Northern Leopard Frog (Rana Pipiens) Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Species Assessment for the Northern Leopard Frog (Rana Pipiens)

SPECIES ASSESSMENT FOR THE NORTHERN LEOPARD FROG (RANA PIPIENS ) IN WYOMING prepared by 1 2 BRIAN E. SMITH AND DOUG KEINATH 1Department of Biology Black Hills State University1200 University Street Unit 9044, Spearfish, SD 5779 2 Zoology Program Manager, Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, 1000 E. University Ave, Dept. 3381, Laramie, Wyoming 82071; 307-766-3013; [email protected] prepared for United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Wyoming State Office Cheyenne, Wyoming January 2004 Smith and Keinath – Rana pipiens January 2004 Table of Contents SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................................... 3 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 3 NATURAL HISTORY ........................................................................................................................... 5 Morphological Description ...................................................................................................... 5 Taxonomy and Distribution ..................................................................................................... 6 Taxonomy .......................................................................................................................................6 Distribution and Abundance............................................................................................................7 -

![CHIRICAHUA LEOPARD FROG (Lithobates [Rana] Chiricahuensis)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9108/chiricahua-leopard-frog-lithobates-rana-chiricahuensis-669108.webp)

CHIRICAHUA LEOPARD FROG (Lithobates [Rana] Chiricahuensis)

CHIRICAHUA LEOPARD FROG (Lithobates [Rana] chiricahuensis) Chiricahua Leopard Frog from Sycamore Canyon, Coronado National Forest, Arizona Photograph by Jim Rorabaugh, USFWS CONSIDERATIONS FOR MAKING EFFECTS DETERMINATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR REDUCING AND AVOIDING ADVERSE EFFECTS Developed by the Southwest Endangered Species Act Team, an affiliate of the Southwest Strategy Funded by U.S. Department of Defense Legacy Resource Management Program December 2008 (Updated August 31, 2009) ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This document was developed by members of the Southwest Endangered Species Act (SWESA) Team comprised of representatives from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM), U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (BoR), Department of Defense (DoD), Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), U.S. Forest Service (USFS), U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), National Park Service (NPS) and U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). Dr. Terry L. Myers gathered and synthesized much of the information for this document. The SWESA Team would especially like to thank Mr. Steve Sekscienski, U.S. Army Environmental Center, DoD, for obtaining the funds needed for this project, and Dr. Patricia Zenone, USFWS, New Mexico Ecological Services Field Office, for serving as the Contracting Officer’s Representative for this grant. Overall guidance, review, and editing of the document was provided by the CMED Subgroup of the SWESA Team, consisting of: Art Coykendall (BoR), John Nystedt (USFWS), Patricia Zenone (USFWS), Robert L. Palmer (DoD, U.S. Navy), Vicki Herren (BLM), Wade Eakle (USACE), and Ronnie Maes (USFS). The cooperation of many individuals facilitated this effort, including: USFWS: Jim Rorabaugh, Jennifer Graves, Debra Bills, Shaula Hedwall, Melissa Kreutzian, Marilyn Myers, Michelle Christman, Joel Lusk, Harold Namminga; USFS: Mike Rotonda, Susan Lee, Bryce Rickel, Linda WhiteTrifaro; USACE: Ron Fowler, Robert Dummer; BLM: Ted Cordery, Marikay Ramsey; BoR: Robert Clarkson; DoD, U.S. -

Northern Leopard Frog Reintroduction

Northern Leopard Frog Reintroduction Year 3 (2001) Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 42 Northern Leopard Frog Reintroduction Year 3 (2001) Kris Kendell Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 42 February 2002 Project Partners: Publication No.: I/059 ISBN: 0-7785-2014-5 (Printed Edition) ISBN: 0-7785-2015-3 (On-line Edition) ISSN: 1496-7146 (Printed Edition) ISSN: 1496-7146 (On-line Edition) Illustration: Brian Huffman For copies of this report, contact: Information Centre – Publications Alberta Environment/Alberta Sustainable Resource Development Main Floor, Great West Life Building 9920 108 Street Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T5K 2M4 Telephone: (780) 422-2079 OR Information Service Alberta Environment/Alberta Sustainable Resource Development #100, 3115 12 Street NE Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2E 7J2 Telephone: (403) 297-3362 OR Visit our web site at: http://www3.gov.ab.ca/srd/fw/riskspecies/ This publication may be cited as: Kendell, K. 2002. Northern leopard frog reintroduction: Year 3 (2001). Alberta Sustainable Resource Development, Fish and Wildlife Division, Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 42, Edmonton, AB. 45 pp. ii DISCLAIMER The views and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the policies or positions of the Department or the Alberta Government. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.......................................................................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .........................................................................................................viii -

