Malta's Relations with the Holy See in Postcolonial Times (Since 1964)1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Educator a Journal of Educational Matters

No.5/2019 EDITORIAL BOARD Editor-in-Chief: Comm. Prof. George Cassar Editorial members: Marco Bonnici, Christopher Giordano Design and Printing: Print Right Ltd Industry Road, Ħal Qormi - Malta Tel: 2125 0994 A publication of the Malta Union of Teachers © Malta Union of Teachers, 2019. ISSN: 2311-0058 CONTENTS ARTICLES A message from the President of the Malta Union of Teachers 1 A national research platform for Education Marco Bonnici A union for all seasons – the first century 3 of the Malta Union of Teachers (1919-2019) George Cassar Is it time to introduce a Quality Rating and Improvement System 39 (QRIS) for childcare settings in Malta to achieve and ensure high quality Early Childhood Education and Care experiences (ECEC)? Stephanie Curmi Social Studies Education in Malta: 61 A historical outline Philip E. Said How the Economy and Social Status 87 influence children’s attainment Victoria Mallia & Christabel Micallef Understanding the past with visual images: 101 Developing a framework for analysing moving-image sources in the history classroom Alexander Cutajar The Educator A journal of educational matters The objective of this annual, peer-reviewed journal is to publish research on any aspect of education. It seeks to attract contributions which help to promote debate on educational matters and present new or updated research in the field of education. Such areas of study include human development, learning, formal and informal education, vocational and tertiary education, lifelong learning, the sociology of education, the philosophy of education, the history of education, curriculum studies, the psychology of education, and any other area which is related to the field of education including teacher trade unionism. -

IT-TLETTAX-IL LEĠIŻLATURA P.L. 4462 Raymond Scicluna Skrivan Tal-Kamra

IT-TLETTAX-IL LEĠIŻLATURA P.L. 4462 Dokument imqiegħed fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra tad-Deputati fis-Seduta Numru 299 tas-17 ta’ Frar 2020 mill-Ministru fl-Uffiċċju tal-Prim Ministru, f’isem il-Ministru għall-Wirt Nazzjonali, l-Arti u Gvern Lokali. ___________________________ Raymond Scicluna Skrivan tal-Kamra BERĠA TA' KASTILJA - INVENTARJU TAL-OPRI TAL-ARTI 12717. L-ONOR. JASON AZZOPARDI staqsa lill-Ministru għall-Wirt Nazzjonali, l-Arti u l-Gvern Lokali: Jista' l-Ministru jwieġeb il-mistoqsija parlamentari 8597 u jgħid jekk hemmx u jekk hemm, jista’ jqiegħed fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra l-Inventarju tal-Opri tal-Arti li hemm fil- Berġa ta’ Kastilja? Jista’ jgħid liema minnhom huma proprjetà tal-privat (fejn hu l-każ) u liema le? 29/01/2020 ONOR. JOSÈ HERRERA: Ninforma lill-Onor. Interpellant li l-ebda Opra tal-Arti li tagħmel parti mill-Kollezjoni Nazzjonali ġewwa l-Berġa ta’ Kastilja m’hi proprjetà tal-privat. għaldaqstant qed inpoġġi fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra l-Inventarju tal-Opri tal-Arti kif mitlub mill- Onor. Interpellant. Seduta 299 17/02/2020 PQ 12717 -Tabella Berga ta' Kastilja - lnventarju tai-Opri tai-Arti INVENTORY LIST AT PM'S SEC Title Medium Painting- Madonna & Child with young StJohn The Baptist Painting- Portraits of Jean Du Hamel Painting- Rene Jacob De Tigne Textiles- banners with various coats-of-arms of Grandmasters Sculpture- Smiling Girl (Sciortino) Sculpture- Fondeur Figure of a lady (bronze statue) Painting- Dr. Lawrence Gonzi PM Painting- Francesco Buhagiar (Prime Minister 1923-1924) Painting- Sir Paul Boffa (Prime Minister 1947-1950) Painting- Joseph Howard (Prime Minister 1921-1923) Painting- Sir Ugo Mifsud (Prime Minister 1924-1927, 1932-1933) Painting- Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici (Prime Minister 1984-1987) Painting- Dom Mintoff (Prime Minister 1965-1958, 1971-1984) Painting- Lord Gerald Strickland (Prime Minister 1927-1932) Painting- Dr. -

