities, which the Yemen branch an editorial of the first issue of the magazine published of the global terrorist group al-Qaeda have claimed the following the attack on its staff. Still others highlight responsibility for,1 have led to condemnations from that Jews were targeted merely because they were Jews.2 across the political spectrum and across religious divides. This was even more relevant given how a BBC journalist Some ubiquitous slogans that have arisen, whether appeared to suggest that there was a connection between Je suis Charlie, Ahmed, or Juif, have been used to show how “Jews” treated Palestinians in Israel and the killing of empathy with various victims of these horrid events. Jews in France in a kosher shop.3 These different responses illustrate some of the divides in The most notorious response arguably has not come public reaction, with solidarity shown to various camps. from Islamist circles but from the French neo-fascist For example, some have wished to show support and comedian Dieudonne for stating on his Facebook solidarity with the victims but have not wished to imply account “je me sens Charlie Coulibaly” (“I feel like Charlie or show support to Charlie Hebdo as a publication, Coulibaly”). -

"Blasphemy"? Jesus Before Caiaphas in Mark 14:61-64

CHAPTER ELEVEN IN WHAT SENSE "BLASPHEMY"? JESUS BEFORE CAIAPHAS IN MARK 14:61-64 Jesus' response to the question of Caiaphas, in which he affirms that he is "the Christ the Son of the Blessed," whom Caiaphas and company "will see" as "Son of Man seated at the right hand of Power and coming with the clouds of heaven" (Mark 14:61-62), provokes the cry of "blasphemy!" (Mark 14:64). Many scholars have wondered why, and for good reason. Claiming to be Israel's Messiah was not considered blasphemous.! Although disparaging them as impostors and opportun ists, Josephus never accused any of the many would-be kings and deliverers of first-century Israel as blasphemers. Perhaps a more telling example comes from rabbinic tradition. Rabbi Aqiba's procla mation of Simon ben Kosiba as Messiah was met with skepticism, but not with cries of blasphemy (cf. y. Ta'an. 4.5; b. Sanh. 93b.) Even W. L. Lane (The Gospel of Mark [NIC; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1974] 536) argues that "anyone who [was in prison and deserted by his followers, but nevertheless still] proclaimed himself to be the Messiah could not fail to be a blasphemer who dared to make a mockery of the promises given by God to his people." This is no more than an assumption. There is no evidence that a claim to be Messiah, under any circumstances, was considered blasphemous (pace J. C. O'Neill, "The Silence of Jesus," NTS 15 [1969] 153-67; idem, "The Charge of Blasphemy at Jesus' Trial before the Sanhedrin," in E. -

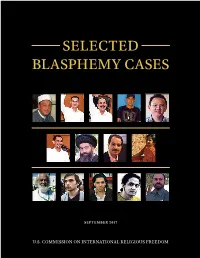

Selected Blasphemy Cases

SELECTED BLASPHEMY CASES SEPTEMBER 2017 U.S. COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Mohamed Basuki “Ahok” Abdullah al-Nasr Andry Cahya Ahmed Musadeq Sebastian Joe Tjahaja Purnama EGYPT INDONESIA INDONESIA INDONESIA INDONESIA Ayatollah Mohammad Mahful Muis Kazemeini Mohammad Tumanurung Boroujerdi Ali Taheri Aasia Bibi INDONESIA IRAN IRAN PAKISTAN Ruslan Sokolovsky Abdul Shakoor RUSSIAN Raif Badawi Ashraf Fayadh Shankar Ponnam PAKISTAN FEDERATION SAUDI ARABIA SAUDI ARABIA SAUDI ARABIA UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM SELECTED BLASPHEMY CASES SEPTEMBER 2017 WWW.USCIRF.GOV COMMISSIONERS Daniel Mark, Chairman Sandra Jolley, Vice Chair Kristina Arriaga de Bucholz, Vice Chair Tenzin Dorjee Clifford D. May Thomas J. Reese, S.J. John Ruskay Jackie Wolcott Erin D. Singshinsuk Executive Director PROFESSIONAL STAFF Dwight Bashir, Director of Research and Policy Elizabeth K. Cassidy, Director of International Law and Policy Judith E. Golub, Director of Congressional Affairs & Policy and Planning John D. Lawrence, Director of Communications Elise Goss-Alexander, Researcher Andrew Kornbluth, Policy Analyst Tiffany Lynch, Senior Policy Analyst Tina L. Mufford, Senior Policy Analyst Jomana Qaddour, Policy Analyst Karen Banno, Office Manager Roy Haskins, Manager of Finance and Administration Travis Horne, Communications Specialist SELECTED BLASPHEMY CASES Many countries today have blasphemy laws. Blasphemy is defined as “the act of insulting or showing contempt or lack of reverence for God.” Across the globe, billions of people view blasphemy as deeply offensive to their beliefs. Respecting Rights? Measuring the World’s • Violate international human rights standards; Blasphemy Laws, a U.S. Commission on Inter- • Often are vaguely worded, and few specify national Religious Freedom (USCIRF) report, or limit the forum in which blasphemy can documents the 71 countries – ranging from occur for purposes of punishment; Canada to Pakistan – that have blasphemy • Are inconsistent with the approach laws (as of June 2016). -