Managing Forests for Fish and Wildlife

Wildlife Habitat Management Institute Managing Forests for Fish and Wildlife December 2002 Fish and Wildlife Habitat Management Leaflet Number 18 Forested areas can be managed with a wide variety of objectives, ranging from allowing natural processes to dictate long-term condition without active management of any kind, to maximizing production of wood products on the shortest rotations possible. The primary purpose of this document is to show how fish and wildlife habitat management can be effectively integrated into the management of forestlands that are subject to periodic timber harvest activities. For forestlands that are not managed for production of timber or other forest products, many of the principles U.S. Forest Service, Southern Research Station in this leaflet also apply. Introduction Succession of Forest Vegetation Forests in North America provide a wide variety of In order to meet both timber production and wildlife important natural resource functions. Although management goals, landowners and managers need commercial forests may be best known for production to understand how forest vegetation responds following of pulp, lumber, and other wood products, they also timber management, or silvicultural prescriptions, or supply valuable fish and wildlife habitat, recreational other disturbances. Forest vegetation typically opportunities, water quality protection, and other progresses from one plant community to another over natural resource benefits. In approximately two-thirds time. This forest succession can be described in four of the forest land (land that is at least 10% tree- stages: covered) in the United States, harvest of wood products plays an integral role in how these lands are managed. Sustainable forest management applies Fish and Wildlife Air and Water biological, economic, and social principles to forest Wood Products Habitat Quality regeneration, management, and conservation to meet the specific goals of landowners or managers. -

Northern Leopard Frogs Range from the Northern United States and Canada to the More Northern Parts of the Southwestern United States

COLORADO PARKS & WILDLIFE Leopard Frogs ASSESSING HABITAT QUALITY FOR PRIORITY WILDLIFE SPECIES IN COLORADO WETLANDS Species Distribution Range Northern leopard frogs range from the northern United States and Canada to the more northern parts of the southwestern United States. With the exception of a few counties, they occur throughout Colorado. Plains leopard frogs have a much smaller distribution than northern leopard frogs, occurring through the Great Plains into southeastern Arizona and eastern Colorado. NORTHERN LEOPARD FROG © KEITH PENNER / PLAINS LEOPARD FROG © RENEE RONDEAU, CNHP RONDEAU, FROGRENEE © LEOPARD PLAINS / PENNER FROGKEITH © LEOPARD NORTHERN Two species of leopard frogs occur in Colorado. Northern leopard frogs (Lithobates pipiens; primary photo, brighter green) are more widespread than plains leopard frogs (L. blairi; inset). eral, plains leopard frogs breed in more Species Description ephemeral ponds, while northern leopard Identification frogs use semi-permanent ponds. Two leopard frogs are included in this Diet guild: northern leopard frog (Lithobates Adult leopard frogs eat primarily insects pipiens) and plains leopard frog (L. blairi). and other invertebrates, including They are roughly the same size (3–4 inches crustaceans, mollusks, and worms, as as adults). Northern leopard frogs can be well as small vertebrates, such as other green or brown and plains leopard frogs amphibians and snakes. Leopard frog are typically brown. Both species have two tadpoles are herbivorous, eating mostly light dorsolateral ridges along the back; in free-floating algae, but also consuming plains leopard frog there is a break in this some animal material. ridge near the rear legs. Conservation Status Preferred Habitats Northern leopard frog populations have Due to their complicated life history traits, declined throughout their range; they are leopard frogs occupy many habitats during listed in all western states and Canada different seasons and stages of develop- as sensitive, threatened, or endangered. -

Checklist of Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals of New York

CHECKLIST OF AMPHIBIANS, REPTILES, BIRDS AND MAMMALS OF NEW YORK STATE Including Their Legal Status Eastern Milk Snake Moose Blue-spotted Salamander Common Loon New York State Artwork by Jean Gawalt Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Fish and Wildlife Page 1 of 30 February 2019 New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Fish and Wildlife Wildlife Diversity Group 625 Broadway Albany, New York 12233-4754 This web version is based upon an original hard copy version of Checklist of the Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals of New York, Including Their Protective Status which was first published in 1985 and revised and reprinted in 1987. This version has had substantial revision in content and form. First printing - 1985 Second printing (rev.) - 1987 Third revision - 2001 Fourth revision - 2003 Fifth revision - 2005 Sixth revision - December 2005 Seventh revision - November 2006 Eighth revision - September 2007 Ninth revision - April 2010 Tenth revision – February 2019 Page 2 of 30 Introduction The following list of amphibians (34 species), reptiles (38), birds (474) and mammals (93) indicates those vertebrate species believed to be part of the fauna of New York and the present legal status of these species in New York State. Common and scientific nomenclature is as according to: Crother (2008) for amphibians and reptiles; the American Ornithologists' Union (1983 and 2009) for birds; and Wilson and Reeder (2005) for mammals. Expected occurrence in New York State is based on: Conant and Collins (1991) for amphibians and reptiles; Levine (1998) and the New York State Ornithological Association (2009) for birds; and New York State Museum records for terrestrial mammals. -