Censu Tabone.Pdf

• CENSU Tabone THE MAN AND HIS CENTURY Published by %ltese Studies P.O.Box 22, Valletta VLT, Malta 2000 Henry Frendo 268058 © Henry Frendo 2000 [email protected] . All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. ISBN: 99932-0-094-8 (hard-back) ISBN: 99932-0-095-6 (paper-back) Published by ~ltese Studies P.O.Box 22, Valletta VLT, Malta 2000 Set in Times New Roman by Standard Publications Ltd., St Julian's, Malta http://www.independent.com.mt Printed at Interprint Ltd., Marsa, Malta TABLE OF CONTENTS Many Faces: A FULL LIFE 9 2 First Sight: A CHILDHOOD IN GOZO 17 3 The Jesuit Formation: A BORDER AT ST ALOYSIUS 34 4 Long Trousers: STUDENT LIFE IN THE 1930s 43 5 Doctor-Soldier: A SURGEON CAPTAIN IN WARTIME 61 6 Post-Graduate Training: THE EYE DOCTOR 76 7 Marsalforn Sweetheart: LIFE WITH MARIA 87 8 Curing Trachoma: IN GOZO AND IN ASIA 94 9 A First Strike: LEADING THE DOCTORS AGAINST MINTOFF 112 10 Constituency Care: 1962 AND ALL THAT 126 11 The Party Man: ORGANISING A SECRETARIA T 144 12 Minister Tabone: JOBS, STRIKES AND SINS 164 13 In Opposition: RESISTING MINTOFF, REPLACING BORG OLIVIER 195 14 Second Thoughts: FOREIGN POLICY AND THE STALLED E.U. APPLICATION 249 15 President-Ambassador: A FATHER TO THE NATION 273 16 Two Lives: WHAT FUTURE? 297 17 The Sources: A BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE 310 18 A General Index: NAMES AND SUBJECTS 313 'Irridu naslu biex meta nghidu "ahna", ebda persuna ma thossha eskluza minn taht il-kappa ta' dik il-kelma.' Censu Tabone, Diskors fl-Okkaijoni tal-Ftuh tas-Seba' Parlament, 4 April 1992 1 Many faces A FULL LIFE CENSU Tabone is a household name in Malta. -

Election Special Election PN MAJORITIES the SLIMMEST of WINS 159, Labour Avenue, Naxxar Tel: 2388 7939 0088, 2939 49.3% MLP M Altatoday.Co M

election special BaD LOSER pG 5 mIssue 8 • Monday,alta 10 March 2008 • www.tMaltatoday.coodayM.Mt PrICE €0.50 / LM0.21 GONZI WINS WITH THE SLIMMEST OF MAJORITIES PN 49.3% MLP 48.9% MALTATODAY POLLS VINDICATED 159, Labour Avenue, Naxxar Tel: 2388 0088, 7939 2939 paper post News 2 election special | Monday 10 March 2008 news news Monday 10 March 2008 | election special 3 GENERAL GENERAL ELECTIONS 2008 ELECTIONS 2008 – minute for minute – minute for minute SATURDAY – 8 March 10:26 – A tense wait and see. Gonzi wins by narrowest of margins But Labour insiders told MT that 17:51 – Party leaders from all four they expect an 8,000 majority. political parties cast their vote on a Sorting is still under way and quiet voting day where no incidents RAPHAEL VASSALLO of 1966-1971. Although victori- party’s supporters out into the Naxxar. Acknowledging that counting is expected in 45 were reported, and a sense of ous, the PN has ironically also streets in a celebration which the election was too close to call, minutes’ time. A clear indication is business as usual prevailed in most emerged as the biggest individ- proved to be premature. As the Falzon stopped short of actu- expected at midday. Maltese towns and villages. The ual loser from the election, suf- day wore on, samples began to ally conceding defeat, even after tension was however perceptible THE Nationalist Party has won fering a significant drop of 4%: show a trend in favour of a PN Saliba had proclaimed victory. 11:19 – Labour supporters for among political activists of all the 2008 general election with a around 10,800 votes. -