Universal Periodic Review 2009

UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW 2009 SAUDI ARABIA NGO: European Centre for Law and Justice 4, Quai Koch 67000 Strasbourg France RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IN THE SAUDI ARABIA SECTION 1: Legal Framework I. Saudi Constitutional Provisions Saudi Arabia is an Islamic monarchy.1 The Saudi Constitution is comprised of the Koran, Sharia law, and the Basic Law.2 “Islamic law forms the basis for the country’s legal code.”3 Strict Islamic law governs,4 and as such, the Saudi Constitution does not permit religious freedom. Even the practice of Islam itself is limited to the strict, Saudi-specific interpretation of Islam.5 Importantly, the Saudi government makes essentially no distinction between religion and government.6 According to its constitution, Saudi Arabia is a monarchy with a limited Consultative Council and Council of Ministers.7 The Consultative Council is governed by the Shura Council Law, which is based on Islam,8 and serves as an advisory body that operates strictly within the traditional confines of Islamic law.9 The Council of Ministers, expressly recognized by the Basic Law,10 is authorized to “examine almost any matter in the kingdom.”11 The Basic Law was promulgated by the king in 1993 and operates somewhat like a limited “bill of rights” for Saudi citizens. Comprising a portion of the Saudi Constitution, the Basic Law broadly outlines “the government’s rights and responsibilities,” as well as the general structure of government and the general source of law (the Koran). 12 The Basic Law consists of 83 articles defining the strict, Saudi Islamic state. By declaring that Saudi Arabia is an Islamic state and by failing to make any 1 U.S. -

Release Teacher Accused of Blasphemy

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL PRESS RELEASE AI Index: PRE 01/228/2013 10 May 2013 Egypt: Release teacher accused of blasphemy A Coptic Christian teacher detained in Egypt on charges of “defamation of religion” must be immediately released and the criminal case against her dropped, said Amnesty International today, ahead of her appearance in court on Saturday. Dimyana Obeid Abd Al Nour, 24, has been in custody since 8 May, when she went to the public prosecution’s office in Luxor to respond to charges of “defamation of religion”. The case against her is based on a complaint lodged by the parents of three of her students alleging that she insulted Islam and the Prophet Muhammad during a class. The alleged incident took place at the Sheikh Sultan primary school in Tout, Luxor Governorate, on 8 April during a lesson on “religious life”. Dimyana Obeid Abd Al Nour has been teaching at three schools in Luxor since the beginning of this year. “It is outrageous that a teacher finds herself behind bars for teaching a class. If she made some professional mistake, or deviated from the school curriculum, an internal review should have sufficed,” said Hassiba Hadj Sahraoui, Deputy Middle East and North Africa Programme Director at Amnesty International. “The authorities must release Dimyana Obeid Abd Al Nour immediately and drop these spurious charges against her.” According to the information available to Amnesty International, some of the students alleged that Dimyana Obeid Abd Al Nour said that she “loved Father Shenouda”, the late Patriarch of the Egyptian Orthodox Church, and touched her knee or her stomach when she spoke about the Prophet Muhammad in class. -

Blasphemy in a Secular State: Some Reflections

BLASPHEMY IN A SECULAR STATE: SOME REFLECTIONS Belachew Mekuria Fikre ♣ Abstract Anti-blasphemy laws have endured criticism in light of the modern, secular and democratic state system of our time. For example, Ethiopia’s criminal law provisions on blasphemous utterances, as well as on outrage to religious peace and feeling, have been maintained unaltered since they were enacted in 1957. However, the shift observed within the international human rights discourse tends to consider anti-blasphemy laws as going against freedom of expression. The recent Human Rights Committee General Comment No. 34 calls for a restrictive application of these laws for the full realisation of many of the rights within the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Secularism and human rights perspectives envisage legal protection to the believer and not the belief. Lessons can be drawn from the legal framework of defamation which considers injuries to the person rather than to institutions or to the impersonal sacred truth. It is argued that secular states can ‘promote reverence at the public level for private feelings’ through well-recognised laws of defamation and prohibition of hate speech rather than laws of blasphemy. This relocates the role of the state to its proper perspective in the context of its role in promoting interfaith dialogue, harmony and tolerance. Key words Blasphemy, Secular, Human Rights, Freedom of Expression, Defamation of Religion DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/mlr.v7i1.2 _____________ Introduction The secular as ‘an epistemic category’, and secularism as a value statement, have been around since the 1640s Peace of Westphalia, otherwise called the ‘peace of exhaustion’, and they remain one of the contested issues in today’s world political discourse. -