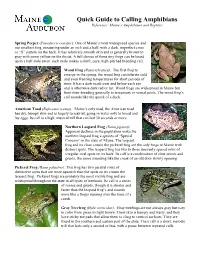

Quick Guide to Calling Amphibians Reference: Maine’S Amphibians and Reptiles

Quick Guide to Calling Amphibians Reference: Maine’s Amphibians and Reptiles Spring Peeper (Pseudacris crucifer): One of Maine’s most widespread species and our smallest frog, measuring under an inch and a half, with a dark, imperfect cross or “X” pattern on the back. It has relatively smooth skin and is generally brown to gray with some yellow on the throat. A full chorus of these tiny frogs can be heard up to a half-mile away; each male makes a shrill, pure, high-pitched breeding call. Wood Frog (Rana sylvatica): The first frog to emerge in the spring, the wood frog can tolerate cold and even freezing temperatures for short periods of ©USGS NEARMI time. It has a dark mask over and below each eye ©USGS NEARMI and is otherwise dark red or tan. Wood frogs are widespread in Maine but limit their breeding generally to temporary or vernal pools. The wood frog’s call sounds like the quack of a duck. ©James Hardy ©James Hardy American Toad (Bufo americanus): Maine’s only toad, the American toad has dry, bumpy skin and is largely terrestrial, going in water only to breed and lay eggs. Its call is a high, musical trill that can last 30 seconds or more. Northern Leopard Frog (Rana pipiens): Apparent declines in the population make the northern leopard frog a species of “Special Concern” in the state of Maine. The leopard frog and its close cousin the pickerel frog are the only frogs in Maine with distinct spots. The leopard frog has two to three unevenly spaced rows of irregular oval spots on its back. -

Southern Leopard Frog

Species Status Assessment Class: Amphibia Family: Ranidae Scientific Name: Lithobates sphenocephalus utricularius Common Name: Southern leopard frog Species synopsis: NOTE: More than a century of taxonomic confusion regarding the leopard frogs of the East Coast was resolved in 2012 with the publication of a genetic analysis (Newman et al. 2012) confirming that a third, cryptic species of leopard frog (Rana [= Lithobates] sp. nov.) occurs in southern New York, northern New Jersey, and western Connecticut. The molecular evidence strongly supported the distinction of this new species from the previously known northern (R. pipiens [= L. pipiens]) and southern (R. sphenocephala [=L. sphenocephalus]) leopard frogs. The new species’ formal description, which presents differences in vocalizations, morphology, and habitat affiliation (Feinberg et al. in preparation), is nearing submission for publication. This manuscript also presents bioacoustic evidence of the frog’s occurrence in southern New Jersey, Maryland, Delaware, and as far south as the Virginia/North Carolina border, thereby raising uncertainty about which species of leopard frog occur(s) presently and historically throughout the region. Some evidence suggests that Long Island might at one time have had two species: the southern leopard frog in the pine barrens and the undescribed species in coastal wetlands and the Hudson Valley. For simplicity’s sake, in this assessment we retain the name “southern leopard frog” even though much of the information available may refer to the undescribed species or a combination of species. The southern leopard frog occurs in the eastern United States and reaches the northern extent of its range in the lower Hudson Valley of New York. -

WDFW Status Report for the Northern Leopard Frog

STATE OF WASHINGTON October 1999 WashingtonWashington StateState StatusStatus ReportReport forfor thethe NorthernNorthern LeopardLeopard FrogFrog by Kelly R. McAllister, William P. Leonard, Dave W. Hays and Ronald C. Friesz WWashingtonashington Department of FISH AND WILDLIFE WWildlifeildlife Management Program WDFW 632 Washington State Status Report for the Northern Leopard Frog by Kelly R. McAllister William P. Leonard David W. Hays and Ronald C. Friesz Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Wildlife Management Program 600 Capitol Way N Olympia, Washington 98501-1091 October 1999 The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife maintains a list of endangered, threatened and sensitive species (Washington Administrative Codes 232-12-014 and 232-12-011, Appendix). In 1990, the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission adopted listing procedures developed by a group of citizens, interest groups, and state and federal agencies (Washington Administrative Code 232-12-297, Appendix). The procedures include how species listing will be initiated, criteria for listing and delisting, public review and recovery and management of listed species. The first step in the process is to develop a preliminary species status report. The report includes a review of information relevant to the species’ status in Washington and addresses factors affecting its status including, but not limited to: historic, current, and future species population trends, natural history including ecological relationships, historic and current habitat trends, population demographics and their relationship to long term sustainability, and historic and current species management activities. The procedures then provide for a 90-day public review opportunity for interested parties to submit new scientific data relevant to the status report, classification recommendation, and any State Environmental Policy Act findings. -