Leadership and Women: the Space Between Us

The University of Sheffield Leadership and Women: the Space between Us. Narrating ‘my-self’ and telling the stories of senior female educational leaders in Malta. Robert Vella A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education. The University of Sheffield Faculty of Social Sciences School of Education October, 2020 ii Life is a journey and it’s about growing and changing and coming to terms with who and what you are and loving who and what you are. Kelly McGillis iii Acknowledgements Thank you for what you did; You didn’t have to do it. I’m glad someone like you Could help me to get through it. I’ll always think of you With a glad and grateful heart; You are very special; I knew it from the start! These few lines by Joanna Fuchs gather my gratitude to many persons who in some way walked with me through this journey. As the phrase goes, “no man is an island”, and surely, I would not have managed without the tremendous help and support of these mentioned below. A special thanks goes to my supervisor Emeritus Professor Pat Sikes. I am tremendous grateful for her sincere guidance, incredible patience, and her full support throughout this journey. I am very grateful for her availability and for her encouragement to explore various paths to inquire into my project. For me Pat was not just a supervisor, she was my mentor, a leader, advisor, and above all a dear friend. Mention must be made also to Professor Cathy Nutbrown and Dr David Hyatt who both offered their advice and help through these years, mostly during the study schools. -

Independence and Freedom

The Last Lap: Independence and Freedom r"$' IThe title of this chapter really says it all: what mattered most in attaining independence was that this ushered in experimental years of internal freedom. Many ex-colonies - too many - obtained independence and became unfit to live in, producing refugees by the thousand. That certainly did not happen in Borg Olivier's Malta.1 By 1969 emigration reached rock bottom, return migration grew, settlers came to Malta from overseas. The economy boomed, creating problems of a different kind in its wake. But these were not so much problems of freedom as of economic well-being and learning to live together and to pull through: there was no repression whatsoever.1 On the contrary the MLP criticism (and a popular joke) was this: tgliajjatx gliax tqajjem il-gvem! Government became rather inconspicuous, unobtrusive, intruding only perhaps by a certain apathy, as well as increasingly a lagging commitment on the part of Borg Olivier's ageing team, especially after 1969. Borg Olivier himself, having attained independence, was no longer at his prime, and his unfortunate private and family foibles did nothing to enhance his delivery. In spite of all that, the election result in 1971 was a very close shave indeed. The Nationalist Party, in government since 1962, did not even have a daily newspaper until 1970, on the eve of the election! By contrast the GWU daily L-Orizzont, started in 1962, and other pro-MLP organs lambasted the Borg 230 Malta's Quest for Independence Olivier administration constantly, and frequently enough, mercilessly. 1970 also saw the use of the GWU strike as a full-scale political weapon when dockyard workers were ordered to strike for months, disrupting the island's major industry mainly on the issue of flexibility. -

Maltese Newsletter 105 December 2015

Maltese Newsletter 105 December 2015 Muscat calls for legally-binding climate change deal at UN summit Prime Minister urges world leaders to 'send a signal of challenges and opportunities of moving towards a climate-friendly future' Tim Diacono www.maltatoday.com.mt/news/ Prime Minister of Malta Joseph Muscat addresses the COP21 summit in Paris Prime Minister Joseph Muscat has urged world leaders to adopt a legally-binding agreement to tackle climate change. Addressing the UN climate change summit in Paris, Muscat cited a joint statement signed during last week’s CHOGM in which the 53 Commonwealth nations agreed to back a legally-binding global climate deal in the form of a protocol. “We hope that such an outcome, according equal importance to mitigation and adaptation, will mobilise all parties in its implementation and put the global community on track towards low-emission and climate-resilient societies and economies,” Muscat said. In the joint statement signed in Malta, the Commonwealth nations also reaffirmed their pledge to mobilise $100 billion per year by 2020 to help developing countries adapt and mitigate to climate change effects. Speaking in his role as the Commonwealth chair-in-office, the Maltese Prime Minister urged “practical and swift action” by governments and all other private and public stakeholders to help out climate vulnerable states and communities. “In this spirit, we have launched the Commonwealth Climate Finance Access Hub, the Commonwealth Green Finance Facility initiative, and the pioneering global Commonwealth Youth Climate Change Network,” he recounted. "Although one of us had reservations on some elements, this remains, I believe, a statement that is worthy of the Commonwealth, a supportive message to all our fellow members of the climate change community and in particular to France." “Our aim here is not just to reach agreement on what governments undertake to do in the years and decades ahead,” Muscat said. -