United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is a federation of seven states formed in 1971. It is governed by a Supreme Council of Rulers made up of the seven emirs, who appoint the prime minister and the cabinet. Islam is the country’s official religion. The UAE is a member of the League of Arab States (LAS), as well as the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). An estimated 88 percent of residents are noncitizens, largely consisting of migrant workers from India or the Philippines. More than 85 percent of UAE citizens are Sunni Muslims and an estimated 15 percent or fewer are Shia Muslims.[ref]https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/UNITED-ARAB-E MIRATES-2018-INTERNATIONAL-RELIGIOUS-FREEDOM-REPORT.pdf[/ref] From March 2015 to February 2020, the UAE, along with Saudi Arabia, led an armed intervention against Houthi forces in Yemen. The armed conflict has created one of the world’s most devastating humanitarian crises, with 80% of the Yemeni population (more than 24 million people) now dependent on aid.[ref]https://www.unicef.org/emergencies/yemen-crisis[/ref] Thousands of Yemeni citizens have been killed in unlawful airstrikes, which have hit homes, markets, hospitals, schools, and mosques.[ref]https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/yemen#c4 3786[/ref] Constitution and Education and Family, Freedom of government children’s rights community, expression society, religious advocacy of courts and humanist values tribunals State legislation is It is illegal to Expression of core largely or entirely register -

Measuring the World's Blasphemy Laws

RESPECTING RIGHTS? Measuring the World’s Blasphemy Laws U.S. COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM A gavel is seen in a hearing room in Panama City April 7, 2016. REUTERS/Carlos Jasso UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM RESPECTING RIGHTS? Measuring the World’s Blasphemy Laws By Joelle Fiss and Jocelyn Getgen Kestenbaum JULY 2017 WWW.USCIRF.GOV COMMISSIONERS Daniel Mark, Chairman Sandra Jolley, Vice Chair Kristina Arriaga de Bucholz, Vice Chair Tenzin Dorjee Clifford D. May Thomas J. Reese, S.J. John Ruskay Jackie Wolcott Erin D. Singshinsuk Executive Director PROFESSIONAL STAFF Dwight Bashir, Director of Research and Policy Elizabeth K. Cassidy, Director of International Law and Policy Judith E. Golub, Director of Congressional Affairs & Policy and Planning John D. Lawrence, Director of Communications Sahar Chaudhry, Senior Policy Analyst Elise Goss-Alexander, Researcher Andrew Kornbluth, Policy Analyst Tiffany Lynch, Senior Policy Analyst Tina L. Mufford, Senior Policy Analyst Jomana Qaddour, Policy Analyst Karen Banno, Office Manager Roy Haskins, Manager of Finance and Administration Travis Horne, Communications Specialist This report, containing data collected, coded, and analyzed as of June 2016, was overseen by Elizabeth K. Cassidy, J.D., LL.M, Director of International Law and Policy at the U.S. Commis- sion on International Religious Freedom. At USCIRF, Elizabeth is a subject matter expert on international and comparative law issues related to religious freedom as well as U.S. refugee and asylum policy. -

Religion, Tolerance and Discrimination in Malta

RELIGION, TOLERANCE AND DISCRIMINATION IN MALTA ALFRED GRECH Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief Political legitimacy is a central issue. Since religion can be a powerful legitimizing force for society, the likelihood of achieving religious liberty, and therefore non-discrimination on the basis of religion is often reduced to the extent that the regime’s political legitimacy is weak. Such a regime is likely to exploit the legitimizing power of the dominant religion with the corresponding risks of oppression for dissenting groups. A State which is confessional, or has a dominant religion may be a democracy in its own right, and may also embrace human rights guarantees, but to what extent is the fundamental right to freedom of conscience safeguarded when the State decides how far and to what extent a ruling religion or the religion of the state determines or interferes with the political life of the country? It would appear that in situations like these the majority or the ruling class can determine the religious rights of everyone including the dissenting minority, which does not identify itself with the State religion. In such a case religion or the state religion interferes with, if it does not determine the political agenda.1 Article 2 of the Constitution of Malta provides: 2 (1) The religion of Malta is the Roman Catholic Apostolic Religion. (2) The authorities of the Roman Catholic Apostolic Church have the duty and the right to teach which principles are right and which are wrong. (3) Religious teaching of the Roman Catholic Apostolic Faith shall be provided in all State schools as part of compulsory education.