Columbia Spotted Frog (Rana Luteiventris) in Southeastern Oregon: a Survey of Historical Localities, 2009

Prepared in cooperation with the Oregon/Washington U.S. Bureau of Land Management and Region 6 U.S. Forest Service Interagency Special Status/Sensitive Species Program (ISSSSP) Columbia Spotted Frog (Rana luteiventris) in Southeastern Oregon: A Survey of Historical Localities, 2009 By Christopher A. Pearl, Stephanie K. Galvan, Michael J. Adams, and Brome McCreary Open-File Report 2010–1235 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Photographs of Oregon spotted frog and pond survey site. Photographs by the U.S. Geological Survey. Columbia Spotted Frog (Rana luteiventris) in Southeastern Oregon: A Survey of Historical Localities, 2009 By Christopher A. Pearl, Stephanie K. Galvan, Michael J. Adams, and Brome McCreary Prepared in cooperation with the Oregon/Washington U.S. Bureau of Land Management and Region 6 U.S. Forest Service Interagency Special Status/Sensitive Species Program (ISSSSP) Open-File Report 2010-1235 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2010 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod. To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov. Suggested citation: Pearl, C.A., Galvan, S.K., Adams, M.J., and McCreary, B., 2010, Columbia spotted frog (Rana luteiventris) in southeastern Oregon: A survey of historical localities, 2009: U.S. -

Amphibian Identifier 20

21 MOLE SALAMANDERS Family Ambystomatidae Amphibian Identifier 20 Long-toed Salamander Tiger Salamander 19 Ambystoma macrodactylum Ambystoma mavortium • Yellow or olive-green stripe from head to tip HIND FOOT 18 • Dark spots and stripes often creating a net-like pattern; of tail; may be broken into a series of blotches may become relatively uniform in colour and spotted with age 1 • Fine white or bluish flecks on sides and legs • Broad and flat head, with small eyes 2 17 • Long fourth toe on each hind foot • Background colour: yellow-brown, grey, olive-green to black • Background colour: brownish-grey to black 3 • Total length: up to 25 cm 5 16 • Total length: up to 15 cm 4 Long-toed salamander 15 14 13 Tiger salamander 12 photo: John P. Clare photo: ACA, Kris Kendell 11 TRUE FROGS Family Ranidae 10 9 Northern Leopard Frog Wood Frog Columbia Spotted Frog Lithobates pipiens 8 Lithobates sylvaticus Rana luteiventris • White or cream-coloured ridges of skin (dorsolateral folds) • Dark eye mask extends from snout through eye, ending • Small irregular dark spots with light centers 7 along sides of back behind eardrum; contrasts sharply with whitish jaw stripe • Underside of hind legs and lower belly becomes • Large round or oval dark spots with light borders • Ridges of skin (dorsolateral folds) along sides of back orange-red or pinkish with age • Background colour: green to brown 6 • May have light stripe down middle of back • Ridges of skin (dorsolateral folds) or tan; rarely golden • Background colour: brown, pink-tan, olive-green, grey along sides of back • Body length: up to 13 cm 5 to almost black • Eyes positioned towards top of • Call: three or more snore-like sounds • Body length: up to 8 cm head and angled upwards followed by interspersed grunting and 4 • Call: series of short, raspy • Background colour: light to dark brown chuckling sounds duck-like quacking sounds • Body length: up to 10 cm 3 • Call: series of quick low-pitched click sounds 2 photo: ACA, Kris Kendell 1 photo: Twan Leenders photo: Richard D. -

Management Plan for the Northern Leopard Frog (Lithobates Pipiens), Western Boreal/ Prairie Populations, in Canada

Species at Risk Act Management Plan Series Management Plan for the Northern Leopard Frog (Lithobates pipiens), Western Boreal/ Prairie Populations, in Canada Northern Leopard Frog, Western Boreal/ Prairie Populations 2013 Recommended citation: Environment Canada. 2013. Management Plan for the Northern Leopard Frog (Lithobates pipiens), Western Boreal/Prairie Populations, in Canada. Species at Risk Act Management Plan Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. iii + 28 pp. For copies of the management plan, or for additional information on species at risk, including COSEWIC Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry (www.sararegistry.gc.ca). Cover photo: Kelly Boyle Également disponible en français sous le titre « Plan de gestion de la grenouille léopard (Lithobates pipiens), populations des Prairies et de l’ouest de la zone boréale, au Canada » © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2013. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-100-20966-1 Catalogue no. En3-5/37-2013E-PDF Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source. Management Plan for the Northern Leopard Frog, Western Boreal/Prairie Populations 2013 PREFACE The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996) agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. Under the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c.29) (SARA), the federal competent ministers are responsible for the preparation of management plans for listed Special Concern species and are required to report on progress within five years.