Fox Television Stations, Inc. V. Aereokiller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nexstar Media Group Stations(1)

Nexstar Media Group Stations(1) Full Full Full Market Power Primary Market Power Primary Market Power Primary Rank Market Stations Affiliation Rank Market Stations Affiliation Rank Market Stations Affiliation 2 Los Angeles, CA KTLA The CW 57 Mobile, AL WKRG CBS 111 Springfield, MA WWLP NBC 3 Chicago, IL WGN Independent WFNA The CW 112 Lansing, MI WLAJ ABC 4 Philadelphia, PA WPHL MNTV 59 Albany, NY WTEN ABC WLNS CBS 5 Dallas, TX KDAF The CW WXXA FOX 113 Sioux Falls, SD KELO CBS 6 San Francisco, CA KRON MNTV 60 Wilkes Barre, PA WBRE NBC KDLO CBS 7 DC/Hagerstown, WDVM(2) Independent WYOU CBS KPLO CBS MD WDCW The CW 61 Knoxville, TN WATE ABC 114 Tyler-Longview, TX KETK NBC 8 Houston, TX KIAH The CW 62 Little Rock, AR KARK NBC KFXK FOX 12 Tampa, FL WFLA NBC KARZ MNTV 115 Youngstown, OH WYTV ABC WTTA MNTV KLRT FOX WKBN CBS 13 Seattle, WA KCPQ(3) FOX KASN The CW 120 Peoria, IL WMBD CBS KZJO MNTV 63 Dayton, OH WDTN NBC WYZZ FOX 17 Denver, CO KDVR FOX WBDT The CW 123 Lafayette, LA KLFY CBS KWGN The CW 66 Honolulu, HI KHON FOX 125 Bakersfield, CA KGET NBC KFCT FOX KHAW FOX 129 La Crosse, WI WLAX FOX 19 Cleveland, OH WJW FOX KAII FOX WEUX FOX 20 Sacramento, CA KTXL FOX KGMD MNTV 130 Columbus, GA WRBL CBS 22 Portland, OR KOIN CBS KGMV MNTV 132 Amarillo, TX KAMR NBC KRCW The CW KHII MNTV KCIT FOX 23 St. Louis, MO KPLR The CW 67 Green Bay, WI WFRV CBS 138 Rockford, IL WQRF FOX KTVI FOX 68 Des Moines, IA WHO NBC WTVO ABC 25 Indianapolis, IN WTTV CBS 69 Roanoke, VA WFXR FOX 140 Monroe, AR KARD FOX WTTK CBS WWCW The CW WXIN FOX KTVE NBC 72 Wichita, KS -

Fox Corporation and Comcast Announce Long-Term Distribution Agreement

Fox Corporation and Comcast Announce Long-term Distribution Agreement April 1, 2020 Los Angeles, CA and Philadelphia, PA – April 1, 2020 – Fox Corporation (Nasdaq: FOXA, FOX) and Comcast Corporation (Nasdaq: CMCSA) today announced a long-term renewal of their distribution agreement for FOX’s full portfolio of channels, including retransmission consent for the FOX Television Stations to Xfinity customers. Michael Biard, President of Operations and Distribution for FOX commented, “We are pleased to extend our longstanding and productive partnership with Comcast so that millions of Xfinity customers will continue to enjoy FOX’s leading sports, entertainment and news programming for years to come.” Rebecca Heap, Senior Vice President of Video and Entertainment for Comcast Cable said, “We are pleased to have reached this multi-year agreement with FOX to continue to deliver its array of content across our platforms for Xfinity TV customers.” The renewal covers distribution of the FOX Television Stations, FOX News Channel, FOX Business, FS1, FS2, BTN, and FOX Deportes. In addition, the agreement includes video-on-demand and TV Everywhere rights for those networks, enabling Xfinity customers to watch a wide array of FOX programming, live and on-demand, through the Xfinity Stream, FOX NOW, FOX Sports and FOX News apps with state-of-the-art dynamic advertising. About Fox Corporation Fox Corporation produces and distributes compelling news, sports and entertainment content through its iconic domestic brands including: FOX News Media, FOX Sports, FOX Entertainment, and FOX Television Stations. These brands hold cultural significance with consumers and commercial importance for distributors and advertisers. The breadth and depth of our footprint allows us to deliver content that engages and informs audiences, develop deeper consumer relationships and create more compelling product offerings. -

All Full-Power Television Stations by Dma, Indicating Those Terminating Analog Service Before Or on February 17, 2009