Form 5 MALTESE HISTORY Unit O Malta' Foreign Policy, 1964-1987

MALTESE HISTORY Unit O Malta’ Foreign Policy , 1964-1987 Form 5 2 Unit O.1.- Malta’s Foreign Policy (1964-1971) Malta’s Coat of Arms 1964-74 Malta-EEC Association Agreement of 1970 1. The Defence Agreement with Britain of 1964. The Defence Agreement was drafted in June 1964 and it contained the following conditions: . Joint consultation between the armed forces of both countries. Only forces of the UK and Malta were to be stationed in Malta. Such forces were permitted to use the harbour, dockyard, airfield, communication facilities. But NATO forces were to be excluded. The treaty was to remain in force for a period of ten years and could be renewed by a new agreement. Borg Olivier’s aim was to increase the involvement of NATO more in Malta. It was agreed that NATO headquarters could continue to operate in Malta after independence. 2. The Financial Agreement with Britain of 1964. The Financial Agreement with Britain consisted of the following clauses: . Britain would assist Malta’s budget and emigration up to a total of £50 million spread over 10 years. 75% of that sum were to be grants and 25% were to be soft loans. £1 million were to be given for the restoration of historical buildings occupied by the British forces. The agreement was considered in Britain as a generous one while Dom Mintoff criticized both agreements for giving too small an aid while at the same time keep considerable control over certain parts of the islands. He also declared that once in power, he would review the agreements to Malta’s advantage. -

The Maltese Gift: Tourist Encounters with the Self and the Other in Later Life

THE MALTESE GIFT: TOURIST ENCOUNTERS WITH THE SELF AND THE OTHER IN LATER LIFE. by MARIE AVELLINO A thesis submitted to London Metropolitan University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2016 1 © Copyright Marie Avellino 2015 All Rights Reserved 2 ABSTRACT This thesis takes a case study approach of the tourist-host encounter in the Maltese Islands, an ex-British Colony and older British tourists (OBTs). OBTs are an important source market for tourism as this is set to grow in volume and propensity. The research investigates how OBTs negotiate identity and memory through their narratives. It does so by examining what is being transacted at a social, cultural and symbolic level between the Maltese and the OBT. It then enquires as to the extent the previous colonial relationship is influencing the present ex-colonial and neo- colonial Anglo-Maltese tourist encounter. The ethnographic study employs a two-pronged strategy. The first interrogates the terms under which spatial and temporal dimensions of the cultural production of the post colony, and the ongoing representations of specific spaces and experiences, are circulated and interpreted by these tourists. The second examines the relationship through the ‘exchange lens’ which is manifested along social and cultural lines within the Maltese tourism landscape context. The research indicates that older adult British visitors have a ‘love’ for the island, which is reciprocated by the Maltese Anglophiles, in spite of some tensions between the two nations in the past. The relationship extends beyond a simple economic transaction but is based on more of a social, symbolic and cultural exchange. -

The Church School Saga (Part 1)