ALL FULL-POWER TELEVISION STATIONS BY DMA, INDICATING THOSE TERMINATING ANALOG SERVICE BEFORE OR ON FEBRUARY 17, 2009. (As of 2/20/09) NITE HARD NITE LITE SHIP PRE ON DMA CITY ST NETWORK CALLSIGN LITE PLUS WVR 2/17 2/17 LICENSEE ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX NBC KRBC-TV MISSION BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX CBS KTAB-TV NEXSTAR BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX FOX KXVA X SAGE BROADCASTING CORPORATION ABILENE-SWEETWATER SNYDER TX N/A KPCB X PRIME TIME CHRISTIAN BROADCASTING, INC ABILENE-SWEETWATER SWEETWATER TX ABC/CW (DIGITALKTXS-TV ONLY) BLUESTONE LICENSE HOLDINGS INC. ALBANY ALBANY GA NBC WALB WALB LICENSE SUBSIDIARY, LLC ALBANY ALBANY GA FOX WFXL BARRINGTON ALBANY LICENSE LLC ALBANY CORDELE GA IND WSST-TV SUNBELT-SOUTH TELECOMMUNICATIONS LTD ALBANY DAWSON GA PBS WACS-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY PELHAM GA PBS WABW-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY VALDOSTA GA CBS WSWG X GRAY TELEVISION LICENSEE, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ADAMS MA ABC WCDC-TV YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY NBC WNYT WNYT-TV, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY ABC WTEN YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY FOX WXXA-TV NEWPORT TELEVISION LICENSE LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY AMSTERDAM NY N/A WYPX PAXSON ALBANY LICENSE, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY PITTSFIELD MA MYTV WNYA VENTURE TECHNOLOGIES GROUP, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CW WCWN FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY PBS WMHT WMHT EDUCATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CBS WRGB FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. -

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Fox Corp. Request for Permanent Waiver of ) MB Docket No. 20-378 Newspaper-Broadcast Cross-Ownership Rule ) ) OPPOSITION OF FREE PRESS, UNITED CHURCH OF CHRIST, OC INC., AND COMMON CAUSE TO FOX CORP. REQUEST FOR PERMANENT WAIVER Carmen D. Scurato Matthew F. Wood Jessica J. González Free Press 1025 Connecticut Ave. NW, Suite 1110 Washington DC, 20036 (202) 265-1490 December 1, 2020 Executive Summary Free Press, United Church of Christ, OC Inc., and Common Cause oppose Fox’s request for a permanent waiver of the newspaper-broadcast cross-ownership rule for WWOR-TV, Secaucus, NJ, and the New York Post newspaper. The Commission must deny Fox’s request for a permanent waiver for three reasons: (1) the request is legally deficient, failing to meet or even address the 2016 QR Order’s standard of review for an NBCO waiver; (2) Fox’s past waiver requests and grants alone do not support granting a permanent waiver now; and (3) the Commission should not rule on the waiver during this time, with the pending transition in the presidential administration and at the Commission as well, plus the pending Supreme Court review of the proceeding setting forth this rule Fox has been dodging for the past nineteen years. First, the Commission should reject the request because it is not tethered to the law, and Fox’s minimal attempt to plead a case for such extraordinary relief is deficient. Fox fails to articulate any waiver standard by which its request for a permanent waiver should be measured. -

Filmed Entertainment Television Dire Sate Cable Network Programming

AsNews of June 30, 2011 Corporation News Corporation is a diversified global media company, which principally consists of the following: Cable Network Taiwan Fox 2000 Pictures KTXH Houston, TX Asia Australia Programming STAR Chinese Channel Fox Searchlight Pictures KSAZ Phoenix, AZ Tata Sky Limited 30% Almost 150 national, metropolitan, STAR Chinese Movies Fox Music KUTP Phoenix, AZ suburban, regional and Sunday titles, United States Channel [V] Taiwan Twentieth Century Fox Home WTVT Tampa B ay, FL Australia and New Zealand including the following: FOX News Channel Entertainment KMSP Minneapolis, MN FOXTEL 25% The Australian FOX Business Network China Twentieth Century Fox Licensing WFTC Minneapolis, MN Sky Network Television The Weekend Australian Fox Cable Networks Xing Kong 47% and Merchandising WRBW Orlando, FL Limited 44% The Daily Telegraph FX Channel [V] China 47% Blue Sky Studios WOFL Orlando, FL The Sunday Telegraph Fox Movie Channel Twentieth Century Fox Television WUTB Baltimore, MD Publishing Herald Sun Fox Regional Sports Networks Other Asian Interests Fox Television Studios WHBQ Memphis, TN Sunday Herald Sun Fox Soccer Channel ESPN STAR Sports 50% Twentieth Television KTBC Austin, TX United States The Courier-Mail SPEED Phoenix Satellite Television 18% WOGX Gainesville, FL Dow Jones & Company, Inc. Sunday Mail (Brisbane) FUEL TV United States, Europe, Australia, The Wall Street Journal The Advertiser FSN Middle East & Africa New Zealand Australia and New Zealand Barron’s Sunday Mail (Adelaide) Fox College Sports Rotana 15% -

Federal Communications Commission DA 11-521 Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission DA 11-521 Before the Federal Communications Commission WASHINGTON, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Fox Television Stations, Inc. ) File Number: EB-06-IH-3709 ) Facility ID Number: 68883 Licensee of Station KMSP-TV, ) NAL/Acct. Number: 201132080023 Minneapolis, Minnesota ) FRN: 0005795067 NOTICE OF APPARENT LIABILITY FOR FORFEITURE Adopted: March 24, 2011 Released: March 24, 2011 By the Chief, Enforcement Bureau: I. INTRODUCTION 1. In this Notice of Apparent Liability for Forfeiture (“NAL”), we assess a monetary forfeiture in the amount of four thousand dollars ($4,000) against Fox Television Stations, Inc. (“Fox” or “the Licensee”), licensee of Station KMSP-TV, Minneapolis, Minnesota (“Station KMSP-TV” or “the Station”), for its apparent willful violation of section 317 of the Communications Act, as amended (“the Act”), and section 73.1212 of the Commission’s rules.1 As discussed below, we find that Fox apparently violated section 317 of the Act and the Commission’s sponsorship identification rule. II. BACKGROUND 2. The Commission received a complaint jointly filed by Free Press and the Center for Media and Democracy (“CMD”) alleging that Fox’s Station KMSP-TV had aired a Video News Release (“VNR”) produced for General Motors without also airing a sponsorship identification announcement.2 The Enforcement Bureau (“Bureau”) issued a letter of inquiry to the Licensee concerning the allegations raised in the Complaint.3 3. Fox responded to the LOI and stated that Station KMSP-TV had broadcast a news report on June 19, 2006, relating to new car designs that included the General Motors VNR.4 Fox further stated 1 See 47 U.S.C. -

Federal Communications Commission DA 96-1852 WJW License, Inc. ) W

Federal Communications Commission DA 96-1852 WJW License, Inc. ) W.IW-TV. Cleveland. Ohio ) BTCCT-960813IS WITI License. Inc. © ) WITI-TV. Milwaukee. Wisconsin ) BTCCT-960813IT TVT License. Inc. ) WTVT(TV). Tampa. Florida ) BTCCT-960813IU MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER Adopted: November 7, 1996 Released: November 7, 1996 By the Chief, Mass Media Bureau: 1. The Commission, by the Chief. Mass Media Bureau, acting pursuant to delegated authority, has before it for consideration the above-captioned applications seeking consent to the transfer of control of New World Communications Group Inc. (New World), and its subsidiaries from NWCG (Parent) Holdings Corp. and NWCG Holdings Corp. to Fox Television Stations. Inc. (Fox). Pursuant to an Agreement and Plan of Merger and a Stock Purchase Agreement between the parties, New World will become a wholly-owned subsidiary of Fox. The National Association of Broadcast Employees and Technicians, the Broadcast and Broadcast Cable Television Sector of the Communications Workers of America, AFL-CIO, Local No. 43 (NABET), timely filed a petition to deny the transaction. 2. New World, through several holding companies, wholly owns the stock of the licensees of the ten television stations and seven television translators referenced above. Fox controls the licenses of 12 television stations, including station WFLD(TV) (Fox), Channel 32, Chicago. Illinois. Because the Grade B contour of station WFLD(TV) overlaps with that of New World station WITI-TV (Fox), Channel 6, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, common ownership of both stations by Fox will contravene the Commission©s duopoly rule. Section 73.3555(b), which proscribes common ownership of two television stations with overlapping Grade B contours. -