12 13 Feature maltatoday, SUNDAY, 25 APRIL 2010 maltatoday, SUNDAY, 25 APRIL 2010 Feature THE CHURCH SCHOOL SAGA ‘JEW B’XEJN, JEW XEJN’ (PART 1) In the first of a three-part feature, Gerald Fenech TIMELINE delves into the historical importance of church December 1981: The Labour Party wins the 1981 election with a majority of seats but a minority schools in Malta and the battle for their existence of votes. ‘Free education for all’ part of Labour’s in the 1980s that led to the Catholic Church-State manifesto. compromise December 1982: Legal Notice freezing Church School fees at 1982 levels published February 1983: The Holy See protests against the ‘20 points’ awarded to state school students June 1983: Publication of White Paper on Devolution of Church Property Acquired by Prescription July 1983: Archbishop Joseph Mercieca returns from Rome after meetings with Holy See officials. Insists that Church will not cede to government’s demands and will retain all legal rights September 1983: Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici becomes Minister of Education. Curia publishes 1982 accounts, showing losses of Lm190,000, but does not take into account immovable properties not used for ecclesiastical purposes and their The massive demonstration in support of Church schools Dingli Street, Sliema, 1984 income. PRIVATE education has always been a contentious issue er draconian measures, such as the freezing of compensa- October 1983: Church files case in Constitutional in Malta. In the eyes of some, it’s a sector that has been tion limits up to a maximum of Lm50,000 (€120,000) and Court to declare Devolution Act null. -

HMS Olympus: a Tale of Tragedy and Heroics

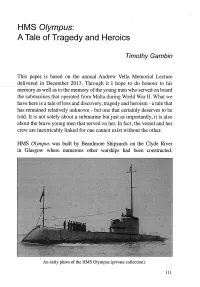

HMS Olympus: A Tale of Tragedy and Heroics Timothy Gambin This paper is based on the annual Andrew Vella Memorial Lecture delivered in December 2013. Through it I hope to do honour to his memory as well as to the memory of the young men who served on board the submarines that operated from Malta during World War n. What we have here is a tale of loss and discovery, tragedy and heroism - a tale that has remained relatively unknown - but one that certainly deserves to be told. It is not solely about a submarine but just as importantly, it is also about the brave young men that served on her. In fact, the vessel and her crew are inextricably linked for one cannot exist without the other. HMS Olympus was built by Beardmore Shipyards on the Clyde River in Glasgow where numerous other warships had been constructed. An early photo of the HMS Olympus (private collection). III STORJA2015 The Olympus was down in 1927, launched in 1928 and subsequently commissioned in 1930. She was part of the 0 or Odin Class submarine, the first submarine to be designed and built after World War One.l This class of submarine measured 84 meters in length and nine meters at the beam. It had a displacement of 1700 tons on the surface and 2030 tons submerged. Of the six vessels in this class built for the Royal Navy, one, the Odin was built at Chatham.For the record, HMS Odin was lost off Taranto with all hands on deck in 1940.2 The other boats were built to moderately differehtspeCifications - two were for the Australian Navy and three destined to the Chilean Navy. -

Malta: Euroscepticism in a Polarised Polity Roderick Pace

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by OAR@UM South European Society and Politics Vol. 16, No. 1, March 2011, pp. 133–157 Malta: Euroscepticism in a Polarised Polity Roderick Pace From the candidate country in the EU’s 2004 Enlargement with the lowest levels of support for EU membership, the situation in Malta has changed since accession so that all mainstream political parties now support membership. After presenting factors influencing attitudes to Europe, the article analyses party euroscepticism from Maltese independence in 1964 to the present, focusing on the Malta Labour Party. The examination of public opinion focuses on the period before and after the 2003 referendum on EU membership. The significant role of the eurosceptic media is also noted. Keywords: European Integration; Political Parties; Party Euroscepticism; Public Opinion; Mass Attitudes; Malta Labour Party For many years, EU membership encountered fairly strong opposition in Malta and up to the last moment it hung in the balance. The Nationalist Party (Partit Nazzjonalista—NP) and the Malta Labour Party (Partit Laburista—MLP),1 the only political parties represented in the Maltese House of Representatives, each commanding the support of approximately half of the Maltese electorate, took diametrically opposed positions. The NP promoted EU membership, the MLP Downloaded by [University of Malta] at 07:54 01 October 2014 opposed it. In 2003 the Maltese electorate twice voted in favour of membership by a narrow margin, first in a referendum and then in a ‘cliff hanger’ general election, called because the MLP refused to accept the referendum outcome (Cini 2003) (Tables 1 and 2).