Broadcast Actions 1/28/2020

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 49662 Broadcast Actions 1/28/2020 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 01/21/2020 DIGITAL TV APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED WI BALCDT-20191119AAA WITI 73107 WITI LICENSE, LLC Voluntary Assignment of License, as amended From: WITI LICENSE, LLC E CHAN-33 WI , MILWAUKEE To: FOX TELEVISION STATIONS, LLC Form 314 WA BAL-20191119AAC KCPQ 33894 TRIBUNE BROADCASTING Voluntary Assignment of License, as amended SEATTLE, LLC From: TRIBUNE BROADCASTING SEATTLE, LLC E CHAN-22 To: FOX TELEVISION STATIONS, LLC WA ,TACOMA Form 314 WA BALCDT-20191119AAD KZJO 69571 TRIBUNE BROADCASTING Voluntary Assignment of License, as amended SEATTLE, LLC From: TRIBUNE BROADCASTING SEATTLE, LLC E CHAN-36 To: FOX TELEVISION STATIONS, LLC WA , SEATTLE Form 314 NC BALCDT-20191119AAL WJZY 73152 FOX TELEVISION STATIONS, LLC Voluntary Assignment of License, as amended From: FOX TELEVISION STATIONS, LLC E CHAN-25 NC , BELMONT To: NEXSTAR BROADCASTING, INC. Form 314 Page 1 of 8 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 49662 Broadcast Actions 1/28/2020 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 01/21/2020 DIGITAL TV APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED SC BALCDT-20191119AAM WMYT-TV FOX TELEVISION STATIONS, LLC Voluntary Assignment of License, as amended 20624 From: FOX TELEVISION STATIONS, LLC E SC ,ROCK HILL To: NEXSTAR BROADCASTING, INC. -

Fox News Co-Presidents Jack Abernethy and Bill Shine Sign New Multi-Year Contracts

FOX NEWS CO-PRESIDENTS JACK ABERNETHY AND BILL SHINE SIGN NEW MULTI-YEAR CONTRACTS NEW YORK – September 14, 2016 – FOX News co-presidents Jack Abernethy and Bill Shine have signed new multi-year contracts, announced Rupert Murdoch, Executive Chairman of 21st Century Fox and Executive Chairman of FOX News & FOX Business Network. In making the announcement, Murdoch said, “Jack and Bill have been instrumental in FOX News’ continued dominance in the ratings and historic earnings performance. I am delighted they’ve each signed new deals, ensuring stability and leadership to help guide the network for years to come.” Abernethy and Shine added, “We’re thrilled to have the opportunity to continue leading FOX News and FOX Business into the future and look forward to working alongside the incredible roster of talent, both on and off air, to make each network even more successful.” Promoted to co-presidents in August, Abernethy and Shine oversee both FOX News Channel (FNC) and FOX Business Network (FBN), dividing responsibilities for all facets of the networks. While continuing to run FOX Television Stations (FTS), Mr. Abernethy manages all business components of FNC and FBN including finance, advertising sales and distribution units. Mr. Shine runs all programming and news functions of each network, including production, technical operations and talent management. In his role as CEO of FOX Television Stations, Jack Abernethy oversees 28 owned and operated stations in the nation’s largest television markets, including WNYW/WWOR in New York, KTTV/KCOP in Los Angeles, KDFW/KDFI in Dallas, WTXF in Philadelphia, WTTG/WDCA in Washington, D.C. -

WITI-FOX 6, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

OVERVIEW: FOX Television Stations, LLC is one of the nation’s largest owned-and-operated network broadcast groups, covering over 37% of U.S. television homes. The FOX TV Stations markets include (*indicates a duopoly market): *New York, *Los Angeles, *Chicago, Philadelphia, *Dallas, *San Francisco, *Washington DC, *Houston, Atlanta, *Phoenix, Tampa, Detroit, *Seattle, *Minneapolis/St. Paul, *Orlando, Austin and Milwaukee. FOX6 Milwaukee is a leading local news organization and one of the strongest FOX stations in the country. JOB TITLE: Account Executive FOX6 Milwaukee is looking for an experienced OTT salesperson to develop and manage business for the FOX Local Extension OTT platform (FLX). The FLX platform has 150+ high quality video partners and preferred / direct access to FOX owned streaming networks. RESPONSIBILITIES: The FLX Account Executive is responsible for prospecting new business, present FLX capabilities via Zoom and in-person. Be the OTT/Streaming category expert, working alongside the FOX6 Milwaukee linear sales teams. Oversee all schedules throughout the campaign, work directly with stations, advertising agencies and clients to increase revenue for the FLX OTT/Streaming platform. QUALIFICATIONS: The ideal candidate will have 2-3 years of successful experience in the digital media industry; Digital Video Advertising and/or Digital Agency/Digital Publisher experience preferred. College degree preferred. IAB certification. Familiarity with basic digital media technology. Excellent presentation skills. Existing relationships with senior level client or agency decision makers. Digital agency relationships. Excellent communication skills, proficient in Word, Excel, PowerPoint. Wide Orbit a plus. Knowledge of the local TV marketplace and how they are adapting to new OTT channels. -

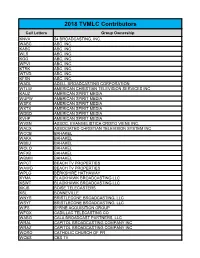

2018 TVMLC Contributors

2018 TVMLC Contributors Call Letters Group Ownership KNVA 54 BROADCASTING, INC. WABC ABC, INC. KABC ABC, INC. WLS ABC, INC. KGO ABC, INC. WPVI ABC, INC. KTRK ABC, INC. WTVD ABC, INC. KFSN ABC, INC. WADL ADELL BROADCASTING CORPORATION WTLW AMERICAN CHRISTIAN TELEVISION SERVICES INC KAUZ AMERICAN SPIRIT MEDIA WUPW AMERICAN SPIRIT MEDIA WSFX AMERICAN SPIRIT MEDIA WXTX AMERICAN SPIRIT MEDIA WDBD AMERICAN SPIRIT MEDIA KVHP AMERICAN SPIRIT MEDIA WVSN ASSOC. EVANGELISTICA CRISTO VIENE INC. WACX ASSOCIATED CHRISTIAN TELEVISION SYSTEM INC WCCB BAHAKEL WAKA BAHAKEL WBBJ BAHAKEL WOLO BAHAKEL WFXB BAHAKEL WBMM BAHAKEL WPCT BEACH TV PROPERTIES WAWD BEACH TV PROPERTIES WPLG BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY KYMA BLACKHAWK BROADCASTING LLC KSWT BLACKHAWK BROADCASTING LLC KKJB BOISE TELECASTERS KSL BONNEVILLE WNYS BRISTLECONE BROADCASTING, LLC WSYT BRISTLECONE BROADCASTING, LLC WIFS BYRNE ACQUISITION GROUP WFQX CADILLAC TELECASTING CO WABG CALA BROADCAST PARTNERS, LLC WRAL CAPITOL BROADCASTING COMPANY INC WRAZ CAPITOL BROADCASTING COMPANY INC WORO CATHOLIC CHURCH OF PR WCBS CBS TV KCBS CBS TV WBBM CBS TV KPIX CBS TV WBZ CBS TV KYW CBS TV KCAL CBS TV KCNC CBS TV WCCO CBS TV WJZ CBS TV KTVT CBS TV KOVR CBS TV KDKA CBS TV WFOR CBS TV KBCW CBS TV WSBK CBS TV WPSG CBS TV KSTW CBS TV KTXA CBS TV WKBD CBS TV WWJ CBS TV WUPA CBS TV WBFS CBS TV WTOG CBS TV KMAX CBS TV WLNY CBS TV WPCW CBS TV WGGN CHRISTIAN FAITH BROADCASTING WLLA CHRISTIAN FAITH BROADCASTING WISH CIRCLE CITY BROADCASTING INC WLNE CITADEL COMMUNICATIONS KLKN CITADEL COMMUNICATIONS WLOV COASTAL TELEVISION KTBY -

2019 Annual Report 2019 Report Annual

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ANNUAL REPORT 2019 A MESSAGE FROM RUPERT MURDOCH Dear Shareholders, transaction, this leadership team delivered consistently impressive results. In Fiscal Year This letter to my fellow shareholders marks the first 2019, FOX News continued its run as the dominant I am writing for our new company, Fox Corporation, cable news channel for 17 consecutive years and which is anchored by FOX News Media, FOX Sports, launched FOX Nation to deepen and expand the FOX Entertainment and FOX Television Stations. experience for our most dedicated FOX News The future for Fox Corporation, and each of our viewers. FOX Entertainment debuted The Masked brands, has never been brighter. Singer as the most successful new show of the In our abbreviated Fiscal Year 2019, we began to season. FOX Sports delivered flawless coverage unlock value for our shareholders and create a of a historic FIFA Women’s World Cup. And FOX distinctive and agile company poised for future Television Stations delivered nearly 1,000 hours growth. Fox Corporation has invested in strategic of local news each week in addition to popular growth opportunities, further enhancing our digital original programming. capabilities. We have also made acquisitions that With Lachlan at the helm, FOX will continue to complement our existing businesses, and diversify strengthen and expand. We are well-positioned to our revenue streams, all while staying true to the benefit from the rapidly changing media industry focused and nimble structure that differentiates us. by focusing on the content that Americans are most Across Fox Corporation, we remain committed to passionate about and enhancing the platforms we culture-defining entertainment, breaking news, offer for viewing and engagement.